2024

Reinventing Rome's Forgotten Past - the lost significance of the Lacus Curtius by Chris Parr (July 2024)

No trip to Rome is complete without a visit to the Forum Romanum, once the commercial and cultural heart of the ancient city. Amidst the imposing marble columns which testify to Rome’s past glory, a rather unassuming site is often overlooked by visitors and experts alike. Here, the Lacus Curtius (literally translated as "Curtius’ pool"), a trapezoidal area of shabby-looking travertine pavement with the remains of a round structure (Fig.1) acts as a reminder to Rome’s forgotten past. Not even the ancient Romans could be sure about its significance, so what exactly was the reason for the Lacus Curtius’ existence? Who was the 'Curtius' who gave their name to the monument? And why should we care about someone or something which the ancient Romans themselves had very little idea about?

Fig. 1. The round section of the site of the Lacus Curtius as visible to modern visitors to the Forum Romanum, Rome. The ancient remains of the travertine pavement have been covered by a modern roof to protect from weather damage. (Image: author's own photograph, April 2023).

The visible remains have been dated to the end of the first century BC, when the Forum Romanum was repaved by Augustus. Beneath this layer are two older phases of the monument, the oldest dating to around 184 BC, and the other attributed to the time of Sulla in the early first century BC. The two earlier phases of the monument (Fig. 2) retain traces of rectangular bases, surely the ‘dry altars’ (aras siccas) of the Lacus Curtius referenced by Ovid (Fasti 6.403-4), which would suggest some religious or spiritual significance of the site. Present across the three phases of the monument is a circular structure which has been identified as a well, surely the lacus (pool) to which the site’s name refers. Modern visitors to the site can see a replica of the relief originally from the late first century BC which accompanied the Lacus Curtius to explain its significance (Fig. 3). The relief depicts an armed knight on horseback in what appears to be a marshy area, but it is not clear exactly who this knight is supposed to be or what he is doing, leaving ambiguity as to what the story behind the monument was and revealing the Romans own uncertainty over the site’s origins.

Fig. 2: Overlaid plans of the first two phases of the Lacus Curtius. Note the differences in configuration and overall area of the complex. First phase indicated by areas with scored markings, second phase by areas with no markings. (Image: Giuliani (1987) 107.).

Fig. 3. Musei Capitolini, Rome, Inv. NCE 2905. Relief depicting one of the myths associated with the Lacus Curtius. A copy of the relief has been placed next to the site in the Forum Romanum, as has been suggested was the case in antiquity. (Image: author's own photograph).

Literary accounts of the monument's origin

By the first century BC, even the Roman author and polymath Varro, widely regarded as Rome’s greatest scholar, could not discern exactly what the Lacus Curtius complex commemorated. Instead, Varro presented three explanations for the monument, each recorded by historians before him (Varro, De Lingua Latina 5.148-50). The first of these, extant only in Varro’s account, claims that the Lacus Curtius marked a spot struck by lightning that was fenced off by order of the Senate during the consulship of C. Curtius in 445 BC, and so the monument was named after the presiding Consul. Modern historians have questioned whether this could have been the case because the consulship was only available to the ultra-elite patrician families, while the Curtius family was only of plebeian status and, therefore, ineligible to run for Rome’s highest political honour at that time. Additionally, other sources seem confused over the names of the consul for 445 BC, sometimes calling him Curiatius instead of Curtius, and occasionally adding the cognomen (last name) Chilo or Philo (Livy, History of R|ome 4.1.1 and 7.3; Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 12.31.1). Historians following Varro favoured other explanations for the Lacus Curtius, and so this version subsequently fell out of use.

The second account records the story of a young Roman equestrian named Marcus Curtius. The legend explains that a chasm opened in the Forum Romanum in 362 BC and the haruspices, Roman priests who determined the mood of the gods, proclaimed that the bravest citizen must be sent down into the crevasse to shut it. The young Curtius armed himself, mounted his horse, and plunged into the chasm, which then promptly closed. Livy’s version of the tale, in which the haruspices demanded that the Romans cast into the chasm the greatest strength of the Roman people, set the tone for later authors, such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Valerius Maximus, Pliny the Elder, Cassius Dio, and Festus, to use this as a story of great patriotism (Livy, History of Rome 7. 6; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 14. 11; Valerius Maximus, Memorable Sayings and Doings 5. 6. 2; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 15. 78; Dio Cassius, Roman History 7.30.1-2 = Zonaras 7.25; Festus 42L). This story also appears to be the origin of the tradition recorded by Suetonius (Life of Augustus 57.1), whereby visitors to the Lacus Curtius would toss a small coin into the well to pray for the Emperor’s health, just as nowadays we might empty our small change into a wishing well in the hope of good fortune.

The third tradition of the story places the Lacus Curtius’ origins at the time of Romulus’ war with Titus Tatius, leader of the neighbouring Sabines. According to this version, Mettius Curtius, a Sabine warrior, managed to escape Romulus and his men by hiding in a swampy spot, later commemorated by the Lacus Curtius (Varro, De Lingua Latina, 5.149). Whilst Varro gave a fairly favourable portrayal of the ‘very brave’ Mettius Curtius, possibly due to his own Sabine origins, the portrait of Mettius Curtius given by other authors became increasingly harsh over time (Livy, The History of Rome 1.12-3; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 2.42). This culminates in Plutarch’s version, in which Mettius Curtius, consumed by arrogance, rashly rode his horse into the marsh where the Forum would later develop, became stuck, and abandoned his horse to save himself (Plutarch, Lives, Romulus 18).

Receptions of the Lacus Curtius in contemporary Roman history

It is truly remarkable how few details these accounts agree on. The only features constant across all three versions are that a man called Curtius was involved in something that happened on a particular spot in the Forum Romanum. There is no sense of an approximate time at which the event occurred, with dating ranging nearly four centuries from just after Romulus’ foundation of Rome in 753 BC to the alleged opening of a chasm in the Forum Romanum in 362 BC. Later, the carved relief which accompanied the site also left a degree of ambiguity: by the time of the relief’s production at the end of the first century BC, both prominent Curtius stories featured the protagonist on horseback in his armour, whilst elements of both stories appear to be present (the marshy appearance of the ground from the Mettius Curtius version contrasts with the apparent downward trajectory of the rider and his horse from the Marcus Curtius version), so either version could be depicted.

In reality, it seems not to have mattered to the Romans of the later first century BC and thereafter what the original significance of the Lacus Curtius was. There did not need to be one ‘true’ story for why the monument existed; what mattered was that it did exist to remind them of the stories they had heard about the heroic Roman Curtius in tandem with those of the arrogant Sabine Curtius. Furthermore, by comparing the development of these two versions of the myth, we can see that they grew in dialogue with each other: as the Roman people presented themselves as the city’s most important resource, outsiders were characterised as arrogant and no match for Rome’s brave warriors, clearly demonstrating the Romans’ superiority. Logically, it was not possible that both stories could be the true reason for why the monument was constructed, but they existed in harmony because the values to which they spoke were culturally significant to the Roman people.

A later episode of the Lacus Curtius’ history can help us see this development in action. In the tumultuous AD 69, known as The Year of the Four Emperors, the Emperor Galba, facing his final hours, fled to the Forum Romanum. Tacitus (The Histories 1.41) records that Galba was thrown from his litter at the site of the Lacus Curtius, accepted his fate, and offered his life ‘if the good of the state demands it’ (si ita e re publica videretur). The echoes of both traditions ring out at this point. The parallels with the heroic sacrifice of Marcus Curtius are apparent: a Roman gives their own life for the benefit of the Roman state. Through this parallel with Marcus Curtius, Galba is portrayed as acting selflessly to save Rome. However, there are also links to the Mettius Curtius story: both Galba and Curtius faced certain doom at the hands of their enemies at that location. This comparison equates Galba with an enemy of Rome, and we can see parallels between the Sabine War, which involved neighbouring Italian states, and the civil war which followed Galba’s death, presenting a more pessimistic view of Galba and his legacy. Tacitus presents Galba’s death in relation to both traditions, each providing a different outlook on Galba’s legacy, demonstrating that both versions of the Curtius myth survived in their own right and could exist together.

With this in mind, we can see the complex relationship between material culture and an oral tradition. The static, physical monument, whose very existence acts as a reminder of an event from the past, is unable to preserve a specific version of the origins of the Lacus Curtius, and even those for which we have evidence vary in their character. Whilst a physical object can prompt us to remember, memory exists in the minds of individuals, verbally shared between people and constantly changing form as it is recounted by every person in their own way. Each recollection of a memory is reshaped by the individual who remembers, unconsciously influenced by the values of the time, until the memory takes on noticeably different features and eventually becomes unrecognisable. Additionally, a monument’s significance is constantly evolving due to the events which occur at a particular place taking on qualities of the stories associated with the monument. Memories evolve and can be added to, becoming reflections of more current attitudes and ideas. In this way, the physical monument, whilst not changing its form in any way, gains new significance through the development of the memories attached to it.

Whilst we may never know the original significance of the Lacus Curtius, the monument’s later significance became valuable in its own right through its relation to ideas prevalent at different times in Roman history. As historians, it can be tempting to focus in on one particular moment of the site’s history and attempt to understand why the monument was constructed in the first place. To do so would be to misunderstand the role of monuments in culture, viewing them as fixed reminders of past events. Instead, the Lacus Curtius was significant for the stories attached to it and the meanings which people drew from the site, continually reimagined in the light of contemporary events and values. Although the original meaning of the Lacus Curtius has been lost to the sands of time, the constant evolution and reinvention of the monument’s significance renders this irrelevant at later points in the site’s history. The Lacus Curtius may have origins shrouded in mystery, but the monument survived through the constant development of its significance to align with contemporary values.

BibliographyPrimary Sources:Dio Cassius, Roman History, Vol. I: Books 1-11, trans. E. Cary, H. B. Foster (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914).

