2025

Points in Time: The Long Shadow of the Montecitorio Obelisk, by Chris Parr

Fig. 1: The obelisk in the market square in Ripon (photo by author).

The 71-foot-tall obelisk now standing proudly in the Piazza di Montecitorio in the centre of Rome is far more ancient than its counterpart in Ripon. The Montecitorio obelisk (Fig. 2) was commissioned as one half of a pair of obelisks by Psamtik II of Egypt the third king of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, who ruled from 595 to 589 BC. The obelisk was cut from the living rock as a single shaft of rose granite in the quarries near Aswan during his short reign. Psamtik II then had this obelisk and its twin counterpart transported down the River Nile to Heliopolis, now part of the modern city of Cairo. There, the obelisks were set up at the sanctuary to the sun god Ra, alongside many other pairs similar pairs of obelisks already dedicated by Psamtik II’s predecessors.

Fig. 2: The Montecitorio obelisk in the Piazza di Montecitorio, Rome (photo by author).

The relationship between obelisks and the sun was emphasised by an obelisk's shape, which imitated a sunbeam, and how its polished granite surface reflected sunlight to demonstrate the power of the sun. The hieroglyphic inscription on the obelisk validated Psamtik II’s role as the ruler of a united Egypt and chosen son of Ra, whilst a depiction of a sphinx on the pyramidion (tip of the obelisk, often covered in precious metal) was the traditional symbol of the king’s ability to defend Egypt. Even though we might think of Psamtik II’s early sixth-century BC obelisks as exceptionally ancient in their own right, the Egyptians considered obelisks to be an archaic monumental form by the Late Period (c. 664 – 332 BC). The first obelisks are thought to have been produced nearly 2000 years earlier during the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2575-2465 BC). Psamtik II’s obelisks were an appeal to the ancient traditions and godlike kings of Egypt’s remote history, signalling an attempt to return to the ‘glory days’ of Egypt’s past. These obelisks were the physical representation of a political and religious statement from Psamtik II that he was the divinely appointed king of a newly united Egypt, a statement that may have resonated with the man responsible for the next phase of the obelisk’s life.

Fig. 3: The Flaminio obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo, Rome (photo by author).

It was Augustus who had this obelisk and the Flaminio obelisk [Figure 3] brought from Heliopolis to Rome in 10 BC. This was no routine transport operation: special ships had to be constructed to bring the obelisks down the Nile from Heliopolis to Alexandria, across the Mediterranean, and then up the Tiber to Rome. These ships essentially had three parts: one ship at the front where a mast and oarsmen could propel the vessel, and two ships behind that could carry the obelisk suspended on planks between them (Fig. 4). Pliny the Elder commented that these ships attracted a lot of attention, and that one was even set up on display in a permanent dock at Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) to celebrate the feat (Pliny, NH 36.70).

Fig. 4: A sketched reconstruction of the Roman double ship that would have brought obelisks to Rome (Wirsching (2000) fig. 7).

In Rome, 1323 miles away (as the crow flies) from Heliopolis, the obelisk was erected on the Campus Martius in 10 or 9 BC and became the gnomon (central dial) of a meridian complex known as the Horologium Augusti, designed by the mathematician Facundus Novius. The complex featured a single bronze guideline (the meridian line) with 360 crosslines marking the degrees of the solar year, grouped into 12 sections to represent the months of the year. The guideline charted the length of the shadow cast by the obelisk at midday throughout the year, with the idea that an observer could note the position of the shadow cast by the obelisk’s tip on the meridian line at noon on a certain date, then return on the same date a year after and the shadow should be at the same spot. Unfortunately, due to the fact that the solar year is 365-and-one-quarter days long, the astute observer would have noticed that the shadow is ever so slightly off the mark from year to year – instead, had the observer (hopefully with a very good memory) returned every four years to find the shadow cast in exactly the same spot as it was 4 years previously, thanks to the addition of a leap day in Augustus’ new calendar.

Despite all this attention to detail, Pliny (NH 36.73) observed in the 70’s AD that the readings had been inaccurate for about thirty years, probably due to the settling of the obelisk into the soil of Rome’s Campus Martius. Accordingly, the meridian line was reset shortly afterwards, probably after the fire of AD 80 when the ground level was raised by over a metre. The meridian was such a distinctive feature of the Campus Martius (later known as the Montecitorio obelisk) that it was depicted on the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius (Fig. 5), erected to commemorate the emperor after his death in AD 161, as a representation of the area in which it was located.

Fig. 5: One of the faces of the base of the column of Antoninus Pius, now held in the Vatican Museums, Vatican City, Arch Vat XVIII.27.22 (Vogel (1973) ill. 3). A semi-nude male figure (left), a personification of the Campus Martius, holds the Montecitorio Obelisk in his left hand.

This meridian function kept the original Egyptian association of the obelisk with the sun, which Augustus also emphasised in the new inscription he added to the obelisk’s base, describing it as a soli donum (gift to the sun – CIL 6.701 and 6.702 (Fig. 6). The Flaminio obelisk that Augustus brought to Rome alongside the Montecitorio obelisk was erected on the spina (a row of monuments in the centre of the track) of the Circus Maximus. Here, the obelisk represented the sun and the Circus Maximus was the universe, as outlined by Charax of Pergamon (fr. 34) in the second century AD, and Tertullian even viewed chariots racing around the obelisk as a cosmological metaphor (De spect. 9), with each of the colours worn by the four teams of charioteers representing a season or part of the cosmos. As a result, the tradition of paired obelisks linked these obelisks in a display of Roman power: the Montecitorio obelisk, at the centre of the Horologium Augusti, represented time, whilst the Flaminio obelisk at the centre of the Circus Maximus represented space. Both obelisks were brought from Egypt and displayed at Rome, demonstrating Roman power over both space and time, encapsulated in the idea of imperium sine fine (empire without end – Virgil, Aeneid 1.279). Just as Psamtik II had used obelisks as a way of showing his control over Egypt, Augustus used obelisks to demonstrate his authority over the whole of the Roman world that he had won after defeating Mark Antony in the civil war. That an Egyptian monument was used to celebrate this was not just a reminder of Augustus’ victory over Antony and Cleopatra, but also of the extent of Rome’s empire.

Imp(erator) Caesar divi [f(ilius)] / Augustus / pontifex maximus / imp(erator) XII co(n)s(ul) XI trib(unicia) pot(estate) XIV / Aegupto in potestatem / populi Romani redact[a] / Soli donum dedit.

"Imperator Caesar Augustus, son of a god, Pontifex Maximus, hailed imperator twelve times, consul eleven times, in the fourteenth year of tribunician powers, brought Egypt back under control of the Roman people and gave this as a gift to the Sun."

Fig. 6: Detail of the inscription on the Flaminio obelisk (CIL 6.701). The base of the Montecitorio obelisk had the same inscription (CIL 6.702) (photo by author).

As I listened to the horn being blown at the foot of the obelisk in Ripon, I wondered whether midday at the Horologium Augusti would have drawn a similar crowd. Did the people watching the shadow creep across the floor of the Campus Martius realise the history behind the obelisk? Did the people around me appreciate the Egyptian and Roman contexts of obelisks? How did the arrival of an obelisk in Rome over 2000 years ago lead to me looking at an obelisk in a market square in North Yorkshire? Maybe, I realised, there was more to be learned from the post-Augustan history of the Montecitorio obelisk. To be continued…

CIL = Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

Primary Sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus, History, Vol. I: Books 14-19, ed. and trans. J.C. Rolfe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950).

Charax of Pergamon, Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, Part II, ed. F. Jacoby (Leiden: Brill, 1926).

Isidorus, The Etymologies of Isidorus of Seville, trans. S.A. Barney, W.J. Lewis, J.A. Beach, and O. Berghof (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Vol. X: Books 36-37, ed. and trans. D.E. Eichholz (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, ed. and trans. D.W. Roller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Tertullian, Minucius Felix, Apology. De Spectaculis. Minucius Felix: Octavius, ed. and trans. T.R. Glover, G.H. Rendall (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

Secondary Sources:

Brier, B. (2016) Cleopatra’s Needles: The Lost Obelisks of Egypt (London: Bloomsbury).

Buchner, E. (1997) ‘Horologium Augusti’ in Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, Vol. 3: H-O, ed. E.M. Steinby (Rome: Quasar) 35-7.

Claridge, A. (2010, 2nd edn) Rome: An Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Curran, B. A.; Grafton, A.; Long, P. O.; Weiss, B. (2009) Obelisk: A History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Davies, P.J.E. (2000) Death and the Emperor: Imperial Funerary Monuments from Augustus to Marcus Aurelius (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Favro, D. (2005) ‘Making Rome a World City’ in The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus, ed. K. Galinsky (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 234-263.

Grenier, J.-C. (1997) ‘Obeliscus Augusti: Circus Maximus’ in Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae, Vol. 3: H-O, ed. E.M. Steinby (Rome: Quasar) 355-6.

Heath, T.L. (2014) A History of Greek Mathematics, Vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres).

Humphrey, J.H. (1986) Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

Rehak, P. (2006) Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press).

Sorek, S. (2010) The Emperors’ Needles: Egyptian Obelisks and Rome (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press).

