The origins of Christian Easter

The period between the 1st and 4th centuries AD saw one of the most important transformations in history; the rise of a small underground religious movement called Christianity to become the dominant religion of Europe and the Western world.

The Christian legacy of the Roman Empire survives today as the religion remains central to our culture as can be seen in the celebration of religious holidays such as Easter.

Two moments that greatly defined the Empire’s relationship with Christianity were the execution of Jesus of Nazareth on the orders of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate and the legalisation of Christianity by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great.

These events are completely contrasting and separated by almost three centuries of history during which time the role of the Roman Emperor evolved radically from occasional persecutor of the Christian faith to eventually patron of the very same religion.

That the site of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ in the 1st century AD had become by the 4th century AD a preeminent destination for Christian Roman pilgrims demonstrates the religious and cultural shifts with the Empire over these centuries.

Both Pontius Pilate and Constantine the Great played important roles in the development of Christianity in the Roman Empire between the 1st and the 4th centuries AD.

Who was Pontius Pilate?

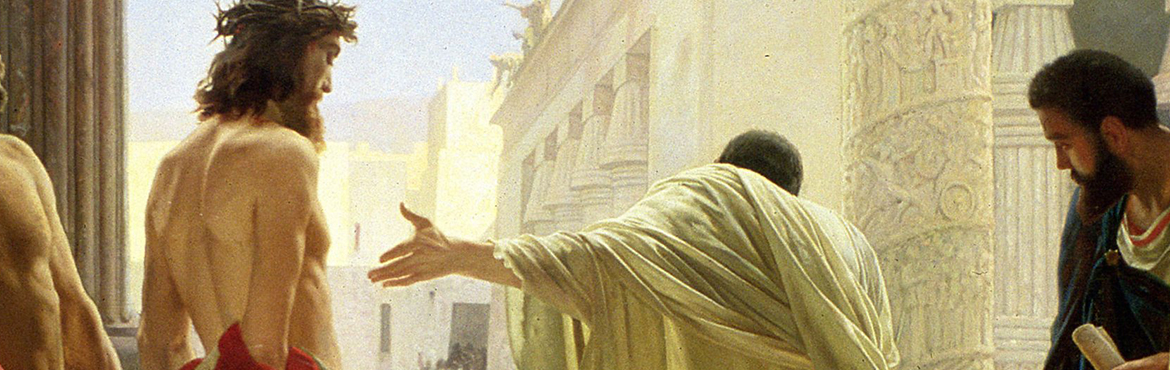

Pontius’ Pilate was, of course, the man who convicted Jesus Christ and sentenced him to be executed by crucifixion at some point between AD 30 and 33.

As the prefect of Judaea from AD 26 to 36, Pilate was charged with maintaining law and order in his province during the reign of the Emperor Tiberius.Contemporary evidence of Pilate can be seen in a number of coins minted in the years AD 29-31 as well as in the inscribed stone bearing his name and title found in Caesarea Maritima, Israel.

Although Christ’s crucifixion by Pilate is confirmed by a number of ancient sources, there is still great deal of mystery surrounding the man, especially with regard to his life following this famous episode.

Kevin Butcher is Professor of Roman history at the University of Warwick and author of The Further Adventures of Pontius Pilate. For him Pilate was “one of the Roman Empire’s most infamous characters” and it is interesting to find that two contrasting representations of Pilate emerge from ancient sources.

The tradition of the ‘good’ Pilate presents a weak and indecisive official but one who ultimately recognized Jesus’ innocence and attempted to save him from execution.

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and the apocryphal Gospel of Peter are all determined to diminish Pilate’s responsibility, or to exonerate him, or even to portray him as “a believer”, and this is exemplified by the recognisable image of the governor washing his hands to absolve himself of the crime.

Later writers like Tertullian and Saint Augustine even hailed Pilate as a Christian convert and a prophet. (Tertullian, Apology, 21; Augustine, Sermon 201.2)

Professor Butcher accounts for these positive portrayals by explaining that in the early years of Christianity “it would have been dangerous to accuse an imperial official of deicide” and instead it would have been prudent to pacify the Roman Empire.

He also points out that there was a strange fascination with the figure of Pontius Pilate amongst early Christians, with “the image of the guiltless governor, the chief witness of the Passion, becoming an important theme in early Christian writings”.

1st century AD Jewish writers Philo of Alexandria and Flavius Josephus paint a much darker portrait of Pilate. Philo describes the governor as a “man of an inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition” and adds that his administration was marked by many injustices. (Philo, Embassy to Gaius, 301–2) For Josephus he was an enemy of the Jewish nation. (Josephus, The Jewish War, 2.169-77).