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Vol. IV: Books 9-12.40, trans. C.H. Oldfather (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1946).

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Vol. I: Books 1-2, trans. E. Cary (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1937).

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, Vol. VII: Books 11-20, trans. E. Cary (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950).

Festus, De Verborum Significatu Quae Supersunt Cum Pauli Epitome, ed. W. M. Linsay (Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner, 1913).

Livy, History of Rome, Vol. I: Books 1-2, trans. B. O. Foster (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919); Volume II: Books 3-4, trans. B. O. Foster. L(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1922); Volume III: Books 5-7, trans. B. O. Foster (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924).

Ovid, Fasti, trans. A. Wiseman and T.P. Wiseman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Plautus, Comoediae, Vol. 1: Amphitruo; Mercator, ed. W. M. Lindsay (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1903).

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Vol. IV: Books 12-16, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1945).

Plutarch, Lives, Vol. I: Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola, trans. B. Perrin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914).

Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, trans. C. Edwards (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Tacitus, The Histories, trans. W. H. Fyfe and D. S. Levene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Doings and Sayings, Vol. I: Books 1-5, trans. D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Varro, On the Latin Language, Vol. I: Books 5-7, trans. R. G. Kent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938).

Secondary Sources:Broughton, T. R. S. (1951) The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, Volume 1: 509 B.C. — 100 B.C (New York: American Philological Association).

Claridge, A. (1998, 2nd edn.) Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Coarelli, F. (1983) Il foro romano Vol. 1: periodo arcaico (Rome: Quasar).

Coarelli, F. (1985) Il foro romano Vol. II: periodo repubblicano e augusteo (Rome: Quasar).

Giuliani, C. F. (1987) L’area centrale del Foro Romano (Florence: S. Olschki).

Giuliani, C. F. (1996) ‘Lacus Curtius’ in E. M. Steinby (ed.) Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, vol. 3: H-O (Rome: Quasar) 166-67.

Grant, M. (1971) Roman Myths (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson).

Platner, S.B. and Ashby, T. (1929) A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press).

Poucet, J. (1967) Recherches sur la légende sabine des origines de Rome (Kinshasa: Bureaux du Recueil, Bibliothèque de l'Université Louvain; Éditions de l'Université Lovanium.

Richardson, L. (1992) A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Johns Hopkins University Press).

This article was written by Chris Parr, who completed an MA in the Visual and Material Culture of Ancient Rome last year. During the course, he developed an interest in the relationship between material culture and memory, which culminated in his MA dissertation, entitled 'Forgetting in the Forum: The Loss and Creation of Memory in the Forum Romanum'. Chris will return to the University of Warwick in October to study towards a PhD in Classics and Ancient History.

Practical and Stylish- Gladiatorial Armour as Costume by Tallulah George (June 2024)

The image of a gladiator in the modern mind, owing to screen adaptations and legends, is one of a fearsome, blood-thirsty, killing machine, a pawn, with no rights or personal identity. Though undoubtedly a dangerous lifestyle, a re-examination of material, focused on the evidence closer to the subjects themselves, clearly demonstrates that gladiators were risking their lives, but not necessarily to the degree usually implied. In fact, gladiators might in some ways be imagined as something akin to actors, with whom they were inextricably linked through their shared social standing of 'infames' (non-citizens, social outcasts with no legal rights), but the similarities in role are more pronounced when the armour found in Pompeii is analysed sufficiently.

A large amount of gladiatorial armour and weapons were discovered in the exedra in the middle of the east end of the Quadriporticus at Pompeii (VIII.7.16), including helmets, greaves, armguards and retarii shoulder pieces (Figures 1-3). These finds allow examination of the materials, construction techniques and decoration. In fact the majority of the armour pieces are intricately decorated, with scenes of myth, society, and nature, with every element forming the costume.

Figure 1: Left and right side of a murmillo helmet, intricately decorated with scenes from book two of the Aeneid. The is the most ornate and heaviest of all known gladiator helmets at 4.5kg. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5673. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 99-100. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

Figure 2: Leg guard belonging to a thraex or hoplomachus, decorated with the image of Jupiter tonans, leaning on a lance with his left arm and holding a bundle of thunder bolts in his right. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5645. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 68. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

Figure 3: Galerus (retarius shoulder guard) decorated in relief with a rudder, an anchor, a crab, and a trident with a dolphin which are considered attributes of the sea-god, Neptune. The retiarius’ distinctive weapons of a net and trident evoked a fisherman thus these marine motifs are appropriate. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5639. (Image: Jacobelli (2003) Figure 10.)

Despite gladiators taking an oath (Sacramentum Gladiatorum) where they agreed to be burned, bound, beaten, and killed, they had more purpose than simply sacrificing themselves. They were Romans, doing their job, fulfilling their duties of putting on a show. They acted as vehicles of communication, embodying and projecting Roman values, such as military prowess and strength, fighting and dying willingly. Gladiators were more than murderous outcasts; they were fundamental to Roman society; they were performers and acted as human indoctrination devices.

The Roman amphitheatre was the grandiose stage for public representation of power and wealth, a place for spectacle and the witnessing of Roman dominance. Nearly every major theme of the Roman power structure was deployed in the spectacles: social stratification, political theatre, punishment and justice, civilization and empire versus barbarianism and the ‘other’, and the exaltation of masculinity. The armour and its messages bridged the gap between the gladiator and wider society and added to the characterisation of each individual fighter, cementing them as actors in costume, and conveying Roman values.

Some motifs and imagery have simple meanings and their appearance is logical, for example: the distinguishing griffin demarcating the Thracian helmet acted as a protector from evil, instilling strength, military courage and leadership (Figure 4.1);Medusa’s head, often figuring centrally, was intended to ward off evil and serve as a symbol of justice (Figure 4.2); Hercules and his characteristic associations such as club and lion skin, suggested the incredible feats the gladiators are undertaking and their astonishing success (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.1: Helmet of a Thracian gladiator, adorned with the characteristic griffin crest. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5649. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 38. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

Figure 4.2: Helmet of a Thracian gladiator, decorated with the head of Medusa in centre. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5650. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 51. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

Figure 4.3: Detail of a murmillo helmet. A herm of Hercules decorates the front-facing end of the crest. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5672. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 127. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

A modern mind may overlook the flamboyance and pomp of gladiatorial games, and rather focuses on their sordid nature, nevertheless, there was a central pageantry framing the bloody entertainment at the arena. The armour was a costume worn to depict a frightening fighting machine but also acted as a prop in the artistic expression of ideology and communication of messages. Gladiators presented publicly as a standardised mob, their visored helmets, worn by all but the retiarius, removing individuality and encouraging emotional detachment from the man during combat. The helmets effectively anonymised and dehumanised the combatant whilst protecting the head and face from injuries. This further suggests the men were actors, doing their job, whilst designed to fight, suffer, and bleed, albeit not in a way serious enough for them to necessarily die. The murmillo, for example, was the most heavily armoured gladiator, with the armour weighing up to 18kg, upholding the image of a man designed to fight and withstand blows, while providing an extensive canvas for intricate symbols and imagery. The gladiators were meant to look imposing, so despite the immense weight of this armour seeming impractical, it was a fundamental aspect of forming the gladiator. They wear this armour and alter their identity: no longer the subjugated Roman man, they are the 'great gladiator'.

Due to the ornamental nature of the majority of the armour found at Pompeii, many scholars, noting the detail and intricate artwork, believe these pieces were not worn in combat and were only worn during the procession, pompa, before gladiatorial contests began or perhaps given as prizes. Yet despite the limitations the armour imposed, being heavy, impractical, and restricting manoeuvrability, I believe that it was still worn for protection during combats, forming their costume in the arena.

This theory primarily rests on two facts. The first is that no elaborate helmets for the secutor, who was the usual opponent for the net-wielding retiarius, have been found. The secutor wore a smoother, rounded, more streamlined helmet so that the retiarius’ net does not get caught and rather, slides straight off (Figure 5). If this elaborate armour was just parade wear, the secutor would have had an ornate parade helmet like every other type of gladiator, in addition to the plain combat helmet.. The second finding that compounds the theory that the elaborate helmets were worn in combat is the existence of a patched helmet of a provocator (Figures 6a & 6b). The helmet was patched in ancient times suggesting a blow to the head, and furthermore, the patch itself has signs of damage suggesting further impact to the helmet. This strengthens the argument that armour was a costume and the gladiators were playing a role.

Figure 5: Helmet of a secutor, lacking embossing. There are two small, round openings for vision and a lack of breathing holes. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5643. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 211. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

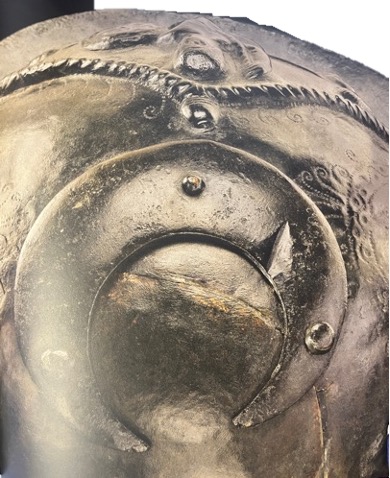

Figure 6a: Detail of the right side of a helmet of a provocator. The plume socket is framed by engraved motifs. The helmet has been repaired in ancient times by a crescent-shaped patch that was attached by three rivets. The mark of a blow makes clear the helmet was used again in combat after the first repair. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5657. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 191. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

Figure 6b: Detail of the crescent-shaped repair on the right side of a helmet of a provocator, with a mark of a blow following the repair. 1st century CE. New Barracks, Pompeii. MANN Inv. 5657. (Image: Mellor, Dozio & Eckert (2013) 193. Photograph by J. Lipták.)