Swetnam-Burland, M. (2010). ‘Aegyptus Redacta: The Egyptian Obelisk in the Augustan Campus Martius’, The Art Bulletin 92(3), 135-153.

(2015) Egypt in Italy: Visions of Egypt in Roman Imperial Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Vogel, L. (1973) The Column of Antoninus Pius (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Wirsching, A. (2000) ‘How obelisks reached Rome: evidence of Roman double-ships’, The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 29.2: 273-28.

This article was written by Chris Parr, a second-year PhD student in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick, funded by Midlands4Cities. Chris’ research interests are the ancient built environment of the city of Rome, particularly Rome’s fora, and the experiences of different social groups in these spaces.

The Cirencester Cockerel, by Sue Walker

The cockerel is strongly associated with the god Mercury, a connection stemming from his role as messenger to the gods, and that of the cockerel as the announcer of the dawn. Whilst many small cockerel figurines, and enamelled cockerel brooches, are known from across the northwestern provinces of the Roman empire, there are presently only ten surviving enamelled copper alloy cockerel statuettes. A recent visit to the Corinium Museum, which houses one of the most complete examples, prompted me to learn more about this unique group of figurines.

Fig. 1: The Cirencester Cockerel (image courtesy of Cotswold Archaeology Ltd.).

The Cirencester figurine (Fig. 1) was discovered as part of an excavation of the Western Roman Cemetery which revealed a total of 118 inhumation (including the grave which contained the figurine) and eight cremation burials. Nine of these burials were distinguished not only by being placed within a walled cemetery, but also by their pottery assemblage which had a clear emphasis on amphorae, flagons and tazze (ceramic vessels of incense burning) which are indicative of funerary rites involving the consumption of wine, or the pouring of libations, and the burning of incense.

Fig. 2: Burial 1163, the western cemetery of Roman Cirencester.(Image courtesy of Cotswold Archaeology Ltd.).

Fig. 3: The cockerel figurine after excavation and before cleaning and restoration of the enamel. Note the tail section was recovered from the grave fill separately. (Image courtesy of Cotswold Archaeology Ltd.).

Just outside the walled cemetery was grave GR 1163, which contained the remains of an infant aged around 2–3 years. The burial included a coffin, a ceramic feeding cup (or 'tettine'), and a cockerel figurine positioned upright beyond the head (refer to Figs. 2 and 3). The grave also contained five further sherds of pottery which suggested a date in the late first to early second century CE. It is tempting to associate the presence of a cockerel figurine in the grave of a child with Mercury’s role in accompanying the souls of the recently dead to the afterlife – and thus an expression of a bereaved parent’s concern to ensure a safe journey for the child in the afterlife.

The Cirencester figurine stands 125mm high, and the breast, wings, eyes, and ‘comb’ are inlaid with enamel, which now appears blue and green. The beak is open, in the act of crowing. The copper alloy body of the cockerel is hollow; the wing plate and tail are made separately and soldered into place (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: The construction and colour of the Cirencester cockerel. (Image courtesy of Cotswold Archaeology Ltd.)

Presently five similar figurines are known from Britain, including examples from the Royal Exchange in London, Cople in Bedfordshire (SOM-745EA2), Slyne-with-Hest in Lancashire (LANCUM-361F75), and Drayton Bassett in Staffordshire (WMID-D965B4). Other British examples include unpublished fragments from Corbridge (Corbridge Museum Acc. No 833) and Leicester (Acc. No. A116.1992.295). Continental examples include two from the Netherlands at Ezinge and Buchten (Fig. 5), and one from Belgium (Tongeren). One originated in Cologne (Fig. 5) and is now in Bonn. Additional figurines may exist solely as separated tail sections; for instance, one such example from Balkerne Lane (Colchester, Essex) was found at a site linked to the cult of Mercury. Another possible cockerel figurine was discovered in 1870 at Cirencester, but this has since been lost.

Fig. 5: Two comparative examples of cockerel figurines with the Cirencester cockerel in the centre (image credit as before). Left: bronze cockerel from Cologne, held at Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn (Image: Jürgen Vogel. LVR – Landesmuseum Bonn). Right: bronze cockerel from Buchten, the Netherlands, complete with base and inscription. (Image courtesy of the Limburgs Museum Venlo, The Netherlands).

Besides the Cirencester example, only two figures of this type have known contexts, and both of these are from the Netherlands; one was also found in a burial context (from Ezinge) whilst the other is from a sanctuary at Buchten. The function of these figurines is still uncertain. Menzel (1986, p. 60) recognised that their attribution as incense lamps or burners was improbable, at least for examples where the wing and body portions were fixed in place by soldering (as in the Cologne and London examples.) The identification of these objects as containers for incense, essences, or spices is also improbable—particularly if it is accepted that they all originally featured a tail section, which would render them closed. Therefore, a function other than simply as a decorative figurine appears improbable. Given the object's cultic associations, its use as a portable item for ceremonial activities or votive offerings appears highly plausible. This is confirmed by the Butchen example which retains its pedestal, and this carries an inscription revealing that the figurine was dedicated to an obscure goddess - Arcanua - by Ulpius Verinus, a veteran of the VI Legion.

The majority of the figurines seem to have been cast in the same way: a separate pedestal, a body in a single piece, a tail that slots into the back, and a removable wing section. However, the examples from London and Cologne both have their wings soldered onto the bodies, and it is possible these examples may have been cast without tails. The London example is further set apart from the main group by its decorative scheme, which has enamel crescents on the chest and back. Stylistically the extant figurines can be divided into two groups: those where the chest pattern is a slanting chequerboard (Cologne, Buchten and Cirencester) and those where the chest pattern is made up of many little triangles with rounded angles (Cople, Bedforshire Slyne-with-Hest and Tongeren), suggestive of separate centres of manufacture.

Indeed, the examples from Tongeren and Slyne-with-Hest (LANCUM-361F75) shown in Fig. 6 below exhibit such similarities in size and decoration that they probably originate from the same workshop.

Fig. 6: The cast copper alloy cockerel shaped vessel from Slyne-with-Hest (LANCUM-361F75). (Image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Rhineland and the area of central Belgium are acknowledged as centres of copper alloy and enamel working, and the recovery of four of the known examples from this region might support an origin in this area. However, it is now clear that Britain was also an important production centre for richly enamelled bronzes, the best known of which are the enamelled pans inscribed with the names of the forts on Hadrian's Wall. The discovery of a mould for the vessels with complete enamel decoration at Castleford (West Yorks) has lent weight to the suggestion that northern Britain was an important production centre for vessels with complex enamelled decoration. Further, two of the five known British examples of cockerel figurines are from the North of Britain, pointing to a manufacture in this area. If, as seems likely, the figurines were manufactured in Britain, the examples from the Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany may represent rare evidence of reciprocal trade between Britain and the Rhineland, extending as far as the Maas Valley. Cultural or religious preferences, reflected in the terracotta vessels (tazze) known from the graves, may be a further reason for the seeming popularity of these figurines in this area. It is however tempting to suggest that the Buchten example may have arrived as a personal possession as its dedicator, Ulpinus Varinus, was a veteran of legion VI Victrix, who was plausibly recruited when the legion was stationed at Xanten in lower Germany. The transfer of this legion to York around 120–122 CE, could indicate that the figurine was obtained in Britain, and subsequently dedicated to a local deity upon Ulpinus Varinus' return to his homeland. This hypothesis, supported by the standard 25-year term of service for a legionary, further refines the dating of cockerel figurines of this type, situating their production in the second quarter of the second century CE.

In conclusion, these figurines make up a rare group of beautiful decorative statuettes that were intended for private use, as precious objects of display. Given the link between Mercury and the afterworld, the placement of a cockerel statuette in a child's grave has an apotropaic value: becoming an expression of a bereaved parent's concern to ensure a safe journey for the child in the afterlife. Whether the figurines were manufactured in Britain or on the continent remains uncertain, as to date no moulds have been recovered. However, the figurines do represent the floruit of Roman bronze enamel working, which seems to have been short-lived, coming to an abrupt halt during the first part of the third century when the raids by Germanic tribes from across the Limes increased.

Bayley, J. (1998) ‘Spoon and vessel moulds from Castleford. Yorkshire’ in S. T. A. M. Mols (ed.) 'Ancient Bronzes. Acta of the 12th International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, Nijmegen 1992’ Nederlandse Archaeologische Rapporten, 18, pp. 105-111.

Breeze, D. J. (2012), The First Souvenirs; Enamelled Vessels from Hadrian’s wall (Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society).

Bloemers, J. H. F. (1977) ‘Archaeologishe Kroniek van Limburg over de jaren 1975-1976’, Societé Historique Archéologique Limbourg, 113, pp. 7-33.

Church, A. H. (1922) A Guide to the Museum of Roman Remains at Cirencester, 11th edition (Cirencester, Cirencester Newspaper Co. Ltd.).

Crummy, N. (2006) ‘Worshipping Mercury on Balkerne Hill, Colchester’ in P. Ottaway (ed.) A Victory Celebration: Papers on the Archaeology of Colchester and Late Iron Age Roman Britain, Presented to Philip Crummy (Colchester, Colchester Archaeological Trust) pp. 55-68.

Crummy, N. (2007) ‘Brooches and the Cult of Mercury’, Britannia 38, pp. 225-30.

