The Mysteries of Eleusis - Becca Battles

This project was undertaken through the generous support of the University of Warwick Undergraduate Research Scholarship Scheme [URSS].

The Mysteries of Eleusis - Becca Battles

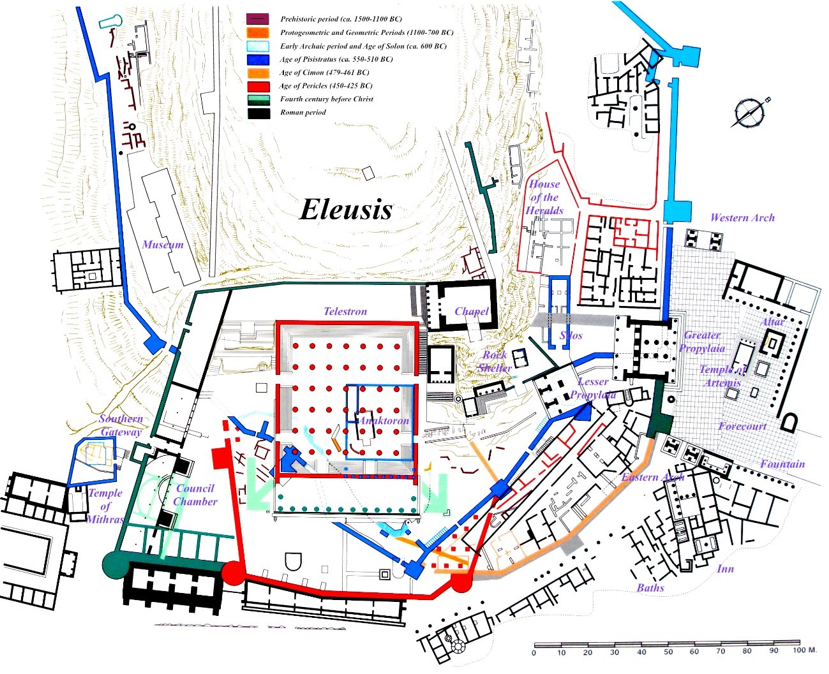

Site map

Abstract

As part of my Undergraduate Research Scholarship Scheme project, I travelled to Athens, Greece to undertake research on the Eleusinian Mysteries. Experiencing the site first-hand is invaluable to researching Greek religion as the geography of the site largely contributes to the spirituality and sensation of the cult. I was able to undertake my own modern pilgrimage mirroring the ancient practice, starting at the Sacred Way in the Kerameikos, travelling along the sea, and arriving at the gates to the sanctuary. In this report, I will explore the contributions of experiencing the sanctuary first-hand and the evidence in Athens.

Introduction

Located 18km Northwest from Athens, the site of Eleusis lies next to the sea and was home to one of the most influential cults of the ancient world. The cult is believed to have originated from Mycenaean practices concerned with agricultural rites and was later developed into the Mysteries of Eleusis. The cult honoured Demeter, Kore (Persephone), and Triptolemos meaning the cult had connections with agrarian and chthonic worship (linked to the powers of the earth and the Underworld).[1]

The origin of the cult is told in The Homeric Hymn to Demeter. As Demeter wanders around the world looking for her daughter after she was abducted by Hades, she arrives at Eleusis and was taken in by the royal family. After a failed attempt to immortalise the infant prince Demophoon, she becomes enraged and hides, causing a famine. In order to placate the goddess, the Eleusinians build her the sanctuary of Eleusis and Demeter later bestows ‘the secrets of the Mysteries’ on the princes. Additionally, Demeter teaches the Eleusinian prince, Triptolemos, the secrets of agriculture which he then spreads throughout the world.

This account of the creation of the rites provides us with an invaluable insight into how the Greeks understood and conceptualised the Mysteries. Whilst the rites and initiation into the cult largely remain secret, we can understand that agriculture and chthonic worship were central to the practices. Furthermore, the significance of the cult is highly important to our understanding of its function in the Mediterranean. The cult is believed to have originated from Mycenaean practices and was destroyed in 396AD when it was sacked by Arian Christians. Throughout this extensive period, the cult was highly regarded and influential in both politics and religion, having the most powerful people (from tyrants and Roman emperors) as initiands. In this report, I will explore the site itself, the rites, along with the perspective from Athens and significant artefacts.

The Site

The sanctuary of Eleusis lies at the North end of the Saronic Gulf in the Thriasian Plain, surrounded by the mountains of Attica. The landscape is dry and rough, covered in small trees and wild cacti, and has a refreshing air due to the sea breezes. Travelling from the centre of a major city like Athens to the sanctuary provides a drastic difference in environment and geography that helps emphasise the otherness of the site. This difference would have also been noticed by the ancient audience. Moving from the centre of a busy, close environment, travelling along the sea towards the plains and mountains of the Attic shore helps create the otherworldly nature of the sanctuary.

Figure 1 Sanctuary entrance courtyard.

Figure 2 View from top of tiered seating.