The extensive work, time and expense in creating these pieces illustrates gladiators as valuable commodities, worthy of investment, and a pride surrounding their appearance. If a piece of armour was occasionally damaged, it not only would have been easy to repair, the armouries being close to the ludus (gladiatorial training school), but it would have been a minimal expense compared to the games in general. Gladiatorial injury and death would cost a lot more than the repair of equipment. In fact, the danger to a gladiator imight have been even less than it appeared; embossed armour was actually stronger than a piece with a smooth surface, as the decoration thickens and stabilises the metal. When compared with military armour, the bowl of Pompeiian gladiatorial helmets have an average thickness of around 1.5mm, with the visor gratings averaging 1.8mm and all edges faced with metal up to four times thicker than the bowl. By contrast, military helmets of the same period are not decorated and have an average thickness of 1mm, suggesting gladiators had to be better protected for harder and more consistent blows in close contact to their head. Admittedly, the armour found at Pompeii is in very good condition. Experiments have shown that the bowls of replica helmets, with the same thickness as the originals would suffer slight, barely perceptible denting even when struck with a direct blow, with the exception of a blow from a trident. Weaponry was also adapted: swords were light and short and could only injure unprotected parts of the body. Another counter point to this armour being worn solely for parades is that though the weight is very high, weighing a lot more than military armour, they would have to wear it infrequently for a short period of time in the arena, whereas military men would have had to wear their armour for hours, fighting and marching.

Like the games themselves, armour was both practical and stylised. This elaborate armour was not just worn in parades but in the arena as well: it was worn to protect but also to communicate. The decorated armour was essential for the concept of the gladiators as it not only added to the appearance of each individual combatant but also to the glory and wealth of the games, and thus Rome, with extravagance at the heart of the concept. The armour also cements the position of the gladiators as actors playing a part not only in the arena when they performed, but in Roman society as a whole communicating values, messages, and ideals through art. The difference between gladiators and actors, however, is that actors were seen as the inversion of the soldier-citizen, and the antithesis of ‘Romanhood’, whereas gladiators embodied Roman masculine virtues, relating to courage and strength. Though actors were also celebrities patronised by the emperors, theatres were still sites of social tension where political authorities were challenged, whereas amphitheatres were places where political officials could enforce their authority, their autonomy, and their power, with armour being a useful tool of transmission. The Roman public disgraced the artist, in this case the gladiator, but glorified the art (Tert. De spect. 22: artem magnificant, artificem notant), their performances for the masses. This armour was imperative in the presentation of the gladiator to the public.

The analogy of gladiators as actors was fundamental in conveying the ability to adopt the mask, their role extending beyond 'fighter' or 'killer'. The armour exposes the gladiator as more than a legend, an inhumane destructive force, but also as an individual, playing their given or chosen role in ancient society. This material bridges the gap between the observed spectacle and the lived experience, exposing the man beneath the helmet, integrating humanity and history

BibliographyPrimary Sources:

Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, trans. C. D. Yonge, (Harper and Brothers, 1877) from Attalus – https://www.attalus.org/cicero/tusc2.html, last accessed 03/09/23.

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, trans. J. Bostock (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855).

Tertullian, On the Spectacles, trans. T. R. Glover, G. H. Rendall (Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. T Hobbes (London: Bohn, 1843).

Secondary Sources:

Balsdon, J. P. V. D. (1969). Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome, (London: The Bodley Head ltd).

Beard, M. (2008). Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, (Suffolk: Profile Books Ltd).

Burliga, B. (2016). ‘Tertullian on the paradox of the Roman amphitheatre games: "De spectaculis" 22’, Vox Patrum 65:119–127.

Cadario, M. (2014). “Iconography of the Roman World” in Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology 9, ed. C. Smith, (Springer: Springer Cham), 3659-3672.

Carter, M. J. (2006). ‘Gladiatorial Combat: The Rules of Engagement’, The Classical Journal, 102.2: 97–114.

Connolly, P. (2003). Colosseum: Rome’s Arena of Death, (London: BBC Books).

Coulston, J. C. N. (1998). ‘Gladiators and soldiers: personnel and equipment in ludus and castra’, Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies, 9:1-17.

Dunkle, R. (2013). Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome, (Oxfordshire: Routledge).

Edmondson, J. (1996). “Dynamic Arenas: Gladiatorial Presentations in the City of Rome and the Construction of Roman Society during the Early Empire” in Roman Theatre and Society, ed. W. J. Slater, (Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press), 69-112.

Edwards, C. (1993). The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Edwards, C. (1997). “Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome”, in Roman Sexualities, eds. J. P. Hallet & M. B. Skinner, (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 66-95.

Fagan, G. G. (2011). The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Fagan, G. G. (2015). "Training Gladiators: Life in the Ludus", in Aspects of Ancient Institutions and Geography, eds. L. L. Brice & D. Slootjes, (Leiden: Brill), 122-144.

Futrell, A. (1997). Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power, (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Gell, W. & Gandy, J. P. (1852). Pompeiana: The topography, edifices, and ornaments of Pompeii, (London: H.G. Bohn).

Grant, M. (1967). Gladiators, (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson).

Gunderson, E. (1996). ‘The Ideology of the Arena’, Classical Antiquity, 15.1: 113–151.

Handelman, D. (1990). Models and Mirrors: Towards an Anthropology of Public Events, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Jacobelli, L. (2003). Gladiators at Pompeii, (California: Getty Publications).

Junkelmann, M. (2000a). Gladiatoren: Das Spiel mit dem Tod, (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern).

Kyle, D. G. (1998). Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. (London: Routledge).

Meller, H., Dozio, E., Eckert, K. & Lipták, J. (2013). Gladiator: Taglich den Tod vor Augen, (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern).

Stevens, J. A. (2014). Staring into the Face of Roman Power: Resistance and Assimilation from behind the ‘Mask of Infamia’, (California: University of California; Dissertation and Theses Global).

Ville, G. (1981). La Gladiature en Occident: Des origines à la mort de Domitien, (Rome: Ecole française de Rome).

Wiedemann, T. (1992). Emperors and Gladiators, (London: Routledge).

Wistrand, M.(1992). Entertainment and Violence in Ancient Rome: The Attitudes of Roman Writers of the First Century A.D, (Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis).

This article was written by Tallulah George, who completed her MA in the Visual and Material Culture of Ancient Rome at Warwick last year where she focused on art, self-representation and sociological interpretations. Her MA dissertation explored understudied Pompeian gladiatorial material, namely armour and graffiti, comprehending gladiatorial identity and self-presentation. Tallulah is passionate about making classics relevant to wider audiences and making it relatable to the modern day, check out her website to see how she does this: https://classicsbytallulah.co.uk

From puzzling images to a puzzle of images: a red-figure thread from Peucetia by Carlo Lualdi (May 2024)

Red-figure vases, though seemingly showing repetitive patterns and designs, nevertheless reveal rich details and narratives, offering insights into ancient cultures. Indeed, the decoration of these vessels can be analysed as part of a group of ‘speaking objects’, part of a ‘figural speech’, where the images on these objects can be seen as being specially selected to convey specific messages and concepts.

A notable case study linked to this topic is a group of red-figure vessels from Greece and Southern Italy, found in a tomb near Gravina di Puglia, dating to the end of the fifth century BCE and known as 'tomb 2/1994' (for more details on the tomb see Cianco 1997, and on the vases specifically, see Todisco 2018). This assemblage can deepen our understanding of ancient mindsets and the traditions linked to the Peucetians, the Italic people who inhabited the central part of the modern Puglia region in the southeastern part of the Italian peninsula.

The grave goods found in this tomb offer an interesting case study about Greek, proto-Lucanian, and local pottery styles. These items reflect activities like athletics, warfare, and Dionysian themes, signifying the aristocratic pride and wealth of the tomb's occupant. The vessels showcase red-figure designs, connecting them through a thematic 'red thread.' Despite some damage from ancient pillaging, these grave goods provide a glimpse into the cultural and social context linked to the Italic aristocracy of ancient Peucetia.

Indeed, it is interesting to focus on the images depicted on the only fragmentary red-figure Attic wine cup (usually labelled with the term of kylix) where it is possible to observe both female and male characters interacting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Detail of the decoration of the Attic red-figure kylix, attributed to the Painter of the Naples Hydriskai, 450-425 BCE, from tomb 2/1994, located in site 14 of the archaeological area of Botromagno. Inv. No. 76106, Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation’s Museum, Gravina di Puglia. Image: author’s own elaboration from photos by Nicola Lapacciana, photo courtesy of Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation.

‘Scarlet threads running through the colorful skein of the past’: sashes and fillets

The most obvious detail that we notice is that the female figures on the kylix are shown holding boxes and long textile sashes. To precisely describe the use of these sashes or fillets (a cloth band or sash worn around the head) is a challenge: the images on the cup seem to outline some characters getting ready for an event that is hard to establish precisely. But we know that sashes and fillets are often linked to cultural practices where women with such fillets play a role in the process of honouring human figures. But we also note that this image is unique in the grave itself; the images on the other red-figure vases in tomb 2/1994 - those which were crafted by artisans in Southern Italy - do not show any fillets or sashes. How then is it best to understand this kylix and its images?