Derks, T. and de Fraiture, B. (2015) Ein Romeins heiligdom en een vroegmiddeleeuws grafveld bij Buchten (Amersfoort, Reportage Archaeologische Monumentenzorg).

De Schaetzen, P. and Vanderhoeven, M. (1956) ‘De Romeinse lampen in Tongeren’, Het Oude Land van Loon, 9, pp. 5-31.

Faider-Feytmans, G. (1979) Les bronze Romains de Belgique (Mainz am Rhein, Von Zabern).

Hilts, C. (2013) 'Corinium’s Dead: Excavating Cirencester’s Tetbury Road Roman Cemetery', Current Archaeology, 281, pp. 28–34.

Holbrook, N., Wright, J., McSloy, E. R. and Gerber, J. (2017) The Western Cemetery of Roman Cirencester, Excavations at the Former Bridges Garage Tetbury Road, Cirencester 2011-2015, Cirencester Excavations VII (Cirencester, Cotswold Archaeology).

Hoss, S., Kempkens, J. and Lupak, T. (2015) ‘Bronzen beeldje van een haan met voetstuk’ in T. Derks and B. de Fraiture (eds.) Ein Romeins heiligdom en een vroegmiddeleeuws grafveld bij Buchten (Amersfoort, Reportage Archaeologische Monumentenzorg)

pp. 159-71.

Gowland, R. (2001) ‘Playing dead: implications of mortuary evidence for the social construction of childhood in Roman Britain’ in G. Davies, A. Gardner and K. Lockyear (eds) TRAC 2000: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference London 2000 (Oxford, Oxbow Books) pp. 152-168.

Künzl, E (2012) ‘Enamelled Vessels of Roman Britain’ in D. Breeze (ed.) The First Souvenirs; Enamelled Vessels from Hadrian’s Wall (Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society) pp. 9-22.

Menzel, H. (1986) Die römischen Bronzen aus Deutschland III (Mainz, Philipp von Zabern).

Pearce, J. (2015) ‘Urban exits: the contribution of commercial archaeology to the study of death rituals and the dead in the towns of Roman Britain’ in M. Fulford and N. Holbrook (eds.) The Towns of Roman Britain: the contribution of commercial archaeology since 1990, Britannia Monograph Series 27, (London, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) pp. 138-66.

Philpott, R. A. (1991) Burial Practices in Roman Britain: A survey of grave treatment and furnishing, A.D 43-410 (Oxford, Tempus Reparatum).

Smith, R. A. (1922) A Guide to the Antiquities of Roman Britain in the Department of the British and Medieval Antiquities (London Trustees of the British Museum).

Toynbee, J. M. C. (1971) Death and Burial in the Roman World (London, Thames and Hudson).

Worrell, S. (2006) Roman Britain in 2005 (II Finds reported under the portable Antiquities Scheme) (London, The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies) pp. 426-7.

Worrell, S. (2012), Enamelled vessels, and related objects reported to the Portable Antiquities scheme 1997-2010 Kendal, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society) pp. 81-82.

Zadoks-Josephus Jitta, A. N., Peters, W. J. T. and Van Es, W. A. (1967) Roman Bronze Statuettes from the Netherlands, Vols I and II (Wolters- Noordhoff, Scripta Archaeologica Groningana 1 and 2).

Sue is a final year PhD candidate in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Warwick. Her research explores the deposition of coinage on Romano British sanctuary sites, with a particular emphasis on imitation coinage. She is an experienced archaeologist, who has worked on deeply stratified urban sites and large scale open area excavations. She has an interest in small archaeological finds, particularly Iron Age and Romano-British brooches, figurines and coins.

How Were the Romans Connected by Death? A Sarcophagus in the Uffizi, by Rose Su

The recent launch of the hit video game Death Stranding 2 has reshaped how we imagine death and the afterlife. In this fictional world, the dead do not simply vanish; instead, they become “Beached Things” — spectral figures trapped in a liminal space called a “Beach”, suspended between the living and the dead. The concept of liminality immediately resonated with me, as Roman sarcophagi are often understood as liminal objects themselves, or at least as possessing a distinct degree of liminality. Like the “Beach”, the sarcophagus marks a threshold: the dead enclosed within, the living remaining outside. What makes the comparison even more compelling is that, in the game, each person typically possesses a “Beach” of their own — yet those with deep emotional ties might end up sharing the same one. Similarly, in antiquity, sarcophagi were sometimes reused or adapted to accommodate more than one individual, connecting lives that may never have overlapped in life, but now rest together in death. Now, the question is: how did these Romans come to share the same casket? For a sarcophagus depicted with scenes drawn from the life of Roman elite culture, now displayed in the Uffizi, Florence, the reuse might not be simply motivated by familial connections, but perhaps by being drawn to the images and values depicted on the sarcophagus. In this sense, the sarcophagus does not just hold bodies, but becomes a site of posthumous connection through shared ideals.

Fig. 1: The front panel of the sarcophagus showing the scenes of Vita Romana. Florence, the Uffizi inv. 1914 n. 82. Photo: By Tao Yu, 29/05/2025.

The sarcophagus, decorated on the front and the two side panels (Figs. 1-3), represents the typical sarcophagi produced in the city of Rome or nearby. As one of the canonical sarcophagi depicted with the scenes of Vita Romana (scenes drawn from the real life of Roman elite culture), the front panel consists of three scenes from left to right (Fig. 1). At the very left corner, we find two charging horsemen over a boar and two hunting dogs. A comparison with another contemporary sarcophagus now in the Los Angeles County Museum (inv. 47.8.9) shows that this hunting scene derived from a battle scene depicted with two barbarians below the horsemen. Then, a male in a sleeved tunic who bears a portrait feature stands in front of a woman who is bending over and pushing a pleading boy. Another male figure is standing behind the woman. Notably, this scene, likely inspired by similar depictions from the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, exemplifies the Roman virtue of clementia (mercy, clemency) – from the victorious general to the barbarians. Next, the middle part of the front panel features a man with a portrait making a sacrifice in front of a temple. A bull is featured next to the altar, and a man behind is ready to kill the sacrificial bull with an axe. The scene of making a sacrifice exemplifies the Roman virtue of pietas, that is, the devotion and duty to the state. Finally, the man bearing the portrait, though this time in a toga, appears the third time at the marriage scene on the right of the front panel. The man is holding hands with a woman whose face is covered by a veil. Their posture, dextrarum iunctio, joining of the right hands, and the personification of concordia behind them state the Roman ideal of marital harmony, concordia, as a civic and moral virtue.

This sarcophagus was reworked in antiquity as these Severan portrait heads contradict its original production date, c. 180 CE. It is possible that the second owner was the son of the original one, and that family succession played a role in the reuse of the casket. However, it is equally important to consider that the Roman virtues embedded in the sarcophagus decorations themselves likely contributed significantly to the decision of reuse.

To better understand the reuse, we must first recognise that although these scenes were often inspired by real events, they do not necessarily imply that the individuals buried within actually experienced them, particularly the first two scenes. These two scenes typically involved only a few top-ranked individuals in the Roman society. Perhaps this could explain the reworking of what was originally a battle scene into a hunting scene, which might better reflect the civic status of the second owner. Indeed, a closer examination of the three portraits reveals age differences: the central figure appears youngest, the right one middle-aged, and the left most mature. These portraits, and the events they attend, do not seem to follow any certain chronology. Rather, these events and the virtues they imply hold greater significance.

Fig. 2: The left side panel of the sarcophagus showing the scenes of Vita Romana. Florence, the Uffizi inv. 1914 n. 82. Photo: By Tao Yu, 29/05/2025.

Fig. 3: The right side panel of the sarcophagus showing the scenes of Vita Romana. Florence, the Uffizi inv. 1914 n. 82. Photo: By Tao Yu, 29/05/2025.

The side panels could reinforce our understanding above. The left panel (Fig. 2) features a bearded figure getting ready, possibly for battle. His bearded appearance is markedly different from the portraits on the front panel, suggesting that this figure was not intended to correspond with any of the male figures on the front, but rather to evoke the connection with the original battle scene. On the right panel (Fig. 3), we find scenes of the upbringing and education of children, with the Fates featured behind, pointing at a globe and holding books in their hands. A young man holding a theatrical mask in his hand stands in the right corner. Again, the absence of portrait features implies that this scene does not resonate with any specific moment, but rather the continuation of the marriage and the exemplary values of Roman domestic life.

In conclusion, while we cannot exclude the possibility that this sarcophagus was reused by members of the same family, particularly given the high cost of such objects, there is a compelling reason to look beyond practicality. The carved reliefs and the virtues they embody offer a deeper explanation for the casket’s reuse. Like those “Beached Things” with strong emotional ties that end up in the same “Beach”, the Romans had chosen to be buried together due to shared aspirations of Roman moral ideals. Although Roman beliefs surrounding the afterlife were complex and often considered without a single doctrine, this sarcophagus, through its persistent illustration of Roman virtues, offers a vivid example of how death functioned not only as a separation but also as a point of connection among individuals over time.

Amedick, R. (1991) Sarkophage mit Darstellungen aus dem Menschenleben: Vita Privata. ASR 1, 4. (Berlin: Mann).

Birk, S. (2013) Depicting the Dead: Self-Representation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits. (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press).

