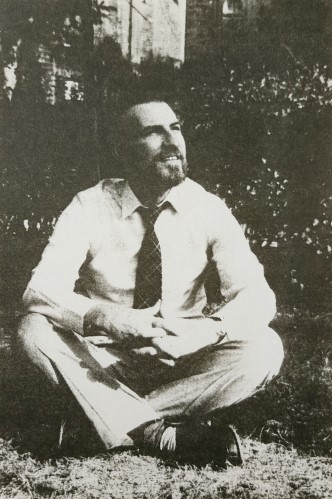

Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres

5th December 1942 - 23rd July 2019 "Our Friend"

Salvador was one of the most optimistic people I have ever met. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he assured me and all his other friends that he was not at all afraid and that he would simply deal with it as best he could. The last time we spoke he was upbeat and talked to me about his writing; the friend who spoke to him two days before he died reported a similar conversation. He approached death as he did life: with openness and curiosity and the belief that something better was just around the corner. As he wrote in one of his poems, Caminar (Walking):

We are all seeking a place,

following a star, a destiny.

So just keep on walking

walking down that narrow road

Salvador was a brilliant teacher. He undertook to get students through GCSE Spanish after just 2 weeks of his intensive course, and at one stage in the early years of Warwick practically everyone I knew had signed up to study Spanish with Salvador: students, academics and their families, administrators and at least 2 vice-chancellors’ wives. His technique was highly individual: he wanted the language classroom to be exciting, and so did everything he could to ensure that his students stayed alert. I remember his telling me that the smoking ban meant that he could no longer throw cigarettes around the room, so he threw bonbons instead. And like a squirrel he collected anything and everything that might help people learn more Spanish: he was chased out of a church once by an irate elderly lady for taking down some posters he thought could be useful, and he persuaded the cabin crew on at least one Iberia flight to give him a pile of Spanish sick bags for the classroom.

As he explained, short intensive courses can work, but only in the short term, so what counts in learning another language is to have repeated experiences of what we might call the shock of recognition. By unsettling students and cutting through their preconception that studying a language might be boring a teacher can have genuine, lasting impact.

But Salvador’s method, successful though it was, depended also on his personality, on the energy he generated in the classroom. For a while he took part in my option course on Latin American poetry, where he would sweep in to the seminar room and read poems aloud, because as he said, hearing the poetry would help as much, if not more, than critical analysis. There was a strong performance side to Salvador, and his readings were always a tour de force.

As messages have come in over the last few days since I heard that he had died, certain adjectives keep recurring: gentle, generous, kind, open-hearted, and also, fun. For Salvador was fun, he brightened a room when he came into it, which explains why he was so successful as a teacher and also why, today, so many of the vast number of friends he made all over the world feel that we have lost someone whose time on this earth really made a difference. Rest in peace, back in your beloved Spanish village, Salva, vaya con Dios, amigo nuestro muy amado.

Susan Bassnett July 26th 2019

Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres retired from the University of Warwick in 2008, after 34 years service. To recognise his outstanding achievements and contribution to the University, he was awarded a Warwick Award for Teaching Excellence in a new, special category of “Lifetime Achievement”, which was the first of its kind to be awarded by the University.

Salvador made an enormous contribution to the educational life of the University over many years.

He was a pioneering teacher of the Spanish language with a method of teaching which was innovative and highly reflective. He had an enormous impact, not only in Warwick, but in the wider world with his teaching, his textbooks and his work with the media. He never took a sabbatical, or cancelled a single lesson. A clear favourite among generations of students, he once said “If I’m not clear in my mind what I’m teaching, I will create confusion. Learning is based on trust, and the students must trust that I can teach them well.” Students truly appreciated his commitment and enthusiasm, and his ability to touch reach out to all kinds of people.

During his working life at the University, Salvador also produced language courses for the BBC – España Viva and Paso Doble (as academic advisor) – and worked with The Times Educational Supplement and Royal Shakespeare Company. He also brought his unique style of teaching around the world, and gained an international reputation as a language teacher. His invitations to teach on short courses across the globe from Iceland, Sweden and Poland to India, Malaysia and the Philippines were testimony to his international standing.

Salvador brought his considerable knowledge of Hispanic literature and history to bear on his language teaching, from beginner to post-graduate. He wove elements of literature, (and poetry and song in particular), into his lessons from the outset, and did not treat literary works as though they belonged purely in the academic sphere. He was also a translator of seminally important Hispanic works of literature and poetry, and a committed humanitarian. Some of his work can be seen here:

He worked on translations of, among others, Miguel de Unamuno, Jorge Luis Borges, Antonio Machado, Federico García Lorca and the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén. He always emphasised the importance of clarity and simplicity of expression, whether in teaching or translation.