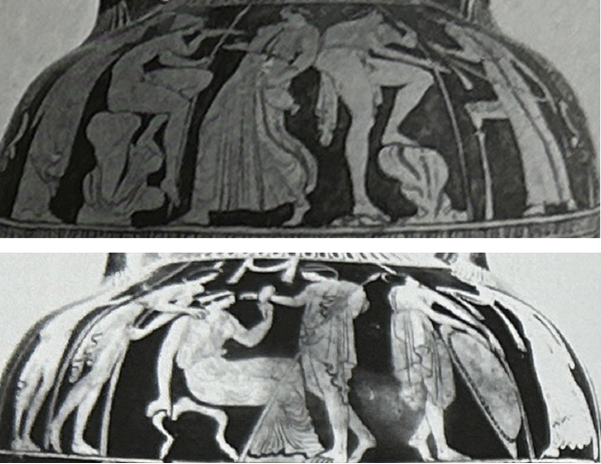

In fact the Attic kylix showing women with sashes might best be interpreted within the wider cultural context rather than in the isolated context of its representation within the tomb. Such images are a common occurrence in other Southern Italian pottery, conveying a wide range of symbolic messages, as is shown by a limited selection of vases produced by the Amykos Painter (c.425-400 BCE), and by artisans who operated shortly before and after him, such as the proto-Lucanian Cyclops Painter (c.425-400 BCE), the Lucanian Palermo Painter (c.410-390 BCE) and the Creusa Painter (c.380-360 BCE) (Figs. 2-5).

Fig. 2. Detail of the decoration of the proto-Lucanian red figure hydria, attributed to the Amykos Painter, c.425-400 BCE, unknown provenance. Inv. No. 91.1.466, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image: (cropped) from museum webpage.

Fig. 3. Detail of the decoration of two proto-Lucanian red figure Panathenaic amphorae, attributed to the Amykos Painter, c.425-400 BCE, from a tomb at Piazza Bovio in Ruvo di Puglia. Inv. No. 88263/4, Museo Nazionale Archeologico di Napoli. Image: author’s own elaboration from Montanaro (2007) figs. 542-543, 619-620).

Fig. 4. Detail of the decoration of a Lucanian red figure bell-krater, attributed to the Creusa Painter, c.380-360 BCE, unknown provenance. Inv. Chr. VIII, Copenhagen National Museum. Image: author’s own elaboration from LCS pl.45.3.

Fig. 5. Detail of the decoration of a Lucanian red figure bell-krater, attributed to the Creusa Painter, c.380-360 BCE, unknown provenance. Inv. No. 29700, War Memorial Museum, Auckland. Image: author’s own elaboration from LCS pl.45.4.

These images show fillets in various scenes with women, warriors, athletes, and gods like Herakles, as well as grave markers. Characters on the vases suggest fillets were used to celebrate, honour, and worship. Female figures holding fillets highlight women's roles as artisans and custodians, tied to celebrating privileged individuals. Male glory is affirmed by these females, reflecting a balance of power and shared cultural concepts like wealth and pride (Figs. 6-7). Such examples reveal a wide cultural understanding and interest in these items in these many contexts.

Fig. 6. Photos of the red-figure proto-Lucanian hydria (left) attributed to the workshop of the Pisticci Painter, end of the fifth century BCE, and the two sides of the red-figure proto-Lucanian lebes (centre and right), attributed to the Cyclops Painter, end of the fifth century BCE, from tomb 2/1994 located in site 14 of the archaeological area of Botromagno. Inv. nos. 76090 and 76093, Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation Museum, Gravina di Puglia. Images: author’s own elaboration from photos by Nicola Lapacciana, photos courtesy of Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation.

Fig. 7. Photos of the red-figure proto-Lucanian hydria (above) and the red-figure proto-Lucanian bell-krater (below), attributed to the Amykos Painter, c.430-410 BCE, from tomb 2/1994, located in site 14 of the archaeological area of Botromagno. Inv. nos. 760840 and 76083, Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation Museum,Gravina di Puglia. Images: author’s own elaboration from Ciancio 1997: 108-109, figures 138-139, and from photos by Nicola Lapacciana, photos courtesy of Ettore Pomarici Santomasi Foundation.

Fillets, images and vases: the many ‘voices’ of a tradition in Peucetia

In summary, the Attic red-figure cup showing women with textile bands can be connected to a wide range of themes shown on vessels crafted in Southern Italy. Hence the decoration of the Attic kylix is harmonically part of a larger symbolic and complex tradition. These depictions also celebrate women as skilled aristocrats crafting luxury fillets for many different events. The grave goods from tomb 2/1994 suggest the Peucetian aristocracy aimed to convey symbolic messages through various vessels. The images on the vessels from Gravina-Botromagno should be viewed as linked to a broader cultural context: the images from a single Peucetian tomb echo some elements of a wider shared cultural background. Despite uncertainties about the reasons behind this choice, comparisons help to better contextualize the images on the vases from tomb 2/1994. The Attic and Italiotes red-figured threads contribute to a shared narrative. They highlight the roles of female figures within the social hierarchy, honouring their skills and societal ties. These artifacts reflect Peucetian aristocrats' pride in their background, culture, wealth, and social status.

Bibliography

LCS= Trendall, A. D. (1967) The red-figured vases of Lucania Campania and Sicily (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Ciancio, A. (1997) Silbíon: una città tra greci e indigeni: la documentazione archeologica dal territorio di Gravina in Puglia dall'ottavo al quinto secolo a. C. (Bari: Levante).

Montanaro, A. C. (2018) 'Death is not for me. Funerary contexts of warrior-chiefs from pre Roman Apulia' in Inszenierung von Identitäten. Unteritalische Vasenmalerei zwischen Griechen und Indigenen, Proceedings of the International Conference (Kolloquium, Berlin, Bodemuseum, 26-28 Oktober 2016), CVA Supplements, 8, eds. U. Kästner and S. Schmidt (München: München: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften): 25-38

Montanaro, A. C. (2007) Ruvo di Puglia e il suo territorio: le necropoli: i corredi funerari tra la documentazione del 19. Secolo e gli scavi moderni (Studia archaelogica 160) (Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider).

Todisco, L. (2012) La ceramica a figure rosse della Magna Grecia e della Sicilia, Vol. I Produzioni, (Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider).

Carlo Lualdi is a classical archaeologist who recently completed his PhD in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His recent studies focus on battle scenes and warfare images from Southern Italy between the end of the fourth and the third century BCE. When he is not analyzing ancient depictions, Carlo enjoys watching fantasy TV series and movies, reading books, comics and manga, walking across the Cotswolds, and taking photos of clouds and sunsets.

Reading and listening at the 'Colossi of Memnon' by Cameron Heagney (April 2024)

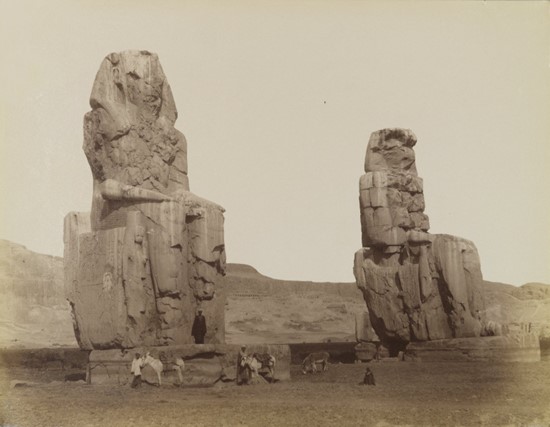

Herodotus was among the first Greek authors to write of the “so many marvellous things” found in Egypt (Herodotus, The Persian Wars 2.35), contributing to a developing interest in Egypt as a region conceived to be full of curious and obscure wonders. But for the growing communities of Greeks and Romans making their journey down the Nile, few spectacles could attract as many visitors as the so-called ‘Colossi of Memnon’. These two enormous sandstone statues depicted Pharaoh Amenhotep III, and were built in the ancient city of Thebes (modern day Luxor) during the fourteenth century B.C. (Fig. 1). Gazing out into the eastern horizon, the two 18-metre statues mark the entrance to the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III and dominated the landscape as the largest monuments in the area. Their magnificent size and antique age were the subject of marvel, but the most wonderous of all of their qualities were the sounds that one of the statues could reportedly produce.

Fig. 1. Photograph of the ‘Colossi of Memnon’ from the 19th century. Brooklyn Museum Accession No. 86.250.23. Image: Photograph by Antonio Beato, Brooklyn Museum.

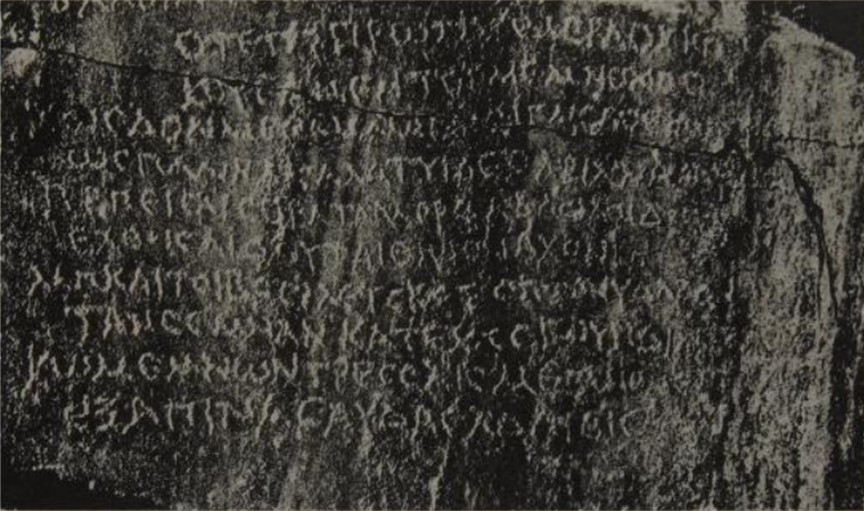

Indeed, as a result of damage and natural erosion, the slight dislocation of the statue’s stones allowed wind and air to pass through the northern Colossus and produce sounds at certain times of day. This curious phenomenon is reported by several Graeco-Roman authors, but it is Strabo who relates that the sound was so lifelike that he was unable to distinguish whether the noise was produced by the statue, or the men stood around its base (Strabo, Geography 17.1.46). Attracting frequent visitors for centuries, the sound of the Colossi of Memnon is referenced to in dozens of graffiti that cover the legs of the statue pair (Fig. 2). These inscriptions attest not only to the fascination with the statues by Graeco-Roman tourists, but also their desire to capture the fleeting moment of marvel in time forever.

