The Evidence for Diversity in Roman Britain

Introduction

A few years ago, in 2016, a BBC created animation on Roman Britain caused some controversy through its depiction of a typical Romano-British family as shown below.

The depiction of a racially mixed family group had some commentators up in arms screaming that the political correctness brigade had once again stepped in to give us an image far from what might have been typical. And yet evidence suggests that the scene above was a perfectly plausible one for Roman Britain and in fact allows us to open up a very interesting discussion about the diverse make up of the Romans who found themselves on these shores. Who were they are where did they come from? And what evidence do we have?

In the following sections we will present a number of discussions, some arising from the BBC controversy, and will present the evidence for the diverse nature of the Romans who lived in Britain during the first few centuries after the Roman invasion.

How diverse was Roman Britain?

On July 28, 2017 a blog by Dr Matthew Nicholls of the Department of Classics, University of Reading discussed the diversity of Roman Britain and is quoted here in full as it gives an excellent overview of the whole topic:

"A heated conversation arose on social media on Wednesday surrounding the question of the racial diversity of Roman Britain, or the Roman empire more generally.

The tweet from Alt Right commentator Paul Joseph Watson, that kicked off the debate.

There is plenty of evidence that the Roman empire was relatively diverse, as might be expected from an empire that encouraged trade and mobility across a territory that extended from Hadrian’s Wall to north Africa, the Rhine, and the Euphrates (and which, less positively, enslaved and moved conquered populations around by force). Rome itself was a melting pot of people from all over the Mediterranean and beyond (satirical poets moan about it, and we have the evidence of tombstones). Outside Italy the Roman army in particular acted as medium for change and movement in several ways.

Its legions, recruited from Roman citizens, were posted all over the empire. Soldiers might take local common-law wives and marry them on retirement, creating new generations of Roman citizens outside Italy who would then be eligible for legionary service.

The internet discussion was particularly prompted by the appearance of a black Roman soldier in the detachment building Hadrian’s Wall, but in fact there is an ancient account of precisely this – the emperor Septimius Severus (himself in fact an African, from Libya) was inspecting his troops on the Wall when one of the garrison’s well-known jokers, an ‘Ethiopian’, offered him a garland.

Severus was startled by the apparent omen, associating the soldier’s black colour as a portent of his own imminent death, but no-one seems to have been particularly surprised at the presence of an ‘Ethiopian’ (that is, a black African) at the northern edge of the Roman empire (Hist. Aug. Severus 22). There were other Africans on the wall – a third-century AD cohort of Mauri from north west Africa are also attested in an inscription at Burgh-by-Sands near Carlisle.

“Hadrian’s Wall had garrisons of Tungrian and Batavian troops from Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as units from as far away as Syria”

Auxiliary military units, levied from non-citizens, were deliberately posted to areas of the empire far from their troops’ home province, so Hadrian’s Wall also had garrisons of Tungrian and Batavian troops from Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as units from as far away as Syria.

Auxiliary units like these passed on Roman military discipline, Latin, and Roman cultural habits and often rewarded their soldiers with grants of citizenship on retirement, producing more new citizens with a long training in Roman ways. And Roman army units in frontier provinces built roads and harbours and created instant large markets for food, drink, and services, stimulating the growth of towns outside the fortress gates. In the long-term, this also monetised trading economies that drew in more civilian settlers from around the empire.

We know about some of these settlers from archaeological evidence and inscriptions. Colleagues at the University of Reading have worked on both. Dr Hella Eckardt’s analysis of skeletal remains found in York suggest that the city was home to immigrants from North Africa (find out more here), while Professor Peter Kruschwitz has written on moving inscriptions that document the lives and deaths of immigrants in the Roman empire (see below).

[A] remarkable monument, discovered in Arbeia (South Shields) at the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall, documents the life of a British wife of a Syrian immigrant from Palmyra, including text in Palmyrene, one of several pieces of evidence for a near eastern people in northern Britain [see below]."

Quintus Lollius Urbicus?

According to Prof Mary Beard in a Guardian article, a man called Quintus Lollius Urbicus, a Berber from what is now Algeria who became governor of Roman Britain from AD 139-142, may have been the inspiration for the BBC video that triggered the storm.

Explaining that it can be difficult to be sure of ethnicity because Africans took on Roman names, she said: “Even in the case of Septimius Severus, the first Roman emperor from Africa [Libya], we don’t actually know the colour of his skin, how far he was ‘native’, how far the descendent of Italian settler. The same goes for Quintus Lollius Urbicus, often claimed to be Berber, which he may well have been, but it isn’t certain.”

