Diversity in the Roman Army

Introduction

Perhaps the greatest influence on the diversity of the Romans, both in Britain and across the entire Roman empire, was the diversity of the Roman army whose legions, recruited from Roman citizens, were posted all over the empire. We must remember that these Roman citizens were not just those citizens from the city of Rome itself, or Italy, but of the entire empire. Local citizens could be recruited into the army, and in fact supplying men for the legions was a central part of the process of becoming part of the empire.

During their service, soldiers often took common-law wives and married them on retirement, creating new generations of Roman citizens outside Italy who would then be eligible for legionary service.

If you think of the XX Legion, who we know were involved near Coventry putting down the revolt of Boudica, their ranks may well have been made up of men born in the areas they had previously been posted, so from all across Europe and possibly beyond. So when we consider the Roman legionaries who once were stationed at the Lunt Roman Fort, we must imagine a body of men from across the Roman Empire, each perhaps holding onto identities or adapting to circumstances in very individual ways.

Multiple Identities and Diversity of Ethnicities in the Army

The following section has been taken from the Roman Leicester resources: and is based on the scholarship of Mattingly (2007).

Until the second quarter of the second century when British recruits became more common, legionaries came initially mainly from Italy (81%), but by the end of the first century were mainly from North Africa and the western provinces of Hispana, Gallia, Germania, Raetia (an Alpine province) and Noricum (roughly modern Austria/Slovenia). By this time Italian recruits constituted only about 20% of the number. Thus the army was ethnically highly diverse. Auxiliary troops introduced an even greater ethnic diversity, with men from Batavia (part of the modern Netherlands), Tungria (part of modern Belgium) and Thrace (roughly modern Bulgaria).

Although at the beginning of the occupation there were mass conscriptions in Batavia, Tungria and Thrace to raise units of auxiliaries, over time these units were supplemented not only by British recruits, but also by recruits from elsewhere in the empire. Mattingly cites examples of three men who served in a Tungrian unit but whose origins were in Germania Inferior (the west bank of the Rhine) and the Alpine province of Raetia. It appears however, that a unit’s fighting history and traditions were important factors in creating a ‘unit identity’ irrespective of the soldiers’ ethnic origins. He also notes that where there were large numbers of men broadly of one ethnicity in a unit or garrison, variants of the military identity formed by common training, living routines and religious practices might emerge. Thus, amongst a large group of third century Germanic recruits at Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall, Germanic deities were celebrated in addition to those in the official army calendar of religious practice, and Frisian pottery was also found there.

On retirement, legionaries received cash or some land. They would have the option of living in a colonia, a town founded for veterans with land allotments surrounding it. A legionary retiring from one of the legions serving in Britain could settle in one of the three British coloniae, at Colchester, Gloucester and Lincoln, or one elsewhere in the empire. Alternatively he could take money instead of land and return to his birthplace, or use the money to buy a rural estate. If he already had a family, he might choose to settle in the garrison settlement adjacent to where he had been based and set up a trade or business. In some cases, the legionary might obtain administrative employment in London working for the governor’s administration. The sons of veterans were quite likely to become voluntary recruits, especially those who grew up in the settlement next to their father’s former garrison.

How diverse was Roman Britain? Septimius Severus and the Ethiopian

The following is adapted from a 2017 blog by By Dr Matthew Nicholls of the Department of Classics, University of Reading which discusses the diversity of Roman Britain

The legions of the Roman army, recruited from Roman citizens, were posted all over the empire. Soldiers might take local common-law wives and marry them on retirement, creating new generations of Roman citizens outside Italy who would then be eligible for legionary service.

The internet discussion [see section on Diversity in Roman Britain] was particularly prompted by the appearance of a black Roman soldier in the detachment building Hadrian’s Wall, but in fact there is an ancient account of precisely this – the emperor Septimius Severus (himself in fact an African, from Libya) was inspecting his troops on the Wall when one of the garrison’s well-known jokers, an ‘Ethiopian’, offered him a garland.

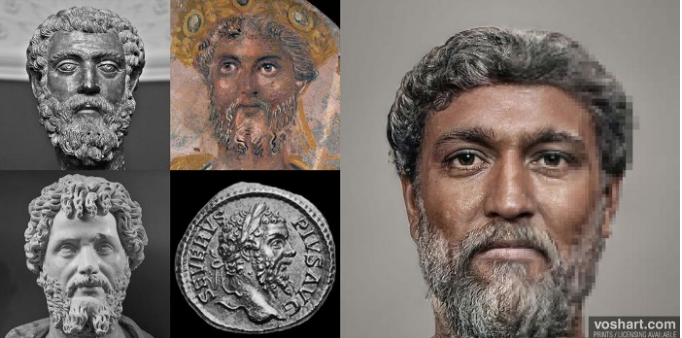

Virtual reality specialist Daniel Voshart has recently reconstructed realistic depictions of Roman rulers (see above). Voshart's depiction of Septimius Severus — who hailed from present-day Libya — shows an emperor of darker complexion, with famously thick curls and a beard. Such reconstructions are always controversial, but these of Voshart certainly bring these characters to life.