Fig. 2. Graffiti covering the right foot of one of the Colossi of Memnon. Image from: Bernand & Bernand (1960) pl. VII).

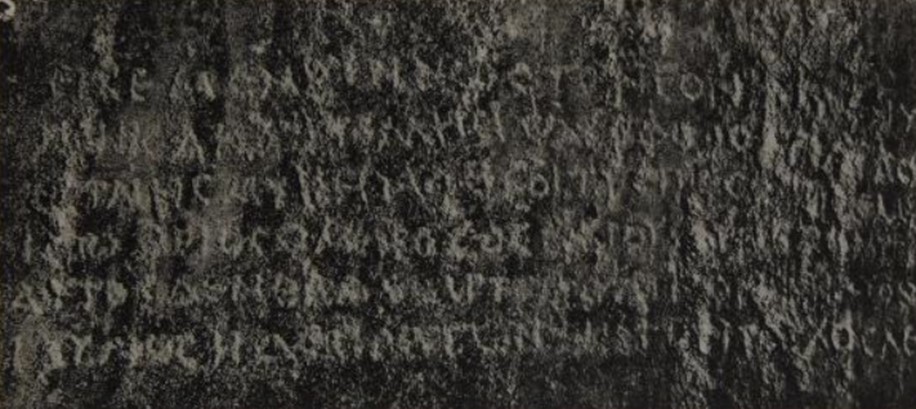

But how could one capture such a moment of wonder with a graffito? For some, a scribble of ‘Agathocles was here’ would do; but in other cases, we can find striking examples of metrical inscriptions that accompany the marvel of the speaking Colossus. One, dated between the first two centuries A.D., is by a certain centurion named Julius, and reads as follows (Fig. 3.):

Fig. 3. Julius' inscription (=Bernand & Bernand 101). Image from: Bernand & Bernand (1960) pl. LVI.

Εἴ γε μὲν οὖν Ἠὼς τὸν ἑὸν [ϕί]λον υἷα δακρύει,

ἠνίκ’ ἂν ἀντέλλῃσι ϕαεσϕόρος ἤμασιν αἴγλην

ἐ[κ] γαίης μύκημα θεοπρεπὲς [ἐκπ]έμπουσα,

ἴστω θεῖος Ὅμηρος, ὃς Ἱλίου ἔ[ννε]πε μῦθον·

αὐτὸς δ’ ἐνθάδ’ ἔων τοῦ Μ[έμ]ν[ον]ος [ἔ]κλυον αὐδῆς.

Ἰούλιος ἦλ[θο]ν ἐγὼν [ἑκα]τόνταρχος λεγεῶνος.

(Appendix 2.101, Rosenmeyer (2018) 238)

If Eos weeps for her own dear son

whenever the bearer of shining light brought radiance to the days,

letting out a roar from the earth worthy of a god,

Know this, divine Homer, he who tells the tale of Troy;

but I myself, standing here, heard the voice of Memnon.

I, Julius, came here, centurion of a legion

It is clear that in attempting to make sense of the Colossi, Julius has chosen – like many others inscribing at the monumental statues – to interpret their marvel with the tools of Homeric storytelling. Indeed, Homer is mentioned by name to “know” the statue pair as Memnon, and the vocabulary used in the first two lines are recognisable from the mention of Eos’ mourning of Memnon in the Odyssey (Odyssey 4.188). But this inscription, composed in dactylic hexameter, is consciously Homeric in its choice of language: Eos is ϕαεσϕόρος, the ‘bearer of shining light’, ringing of Homeric divine epithet; by the same measure αἴγλη (‘radiance’) is found repeatedly in Homeric poetry (Iliad 2.458; Odyssey 4.45, 6.45, 7.84), formulated in dazzling and specifically visual terms. Moreover, Julius makes use of the Homeric Ionic dialect of Greek, electing to use lengthened and epic forms of verbs throughout.

The inscriber clearly identifies the statue with the Memnon of Homeric poetry, and this interpretation is enacted in the vocalisation of this graffito. But Julius’ inscription, capturing the moment of spectacle as if the statue produces a heroic roar, can conversely be read to provide a commentary on Homeric storytelling. Indeed, it is in the Odyssey that Eos weeps for her fallen son Memnon, but Julius recognises in the monumental statue of Amenhotep III that the heroic Memnon is alive and passionately vocal. In doing so, the heroic ‘roar’ of the Colossus is turned into a moment of reflection upon the veracity of Homeric storytelling. Julius, a Roman centurion presumably garrisoning Upper Egypt, chooses to interpret Egyptian antiquity through expression of Greek cultural heritage; as an occupying force, his appropriation of the monument may speak to Roman cultural tastes and value judgements of ‘Greek’ arts over ‘Egyptian’ ones.

Another inscriber identified on the Colossi of Memnon is Julia Balbilla, a learned poet who travelled in Hadrian’s imperial retinue across the Roman Empire. In one of her poems (Fig. 4.), dated to 130 A.D., Balbilla’s encounter with the empress Sabina is memorialised in the shadows of the miraculous statues:

Ὅτε τῇ πρώτῃ ἡμέρᾳ οὐκ ἀ-

κούσαμεν τοῦ Μέμνονος.

Χθίσδον μὲν Μέμνων σίγαις ἀπε[δέξατ’ ἀκ]οίτα[ν],

ὠς πάλιν ἀ κάλα τυῖδε Σάβιννα μό[λοι.]

Τέρπει γάρ σ’ ἐράτα μόρϕα βασιλήϊδος ἄμμας·

ἐλθοίσαι δ’ [α]ὔται θήϊον ἄχον ἴη

μὴ καί τοι βασίλευς κοτέσῃ· τό νυ δᾶρον ἀτά[ρβης]

τὰν σέμναν κατέχες κουριδίαν ἄλοχον.

Κὠ Μέμνων τρέσσαις μεγάλω μένος Ἀδρι[άνοιο]

ἐξαπίνας αὔδασ’, ἀδ’ ὀΐοισ’ ἐχάρη.

(Appendix 2.30, Rosemeyer (2018) 147-148)

When on the first day

we did not hear Memnon.

Yesterday Memnon received Hadrian’s wife in silence,

so that beautiful Sabina might come here again.

For the lovely form of our royal mother pleases you;

when she arrives, let a divine shout come for her;

lest the king grows angry with you. And now fearlessly

you have captivated his noble wedded wife for too long.

Memnon who trembled at the power of great Hadrian

suddenly spoke, and she rejoiced in hearing it.

(Author's own translation).

Fig. 4. Balbilla's inscription (=Bernand & Bernand 30). Image from: Bernand & Bernand (1960) pl. XLIX.

Balbilla’s poetry on the Colossi has been described as having a ‘Sapphic voice’ for two reasons. First, her choice to write in the distinctive Aeolic dialect (the same dialect of Ancient Greek as the lyric poet Sappho), setting her graffiti apart from the Homeric-Ionic dialect of other metrical inscriptions. Second is her framing of erotic encounters in such fluid temporalities. Balbilla trains her lyric-poetic voice on the fleeting moments of the past, present, and imminent future, and seems less interested in the monumental ‘Homeric’ Memnon as she is in the empress’ presence at the epic encounter (cf. Sappho fr. 16). Sabina, the wife of Hadrian, is the real object of marvel for Balbilla; her eroticised descriptions of the empress have been read as pastiches of Sappho’s own description of feminine beauty (Sappho fr. 16.17-18, 17.2), and Balbilla’s poetic gaze seems fixed upon Sabina despite the epic miracles at present.

What does it mean for Balbilla’s poetry to be inscribed very publicly upon the Colossus? Her verses celebrated the imperial visit to Upper Egypt, and are testament to her learned poetic skill, but they frame a very different encounter to the other inscriptions at the Colossi. Where the hexametrical inscriptions in epic dialect and Homeric language ask their listeners to interpret the space in the world of early Greek epic, Balbilla’s Aeolisms and Sapphic voice mark the Colossi as a place of erotic, lyric encounters. As we have seen, both types of inscriptions are intentionally archaising, making use of older vocabulary and dialects to associate themselves with the rich Greek literary tradition. But Balbilla’s inscribed poetry is unique even in this sense; her choice to imitate Sapphic lyric invites an alternate, reinterpretative reading – perhaps listening – of the space as the site of a fleeting erotic encounter.

In our interpretation of these metrical inscriptions, we can hear a polyphony of voices, genres, and gendered encounters recorded by previous visitors. This aspect, of reading and listening had great sway over how the Colossi were remembered by Graeco-Roman tourists. But how can we incorporate the miraculous ‘voice’ of the statue into our understanding of the ‘soundscapes’ of these material and epigraphical encounters?

Some authors report a deep, vocal sound emerging from the northern Colossus: for Pliny, it was a creaking rattle at dawn (Pliny, Natural History 36.11), and Lucian reports “a roar” heard from the statue (Lucian, Toxaris or Friendship 27). Julius’ inscription, consciously reflecting upon Homeric storytelling, dictates a heroic ‘listening’ of these sounds. We are asked to hear a heroic roar in the Colossus’ μύκημα (‘roar’), and interpret the statue with reference to the Homeric world of epic. In this way, the reader (or rather, the listener) and the inscriber collaborate to affirm the appropriation of the Egyptian monument. Should one consent to the interpretation of the statue’s roars as the roars of the Homeric Memnon, as Julius and many others have, the statues of Amenhotep III are rendered objects of Greek cultural reflection and discourse.