Beyond the colour of his skin remains the question of identity and how Quintus Lollius Urbicus viewed or thought himself. Descendent of an Italian settler? North African Berber? Citizen of the Roman Empire? All are possibilities.

Scientific Evidence for Black Romans in Britain?

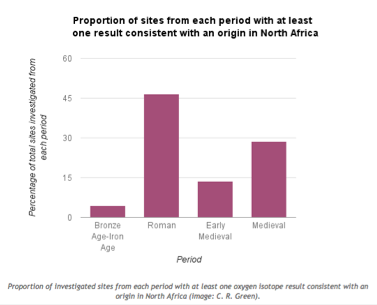

So what can we say about the depiction of the black Roman soldier in the BBC video? Well, scientific evidence exists for the presence of North Africans in over 45% of the sites investigated as part of a study published in 2012 which identified origins using analysis of tooth enamel.

The investigation was summed up in A note on the evidence for African migrants in Britain from the Bronze Age to the medieval period from the blog of Dr Caitlin Green of the ICE Cambridge University on Monday, 23 May 2016. The diagram from the blog as shown below revealed the findings clearly for the Roman period.

The analysis was based on the fact that oxygen isotopes (different 'types' of oxygen molecules which differ slightly in atomic weight) found in your tooth enamel - and taken in via drinking water - will differ according to where you were brought up. Isotopes at a level consistent with an origin in North Africa were very prevalent during the Roman era—the mid-first to early fifth centuries AD—with evidence being found at Winchester (Lankhills), Gloucester, York (three sites: Trentholme Drive, The Railway & Driffield Terrace), Scorton near Catterick, and Wasperton. Furthermore, nearly 47% of all Roman sites where the analysis was undertaken have produced evidence suggestive of the presence of people who grew up in North Africa, a significantly higher proportion than is found for any other era.

Syrians in Roman Britain

On September 6, 2015 Peter Kruschwitz, Professor of Ancient Cultural History of the University of Vienna posted an article on his blog titled What have the Syrians ever done for us...?

The blog was in part inspired by the negative press on the Syrians at the time of its writing given the actions of ISIS in Syria at sites such as Palmyra, and the heart breaking images of the body of the three year old Syrian refugee boy Aylan Kurdi, washed up on the beach in Turkey. With certain sections of the British tabloid press forced to re-evaluate their thoughts on immigration given the image of Aylan Kurdi, Prof Kruschwitz sought to investigate the earlier immigration of Syrians into Britain during the Roman period, highlighting the colour and diversity they brought to these shores:

The historical presence of Syrians in Britain is one such story, however – and it dates back a lot further than one might at first expect. In fact, it dates back – at least! – to Roman times, when Syrians, as part of the Roman auxiliary forces, helped to establish and to build the province of Britannia.

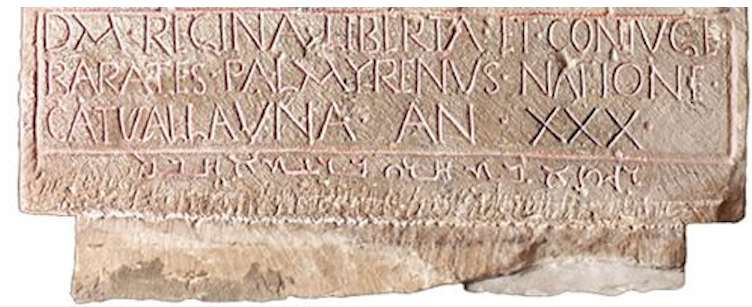

In the corpus of Roman inscriptions from Britain, there are numerous examples of individuals who self-identify as Syrians by nationality. The single most remarkable instance is attested on a lavish (and undoubtedly expensive) memorial that was discovered at Arbeia (South Shields), by the Eastern end of Hadrian’s wall:

The piece – a tombstone for a woman called Regina of uncertain date (possibly second century A. D.?) – consists of three essential components, only two of which may immediately appear to the untrained eye: a sculpture, and two inscriptions (yes, two, not just one).

The ‘main’ (as in: ‘bigger, framed’) inscription is written in Latin and reads as follows:

D(is) M(anibus). Regina(m) liberta(m) et coniuge(m)

Barat(h)es Palmyrenus natione

Catvallauna(m) an(norum) XXX.