Borg, B.E. (2018) ‘No One is Immortal: From Exemplum Mortalitatis to Exemplum Virtutis’, in Audley-Miller, L.G. and Dignas, B. (eds.) Wandering Myths: Transcultural Uses of Myth in the Ancient World. (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 169–208.

Gallerie degli Uffizi: Sarcophagus with scenes from the Vita Humana et Militaris. Available at: https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/sarcophagus-scenes-vita-humana-et-militaris (Accessed: 4 July 2025).

Platt, V. (2012) ‘Framing the Dead on Roman Sarcophagi’, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 61/62, pp. 213–227.

Platt, V. (2017) ‘Framing the Dead on Roman Sarcophagi’, in Platt, V. and Squire, M. (eds.) The Frame in Greek and Roman Art: A Cultural History. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 353–381.

Russell, B. (2011) ‘The Roman Sarcophagus “Industry”: A Reconsideration’, in Elsner, J. and Huskinson, J. (eds.) Life, Death and Representation: Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi. (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 301–340.

Russell, B. (2013) The Economics of the Roman Stone Trade. Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Rose is a PhD candidate in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her research interests are Roman sarcophagi and Mediterranean archaeology.

Roman sailors in Australia? Discovering the Roman navy from the Nicholson epigraphic collection of the University of Sydney, by Ludovico Bevilacqua

Did ancient Roman sailors ever make it to Australia? Well, their funerary monuments certainly did in the nineteenth century, and today they offer a fascinating window into the Roman navy and the lives of those who served in it. The Nicholson epigraphic collection of the University of Sydney consists of 68 funerary inscriptions, 63 of which are written in Latin and 5 in Greek. Today these are displayed at the Chau Chak Wing Museum of the University of Sydney, New South Wales (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: The current display of part of the Nicholson epigraphic collection at the Chau Chak Wing Museum. Author's own image.

Almost all the inscriptions were collected by Sir Charles Nicholson (1808-1903), the English founder of the University of Sydney (1850), during two trips which he made through Italy between 1857 and 1858. These travels are testified by his original Passport, today kept in the Archives of the University of Sydney, and the analysis of it allows us to reconstruct where he acquired the objects (Fig. 2). In 1860, at the time when he was University Provost, Nicholson donated his inscriptions to the institution, together with hundreds of other ancient objects. His aim was to establish the first Australian Museum of Antiquities, which became known worldwide as the Nicholson Museum, recently transferred into the new Chau Chak Wing Museum.

Fig. 2: The original passport of Sir Charles Nicholson, from the Archives of the University of Sydney. Author's own image.

The Nicholson epigraphic collection, for the most part, was collected from Rome and the surrounding countryside and the territory of the Campi Flegrei near Naples. In particular, 7 inscribed plaques, almost all of which came from Campania, deal with sailors of one of the two ancient Roman fleets, the classis praetoria Misenensis, whose headquarters were located, not by chance, in the ancient city of Misenum (Miseno), close to Naples. In this context, the funerary inscriptions related to seamen of the Roman fleet appear to be characterised by some common features, which we can easily recognise in the objects from the Nicholson collection. They are generally carved on rectangular white marble plaques, sometimes re-used, with irregular sides and have no decoration. Although not all of the plaques contain explicit references to the fleet in their text, they almost all indicate at least the name of the ship on which the deceased or the dedicator served, confirming that they were actually seamen. Most of them clarify the age of the deceased (vixit annis no), often accompanied by his years of service in the fleet (militavit annis no), and his role on board (e.g. manipularis). In half of the cases, the text records the sailor’s heritage, expressed through the term natio, and the typology and name of the ship where he served (e.g. ex III [3 = trireme] Fide]. In particular, while the details related to the age of the deceased seem to have usually been approximated to multiples of 5, as in the ancient world it was hard to deal with this information with precision, the references to the years of service are considered to be reliable, as they were carefully recorded in the Roman army (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Inscription NMR.1084 (AE 1949, 208). Image: Chau Chak Wing Museum website.

D(is) M(anibus).

C(aio) Iulio Reso, manip(ulario)

ex I̅I̅I̅ Fide, nat(ione) Bess(o),

(scil. qui) bixit (!) an(nis) LV, milit(avit) a(nnis) XII,

5 M(arcus) Rufinus Auctus,

heres, b(ene) m(erenti) f(ecit).

“To the Spirits of the Underworld. For the well-deserving Caius Iulius Resus, manipularius from the triremis Fides, Bessus, who lived 55 years, joined the army for 12 years, Marcus Rufinus Auctus, heir, commissioned”.

At the beginning of the Principate of Octavian, after the battle of Actium in 31 BC, a new military port for the Roman fleet was built under the supervision of Agrippa at the Campanian promontory of Miseno. The aim was to substitute a previous structure which had been built during the war against Sextus Pompey in the Tyrrhenian Sea but had rapidly become unusable for natural causes, the portus Iulius near Pozzuoli. The new port was built inside two natural basins and, alongside Ravenna on the Adriatic Sea, became the main naval base of the Roman fleet for the following centuries in which it dominated the Mediterranean. The port also contributed to the development of the city of Miseno, that was then made independent from the administration of Cuma. During the centuries of its activity, the fleet of Miseno consisted of at least one hexeris (ship with six banks of oars), one penteris (five) and various quadriremes (four), triremes (three) and liburnae (two), on the basis of their dimensions. The Roman sailors, who were at the same time the soldiers and the rowers of the ships, were subordinated to a military hierarchy which was similar to the one of land troops: they were called milites or manipulares (“soldiers”), not nautae (“sailors”), and had different roles according to their function on board, divided between soldiers, technicians, sub-officers and officers (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Inscription NMR.1125 (AE 1949, 206). Image: Chau Chak Wing Museum website.

Dis Manibus.

C(aio) Gentio Valenti, militi

ex classe praetoria Mise=

nense (!) ex I̅I̅I̅I̅ Miner(va), natiọṇ(e)

5 Dalm(atae), (scil. qui) vix(it) ann(is) XL, in his mil(itavit) anṇ(is)

XIX, heredes bene merito

Tonatius Sever(us) et Mettius Seṿẹ(rus) (scil. fecerunt).

“To the Spirits of the Underworld. For the well-deserving Caius Gentius Valens, soldier of the Praetorian fleet of Miseno, from the quadriremis Minerva, Dalmatian, who lived 40 years, joined the army for 19 years, the heirs Tonatius Severus and Mettius Severus commissioned”.

From the time of Vespasian to that of Septimius Severus, the term of military service on the ships, the longest and the least prestigious of the Roman army, lasted 26 years, and was then raised to 28 years. The seamen’s age of enlistment was usually between 18 and 23 years old, but they could also voluntarily join the navy when they were older. Sailors were usually enlisted among peregrini (foreign non-citizens who were however freeborn) from a variety of different areas of the Mediterranean. They often specified their heritage on documents related to them, such as funerary inscriptions and military diplomas, using the formula “natione + a geographical adjective”. According to the surviving sources it seems that, in the case of Miseno, the favourite enrolment areas were Egypt and Thrace, the latter especially from theThracian “Bessi” people, where the majority of the milites came from (Fig. 5).

As is commonly believed by scholars, under the rule of Vespasian the fleet was given the name of praetoria. Probably in relation to this occurrence, from the end of the first century AD sailors, from the moment of their enlistment, replaced their original foreign names as peregrini with a new Roman one, made up of three Latin names (tria nomina – first name, family name and nickname), like all the Roman citizens. The sailors either chose their new denomination on their own or were given it by the fleet’s officers. This resulted in a striking variety of seamen’s names in Miseno and Ravenna, even though a few common habits can be recognised. In particular, the new family names were usually chosen among widespread Roman names(e.g. Iulius, Fig. 3), which could be referred to former Emperors or to officers and fellow soldiers of the fleet. On the other side, the new nicknames generally came from the sailors’ original non-Latin names (e.g. Buccio, Fig. 5) or from a traditional collection of Roman epithets, especially the ones referred to moral or physical qualities(e.g. Valens, Severus) (Fig. 4).

As confirmed by epigraphic sources, during the years spent in the navy, seamen created common law families with their partners, who were often freedwomen or daughters of fellow soldiers, and had children and sometimes owned slaves and freedmen. Apart from these relationships, it seems that the manipulares of the fleet during their service did not integrate much into society at Miseno and created, instead, a separate community of sailors. Most of the references to people from outside the milites’ families found on funerary inscriptions are linked to other members of the fleet, who had usually been appointed as heirs of the deceased. Indeed, it was customary for seamen to nominate their heirs among their fellows, often exclusively, making them responsible for their belongings, burial and gravestone, and for the safeguard of their not legally recognised families, in case of sudden death during service (Fig. 3).

At the end of their conscription, through the honesta missio (“honourable discharge”) veterans obtained full Roman citizenship and their eventual common-law marriages were officially recognised. Most of them, as it is possible to learn from the inscriptions related to sailors who explicitly presented themselves as veterans, remained at Miseno or in the surrounding area, where they generally started commercial or agricultural activities, finally integrating into society in the city. A few people continued serving past their required term of service, probably because of their experience in specific technical roles (Fig. 5). The habit of definitively settling in the urban centre where they had served was mainly favoured by the existence of a collegium (corporation) which reunited all the navy veterans at Miseno. That represented an occasion for them to take part in the social and political life of the city and to gain social promotion for themselves and their descendants, who sometimes even entered the ordo decurionum (the ruling class of the city).