Other authors, however, reported that the statue’s voice was far more musical in quality. Pausanias likened the Colossus’ ‘voice’ to “a kithara when a string has been broken” (Pausanias, Periegesis 1.42.3); Philostratus’ artistic description recorded that the sound was like a plectrum striking a lyre (Philostratus, Imagines 1.7.20-25). Should this have been the case, Balbilla’s markedly Aeolic lyric poetry, when read aloud, may have been accompanied by the musical song of the monument’s ‘voice’. Her poetry sought to capture a fleeting and deeply personal moment in time, less interested in the Colossus and more in her time with the empress; yet, in this ‘listening’, the Colossus’ musical voice may have had the potential to compliment the poem’s registration of the monument as the site of erotic encounter and personal storytelling.

By the third century A.D., it is thought that the northern statue was repaired (perhaps during Septimius Severus’ visit, cf. Historia Augusta Septimius Severus 17.4) and, as a result, had stopped producing the miraculous noise. For this reason, we may never be able to know if the Colossus’ ‘voice’ accompanied an epic or lyric ‘listening’ of the inscribed poetry. There is potential, however, that visitors encountered both; Callistratus’ account of the statue’s voice reports both “joy and delight” at dawn as well as “piteous and mournful groans in grief” at dusk (Callistratus, Descriptions 9.1). In whatever manner we choose to understand the ‘soundscapes’ of the Colossi of Memnon, the metrical inscriptions on the statues nonetheless had the capacity to determine a visitor’s experience and interpretation of the space. They triangulated meaning around highly allusive poetry, the audible ‘voice’ of the Colossus, and the listener’s experience of the site. Perhaps it is a greater marvel that such short, rhythmic verses could determine concepts as large as time, myth, and memory for Greek and Roman visitors!

Bibliography

Primary sources:

Herodotus, The Persian Wars, books 1-2, trans. A. D. Godley, Loeb Classical Library 117 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920).

Strabo, Geography, book 17, trans. H. L. Jones, Loeb Classical Library 267 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932).

Homer, Iliad, books 1-12, trans. A. T. Murray, Loeb Classical Library 170 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924).

Homer, Odyssey, books 1-12, trans. A. T. Murray, Loeb Classical Library 104 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1919).

Sappho, Lyric fragments, trans. D. A. Campbell, Loeb Classical Library 142 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

Pliny, Natural History, books 36-37, trans. D. E. Eichholz, Loeb Classical Library 419 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

Lucian, Toxaris, or Friendship, trans. A. M. Harmon, Loeb Classical Library 302 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1936).

Callistratus, Descriptions, trans. A. Fairbanks, Loeb Classical Library 256 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

Pausanias, Description of Greece, books 1-2, trans. W. H. S. Jones, Loeb Classical Library 93 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1918).

Philostratus the Elder, Imagines, trans. A. Fairbanks, Loeb Classical Library 256 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

Historia Augusta, Septimius Severus, trans. D. Magie, Loeb Classical Library 139 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022).

Secondary sources:

Baumbach, M. (2017) ‘Poets and Poetry’ in The Oxford Handbook to the Second Sophistic, eds. D. S. Richter & W. A. Johnson (New York: Oxford University Press) 493-508.

Bernand, A. and Bernand, E. (1960) Les Inscriptions Grecques et Latines du Colosse de Memnon (Paris: Institut Francais d'Archéologie Orientale du Caire).

Bowersock, G. W. (1984) ‘The Miracle of Memnon’, The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 21 (1): 21-32.

Moyer, I. (2011) Egypt and the Limits of Hellenism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Rosenmeyer, P. A. (2008) ‘Greek Verse Inscriptions in Roman Egypt: Julia Balbilla’s Sapphic Voice’, Classical Antiquity 27 (2): 334-358.

Rosenmeyer, P. A. (2018) The Language of Ruins: Greek and Latin Inscriptions on the Memnon Colossus (New York: Oxford University Press).

This post was written by Cameron Heagney, a postgraduate student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick working towards a taught MA in Visual and Material Culture of the Ancient World. Cameron’s interests lie in expressions of identity, ethnicity, and community in the Mediterranean world. He has most recently been working on textiles, religion and personhood in Late Antiquity.

A Macedonian Grey Ware Mug from Thessaloniki: 'terra sigillata' or not? by Vaggelis Papaioannou (February 2024)

´Terra sigillata´ is a term which refers to the pottery produced, distributed and used throughout the Roman Empire. Pots which belong to that very broad category were produced in every corner of the Mediterranean and European world, from Spain, France and Germany to Tunisia, Greece, Turkey and Lebanon, over 9 centuries (from the 2nd century BC to the 7th century AD). The term generally denotes vessels used on tables, such as plates and cups, that bear a glossy red slip with various kinds of decoration, while the manufacturers very often leave their mark with a stamp.

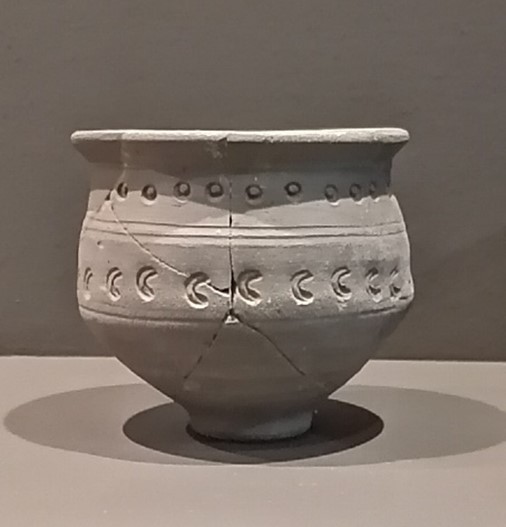

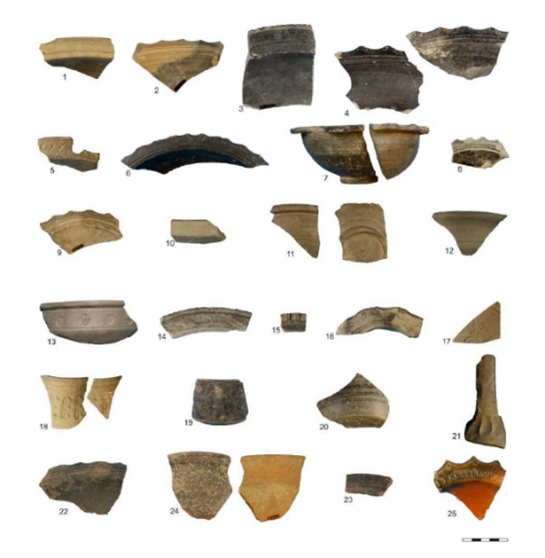

On looking at ´terra sigillata´ objects exhibited in museums all around Europe the lack of uniformity is obvious. All the above-mentioned production centres made different kinds of ´terra sigillata´, distinguished by the color of the clay and the slip, and the repertory of shapes, or the decoration. A visit to the Roman Agora Museum in Thessaloniki offers a glimpse of different classes of red-slipped productions from the Mediterranean, for instance the African and Phocean Red Slip Ware. Eventually, the visitor will come across a series of table vessels with a glossy slip, which in many ways is unlike all the other ´terra sigillata´- red slipped products (Fig.1). Its name is Macedonian Grey Ware (MGW hereafter).

Fig. 1. Macedonian Grey Ware mug in the Roman Agora Museum, Thessaloniki, (author's own photo).

Our object (Fig.1) is exhibited in the Ancient Agora Museum of Thessaloniki (inv.no. ΡΑ1728) and was found inside a late Roman shop, at the south wing of the ancient (Roman) agora. We are looking at a mug, a vessel for drinking. It has an outcurved rim, conical lower body with a flat ring base and has no handles. On the exterior surface it bears stamped decoration, which is divided into two zones. The upper zone consists of circle stamps, while the lower has semi-crescent motifs. The two zones are divided by two shallow grooves and a third one separates the lower zone from the rest of the body. Its distinctive features are the glossy grey slip and the sparkly micaceous grey fabric, that differentiate it from the rest of the ´terra sigillata´ family and result from a burnishing procedure and a lack of oxygen during its firing in the kiln (Fig.2). All the examples of the MGW are made of grey clay and bear grey slip, apart from only very few examples fired in brownish clay and coated with a red slip.

Fig. 2. Stereoscopic shot of an MGW sherd section from Phillippi. Image: Zachariadis (2018) Fig. 4a.

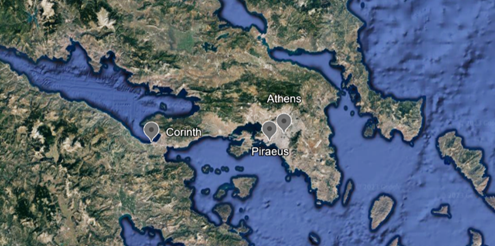

MGW is known by many other terms, some more helpful than others, such as ´Macedonian terra sigillata grise´ or ´terra nigra´, and is a category of tableware that covers the chronological span of the late Roman era, especially the spectrum from the second half of the 4th century until the middle of the 6th century AD. Unlike the more widely distributed ´terra sigillata´, it was circulated mostly around Macedonia and the southern Balkans. The majority of the published material comes from Stobi (North Macedonia), sites of Northern Greece (e.g. Philippi, Thessaloniki, Thassos), as well as sites in Bulgaria and Romania, while few examples managed to reach southern Greece, e.g. Athens and Corinth (Fig.3). The high frequency of the ware in the northern area has always been among scholars an adequate reason to attribute the production of MGW to Macedonia, with Stobi (Axios Valley), Upper Strymon Valley and Thessaloniki having been proposed as possible production centres. More intensive petrographic examinations of finds from Northern Greece and Southern Balkans will hopefully give an answer to the question of provenance.

Fig. 3. Maps depicting sites where MGW has been found. (Images: ©

Google Earth, Vaggelis Papaioannou).