In English:

To the Spirits of the Departed. Barathes of Palmyra (sc. buries here) Regina, a freedwoman and his wife, a Catuvellaunian by origin, aged 30.

Barathes, a Syrian, who self-identifies in this inscription as a native of Palmyra, would appear to be a foreigner (peregrinus) not only to Britain, but to the Roman Empire – and one may well wonder what he and his wife Regina were doing in Roman Britain near Hadrian’s wall.

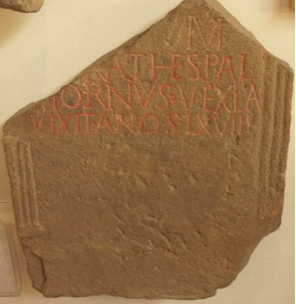

Another inscription from Hadrian’s wall, discovered at the Roman fort of Coria(Corbridge) just over 25 miles away from the above item and substantially less well executed, mentions another citizen of Palmyra. Due to its fragmentation, the stone does not exhibit his name in full – all that survives is the second half of it: [- – -]rathes (RIB 1171):

It is tempting (and perfectly plausible) to supplement this as [Ba]rathes. But is this the same man as the Barathes of the inscription above? After all, Barathes is not an altogether uncommon name in Palmyrene nomenclature. But how many of them will have been at Hadrian’s wall at the time…?

If – and that is a big if – the two Baratheses are identical (to be clear: more likely than not, they were NOT identical!), then the second stone reveals the man’s occupation: according to the Corbridge stone he was a vexil(l)a(rius) and died aged 68 (vixit an(n)os LXVIII).

The most obvious understanding of vexil(l)a(rius) is ‘standard-bearer’ or ‘flag-bearer’, i. e. a military position. As suggested before, however, there are very good reasons to assume that neither Barathes (whether or not they were identical) were a Roman citizens, but peregrini instead. In that case, one must wonder if the Barathes of RIB 1171 was a military man at all, or whether vexillarius was a title for either a merchant in flags and other signs (unattested otherwise, but not to be ruled out a priori) or whether he held a ceremonial function in a collegium fabrorum (‘guild of engineers’), for example.

The discrepancy in lavishness between the stone for the wife and for Barathes himself (if identical!) could thus be explained by a decrease in wealth, once Barathes had reached a certain age and could no longer work as a craftsman.

Be that as it may (and once again, the identification of the two, as proposed by some, is tenuous at best). Returning to the stone from South Shields, one must wonder about another detail: Regina, the wife, is described as a native of the Britannic tribe of the Catuvellauni as well as a freedwoman. The Catuvellauni were a Celtic tribe that inhabited an area north of modern-day London, roughly covering modern-day Hertfordshire and stretching as far north as Cambridgeshire.

How did she end up (i) at Hadrian’s wall and (ii) in Barathes’ possession, so that he could act as her patron (though not under Roman but, presumably, under Palmyrene law)?

The first question is impossible to answer. The second question cannot be answered with any certainty, but there are two main options: either she was captured and sold into slavery as a result of a Roman military campaign, or – equally possible – she was sold into slavery by her own family.

It is not clear as to whether Barathes was the ‘first’ owner of Regina as a slave, or whether he acquired her from someone else. As Regina (‘queen’) is a Latin name unlikely to be her native Celtic name (and hardly a Palmyrene name, unlike Barathes’), one must assume that she took this name during her enslavement.

The way in which Barathes chose to have his former slave and then wife represented in the sculpture of her tombstone lives up to the notion of, if not a queen, an eminently dignified, upper-class lady. The editors of the Roman Inscriptions of Britain describe the artwork of the stone as follows:

‘[T]he deceased sits facing front in a wicker chair. She wears a long-sleeved robe over her tunic, which reaches to her feet. Round her neck is a necklace of cable pattern, and on her wrists similar bracelets. On her lap she holds a distaff and spindle, while at her left side is her work-basket with balls of wool. With her right hand she holds open her unlocked jewellery-box. Her head is surrounded by a large nimbus (…)’.

Regina may not have been a queen in real life, but Barathes certainly presents her as almost sitting on a throne – presented in the garments and posture of a lady from Palmyra, dignified, wealthy, leading a distinguished, civilised life up to the time of her (relatively young) demise.

There is another aspect to the memorial, however, that is quite indicative of both Barathes’ attitude towards identity and his relationship with Regina. As mentioned initially, the monument does not only exhibit one (Latin) inscription, but two. Underneath the framed Latin inscription, there is a second one, written in Barathes’ native tongue, Palmyrene, which reads as follows:

רגיןאבתחריברעתאחבל

Regina, freedwoman of Barathes: alas!