The following is the account given in the Historia Augusta on the meeting of Severus and the Ethiopian at Hadrian's Wall:

22.1. The death of Severus was foreshadowed by the following events: he himself dreamed that he was snatched up to the heavens in a jewelled car drawn by four eagles, whilst some vast shape, I know not what, but resembling a man, flew on before. And while he was being snatched up, he counted out the numbers eighty and nine, and beyond this number of years he did not live so much as one, for he was an old man when he came to the throne...

4. On another occasion, when he was returning to his nearest quarters from an inspection of the wall at Luguvallum in Britain, at a time when he had not only proved victorious but had concluded a perpetual peace, just as he was wondering what omen would present itself, an Ethiopian soldier, who was famous among buffoons and always a notable jester, met him with a garland of cypress-boughs.

5. And when Severus in a rage ordered that the man be removed from his sight, troubled as he was by the man's ominous colour and the ominous nature of the garland, the Ethiopian by way of jest cried, it is said, "You have been all things, you have conquered all things, now, O conqueror, be a god."

6. And when on reaching the town he wished to perform a sacrifice, in the first place, through a misunderstanding on the part of the rustic soothsayer, he was taken to the Temple of Bellona, and, in the second place, the victims provided him were black.

7. And then, when he abandoned the sacrifice in disgust and betook himself to the Palace, through some carelessness on the part of the attendants the black victims followed him up to its very doors.

Severus was startled by the apparent omen, associating the soldier’s black colour as a portent of his own imminent death, but no-one seems to have been particularly surprised at the presence of an ‘Ethiopian’ (that is, a black African) at the northern edge of the Roman empire. There were other Africans on the wall – a third-century AD cohort of Mauri from north west Africa are also attested in an inscription at Burgh-by-Sands near Carlisle.

Auxiliary military units, levied from non-citizens, were deliberately posted to areas of the empire far from their troops’ home province, so Hadrian’s Wall also had garrisons of Tungrian and Batavian troops from Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as units from as far away as Syria [See below].

Auxiliary units like these passed on Roman military discipline, Latin, and Roman cultural habits and often rewarded their soldiers with grants of citizenship on retirement, producing more new citizens with a long training in Roman ways. And Roman army units in frontier provinces built roads and harbours and created instant large markets for food, drink, and services, stimulating the growth of towns outside the fortress gates. In the long-term, this also monetised trading economies that drew in more civilian settlers from around the empire.

We know about some of these settlers from archaeological evidence and inscriptions. Researchers the University of Reading have worked on both. Dr Hella Eckardt’s analysis of skeletal remains found in York suggest that the city was home to immigrants from North Africa (such as the so-called Ivory Bangle Lady), while Professor Peter Kruschwitz has written on moving inscriptions that document the lives and deaths of immigrants in the Roman empire [see section on Diversity for more on Syrians in Roman Britain]. For example, a remarkable monument, discovered in Arbeia (South Shields) at the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall, documents the life of a British wife of a Syrian immigrant from Palmyra, including text in Palmyrene, one of several pieces of evidence for a near eastern people in northern Britain.

Diversity at Lunt Roman Fort

We do not know for certain which legion or legions or sections thereof were stationed at Lunt Fort during its occupation. A number of legions came to the area to put down the revolt of Boudica in AD 60-61, and it is possible that cohorts from some of these were to be found at various times at the Lunt.

The discovery of a silver ring at the site which seems to depict the XX of the Valeria Victrix suggests that members of the XX Legion were present at the site at some point, and most likely around AD 61. One thing to bear in mind is that in each place the Legion was stationed during its long history, it would have recruited locals in to its ranks, so that by the time it arrived in the W Midlands, the Legion would have contained members from the Balkans, Italy, Germany, Spain, and no doubt some from N Africa as well.

Equally, centurions did not necessarily remain attached to one legion or serve in one province for their whole careers. Mattingly cites one centurion T. Flavius Virilis known to have served in three different British legions including the XX Valeria Victrix then one in Africa and one in Italy in a career spanning forty-five years (2007, 185). His British wife Lollia Bodicca (!) buried him in Numidia (modern Algeria) aged 70. He may even have been British himself.