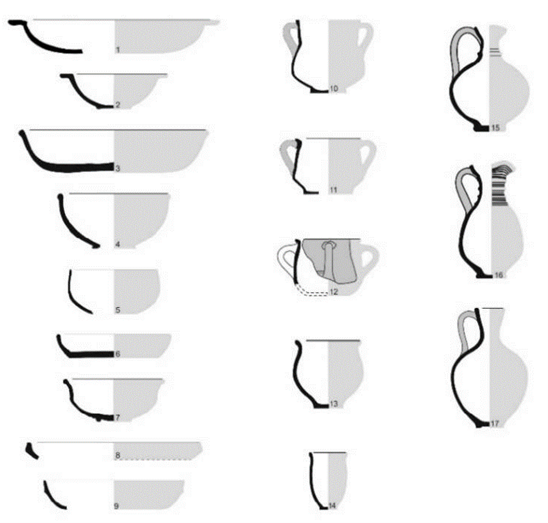

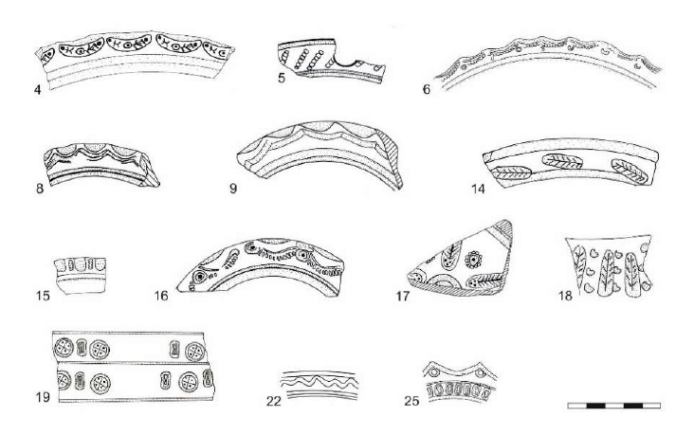

The repertoire of MGW vessel shapes consists of open and closed forms alike, while bowls and dishes predominate over mugs and jugs. The first typology, after only a brief presentation of the ware in Late Roman Pottery (1972) and A Supplement to Late Roman Pottery (1980) by John Hayes, was established by Anderson-Stojanovic (1992) based on the material from Stobi, North Macedonia and contained 11 shapes, of which 7 are bowls and dishes. The remaining four are mugs and jugs. Recent excavations and studies of pottery material from Thessaloniki and Philippi (in Zachariadis 2018) have considerably expanded Stojanovic´s typology and led to a list of 17 types and still counting (Fig.4). Our mug belongs to the type drawn under number 13. It is often hard to distinguish between those main types and their many alternatives, given also the fragmentary state of the majority of those, so the actual repertory has to be even greater (Fig.5). Pots and lids produced with the same fabric are also reported, along with shapes associated with special functions, like bowls with plastic (made with a mould) handles. Currently, my collaboration with the French School at Athens and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Serres in an excavation of another Roman and Early Byzantine city in Northern Greece, Terpni, and its pottery study has yielded valuable information regarding the ware´s vessel variety and distribution.

Fig. 4. The typological spectrum of MGW, based on finds from various sites in Northern Greece.

Image: Zachariadis (2018) Fig. 1.

Fig. 5. MGW sherds from Philippi.

Image: Zachariadis (2018) Fig. 5.

The decoration of these vessels varies quite a bit, although, apart from the metallic grey slip that gives significant aesthetic value to the ware, is common feature of MGW (Fig.6). Impressed and stamped floral and geometric patterns, incised ridges, are often combined as in the mug from Thessaloniki and are found on the rims, on the interior bottom and sometimes on the external surface of the vases. One of the most distinctive types of decoration of the MGW, hardly attested in other tableware shapes, is the presence of scallop shaped rims. These are usually combined with the other decoration options. All in all, taking into consideration the grey metallic slip and the decoration as described above, it is not unreasonable to suggest that the ware likely initially imitated metallic prototypes.

Fig. 6. Decorative motifs on finds from Philippi.

Image: Zachariadis (2018) Fig. 2.

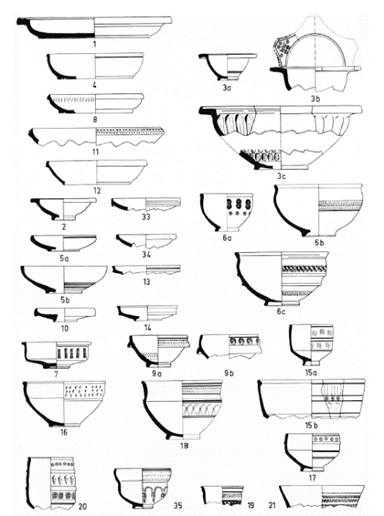

Fig. 7. Repertory of shapes and decoration of Gaulish Grey Ware.

Image: Rigoir (1968) Fig. 14.

Speaking of imitations, despite the fact that MGW stands alone compared to the other slipped tablewares, it has some features that are very reminiscent of other wares and indicate stylistic influences. For example, the stamped motives on MGW are identical to those attested in other late Roman fine wares, as well as in terms of shape. Many scholars have highlighted the resemblance of some of the shapes with African forms, while in Philippi we have evidence that an African Red Slip form (Type 61 of the Hayes typology for the Tunisian products) was directly copied (Fig.4.8). So far, my recording of the material from Terpni has enabled me to add two more forms directly copied in MGW -simultaneously expanding the typology even further-, the form 67 and form 1 of Hayes typology for African and Phocean red slipped vessels respectively.

The Western equivalent of MGW is the Gaulish Grey Ware. The resemblance between the two wares is striking, in terms of fabric and decoration, but also of shapes, even though the latter does not appear to produce jugs (Fig.7). For instance, our mug from Thessaloniki is quite similar to the mug under number 17. But how can that uncanny resemblance be convincingly explained, given the restricted number of Gaulish imports in Northern Greece, the regional character of the MGW distribution and the dependance of the Gaulish shapes on those of the earlier Samian production? That question, in my view, could be answered only in light of new finds from the area of Northern Greece.

One might argue that Macedonian Grey Ware is treated, bibliographically speaking, as the ´´black sheep´´ (or should we say … grey?) of the ´terra sigillata´ family, since very little attention has been given to it and given the features that separate it from the other slipped tablewares of the time, such as the slip color or the restricted distribution patterns. MGW does not fall short in terms of quality or significance of the information it is capable of giving, especiallyin relation to the late Roman pottery production and distribution patterns of Macedonia. All these assets and the veil of mystery still covering matters of typology, chronology and production create the imperative need for approaching these research desiderata, so that this grey ware can finally exit the … grey zone!

Bibliography

Abadie-Reynal, C. andSodini, J-P. (1992) La Ceramique Paleochretienne de Thasos (Aliki, Delkos, Fouilles Anciennes) (Athens, French School at Athens)

Anderson-Stojanovic, V.R. (1992) Stobi. The Hellenistic and Roman pottery (New Jersey, Princeton University Press).

Chrysostomou, A. (2010)´´ Late Antique pottery from Edessa and Almopia in the prefecture of Pella´´[in Greek],in Late antique pottery from Greece. Proceedings of Scientific Meeting. Thessaloniki, 12-16 October 2006, eds. D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi and D.Kousoulakou (Thessaloniki, Aristostle University), pp 505-519.

Graekos, I. (2010) ´´Closed pottery assemblages from cemeteries dating from Late Antiquity at Nea Kallikrateia, Chalkidiki´´ [in Greek],inLate antique pottery from Greece. Proceedings of Scientific Meeting. Thessaloniki, 12-16 October 2006, eds. D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi and D.Kousoulakou (Thessaloniki, Aristostle University),pp 429-443.

Grigoropoulos, D. (2010)´´ Tablewares and amphorae in Late Roman Piraeus: General trends in ceramic supply between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD´´ [in Greek], in Late antique pottery from Greece. Proceedings of Scientific Meeting. Thessaloniki, 12-16 October 2006, eds. D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi and D.Kousoulakou (Thessaloniki, Aristostle University),pp 671-688.

Hayes, J. (1972) Late Roman Pottery (London, The British School at Rome).

Hayes, J. (1980) A Supplement to Late Roman Pottery (London, The British School at Rome).

Hayes, J. (1997) Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery (London, British Museum).

Karivieri, A., Forsell, R., andTulkki, C. (2010) ´´Late Roman and Early Byzantine pottery from Arethousa´´[in Greek], in Late antique pottery from Greece. Proceedings of Scientific Meeting. Thessaloniki, 12-16 October 2006, eds. D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi and D.Kousoulakou (Thessaloniki, Aristostle University), pp 421-428.

Mpoli, K. and Skiadaresis G. (2001) ´´The stratigraphy from the southern wing´´ [in Greek], in Ancient Agora of Thessaloniki. Proceedings of the two-day conference for the works of the years 1989-1999, ed. P. Adam-Veleni (Thessaloniki, University Studio Press), pp 87-104.

Panti, A. (2010) ´´Late antique pottery from the eastern cemetery of Thessaloniki´´ [in Greek],in Late antique pottery from Greece. Proceedings of Scientific Meeting. Thessaloniki, 12-16 October 2006, eds. D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi and D.Kousoulakou (Thessaloniki, Aristostle University), pp 466-485.

Rigoir, J. (1968) ´´Les sigillées paléochrétiennes grises et oranges´´, Gallia, Vol.26, No 1, pp 177-244.

Tsoneva, A. (2016) ´´Towards the typology of Macedonian Gray Ware: unpublished vessels from the territory of Parthicopolis, Bulgaria´´, Studia Academica Šumenensia, Vol 3, PhD Suppl., pp 42-55.

Zachariadis, S. (2018) ´´Regarding the gray ware from Philippi´´ [in Greek], in LEPETYMNOS. Studies in Archaeology and Art in memory of Georgios Gounaris. Late Roman, Byzantine, Postbyzantine period, eds. Ath. Semoglou, I.P.Arvanitidou, Em.G. Gounari (Thessaloniki, Vizantinos Domos), pp 499-520.