The Latin inscription pays heed to circumstance – an environment in which Latin had become the language of the rulers and in which the couple had learnt to survive (and apparently to do reasonably well – at least to a certain point in Barathes’ life). It operates with official terms such as liberta (‘freedwoman) and coniux (‘wife’) – though they are unlikely to be labels under Roman law (as mentioned before).

In letters rather less awkwardly written than the Latin (leading some scholars to believe that this was carved by an Eastern craftsman rather than a local one), the inscription does not merely repeat the essential information in the widower’s own language – it adds the personal expression of grief, ‘alas!’ to it, visible only to those who pay attention to the ‘fine print’ at the bottom, understandable only to those who know the script and the language, meaningful only to Barathes himself. It is the personal aside of someone who has largely accepted the leading culture for himself, without being prepared to bid farewell to his own identity – that of a foreigner, thousands of miles away from his native Palmyra in Syria.

Barathes, the Syrian in Roman Britain, has done something beautiful. He acquired, freed, and married a girl from Britain, whose life had taken a disastrous turn – becoming a slave, either as a result of Roman campaigns or as a result of her family’s poverty (or greed) in uncertain times. He, as the tombstone suggests, gave her dignity, safety, and made her his queen, not only in name.

Times have changed a lot. Regina’s story is one that, nowadays, happens on a daily basis in Syria, in Palmyra, in the war-torn Near East, under the vicious regime of ISIS fighters and other parties.

Who will save those people from their predicament and restore their well-being and dignity?

Who will be their Barathes?

Other British Romans from across the Empire

Linked to the University of Reading, some great resources on diversity have been created by Runnymede, the UK's leading independent race equality think tank. Their Romans Revealed site gives information on various individuals with possible links to the continent.

For example, check out the information on an individual they call Piscarius who they think was born in a colder climate, possibly off the coast of Poland - his story is useful for discussions and activities about movement and settlement. Another individual, Savariana is also a helpful character to use for discussions about second or third generation migration as some of her grave goods, her bracelets for example, suggest that members of her family may have been ‘incomers’. Finally, Julia's grave goods suggest that she may have had North African heritage and have been quite wealthy. Her example can be used to talk about how diverse, both the Roman Empire generally and Roman Britain in particular, was, but also, in view of her possible wealth, to challenge views about what African Romans may have been like.

Mobility, Migration, and Diasporas in Roman Britain

Hella Eckardt and Gundula Müldner - Adapted from The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain (2014)

Inscriptions can identify foreigners through individual names, stated places of origin, and reference to regionally specific cults or calendars. From this sort of data we can build up personal, individual histories and allow for the exploration of wider patterns in terms of age, gender, and status. However, the evidence is unevenly distributed (we rely on inscriptions surviving and being legible) and there are relatively few inscriptions known from Britain in comparison with other provinces. The evidence is also biased towards urban and military areas, as opposed to small settlements or farms for example.

Across the empire, out of almost 600 inscriptions studied, 623 examples have been found of travellers or foreigners - an intricate web of travel in all directions: Spaniards in Italy, Pannonians (an area in central Europe around modern day Hungary) in Dalmatia (Croatia), Gauls (modern day France, Germany and other areas of central and western Europe) in Africa (see Handley 2011: 17).

The reasons for travel are diverse, including war/soldiery, pilgrimage, ecclesiastical business, exile, trade, and the emigration of individuals and families; there is also some evidence that the dead were moved, sometimes over considerable time periods and distances (Handley 2011:53–62).

Ultimately, it is in any case not the identification of biological origin that is truly of interest, but its interplay with social identity. As today, people make choices about whether to cling to an old, national, or ethnic identity or to adopt a new one—a decision that may be described as the ‘sport team choice’ (Handley 2011: preface).

Digging up migration history: The Ivory Bangle Lady

The Our Migratory History website presents the often untold stories of the generations of migrants who came to and shaped the British Isles. While it is primarily designed to support teachers and students studying migration to Britain, its aim is to be a useful resource for anyone interested in Britain’s migration history.

