Sanctuary of Dionysus, Athens

Archaeological Development

The site was first excavated by the Greek Archaeological Society in 1838, after which periodical efforts were made throughout the rest of the 19th century.

There isn't much evidence that tells us around when Dionysus' cult was introduced to Athens. However, the sanctuary of Dionysus, in which the famous theatre is located contains the remains of two temples. The first of these two is dated to around the 6th century BC, whilst the second of which is dated to around 350 BC.[1]

Theatre as we would recognise it was thought to have originated around the time of Thespis, around 530 BC. According to ancient sources such as Aristotle, he was the first person to appear as an 'actor' on stage, and communicate with his chorus in character. The popularisation of acting competitions around this period probably prompted the move from performances in the Agora, to a more permanent area that we now know as Dionysus' sanctuary. The relationship between Dionysus and literature strengthened the god's association with the area, prompting the growth of the Dionysia in honour of him.

The theatre itself is thought to have permanent wooden seating from around 498 BC.[2] The move to a more permanent stone seating in the first half of the 4th century BC is thought to have been under the influence of the Athenian politician, Lycurgus. As the treasurer for the city's finances it seems that the theatre's refurbishment was under his watch during this period.

Gods/Heroes

Dionysus Eleuthereus -

Dionysus Eleuthereus, or the 'The Liberator,' Worship of the deity is thought to have spread during the rule of Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. Worship of the god was originally a rural festival in the ancient city of Eleutherae, in Attica.[3] This rural version of the festival was held in winter, during the month of Poseidon.

Dionysus himself is traditionally associated with nature and performance; specifically relating to wine and ecstasy. He's typically depicted with satyrs, his animalistic servants, whom revel in wine and other aspects of debauchery. His association with wine and its resulting inspiration meant the god was also honoured in relation to literature. During symposiums, where poetry was performed amongst aristocratic drinking, and the performance of theatre at his namesake festival, the Dionysia, the god was honoured as the chief influence. He is first mentioned on a Linear B tablet from the 13th century BC, showing that he was worshipped in the Mycenaean period.[4]

In Mythology practice is said to have moved to Athens after Eleutherae chose to become part of Attica. They then brought a statue of Dionysus to Athens, which the Athenians promptly rejected. Dionysus then punished the Athenians with a Plague affecting the genitalia of men. The plague was alleviated after the cult was accepted by the Athenians, who recorded the incident through carrying phalloi during the procession.

Ritual Activity

Dedications-

In the rural form of the procession, at Eleuthereus, people would carry various objects, such as baskets (kanephoroi), loaves of bread (obeliaphoroi), jars of water (hydriaphoroi) and wine (askophoroi), and 'phalloi' (phallaphoroi). A reenactment of the rural procession was known to take place as part of the City Dionysia.[5] The processions travelled through Athens, out to a temple on the road to Eleuthereus where it was briefly 'dedicated,' and was then escorted back to Athenian temple. This act sought to honour the original transference of the Dionysian statue from Eleuthereus.

Sacrifice-

At the temple on the road to Eleuthereus a sacrifice was offered in accordance with honouring the statue's original home. It's debated upon which day of the Dionysia this took place within; being part of the large, first day procession, or was performed before the festival had even taken place.

In addition to this, bulls were sacrificed at the temple in the Theatre of Dionysus at the end of the procession.

Festivals-

This particular sanctuary was the central focus of a number of Athens' famous Theatrical festivals:

1) The Dionysia: an annual, panhellenic festival associated with Dionysus which involved a procession, music, and a set of tragedies to which the best were awarded prizes.

2) The Lenaea: a far smaller festival honouring Dionysus that took place in January. Due to its smaller size this festival was largely just attended by Athenians. Initially this festival took place 'the Lenaion,' but was later moved into the city by the mid fourth century BC. During the same period, in 440 BC, comedic plays were introduced to the Lenaea, as were tragedies ten years later[6] Comedy featured more heavily in this festival and prizes were awarded to playwrights, as was done during the Dionysia for tragedians.

Rules and Regulations

Since the sanctuary's use was mainly associated with the Dionysia, most of the rules and regulations we have are associated with general course of practice during the five day festival:

The first day was reserved for the procession from the Keramaikos, up through Athens to the Sanctuary of Dionysus on the southern slop of the Acropolis. As I’ve previously stated Phalloi, baskets, water, wine and the wooden statue of Dionysus Eleuthereus were all carried in this procession. Upon reaching the agora, attendees would begin the 'kōmos' dance. This was designed to work the drunken revellers up in to a frenzy, or 'ecstasis' before the festivities. Following this, the crowd would move through the street of tripods, which displayed the awarded monuments to previous funders of winning playwrights. The procession ended at the temple of Dionysus next to the theatre where bulls were sacrificed, and a feast was held for everyone in Athens. Throughout the feast and processions would have been musicians and poets performing their various arts for the attendees

Although there is some disagreement of the order, and on which days the events occurred, it is though that on the second day the various plays were announced during the 'Progaon.' In Plato's 'Symposium,' there's a theatrical account of a progaon for the Lenaea. From this account, it seems as if each performing playwright stood with his actors and announced the subject of the plays he would present.[7] During this event, notable citizens who'd served Athens well during the year were also acknowledged. During the Peloponnesian war, children that had been orphaned as a result of the conflict were paraded infront of the gathered crowd and were subsequently taken care of by the state. Furthermore, member states of Athens' Delian league had their donations dragged in front of the crowd, reminding them of their support for Athens during the Peloponnesian war.