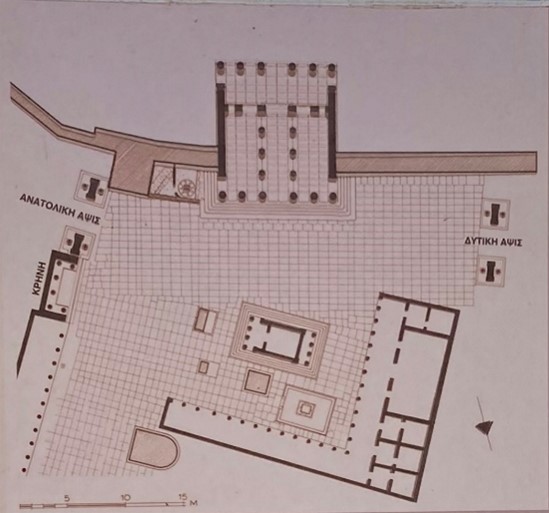

Figure 3 Map of Courtyard (from plaque on site)

The modern site of the sanctuary is a well organised network of stone fragments and wooden walkways. The plaques provide diagrams and descriptions of the structures which now are fragmented stones revealing only floor plans. A lot of the site has been buried by soil and sediment, resulting in multiple deep excavated caverns revealing the buried structures.

Figure 4 Excavated structures.

Figure 5 Excavated structures.

The vast complex starts at the entrance courtyard with the Greater Propylaea lying at the front. The courtyard includes a fountain, a temple to Artemis Propylaia (literally ‘Artemis in-front of the gates’) and Poseidon Patreios (‘Father Poseidon’), and an Eschara (a large altar used to sacrifice and grill meat to the chthonic gods) built in the Roman period. To the left of the Greater Propylaea lies one of the most sacred and important sites of the sanctuary, the Well of the Fair Dances. This is understood as the well that Demeter rested on, mourning the loss of her daughter, when she was visited by the Eleusinian princesses.[2] By placing the Greater Propylaea next to this monument, the sacredness of the site becomes instantly evident to the visitor (and initiate). This is a site visited by the honoured goddess and is recorded in her most popular mythology.

Figure 6 The Greater Propylaea.

Figure 7 The Well of the Fair Dances.

You are then funnelled through the Greater Propylaea to the Lesser Propylaea and the silos dating from the Peisistratid and Periclean period (mid-6th to mid-5th Century BC). After climbing the small incline through the Lesser Propylaea, the Ploutonion lies on the right. The Ploutonion was housed in a cave carved from the hill above, which mirrors the myth of Hades abducting Persephone and re-entering the Underworld through a cave. Similar to the Well of the Fair Dances, by having these sites that reference the Homeric Hymn to Demeter it elevates the significance and sacredness of the site, solidifying the importance of the cult in the initiate’s mind.

Figure 8 The Lesser Propylaea.