Fig. 5: Inscription NMR.1097 (CIL X 3602; AE 1949, 209b). Image: Chau Chak Wing Museum website.

D(is) (vac.) M(anibus).

M(arco) Mario Cel=

so, man(ipulario) (scil. ex) I̅I̅I̅ Athe=

nonice, nat(ione) Bess(o),

5 (scil. qui) vịx̣(it) ạnn(is) XLV, mil(itavit)

aṇṇ(is) (vac.?) X̣XXVII, L(ucius) Va=

lepiuṣ (!) (vac.) Bucci(o)

mereṇ(ti) (vac.) fecit.

“To the Spirits of the Underworld. For the deserving Marcus Marius Celsus, manipularius from the triremis Athenonice, Bessus, who lived 45 years and joined the army for 37 years, Lucius Valerius Buccio commissioned”.

In conclusion, despite their nineteenth-century transfer to the other side of the world, the ancient inscriptions from the former Nicholson Collection remain a paramount source for our understanding of the Roman past. Above all, the group of seven funerary plaques relating to sailors from Campania, almost all on display at the Chau Chak Wing Museum of the University of Sydney, Level 2, significantly enhances our understanding of the organisation of the Roman navy and the lives of the men who served in it.

Bibliography

AE = L'année épigraphique, 1888-.

CIL = Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum, Berlin 1863-.

Bevilacqua, L. (2022) The Nicholson Epigraphic Collection of the University of Sydney, MA Thesis, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, a.y. 2021/2022.

Chau Chak Wing Museum Website, Collections search, Nicholson's epigraphic collection: https://www.sydney.edu.au/museums/collections_search/?record=enarratives.980.

Chioffi, L. (2013) ‘Portus Iulius. Un porto militare?’, Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Antiquité 125.1.

Fitzhardinge, L.F. (1951) ‘Naval Epitaphs from Misenum in the Nicholson Museum, Sydney’, The Journal of Roman Studies 41:17-21.

Forni, G. (1979) ‘L’anagrafia del soldato e del veterano’, in Actes du VII° Congrès International d’Épigraphie Grecque et Latine, Pippidi, D.M. (ed.), Conference proceedings (Bucaresti – Paris) 205-28.

Parma, A. (1992) ‘Osservazioni sul patrimonio epigrafico flegreo con particolare riguardo a Misenum’, in Civiltà dei Campi Flegrei. Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Gigante, M. (ed.), Conference proceedings (Napoli) 215-7.

Parma, A. (1994) ‘Classiari, veterani e società cittadina a Misenum’, Ostraka 3.1: 43-59.

Parma, A. (1999) ‘Per una tipologia delle iscrizioni funerarie dei classiari misenati’, in Atti del XI Congresso Internazionale di Epigrafia Greca e Latina, Conference proceedings (Roma) 1, 817-24.

Parma, A. (2002) ‘Note sull’origine geografica dei classiari nelle flotte imperiali: i marinai di provenienza nordafricana’, in L’Africa romana, 14. Lo spazio marittimo del Mediterraneo occidentale: geografia storica ed economica, Khanoussi, M. - Ruggeri, P. - Vismara, C. (eds), Conference proceedings (Roma) 323-32.

Parma, A. (2017) ‘Nuovi dati su società cittadina e classiari a Misenum: prime note’, in Colonie e municipi nell’era digitale. Documentazione epigrafica per la conoscenza delle città antiche, Antolini, S. - Marengo, S.M. - Paci, G. (eds), Conference proceedings (Tivoli, Roma) 459-72.

Passport of Nicholson, containing visas to a number of European countries, University of Sydney Archives, Personal Archives of Sir Charles Nicholson, Group P.4, Series 2, Item 2.

Reddè, M. (1986) Mare nostrum: les infrastructures, le dispositif et l'histoire de la marine militaire sous l'Empire romain (Rome).

Reeve, E. (1870) Catalogue of the Museum of Antiquities of Sydney University (Sydney).

Salomies, O. (1996) ‘Observations on some names of sailors serving in the fleets at Misenum and Ravenna’, Arctos 30:167-86.

Starr, C. (1960, 2nd edition) The Roman imperial navy (Cambridge).

Trendall, A.D. (1948, 2nd edition) Handbook to the Nicholson Museum (Sydney).

This article was written by Ludovico M. Bevilacqua, a second year PhD candidate in Classics and Ancient History at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice (Italy), in co-tutelle with the University of Warwick, where he is spending the current academic year. His doctoral research focuses on the history of the Maffeiano Lapidary Museum of Verona (Italy), the first public epigraphic collection entirely dedicated to ancient inscriptions, and of its creator, Scipione Maffei (1675-1755). His interests include the reception and collection of ancient inscriptions within the broader history of Classical scholarship.

Beauty and the Beast: Polyphemus and Galatea, a love story? by Elena Claudi and Jacqui Butler

What first springs to mind when you think of Polyphemus? Most likely it is the monstrous one-eyed Cyclops, the Homeric ogre who imprisoned Odysseus and his men in his cave, devouring them one by one (Homer, Odyssey 9.116-566). This is certainly how he is first represented in archaic art; scenes of his blinding by Odysseus are a recurrent theme on Greek vases (Fig. 1). However, despite this being a key part of his characterisation, there is more to Polyphemus’ depiction in surviving Greek and Roman literature and art than simply a one-eyed, man-eating monster. This article explores the lesser-known love story between Polyphemus and the Nereid (sea nymph) Galatea which appears in both literary sources and frescoes from Pompeii and surrounding sites in Campania.

Fig. 1: The blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus and his men, on a Laconian cup dated to ca. 550 BCE. Paris, Cabinet des Medailles, No. 190. Image: Bibi Saint Pol, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

One of the earliest sources (4th-3rd century BCE) that tells us of the love between Polyphemus and Galatea is Theocritus in his Idylls 6 and 11. The former describes a bucolic competition between the two oxherds Daphnis and Damoetas who perform two contraposed songs: the first one is addressed to Polyphemus and describes the fickle nature of Galatea; the second song is performed by Damoetas, who acts the part of Polyphemus. The Cyclops tries to arouse Galatea’s interest by ignoring her and praising his own beauty: “The other day, when there was a calm, I was looking into the sea, and in my judgment my beard seemed fair, and fair my single eye, and it reflected the gleam of my teeth whiter than Parian marble” (Theoc. Id. 6.35-38, trad. N. Hopkinson).

A similar illusion – grotesque and comic – characterises Polyphemus’ song in Idyll 11: although he is aware of his unattractive physical appearance, the Cyclops tries to seduce Galatea, but then realises that the Nereid will not reciprocate and, while talking to himself, expresses his resentment: “why do you pursue someone who flees? Maybe you’ll find another Galatea who is even prettier. Many girls invite me to play with them through the night, and they all giggle when I take notice. It’s clear that on land I too am a somebody.” (Theoc. Id. 11.75-79, trad. N. Hopkinson). Idyll 11 represents a naive and clumsy Cyclops who arouses our sympathy for him. The contrast between the roughness of Polyphemus and the beauty of Galatea creates a tragicomic distance between the “beauty” and the “beast” and makes us question whether the giggles of the many girls who invite the Cyclops to play are meant to seduce or mock him.

Among the Latin sources, Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1st century BCE-1st century CE) is the text that narrates more extensively the myth of Polyphemus and Galatea and proposes a different perspective, Galatea’s, as she tells Scylla the unfortunate ending of her love story in confidence. In this version, the Nereid is in love with Acis, who is transformed into a river after the jealous Polyphemus kills him with a rock. The song of Polyphemus, who tries to seduce Galatea in vain, is here quoted by Galatea and imitates Polyphemus’ song in Idyll 11. However, in contrast with Theocritus’ Idyll, in the Metamorphoses, Galatea portrays Polyphemus as a violent man whose brutal nature cannot be changed by love and whose jealousy determines the hate of the Nereid: “Nor, if you should ask me, could I tell which was stronger in me, my hate of Cyclops or my love of Acis; for both were in equal measure.” (Ov. Met. 13.756-8, trad. F. J. Miller).

Similarly, the Dialogues of the Sea-Gods 1 by Lucian, a Greek text written in the 2nd century CE, shows us a mingling of love and repulsion in the dialogue between Galatea and Doris. While Doris criticises Polyphemus’ physical appearance and behaviour realistically and bluntly, Galatea tries to overturn her friend’s observations by showing her lover in a positive light.

GALATEA

[…] But not one of you has any shepherd or sailor or boatman to admire her. Besides, Polyphemus is musical.

DORIS

You’d better not talk about that, Galatea. We heard his singing the other day, when he came serenading you. Gracious Aphrodite! Anyone would have taken it for the braying of an ass. (Lucian, Dialogues of the Sea-Gods 1.3-4, trad. M. D. MacLeod)

Polyphemus is considered from a more ruthless perspective also in the Imagines (2.18) of Philostratus (2nd-3rd century CE). This ekphrastic text describes the various paintings of a Neapolitan house; one of them portrays Polyphemus as he is singing and wooing Galatea, who, nevertheless, is in the sea, ignoring him and looking at the horizon. The Imagines point out the brutal nature of the Cyclops and his illusion of being a sweet lover, while, instead, he appears to the viewers as a beast: “He thinks, because he is in love, that his glance is gentle, but it is wild and stealthy still, like that of wild beasts subdued under the force of necessity.” (Philostr. Imag. 2.18.3, trad. A. Fairbanks).

