The Iceni

Boudica's Tribe and homeland

Much like Cogidubnus in the south, Boudica's husband Prasutagus ruled as an independent ally of Rome, a client king. Prasutagus may have been one of the eleven kings who surrendered to the emperor Claudius following the Roman conquest in AD 43. On an inscription inscribed on arches on the Aqua Virgo in Rome, we read that the emperor received the surrender of eleven kings of the Britons defeated without any loss. Alternatively, he may have been installed as king following the defeat of a rebellion of the Iceni in AD 47 as recorded by Tacitus in his Annals (12.31):

"The Iceni, a powerful tribe, which war had not weakened, as they had voluntarily joined our alliance, were the first to resist. At their instigation the surrounding nations chose as a battlefield a spot walled in by a rude barrier, with a narrow approach, impenetrable to cavalry. Through these defences the Roman general, though he had with him only the allied troops, without the strength of the legions, attempted to break, and having assigned their positions to his cohorts, he equipped even his cavalry for the work of infantry. Then at a given signal they forced the barrier, routing the enemy who were entangled in their own defences. The rebels, conscious of their guilt, and finding escape barred, performed many noble feats."

The Iceni revolted along with the neighbouring Coritani and Catuvellauni (each of whom had made previous alliances with Rome), but were quickly suppressed by the Governor of the province, Publius Ostorius Scapula and a small force of auxiliaries. They had revolted against harsh measures taken against them, not against the Roman presence on the whole. The historian Miranda Aldhouse-Green cites this Iceni rebellion, in 47 CE, as the cause of Prasutagus' elevation to chief of the tribe. This rebellion was unsuccessful and it is unclear what role Prasutagus played in it but it seems clear that the Romans saw Prasutagus as a leader who could keep the peace between the Iceni and Rome.

At his death sometime before AD 60, Prasutagus left his kingdom jointly to his two daughters by Boudica, and to the Roman emperor in his will. Aldhouse-Green also notes the significance of Prasutagus' will, which divided his estate between his daughters and Rome and omitted Boudica, as evidence of the queen's hostility toward Rome even before the actions of Rome described by Tacitus and Cassius Dio (see below). She argues that, by leaving her out of the will, Prasutagus hoped his daughters would continue his policy of cooperation. After his death, however, all hope of the Iceni existing peacefully with Rome was lost as the will was ignored. Instead, the kingdom was annexed and his property taken. According to Tacitus (Annals 14.31), Boudica was flogged and her daughters raped. Cassius Dio (Roman History 62.2) gives a different account, saying that previous imperial donations to influential Britons were confiscated and the Roman financier and philosopher Seneca called in the loans he had forced on the reluctant Britons. See the section on Ancient Sources.

Whatever the exact truth, the idea that the extraordinary Romans actions were undertaken as a reaction to a prior distrust of Boudica is an intriguing one, and changes the story of the revolt from a simple act of revenge for an unspeakable act or acts.

The Character of the Iceni

The information here is adapted from Boudica: Warrior Woman of Roman Britain by Caitlin C. Gillespie (Oxford University Press 2018).

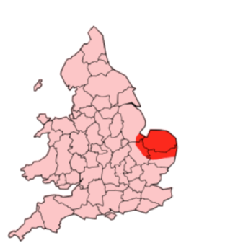

The Iceni were a British tribal group who lived in East Anglia, occupying areas of Norfolk, northeast Cambridgeshire, and the northern parts of Suffolk. They may be the same as Caesar’s Cenimagni, interpreted as the Iceni Magni, or “great Iceni,” one of five “tribes” that submitted to Caesar after the Trinovantes came under his protection.

The Iceni appear to have been a wealthy people interested in metalware and horses - archaeological finds of horse-related objects are common, while weapons and imported pottery are rare. Icenian coins often show horses (see below) while others featuring women and horses have been used to suggest the presence of female warriors among the Iceni.

First century BC Iceni coin

After the Emperor Claudius’s conquest in AD 34 the Iceni became Roman allies. They were allowed to retain their land, have their own ruler, and mint their own silver coins, rather than use the coinage of their conquerors. Despite this alliance, the Iceni and their neighbours revolted in the winter of AD 47/48 after Aulus Plautius had left for Rome and his replacement, Publius Ostorius Scapula, had not yet arrived.

Scapula was responsible for appropriating the land around Camulodunum (Colchester) from the Trinovantes and distributing it to Roman military veterans. Camulodunum, named for the Celtic war god Camulos, was renamed the Colonia Claudia Victricensis (the colony of Claudius the Victorious). Scapula also forbade all Britons, including allies of Rome, from carrying arms aside from hunting weapons. It was to be this veterans' town that Boudica was to first attack in her revolt of AD 60-61.

When Prasutagus became a client king of Rome, this is the first indication of the political organization of the Iceni, and it is possible they may not have had a prior king - they may have been ruled by a confederation of communities or another form of social organization. We have no clear verification of Boudica or Prasutagus, even from the coins of the first century, and we are forced to rely on the Roman written record of Tacitus and Cassius Dio for their existence and for their names. Furthermore, we are unsure where the Iceni centre of power was located and where Prasutagus and his family lived.