The following three days of the festival were set aside specifically for the performance of plays in the Theatre of Dionysus. Three tragic plays were performed during a day, which were followed by a bawdy Satyr play to round the day off. These plays were judged by notable citizens, thought to be prominent Athenian generals,[8] who chose the best of the playwrights. The winner's play was recorded and stored for future use amongst previous winners. Later on the plays of certain winners were given the right to be re-performed by later generations of actors and playwrights. This is why we several surviving plays of winners such as Aeschylus and Euripides, who's plays were stored for the entertainment of future Greeks.

On the fifth day comedies were performed, so as to alleviate the heavy feelings brought on by the Tragedies earlier in the festival.

The festival itself ended with a political meeting of the Assembly in the Theatre, instead of the Pnyx.

Historical Significance

The Sanctuary of Dionysus in Athens played host to one of the largest Theatrical festivals in the ancient world. Its influence shaped the spread of theatre to many other areas of the world and pioneered the genres and format of theatrics that we use today.

Who used the site, and where did they come from?

The site was primarily used by the Athenians during the 'Dionysia' festival held at Athens every year in March. However, Athens also invited other city states to also attend the festival. These states were often part of Athens' empire during the Delian league, and were therefore obliged to attend and contribute to the event.

Holding the event in March also meant there was generally good sailing whether when the festival was held. This gave the opportunity for even more city states to attend from even further away, and conveniently prevented Athens' pledged city states from not attending.

This meant that, early on it was more likely to be just Athenian citizens who attended the festival. But later one, once Athens' power had grown, and the festival gained infamy, many different peoples from around the Mediterranean attended.

Select Site Bibliography

Prinary Sources

1) Plato, 'Symposium.' Plato In Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9. trans. H. N. Fowler (Cambridge: Harvard Uniersity Press)

Secondary Sources

1) Dinsmoor, W. B. (1950) The Architecture of Ancient Greece. (London: B. T. Batsford)

2) Sourvinou-Inwood, C. and Parker, R. (2011). Athenian Myths and Festivals. (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

3) Goldhill, S. (1987). 'The Great Dionysia and Civic Ideology.' The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105

Websites

1) Perseus Digital Library 4.0, ed. G.R. Crane - http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/ Accessed 28 December 2014

2) Encyclopaedia Britannica - http://www.britannica.com/ Accessed 22 December 2014.

Footnotes

1 Perseus Digital Library 4.0, ed. G.R. Crane. Athens, Theatre of Dionysos. Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/artifact?name=Athens%2C+Theater+of+Dionysos&object=Building. Accessed 28th December 2014

2 This date supports the development from early influences such as Thespis in 534 BC, after whom we see a popularisation of theatrical performance. In addition the curved wall which remains of the seating is from 600 BC at its earliest estimate. See Dinsmoor, W. B. (1950). p.120 and second footnote.

3 Sourvinou-Inwood, C. and Parker, R. (2011).

4 Encyclopaedia Britannica. Dionysus. Available at: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/164280/Dionysus. Accessed 22 December 2014.

5 Goldhill, S. (1987). In The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105: p. 59

6 Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2014). Great Dionysia. Available at: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/243182/Great-Dionysia. Accessed 27 December 2014.

7 Plato, Symposium 194aff

8 Ten generals were known to pour libations before the tragedies were performed, but is unclear how specific their other invovlements in other aspects of the festival were. See Goldhill, S. (1987). In The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105: p. 60

Location

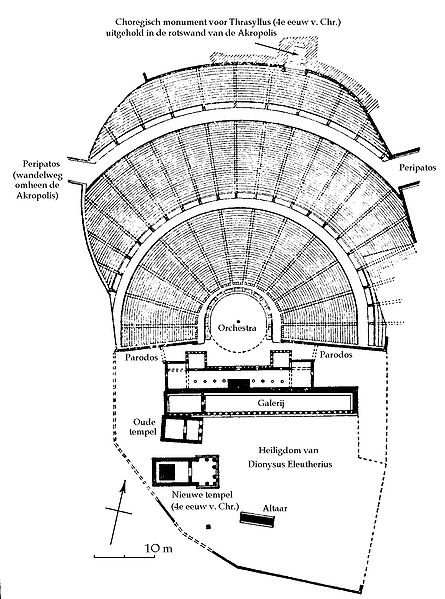

The Sanctuary of Dionysus was located on the southern slope of the Acropolis of Athens, in modern day Greece. The sanctuary of Dionysus incorporated the whole area of Athens' famous theatre. The seats themselves were wooden for a large part of Athenian history, but the temple of Dionysus itself was a fairly small, permanent stone structure behind the stage. The picture below shows the temple during the theatre's early period.

Please add the location here. Also, search for it on Pelagios (click here) and add a link to "further information" about the place.

You might even want to embed a map to show it within the context of other archaeological sites from vici.org, like below. To find out how to do this, see the further instructions page.

Site Plan