It is perhaps through his choice of translations that he was able to express his humanitarian beliefs:

“I translate the things I believe in,” he says. “And I want to make it available to everyone. If the writer inspires me in their ideas, then I will translate them.”

“My translation is always trying to work against intolerance. The tide of intolerance is very strong, but my belief is stronger. Monstrosities such as slavery, for example, I feel we have to make sure that doesn’t happen again.”

Salvador was drawn to writers who ‘gave voice to the voiceless’. He combined simple humanity with depth in his teaching and his writing.

He will be sorely missed by hundreds of colleagues who worked with him in Warwick and across the world.

Evan Stewart 29th July 2019

Salvador’s teaching methods were unique and essentially down to his personality, he had a love of performance so playing the guitar with everybody singing along together were integral to them. He believed that if you wanted to learn something you needed to enjoy it and students always looked forward to his classes once they had got over meeting the teacher who Simon Mayo called “the mad Spaniard". He also believed that if students saw the teacher acting like a bit of a fool they didn’t feel so self-conscious and would not worry so much about making mistakes. He preferred to teach beginners as they were a clean slate and his stamina was amazing – he taught four two hour classes on the first Friday of the academic year and the same again on the Saturday – and each Saturday afternoon during term time he could be found filling the blackboard for the following week and photocopying his handouts, strictly old-school.

During the last three weeks of the academic year he taught an intensive beginners evening class – nominally two hours a night (which usually ran to two and a half hours) , three nights a week. Quite often he got carried away and we’d have to remind him to let his students out for a break. I think at one time or another most academics in Humanities went on this course. His teaching room would be decked out with greenery collected from around for this course and often we’d have to spend hours chasing out bees and other insects from the department.

Arthur Brown 29th July 2019

He was a true gentleman as well as a scholar.

I signed up for Salvador’s Accelerated Beginner’s Spanish course – 3 nights a week for 3 weeks – in the summer term of 2000. What a tour de force it was!

We read, we listened, we spoke, we sang whilst he played the guitar, we had fun … and we learned lots.

I quickly warmed to Salvador, and his good old-fashioned methods of teaching. I still think of the mnemonic ‘SOCKS’ when I say the phrase ‘Eso si que es” in Spanish. Totally memorable!

Salvador trained us to shout ‘¡Mas vale tarde que nunca!’ at anyone who turned up late for any of his classes. Sounds intimidating, but it was all done with good humour and, oddly enough, we were rarely late for class! I had to be at the University of Reading on the day of his final class, and drove like a madman to get back to Warwick in time!

Salvador referred to Cervantes’ “Don Quixote” so many times during the 3 weeks of the course that I went out and bought a copy of the novel and read it – in English – from cover to cover. That’s a measure of the impact the man had on me.

As I say, he was a true gentleman as well as a brilliant teacher. He addressed me as ‘Don Pedro’ from the very start – I think because I had registered as ‘Dr Peter Corvi’ for his course. I went off to Reading for 3 years at the end of that summer, returning to Warwick in Oct 2003. I ‘bumped’ into Salvador on a number of occasions after that, always to be greeted with “Buenos dias, Don Pedro. ¿Que tal?“ I wouldn’t be surprised if he remembered the name of every single student he had ever taught.

I was so happy to see him receive a WATE Lifetime Award when he retired from the University in 2008. Still the only person to do so, as far as I’m aware.

I’m sure he is Heaven now, enjoying the company of his mythical hero, the ‘ingenious gentleman’ of La Mancha. They’re probably singing “Caminando por la calle …” right now.

Peter Corvi 14th August 2019

To be invited into Salvador’s apartment above Cannon Park, close to the University, was to be confronted by an eclectic mass of artefacts, mostly paintings, accumulated from auctions and car boot sales, adorning every inch of the walls of his living room and beyond. Other numerous and interesting objects covered surfaces of the furniture, most of which had been similarly sourced. These were the accoutrements of an extrovert and widely loved character. Here he lived eccentrically alone, but he often entertained. Most evenings would see casual visitors, often campus friends including students. Occasionally he would invite people, on at least one occasion including the Vice-Chancellor Jack Butterworth and his wife Doris, to a carefully prepared meal. For a few years I was a close neighbour and was able to enjoy these occasions of warmth and often hilarious entertainment.

Salvador was a gifted guitarist and singer and loved to entertain. These gifts served well within his lectures but also elsewhere within the University. He was a keen member of various university choirs over the years. For some years I organised the annual University Senior Tutor’s Ball and Salvador was an automatic choice as a popular turn in the cabaret.