The description of Philostratus that portrays Polyphemus singing to Galatea and looking at her from his mountain resembles the Third Style painting from the Augustan villa at Boscotrecase which dates to ca. 11 BCE (Fig. 2). It is a pastoral and idyllic scene with Polyphemus (interestingly not portrayed as a particularly large figure) sitting centrally on a rock with a flock of goats in the foreground; lovestruck, he raises his panpipes to play and woo Galatea, who sits below left on a dolphin, as her clothing billows around her in the breeze.

Fig. 2: Polyphemus and Galatea, fresco from Boscotrecase, now in The Museum of Metropolitan Art, New York, MMA 20.192.17. Image: Public Domain.

So far, so romantic; but look upward to the right of centre, and we see another figure standing on a rocky outcrop about to hurl a large rock at a departing ship. This alludes to the separate Homeric part of Polyphemus’ narrative, but also perhaps to the other more violent side of his character. The repetition of the same character in Greek and Roman art is referred to as continuous narrative, and the recurrent character usually features in several scenes, as in a frieze. Alongside this, whether the painting represents the reciprocal love between Polyphemus and Galatea, or Polyphemus’ unrequited love, is difficult to answer definitively. This uncertainty may have been part of the composition’s appeal – the viewer chose which version they understood from the painting.

Is this the same painting described in the Imagines? It is unlikely, as the paintings described by Philostratus probably did not exist (Webb, 2006). However, real paintings could have inspired Philostratus to engross his audience in his descriptions by reminding the readers or listeners of artworks they saw (Squire 2015, esp. 204, 211).

The painting from Boscotrecase is one of many from Campania which depict the Polyphemus and Galatea narrative, with approximately twenty-two known portrayals depicting different parts of their relationship. The Vesuvian eruption provides a terminus ante quem dating of 79 CE for all the frescoes, although some of the mythological Third Style paintings are dated to the first century BCE.

Most (but not all) of the surviving Polyphemus/Galatea paintings can be categorised into three different types: Polyphemus seeing or wooing Galatea who sits upon a sea creature, Eros and Polyphemus with a letter, and the couple as lovers. While the first type is best represented in the example we have just considered, the second composition depicts Eros either delivering a letter from Galatea to Polyphemus, or receiving a letter from Polyphemus to take to Galatea.

These are again generally idyllic pastoral scenes, with Polyphemus’ role as a shepherd indicated by the inclusion of a staff. The best surviving example is from Herculaneum (Fig. 3); Polyphemus is seated on a rock holding a lyre and stretching his right hand towards Eros. The ambiguity as to whether Polyphemus is giving or receiving the letter may suggest that, similar to the Boscotrecase painting, the viewer could decide what was happening. Alternatively, this composition could reflect an element of narrative which more clearly told this part of the story, perhaps a lost literary source, or another form of storytelling.

Fig. 3: Polyphemus receiving a letter from Galatea. Museo Archeologico di Napoli, Inv. 8984. Image: Carole Raddato, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 2.0.

The third composition type depicts the supposed happy outcome of Polyphemus and Galatea’s story; Appian, writing in the 2nd century CE, believed this was the most convincing version of the narrative and names their three sons Celtus, Illyrius and Galas (Appian Roman History, 9.2). In the frescoes the couple are usually shown in an intimate embrace, as seen in the painting from the Casa della Caccia Antica, Pompeii (Fig. 4). This is a sensual image; Polyphemus stands behind the mostly naked Galatea, who reaches up to embrace him as he encircles her in his arms. The viewer’s recognition of the scene is aided by the inclusion of the sheep and staff. Interestingly, a painting depicting Polyphemus wooing Galatea featured in another room in the same house. This suggests that in the context of this particular house, the paintings may have been viewed progressively, with viewers first encountering the wooing image where there is an element of tension as the outcome is uncertain, before seeing reciprocal love as the conclusion.

Fig. 4: Polyphemus and Galatea as lovers from the Casa della Caccia Antica, Pompeii, VII 4 48. Museo Archeologico di Napoli, Inv. 27687. Image: Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Appian, Roman History, Volume II (2019), edited and translated by B. McGing (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Lucian, Dialogues of the Dead. Dialogues of the Sea-Gods. Dialogues of the Gods. Dialogues of the Courtesans (1961), translated by M. D. MacLeod (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Ovid, Metamorphoses (Volume II: Books 9-15) (1916), translated by F. J. Miller; revised by G. P. Goold (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Philostratus the Elder, Imagines; Philostratus the Younger, Imagines; Callistratus, Descriptions (1931), translated by A. Fairbanks (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Theocritus, Moschus, Bion (2015), edited and translated by Neil Hopkinson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Secondary Sources:

Goldhill, S. (1988) ‘Desire and the figure of fun: glossing Theocritus 11’ in Post-Structuralist Classics, ed. A. Benjamin (London: Routledge) 79-105.

Hodske, J. (2007) Mythologische Bildthemen in den Hausern Pompejis (Ruhpolding, Franz Philipp Rutzen).

Leach, E.W. (2004) The Social Life of Painting in Ancient Rome and on The Bay of Naples (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Lorenz, K. (2015) “Wall Painting” in A Companion to Roman Art, ed. B.E. Borg (Chichester, John Wiley & Sons) pp. 252-267.

Newby, Z. (2016) Greek Myths in Roman Art and Culture Imagery, Values and Identity in Italy 50 BC-AD 250 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Shapiro, H. (1994) Myth into Art, Poet and Painter in Classical Greece (London and New York, Routledge).

Squire, M. (2009) Image and Text in Graeco-Roman Antiquity (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Squire, M. ed. (2015) Sight and the Ancient Senses (London, New York: Routledge).

Webb, R. (2006) “The Imagines as a Fictional Text: Ekphrasis, Apatē and Illusion” in Le défi de l’art: Philostrate, Callistrate et l’image sophistique, eds. Costantini, M. et al. (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes), 113-136.

Woodford, S. (2003) Images of Myth in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

This post was written by PhD candidates Elena Claudi and Jacqui Butler in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick.

Elena is a PhD candidate in the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick funded by Midlands4Cities. Her research interests are Greek ekphrasis of the imperial period and its rhetorical, artistic and sensorial dynamics.

Jacqui is in the final stages of a part-time PhD. Her research focusses on the visual representation of specific mythological characters in Roman art, contextualising these against societal ideals and potential viewer interaction.