One way we can learn about early migration history is through the work of archaeologists, who have studied human remains to learn more about the people of Roman Britain. For example, the grave of a young woman (see main source above) was discovered in 1901 in Sycamore Terrace York; she was buried in a stone sarcophagus with very rich grave goods (objects placed into a burial for the afterlife, or as an offering to the dead) in the later 4th century. The objects placed into her grave included bracelets made from local jet and more exotic ones made of ivory. A short inscription on a bone mount, that once probably decorated a box, suggests that this high status young woman was a Christian as it says ‘Hail, sister, may you live in God’. Recently, the skull and teeth of her skeleton, which have been stored in Yorkshire Museum, were examined by scientists at the University of Reading.

The shape of her skull suggests that she had North African ancestry; this is not very surprising in a place like York, where inscriptions and written sources mention Africans. People from Africa who came to Britain include the Emperor Septimius Severus, who was born in what is Now Libya and ruled from AD 193-211.

Archaeological scientists can also analyse the chemical signatures preserved in human teeth. The ratios of stable isotopes such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and strontium in human teeth can provide information about ancient diet and origin. Oxygen and strontium signatures vary depending on the climate and underlying geology of the area where an individual grew up. Individuals from hot, coastal, areas will have a different signature to those who grew up in cooler areas of continental Europe. However, it is important to stress that isotope analysis is better at excluding local origin (i.e. an individual’s signature is very different from the local signatures) than pinpointing a specific area of origin (i.e. many areas have similar isotope signatures).

Studies of the remains of the Ivory Bangle Lady suggest that she was born and brought up in the south of Britain, or the continent, rather than in Africa. Archaeologists can interpret this finding in a number of ways. For example, it is possible that one parent of the Ivory Bangle Lady was from North Africa, but that she grew up in a different part of the Empire. Other skeletons from York and other Romano-British towns show that some incomers (as identified by their isotopic signatures) look almost like locals in terms of their burial rites and grave goods, while some archaeologically very exotic burials are in fact those of people born locally. Why could this be? We need to consider the fact that the dead do not bury themselves. Grave goods and burial rites might be shaped by parents or partners who had a different geographical origin to the deceased. A few hundred skeletons from the Roman period have now been studied by scientists using what is a very expensive technique, and the results show high levels of mobility and migration – up to 30% in some towns. However, the sample study is biased as it examines mostly unusual and exotic burials, so actual migration levels were likely much lower. A different picture of movement would probably emerge if countryside burials for the same period were sampled.

Cambridge Faculty statement concerning ethnic diversity in Roman Britain

"Roman Britain has long been an important part of the teaching and research in the Faculty of Classics. The question of ethnic diversity in the province has been getting unusual amounts of attention recently. Professor Mary Beard has been at the centre of some of this attention. In the Faculty we welcome and encourage public interest in, and reasoned debate about, the ancient world, such as Professor Beard has always sought to encourage. The evidence is in fact overwhelming that Roman Britain was indeed a multi-ethnic society. This was not, of course, evenly spread through the province, and it would have been infinitely more noticeable — it can be assumed — in an urban or military context than in a rural one. There are, however, still significant gaps in our understanding. New scientific evidence (including but not limited to genetic data) offers exciting ways forward, but it needs to be interpreted carefully."

Bibliography

BBC Story of Britain https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01zfw4w

How diverse was Roman Britain? By Dr Matthew Nicholls, Department of Classics, University of Reading https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/the-forum/2017/07/28/how-diverse-was-roman-britain/#comments

‘Mary Beard abused on Twitter over Roman Britain's ethnic diversity’ – Guardian 6th August 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/aug/06/mary-beard-twitter-abuse-roman-britain-ethnic-diversity

A note on the evidence for African migrants in Britain from the Bronze Age to the medieval period – Dr Caitlin Green https://www.caitlingreen.org/2016/05/a-note-on-evidence-for-african-migrants.html?m=1

What have the Syrians ever done for us? Peter Kruschwitz https://thepetrifiedmuse.blog/2015/09/06/what-have-the-syrians-ever-done-for-us/

Clash of Cultures?: The Romano-British Period in the West Midlands Roger White and Mike Hodder 2018. Oxbow Books.

An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire 54BC-AD409. David J. Mattingly, 2007. Penguin History of Britain.

‘Mobility, Migration, and Diasporas in Roman Britain’ by Hella Eckardt and Gundula Müldner in The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain Edited by Martin Millett, Louise Revell, and Alison Moore, 2016. Oxford University Press.

Dying on Foreign Shores: Travel and Mobility in the Late-Antique West. Mark Handley 2011 Journal of Roman Archaeology Suppl. 86