Recently I attended the Funeral Mass of Monsignor Louis McRaye, the first Roman Catholic Chaplain of the University in St Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham. Like me, Salvador had been a close friend of Louis. I left Warwick nearly 25 years ago and I had hoped to see a number of old friends from Warwick at the Funeral Mass, possibly including Salvador. Instead I learnt of his passing from a mutual friend. As for many others, this filled me with a great sadness.

The University was served exceptionally well by Salvador over several decades. He was an outstanding and internationally acclaimed teacher. He published much translated and original work. He took an enthusiastic part in University life, including being one of the residential sub-wardens in his early years at the University. He enjoyed the affection of many, many friends across the campus. I was very lucky to be one of those.

Alan Gibbons 2nd September 2019

Salvador loved creating nicknames. Nicknames were no doubt helpful when familiarizing himself with new faces. But they were also about fun and language, often both together. Those are the traits that I associate most with Salvador and they fed into his classes, which were fast-paced and exuded vivacious spontaneity. If you wanted to learn about how to ask for a return train ticket, this wasn’t the place for you. Salvador was about poetry, wordplay and performance.

Salvador loved creating nicknames. Nicknames were no doubt helpful when familiarizing himself with new faces. But they were also about fun and language, often both together. Those are the traits that I associate most with Salvador and they fed into his classes, which were fast-paced and exuded vivacious spontaneity. If you wanted to learn about how to ask for a return train ticket, this wasn’t the place for you. Salvador was about poetry, wordplay and performance.

Here are some brief samples from my notes from those classes, which I’ve kept: Lesson 1(!): ‘Valencia es la tierra de las flores, de la luz y del amor’; Lesson 2: ‘no hay mal que cien años dure – there is no ill that lasts a hundred years’; Lesson 3: ‘pecar – to sin’; Lesson 4: ‘¡estoy loco de amor por ti! – I am madly in love with you’; Lesson 6: ‘sólo sé que no sé nada – I only know that I know nothing – Socrates’.

My notes are littered with extracts from poems, phrases, morals and cartoons. I often joked that when I arrived in Argentina after graduating I could speak about my lost soul with a certain confidence but struggled to say what I had bought in the supermarket the day before. The method, in any case, was hugely effective: Salvador’s passion for the Spanish language rubbed off on me and many others – ‘infectious’ was how a friend of mine in the same class recently described it.

Salvador also showed me a great deal of generosity of spirit. In particular, he had no business co-translating a long Romantic Spanish poem with a third-year undergraduate but he did so, in his own time, with complete dedication. And though we wrestled over word choices and line structures, he never imposed his considerable expertise on me – it was always simply about finding the right choice for the task in hand.

I hadn’t seen Salvador for many years before he died and when I heard by chance from a colleague that he’d passed away I wished immediately that I’d taken the time to visit him and catch up. But I know that from time to time, as I sometimes do, I’ll pull one of his translations off the shelf and spend a few minutes sharing his love for language.

James Scorer 9th October 2019

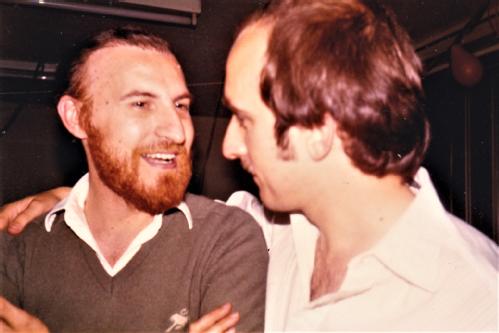

I came across your page on Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres and was sorry to see he had passed away in 2019 (I had already heard we had lost Calum MacDonald and Alistair Hennessy). I read Comparative American Studies (CAS) at Warwick from 1981 - 1984 and undertook Salvador's crash-course in Spanish in the first year. I recall returning from the Christmas break having grown a beard, from which point he would address me as 'El lobo'. That is, until he bumped into me again one morning arriving on campus by bike wearing my yellow waterproofs; after that he would hail me as 'El lobito amarillo'. He was a great teacher and a great character. I've attached a picture of Salvador and myself at the CAS graduation party in June 1984.

I came across your page on Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres and was sorry to see he had passed away in 2019 (I had already heard we had lost Calum MacDonald and Alistair Hennessy). I read Comparative American Studies (CAS) at Warwick from 1981 - 1984 and undertook Salvador's crash-course in Spanish in the first year. I recall returning from the Christmas break having grown a beard, from which point he would address me as 'El lobo'. That is, until he bumped into me again one morning arriving on campus by bike wearing my yellow waterproofs; after that he would hail me as 'El lobito amarillo'. He was a great teacher and a great character. I've attached a picture of Salvador and myself at the CAS graduation party in June 1984.

Jeremy Isaac 2nd June 2021