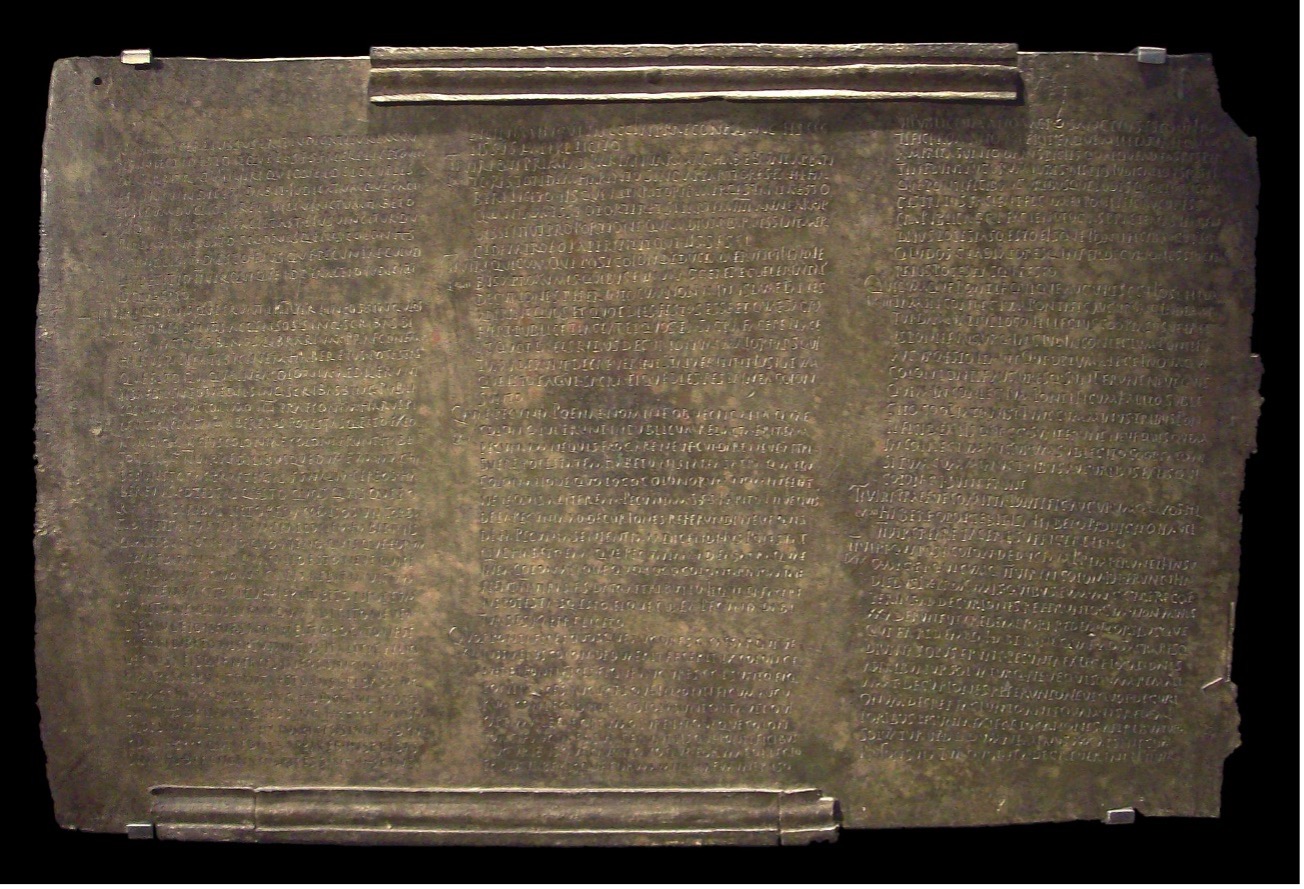

The Lex Ursonensis and the Romanisation of Baetica, by Carlos Enríquez de Salamanca

The Lex Ursonensis (CIL II2/5, 1022) [Fig. 1], the foundational charter of the colony of Urso (modern-day Osuna, Andalucía, Spain) offers a particularly good opportunity to consider the effects of Roman influence in the region and the processes traditionally considered under the term “Romanisation”. A Flavian-era (AD 69 – AD 98) copy of the charter was discovered in 1870 and is currently conserved at the Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Madrid in a series of 5 extant bronze tablets, of which we have 73 chapters that have survived, out of the original 142. These tablets measure about 59cm x 92.2cm, making them relatively large. Here, I will consider some of the phenomena that I believe are most interesting as revealed by the charter: firstly, the local elites of Baetica, traditionally seen as the spearheads of voluntary Romanisation; and secondly, the topographical changes that came with Roman colonisation/influence, which has often been seen as an extension of Romanisation. Through analysis of the charter, I hope to nuance these views and reconsider our assumptions about the effects of Roman influence.

Fig. 1: Lex Ursonenis 61-69, National Archaeological Museum, Madrid, Inv. 16736. Image: Luis García, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 3.0.

While at the very beginning of Roman presence in the area the locals were permitted to keep their own forms of government, eventually the Roman system prevailed, “effectively [eliminating] the reguli, principes, duces, and other anomalous leaders” and replacing them with local magistrates on the Roman model (Curchin 1990, 7). These local elites were thus re-organized or re-shaped into a more Romano-Italic model with the internal government now located in the ordo decurionum or local senate (Urs. 64, 96, 98, 105). The members of the local elite could now compete for political honours in the ‘Roman’ way, through a mixture of elite co-optation and community elections which required campaigning. (Rodríguez Neila 2003, 79). Election to one of the magistracies brought with it not only honour and prestige, but also (in the Latin towns) the coveted Roman citizenship.

Access to the ordo was zealously guarded by the local elites, and this was ensured both by a series of entry requirements (age, property, citizenship of local community, free birth, and good moral standing), and by the fact that membership could be revoked (Urs. 105). Furthermore, one could only join the ordo through election (creatio) or co-optation (adlectio). However, in order to be able to stand for a magistracy, membership to the ordo was required, which ensured that the municipal honours could be safely guarded and shared within the local aristocracies (Urs. 101). Furthermore, given that the decurions would conduct periodical checks on the lists of members, they could also ensure that no undesirable people joined or stayed within their ranks.

The most important political positions were those of the local magistrates, of which three stand out: quaestors, aediles, and duumvirs. Although the lex Ursonensis does not speak of quaestors, these are well attested elsewhere, and were lower in potestas (power) to the duumvirate, and possibly at the same level or lower than the aedileship, which was, at the same time, clearly lower than the duumvirs (Mal. 54; Urs. 62). The quaestorship was not always necessary before the holding of the higher magistracies, although the aedileship did seem to be the stepping stone towards the duumvirate, despite the fact that other avenues – such as religious offices – could also serve as part of an individual’s cursus (political career) (Curchin 1990, 31-32, 40). At Urso, aediles are stated to have the duties of organising shows and games in honour of the gods, overseeing the construction of local buildings and infrastructure projects, administer the accounts of the colony, or they could even be left in charge in the absence of the duumvirs (Urs. 71, 77, 81, 94, 98). Meanwhile, the duumvirs were mainly in charge of the running of the city as the leading magistrates and settling judicial matters (Urs. 61, 77, 100).

The status and prestige those magistracies and membership of the ordo brought with them was not minor. Local aristocrats invested greatly in euergetism and donations for the cities in order to join the ordo, but also to ensure that their families and descendants would gain access to it too. For instance, see the dedication made by a duumvir at Urgavo (Arjona) to the emperor Augustus in AD 11/12 (CIL II2/7, 69) or the dedication by another duumvir (elected for a second time) of Italica (Seville) marking his donation of porticoes and arches for the city’s theatre (AE 1983, 522; Luzón & Castillo 2007, 197-198). While membership to the local aristocracy was not hereditary, the ordo had the prerogative to add or remove members, so it was very important for local elites to ensure their descendant’s inclusion in order to enhance their family’s standing. This was especially the case in cities with the Latin rights, where locals could access Roman citizenship through holding local magistracies (Salp. 21). This has led some scholars to argue that Romanisation was a voluntary and enthusiastic phenomenon, spearheaded by the local elites who had much to gain. Some elites even went so far as to leave their hometown in search of further political gains in the neighbouring towns, such as M. Marcius Proculus in Córdoba [Fig. 2], thus creating what has been dubbed a supra-local elite (Melchor Gil 2011; CIL II2/5, 257).

Fig. 2: Funerary inscription dedicated to Marcia Procula by her father, M. Marcius Proculus, originally from Sucaelo but was a duumvir at Córdoba. Image: Navarro Caballero (2017) n.14.

CIL II2/5, 257:

M(arcia) M(arci) f(ilia) Procula

Patriciensis an(norum) III s(emis)

M(arcus) Marcius Gal(eria)

Proculus Patricien/sis domo Sucaeloni

IIvir c(olonorum) c(oloniae) P(atriciae).

[Here lies] Marcia Procula of Córdoba, daughter of Marcus, who lived for three and a half years. Marcus Marcius Proculus of Córdoba, member of the tribe Galeria, originally from Sucaelo, duumvir at Córdoba.

However, assumptions about the degree of Romanisation of areas conquered by Rome, often based on misleading information in the ancient sources, can, however, be too rash. A case in point is the idea of the 'replica model' of Roman colonisation (Enríquez de Salamanca 2024). Aulus Gellius wrote that “[Roman] colonies seem to be miniatures, as it were, and in a way copies [of Rome]” (Gell. NA 16.13.9), an assertion that later scholars took at face value, and which greatly influenced their studies of the topography of Roman colonies and colonisation (Salmon 1969; Brown 1980). It was said that a Roman colony could easily be recognised by its urban ‘kit’ that likened it to Rome, composed of a citadel with a Capitolium temple (a temple dedicated to the divine triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, as in Rome [Fig. 3]), a forum as the main political space, and, within it, a comitium (voting space) and a curia (the senate-house) (Bispham 2006; Quinn & Wilson 2013, 117, 126; Enríquez de Salamanca 2024, 120-125). This ‘kit’ would thus reaffirm Gellius’ notion and establish these colonies as enclaves of Romanisation. Can it be said that Urso presented this urban ‘kit’?

Fig. 3: Plan of the forum in Baelo Claudia, on the South coast of Spain The three temples on the North side of the forum (labelled A, B, and C at the top of the diagram) may have imitated the triple temple structure of the Capitolium. Image: Bonneville (2000) Fig. 4.

Given the scarcity of topographical surveys of the colony of Urso, we must turn to the lex Ursonensis once more and see what it tells us. It has been debated at length whether Urso had a Capitolium temple (Bendala Galán 1990, 12), and most debates focus on the mention of the Capitoline Triad on the charter itself, where it instructs the duumvirs and aediles to conduct shows and games for these deities (Urs. 70-71). This mention has been, for some, enough evidence to warrant the assertion of there being a Capitolium temple at Urso, but as Torelli clearly showed in a paper from 2014, the cult to the Capitoline Triad did not need a physical temple and could follow non-traditional forms (Torelli 2014). Given that we are focused on the topographical elements, and a Capitolium has not been unearthed at Urso, we cannot grant this point to the replica model.

The forum, and the comitium and curia present different problems. The forum and comitium are well attested in the charter, but there is no mention of a curia, nor has it been discovered. However, one might plausibly argue that there must have been a curia where the well-attested ordo decurionum could meet, and indeed that must have been the case. The forum and comitium, too, we have little reason to doubt. Surely this should be enough. However, as I have argued elsewhere – just like the existence of the forum at Corinth could easily be explained not in terms of replica, but of logical development of pre-Roman spaces (in this case, a Greek agora) – a forum, a comitium complex, and a curia in a pre-existing colonial city cannot easily be said to represent a copy of Rome, but could rather be the development of local institutions turned into the political heart of the new colonial city. One could further argue that the fact that the charter was written the same year the colony was founded, and these institutions are taken for granted, that some sort of similar places must have already existed that could be used to those effects (Enríquez de Salamanca 2024, 127-128, 130-131).