This post was written by Vaggelis Papaioannou, MA by Research student in the Department of Classics and Ancient History, at the University Warwick. Vaggelis has worked on archaeological sites and material around Greece, includingThassos, Epidauros and Kos and his research interests include Roman and Late Roman/Early Byzantine pottery of the Eastern Mediterranean and lychnology, with special emphasis on matters of production, regionality and distribution of Roman pots. He is currently studying pottery assemblages from Rafina in Attica and from Terpni in Northern Greece.

Once a musician, always a musician by Francesca Modini (January 2024)

Probably in the last quarter of the third century CE, a Roman citizen with Greek origins named Marcus Sempronius Nicocrates was laid to rest in a fairly elaborate marble sarcophagus, whose lid is now in the Townley ‘Bronzes and Sculptures’ Collection at the British Museum (Figs. 1 and 2). The lid was found on the Via Flaminia in Rome at the end of the seventeenth century; it features two scenes flanking an inscription, in addition to what must have been the portrait of Nicocrates, on the right side. If we look at the two reliefs, we get the sense that Nicocrates must have been some sort of artist and performer: the two female figures in the scene are obviously Muses, the Muse on the right is leaning on what looks like a lyre, whereas a scroll and a scroll box can be found in the panel on the left. The male figures on the lid are reading or declaiming to the Muses in front of them; even more clearly, actor masks decorate both scenes.

Fig. 1. Nicocrates' sarcophagus. Recto. Townley - 'Bronzes & Sculptures, British Museum No. 1805,0703.152. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Fig. 2. Engraving of the same sarcophagus, from the Townley Archive, TY 12/4, fo. 94. Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Yet it is only when reading the inscription flanked by the reliefs (IGUR 1326 = GVI 1049) that we find out precisely what kind of performer Nicocrates was:

Μ(άρκος) ∙ Σεμπρώνιος Νεικοκράτης

ἤμην ποτὲ μουσικὸς ἀνήρ,

ποιητὴς καὶ κιθαριστής ∙

μάλιστα δὲ καὶ συνοδείτης ∙

πολλὰ βυθοῖσι ∙ καμών ∙ (5)

ὁδηπορίες δ’ ἀτονήσας ∙

ἔνπορος εὐμόρϕων γενόμην,

ϕίλοι, μετέπειτα ∙ γυναικῶν ∙

πνεῦμα λαβὼν δάνος οὐρανόθεν

τελέσας χρόνον αὖτ’ ἀπέδωκα, (10)

καὶ μετὰ τὸν θάνατον ❦

Μοῦσαί μου τὸ σῶμα κρατοῦσιν.

M. Sempronius Nicocrates

I was once a musician,

a poet and a kithara-player,

and above all the member of a synod of artists.

After labouring much at sea (5)

exhausted from the journey

I then became, friends, a merchant

of beautiful women.

I received my breath on loan from the sky

and come to the end of my time, I returned it. (10)

Even after death,

the Muses are in charge of my body.

(Author’s own translation)

As the deceased himself explains, he was ‘once a musician, a poet’ and played the kithara, a concert lyre with a wooden soundbox bigger than common bowl lyres, and therefore able to produce a more powerful sound (Figs. 3 and 4; West (1992)). At first, Nicocrates pursued a professional career through his association with a synod of artists, which may have performed at numerous festivals and contests throughout the Empire, and it is as a musician that Nicocrates is recorded in repertoires of ancient performers (Stephanēs (1998) no. 1781; Fauconnier (2023) no. 207; connectedcontests.org). Since this activity forced him to go on exhausting musical tours, however, at last Nicocrates decided for a career change: he gave up performing and – in his own words – reinvented himself as a ‘merchant of beautiful women’. Much as in our own time, in antiquity, performative arts were clearly not the most profitable of activities; on the contrary, besides being legal and largely morally accepted, human trafficking, slavery and prostitution were always in high demand.

Fig. 3. . Cyzicus, 460–400 BC, elektron stater with kithara. Berlin MK AM 18203046. Image: © ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Fig. 4. Seated woman playing the kithara (possibly in the process of tuning the instrument), with a younger female behind her chair. Wall painting from Room H of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, ca. 50–40 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, MET 03.14.5. Image: public domain.

Despite the detailed and strikingly honest account of his professional woes and choices, however, Nicocrates’ personal narrative has only been partially unpacked. In one of the earliest modern analyses, Henri-Iréné Marrou (1938) listed the sarcophagus as an example of ‘intellectual scenes on Roman funerary monuments’, only mentioning Nicocrates’ career change as sign of his ‘lively and picaresque life’ (1938). Similar treatments are found in studies such as Wegner’s (1966) repertoire of Muses on sarcophagi, or Webster’s (1995) collection of monuments featuring dramatic elements, where the focus is on iconographical features and their significance. Even when closer attention has been paid to the shift between Nicocrates’ former artistic life and his later activity as a procurer of women, the inscription has not always been taken seriously. According to Susan Walker (1990), for example, ‘the text is self-mocking in tone’ and ‘was evidently composed to amuse the passer-by’.

Yet, while we cannot exclude the presence of an ironic undertone in the epitaph, the way Nicocrates decided to portray his life after his death must also have been a very serious affair for him (cf. Ewald 1999). Indeed, no matter how we read the mention of his career change and the reasons behind it, the once-musician still chose to be remembered as a poet and kithara-player, an idea that culminates in the closing image of the Muses ‘in charge’ of his body, in turn mimicked by the word order of l. 12 (Μοῦσαί and κρατοῦσιν ‘surround’ τὸ σῶμα; and the verb κρατοῦσιν may also be read a clever allusion to Νεικο-κράτης). This element creates a striking symbiotic relationship between the inscribed text and the sarcophagus lid and its iconography: it is precisely the Muses carved on the lid who are now in power of Nicocrates’ human remains. In a sense, the motif of female beauty mobilised by Nicocrates’ second career is thus recalled and sublimated through his intimate relationship with the Muses. At the same time, the Muses’ control, both textual and iconographical, over Nicocrates after death serves to remind the passer-by that, no matter what Nicocrates ended up doing professionally, his identity as ‘man of the Muses’ (μουσικὸς ἀνήρ, l. 2) continued to be self-defining for him, and will now be what he is forever remembered for.

As if to confirm this, Nicocrates’ artistic self-presentation is further enhanced by the epic character of his personal narrative. The description of his tiring tours as a professional musician (‘after labouring much at sea | exhausted from the journey’, πολλὰ βυθοῖσι ∙ καμών ∙ | ὁδηπορίες δ’ ἀτονήσας, ll. 4–5) is a deliberate echo of the voyage undertaken by Odysseus, who ‘suffered many woes in his heart at sea’ (πολλὰ δ᾿ ὅ γ᾿ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν, Homer Odyssey 1.4). As was fitting for such an impersonation, this epic portrait is delivered in dactylic metres, a metrical form, that is, related to the dactylic hexameter of the Homeric tradition (West 1982).

Overall, Nicocrates’ sarcophagus reveals the role – so far mostly neglected – that music played in the culture and self-presentation of Roman Greeks down to Late Antiquity. For imperial era musicians, it was clearly a source of pride, and a mark of identity, to be recognised as such – even when one stopped being a professional performer like Nicocrates. And while Nicocrates left his musical profession, dozens of imperial inscriptions point to kithara-players and other musicians who, despite hardships and uncertain profits, continued touring imperial cities with success, receiving crowns, citizenships and similar honours.

Bibliography

Ewald, B.C. (1999) Der Philosoph als Leitbild: Ikonographische Untersuchungen an römischen Sarkophagreliefs (Mainz, Verlag Philipp von Zabern) pp. 111–13, 117, 122, 124–5, 216 no. 17.

Fauconnier, B. (2023). Athletes and Artists in the Roman Empire: The History and Organisation of the Ecumenical Synods (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Hemingway, C. (2002) ‘The kithara in ancient Greece’, metmuseum.org.

Marrou, H. (1938) MOYCIKOC ANHP: Etude sur les scènes de la vie intellectuelle figurant sur les monuments funéraires romains (Grenoble, Didier et Richard) pp. 94–5 no. 93, pp. 194, 209–13, 230, 246–7.

Stephanēs, I.E. (1988) Διονυσιακοί τεχνίται. Συμβολές στην προσωπογραϕία του θεάτρου και της μουσικής των αρχαίων Ελλήνων (Hērakleio, Panepistēmiakes Ekdoseis Krētēs).

Walker, S. (1985) Memorials to the Roman Dead (London, British Museum Publications) p. 60 no. 48.

Walker, S. (1990) Catalogue of Roman Sarcophagi in the British Museum, CSIR Great Britain, vol. 2.2 (London, British Museum Publications) p. 28 no. 25.

Webster, T.B.L. (1995) Monuments Illustrating New Comedy, 3rd ed. revised and enlarged by J. R. Green & A. Seeberg (London, Institute of Classical Studies) p. 502 no. 6RS.24.

Wegner, M. (1966) Die Musensarkophage (Berlin, Verlag Gebr. Mann) p. 25 no. 45.

West, M.L. (1982) Greek Metre (Oxford, Oxford University Press) p. 176.

West, M.L. (1992) Ancient Greek Music (Oxford, Oxford University Press) p. 50.

Online Resources:

British Museum sarcophagus: britishmuseum.org

Database on post-classical agonistic networks, including musicians: connectedcontests.org

Dr Francesca Modini is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Warwick. Her current research explores the role of poetry and music in the self-definition of individuals as well as social and ethnic groups living under Rome. She has published on the post-classical reception of archaic song culture (her latest article can be found here). Her book, forthcoming for Cambridge University Press, is the first study of the persistence and significance of ancient lyric poetry in imperial Greek culture.