In a 4th century AD work, Eusebius’ Church History, Pilate meets a humiliating end - after falling into misfortunes in Rome he commits suicide. (Eusebius, Church History, 2.7) So the real man remains an enigma and in Professor Butcher’s view “a shadowy metaphor for opposites: equivocation and stubbornness, cowardice and heroism, cruelty and clemency”.

So what happened to Pilate?

Josephus provides the last reliable statement on Pilate’s activities, recounting that in late AD 36 he had been recalled from Judaea to Rome following his alleged mishandling of a riot involving the Samaritans. (Josephus, The Jewish War, 18.85-89). He would have expected to face a hearing before the Emperor however before his arrival, Tiberius died and Pilate disappears from all records. However brief his time in the limelight, his actions secured an enduring legacy. He set in motion Jesus’ execution, one of the central narratives in Christianity, which raised Jesus to the status of martyr and fulfilled messianic prophecies.

In Pilate’s judgement and conviction of the religious leader we can see the first confrontation between the Roman Empire and a new religious sect in a public demonstration of imperial authority over dissenters.

Persecution

During the following centuries Christians endured sporadic persecution in the Roman Empire.

The first great persecution was carried out during the reign of the Emperor Nero, who used them as a scapegoat for the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64.

Persecution intensified during the 3rd century AD, as Christianity spread and the Roman Empire entered a period of crisis. Catastrophes afflicting the empire were once again blamed on Christianity.

Under the reign of the Emperor Decius in AD 250 Christians were again targeted. Decius ordered every inhabitant of the Empire to take an oath to the Emperor and make a sacrifice to the Roman gods before officials. Many Christians refused to comply and were tortured or killed as a result.

The worst period for Christians began in AD 303 under the Emperor Diocletian whose attempts to eradicate Christianity from the Empire led to the destruction of churches and Scriptures, and the imprisonment and slaughter of many.

Christians who were executed during the later empire became martyrs and many were canonised:- two of the most notable being Saint Sebastian, commonly depicted tied to a post or tree and shot with arrows, and Saint Valentine of Rome who is commemorated on 14th February.

Turning Point

The great turning point for Christianity came with the rise of Constantine the Great, who ruled as emperor in the early 4th century AD. He is renowned for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and legalise the religion, liberating thousands throughout the Empire.

He ascribed many of his victories to his conversion and the support of the Christian God. One such example is his success at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge against the forces of his rival Maxentius in AD 312. The night before battle, Constantine supposedly experienced a divine vision in which he received instructions to paint the Christian symbol of the Chi Rho on his soldiers' shields to ensure his triumph.

After being named Roman Emperor in the West, he issued the Edict of Milan in AD 313 which permanently established religious toleration for Christianity and returned all property confiscated from the Church during previous persecutions.

Constantine set a precedent for the position of the Emperor within the Church which would be adopted by later European rulers. The State became the protector of the Church, and the emperor the principal sponsor of Christianity.

Constantinople

By AD 324, Constantine had reunited the two halves of the Roman Empire under his rule and decided to establish Constantinople as the new capital, dedicating the city to the Christian god.

He set a standard by using the state’s resources to build some of Christendom’s most important churches, inspiring later Christian rulers to replicate similar projects. Constantine and his mother Helena were responsible for the construction of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, at the supposed location of Jesus' crucifixion and tomb which became the holiest place in Christendom.

Christians were able to claim Jerusalem and its holy places and promote the city as the ultimate goal of Roman pilgrimage.

The eventual alliance between Church and Empire facilitated the growth of the Church with Christians using their newfound freedom to worship publicly and establish missions, leading to the conversion of millions. It also strengthened the legitimacy of the imperial rule as emperors could be styled as God’s chosen ruler and could even canonised, as happened to Constantine and his mother Helena. (Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 1.24)

So despite intermittent attempts by the Roman Empire to supress the religion through persecution, it failed to slow down the Christianisation of Roman society. The rise of Christianity in the empire represented not only a break with the dominant values of the Greco-Roman world but ultimately altered the trajectory of world history.

Published

26 June 2018

Kevin Butcher is a professor of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick and author of The Further Adventures of Pontius Pilate, a historical novel available in paperback and as an e-book. Professor Kevin Butcher received his PhD from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, in the field of Roman numismatics. He is also the author of Roman Syria: And the Near East (J. Paul Getty Trust Publications, 2004). He joined Warwick in 2007, after a term as a Getty Visiting Scholar in Los Angeles, California.

Kevin Butcher is a professor of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick and author of The Further Adventures of Pontius Pilate, a historical novel available in paperback and as an e-book. Professor Kevin Butcher received his PhD from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, in the field of Roman numismatics. He is also the author of Roman Syria: And the Near East (J. Paul Getty Trust Publications, 2004). He joined Warwick in 2007, after a term as a Getty Visiting Scholar in Los Angeles, California.

Terms for republishing

The text in this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Share