In short, the lex Ursonensis posits one of the most interesting pieces of evidence in the study of Roman intervention, Roman colonisation, provincial governance, Romanisation, and local reactions to Roman rule. In this post I hope to have showed how this charter might be used to reconstruct a picture of how Rome’s influence changed the cultural and political landscape of the provinces, in this case Baetica, but also that we should be careful about our pre-existing assumptions and how they influence how we read these sources.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Aulus Gellius. Attic Nights, Volume III: Books 14-20. Translated by J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927).

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Volume II: Books 3-7. Translated by H. Rackman (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942).

Secondary Sources:

Bendala Galán, M. (1990). “Capitolia Hispaniarum”, Anas 2/3, 11-36.

Bispham, E. 2006. “Coloniam Deducere: How Roman was Roman Colonization During the Middle Republic?”, in Greek and Roman Colonization, eds.: G. Bradley, J-P. Wilson (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales), 73-160.

Bonneville, J.-N. (2000) Belo VII. Le capitole (Madrid: Casa de Velázquez).

Brown, F.E. (1980). Cosa: the making of a Roman town (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press).

Curchin, L.A. (1990). The Local Magistrates of Roman Spain (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Enríquez de Salamanca, C. (2024). “The Emergence of the Replica Model? An Analysis of the Question of the ‘Copies of Rome’ in Late Republican Colonization Through Three Case-Studies”, Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica 30(1) 117-138.

Johnson, A.C., Coleman-Norton, P.R., Bourne, F.C., & Pharr, C. (1961). Ancient Roman Statutes: a translation with introduction, commentary, glossary, and index (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Luzón, J.M. & Castillo, E. (2007). “Evidencias arqueológicas de los signos de poder en Itálica”, in Culto Imperial: política y poder, eds.: T. Nogales & J. González. (Mérida: L'Erma di Bretschneider), 191-214.

Melchor Gil, E. (2011). “Élites Supralocales en la Bética: Entre la Civitas y la Provincia”, in Roma Generadora de Identidades. La Experiencia Hispana, eds.: A. Caballos Rufino & S. Lefebvre. (Madrid: Casa de Velázquez), 267-300.

Navarro Caballero, M. (2017) Perfectissima Femina: Femmes de l’élite dans l’Hispanie romaine (Bordeaux: Ausonius Éditions).

Quinn, J.C. & Wilson, A. (2013). “Capitolia”, Journal of Roman Studies 103, 117-173.

Rodríguez Neila, J.F. (1999). “Élites Municipales y Ejercicio del Poder en la Bética Romana”, in Élites y Promoción Social en la Hispania Romana, eds.: J.F. Rodríguez Neila & F.J. Navarro Santana (Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra S.A.), 25-102.

Salmon, E.T. (1969). Roman Colonization Under the Republic (London: Thames and Hudson).

Sánchez Moreno, C. (2013) “Lex coloniae Genetivae Iuliae seu Ursonensis”, in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, eds.: R.S. Bagnall, K. Brodersen, C.B. Champion, A. Erskine, S.R. Huebner. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell), 4037-4039.

Stylow, A. (1997). “Texto de la Lex Ursonensis”, Studia Histórica. Historia Antigua 15, 269-301.

Torelli, M. (2014). “Effigies parvae simulacraque Romae. La fortuna di un modello teorico repubblicano: Leptis Magna colonia romana”, in Roman Republican Colonization: New Perspectives from Archaeology and Ancient History, eds.: T. Stek, J. Pelgrom. (Rome: Palombi Editori), 335-356.

This post was written by Carlos Enríquez de Salamanca, a first year PhD candidate in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick funded by a Chancellor’s International Scholarship. Carlos’ PhD project focuses on the ways in which ancient identities were constructed and negotiated at the local and the imperial level in the province of Baetica (southern Spain). His other interests include Roman imperialism, political culture of the Republic and Empire, Roman colonization, and the daily life in the provinces.

Love and Loss: Commemorating Children in Romano-British Tombstones, by Zhian Zhang (March 2025)

[D(is)] M(anibus) Corellia Optata an(norum) XIII Secreti Manes qui regna Acherusia Ditis incolitis quos parva petunt post lumina vite exiguus cinis et simulacrum corpo(r)is umbra insontis gnate genitor spe captus iniqua supremum hunc nate miserandus defleo finem Q(uintus) Core(llius) Fortis pat(er) f(aciendum) c(uravit).

To the spirits of the departed: Corellia Optata, aged thirteen. You mysterious spirits who dwell in Pluto’s Acherusian realms, and whom the meagre ashes and the shade, empty semblance of the body, seek, following the brief light of life; father of an innocent daughter, I, a pitiable victim of unfair hope, bewail her final end. Quintus Corellius Fortis, her father, had this set up. (RIB 684, Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Tombstone of Corellia Optata (RIB 684), York, possibly 2nd century CE, now in the Yorkshire Museum (YORYM: 2007.6171). Image from York Museums Trust.

Tombstones are typically stone stelae inscribed with epitaphs and sometimes decorated with figural and/or non-figural reliefs. This funerary practice was introduced to Britain after the Roman conquest in 43 CE, which became an example of so-called “Romanisation”. Many have been found near Roman legionary forts such as those at Chester and Hadrian’s Wall, and most dedicatees are linked to the Roman military. These inscriptions and reliefs are more than just markers of identity—they provide us with valuable insights into social hierarchies, gender roles, and family relationships. They also serve as a commemorative language, revealing how people grieved and remembered their loved ones. Tombstones dedicated to children are particularly poignant, and they can shed light on childhood, early death, and how families coped with such loss.

Many tombstones bear only inscriptions and decorative patterns (such as Fig. 1), likely due to financial constraints or personal preference, and yet some include figural reliefs. However, these figures are often described as crudely carved with stumpy and disproportionate bodies that rarely resemble real individuals. This raises a question: what do these distinctive and publicly displayed tombstones invite viewers to reflect on or appreciate?

While searching all the figural reliefs, I was particularly struck by one which displayed a “floating” girl with a box-shaped body (Fig. 2). This tombstone, found in Corbridge, is dedicated to four-year-old Vellibia Ertola. She has a round face with a big rectangular nose. Her geometric form, dressed in a belted garment with stumpy limbs, gives her an abstract and non-naturalistic appearance. This portrait announces its presence as a young girl, but it seems also to distinguish her from a living body, while her floating position within the gabled niche evokes a spiritual and divine sense. Her frontal gaze invites viewers to engage with her, yet it creates a feeling of uneasiness. It is as if she is saying: I am here, yet I am not.

Fig. 2: Tombstone of Vellibia Ertola (RIB 1181), Corbridge, late 3rd or early 4th century CE, now in the Corbridge Museum (CO23338). Image reproduced by Salisbury (2022, 133) with the permission of the curator.

Πολλάκι τῷδ´ ὀλοϕυδνὰ κόρας ἐπὶ σάματι Κλείνα

μάτηρ ὠκύμορον παῖδ᾿ ἐβόασε ϕίλαν,

ψυχὰν ἀγκαλέουσα Φιλαινίδος, ἃ πρὸ γάμοιο

χλωρὸν ὑπὲρ ποταμοῦ χεῦμ᾿ Ἀχέροντος ἔβα.

Attributes like the one Ertola holds are a common feature on children’s tombstones, ranging from animals and fruit to scrolls or unidentified objects. On another tombstone from Old Penrith dedicated to a six-year-old boy, he holds a palm-branch in his right hand and a whip in his left (Fig. 3). This image, reminiscent of a chariot-race victory, may also represent his lost potential in adulthood. Like Vellibia Ertola, his bell-shaped body suggests that attributes, rather than individual likeness, were emphasised more to define a child’s identity. Comparing the girl’s apple with the boy’s whip, we can glimpse Roman gender ideals embedded in these memorials. Whatever these attributes might have meant to the family, to some extent they reflect the social and parental expectations placed on children. It is noteworthy that tombstones for girls and boys under the age of 17 are nearly equal in number (Adams & Tobler 2007, 21), which could be interpreted as evidence of emotional attachment to children, regardless of gender.

Fig. 3: Tombstone of Marcus Cocceius Nonnus (RIB 932), Old Penrith, after 96 CE, now in the British Museum (1969,0701.4). Image from the British Museum.

D(is) M(anibus)

Sudrenus

Ertole nomine

Vellibia felicissi

me vixit an(n)is IIII

diebus LX

To the spirits of the departed:

Sudrenus (set this up)

to Ertola, properly called

Vellibia, (who)

lived most happily four years

and sixty days.

Fig. 4: Tombstone of Vellibia Ertola (RIB 1181). Image from RIB online: https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1181

Fig. 5: Tombstone of Vacia (RIB 961), Carlisle, 2nd century CE, now in the Tullie House Museum (CALMG: 1998.384). Image from RIB online: https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/961Link opens in a new window.