Figure 9 The Ploutonion

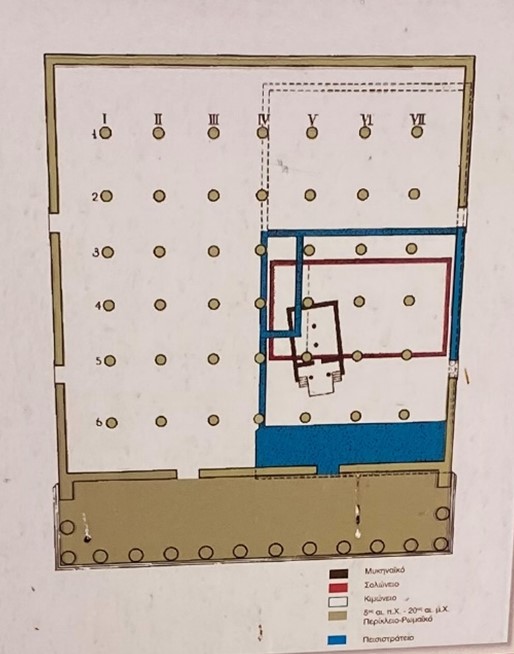

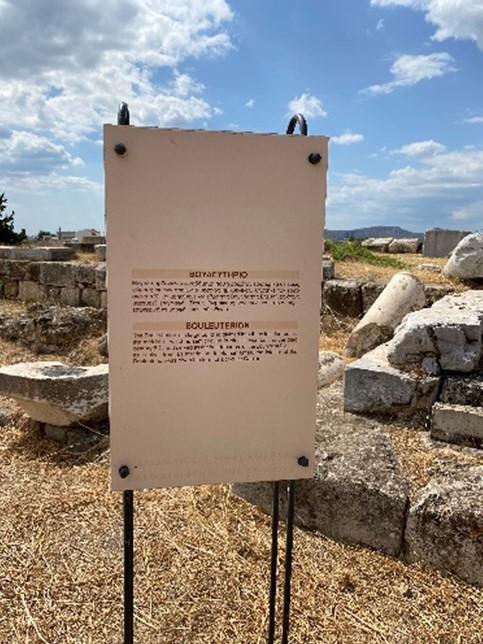

After passing the Ploutonion, you arrive in the Telesterion. Since the visitor has been funnelled through the relatively small walkway, it helps exaggerate the size and grandeur of the space. To the right lies a large, tiered seating area carved into the rock where the initiates would be seated. The space was expanded throughout history due to the increasing demands on the sanctuary with the final modifications being built by Marcus Aurelius in 170AD after a fire. Figure 14 shows how the Telesterion was increased over the centuries. The grand seats and massive space impresses on the visitor the influence of the sanctuary which demanded such grandeur and numinosity. In the centre of the Telesterion was the ‘Palace’ (Anaktoron). This housed the sacred objects and only the Hierophants, male high priests, could enter. On the left end of the Telesterion lies the Stoa of Philo, an architect and major benefactor of the sanctuary in the 4th Century BC. Directly across the Telesterion to the left is the Bouleuterion, the main council chamber for the Eleusinian Council. This helps us imagine that this area of the Telesterion was the main hub of the sanctuary where the organisation and management of the Mysteries was conducted.

Figure 10 Telesterion Tiered Seating.

Figure 11 The Palace (Anaktoron).

Figure 12 Telesterion Left side (Towards Stoa of Philo).

Figure 13 Remains of the Stoa of Philo.

Figure 14 Map of Telesterion (from plaque at site)

Figure 15 The Bouleuterion (plaque from site)

Passing through the Telesterion, you arrive at the South Gate. From this side of the sanctuary you can see the sea lying down the hill. The South Gate was the harbour entrance to the sanctuary and lies on the south of the Lykourgan wall enclosure (4th Century BC), with the original Peisistratid entrance (6th Century BC) lying to the West.

Figure 16 View from South Gate towards the sea.

Figure 17 View from South Gate towards the Telesterion.

Outside of the sanctuary wall lie multiple buildings including the priestess’ house, a temple to Mithras (a popular Roman god), Roman cisterns, and a gymnasium. To the left of the main entrance lie various inns and baths used to accommodate initiates and other visitors. Between the inns and the Greater Propylaea lies the East Triumphal arch. Two Triumphal arches in the East and West were built by Antoninus Pius in the 2nd Century AD and marked the Roman forecourt to the Greater Propylaea.

Figure 18 Antoninus Pius East Triumphal Arch.

Figure 19 Pediment of Triumphal Arch.

The sanctuary includes multiple levels of history as benefactors built, expanded, and modified the functions of various buildings. We can best see this in the site map on the first page, the colours represent the different periods in which those structures were added or reconstructed. As stated above, the buildings range from the Peisistratid period to the various additions made by Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. This resulted in the sanctuary becoming a mixture of various histories and cultures all working together to keep the significance of the cult up to date. This continuous benefaction throughout history helps us recognise the importance of the sanctuary. The cult and sanctuary remained central to religion in Greece despite the varying political disturbances, and was instead recognised as an important site to be seen as a benefactor of.

The Rites

There were the two types of Mysteries worshipped at Eleusis: The Lesser Mysteries and the Greater Mysteries. The Lesser Mysteries were performed in Anthesterion, the 8th month of the ancient Greek calendar around February/March. Whilst there is little information for the Lesser Mysteries, we know that it was held on the East bank of the river Ilisos and involved sacrifices and dancing.[3] Once they had completed this ritual, the individual became a mystai (initiate) and was now worthy of being initiated into the Greater Mysteries.

Before addressing the Greater Mysteries, we must first understand the etymology of certain terms associated with the cult. The word ‘mystai’ and ‘mysteria’ originate from the stem mystes meaning ‘to close/shut’, especially within reference to closing one’s eyes.[4] This means that the term mystai literally translates to ‘the closed eyed’, as they have their eyes closed to the truth of the Mysteries. This is imagined in the climax of the rites when the initiates are blindfolded. Once the initiates have completed the rites, they become epoptes who have seen the truth.[5]

The Greater Mysteries were held during Boedromion, the 3rd calendar month around September/October, and lasted for 9 days. The rites started on the 14th of Boedromion when the sacred objects (hiera) were transported from Eleusis to the Eleusinion, a temple at the base of the Acropolis. ‘The Gathering’ (Agyrmos) was on the 15th, the Archon Basileus (the chief magistrate especially involved with religious rites) gathered everyone at the Poikile Stoa and proclaimed the start of the rites. All Greeks could participate, unless they had been convicted of murder, and later in the 5th Century, if they were ‘impure of mind and soul’.[6] On the 16th, the initiates would travel to the sea and ritually purify themselves by washing a piglet in the sea. Finally, on the 17th they held sacrifices in the Eleusinion and the ‘Epidauria’, the festival for Asklepios, the god of medicine, was held on the 18th.[7]

The procession started on the 19th. This followed the Sacred Way beginning in the Kerameikos, travelling along the sea to arrive at the sanctuary, the modern motorway now follows this route. The initiates would wear festive clothing and swing branches called bacchoi. Once the procession arrived at Eleusis, there would be sacrifices accompanied by singing and dancing.

On the 20th, the Archon Basileus led the most important sacrifice to Demeter and Persephone on the altar of the Two Goddesses outside the Telesterion. The initiates would then drink kykeon, a drink of barley and pennyroyal. Kykeon has been a subject of scholarly debate over its psychedelic effects on the drinker and is argued to be central to the personal, otherworldly experience of the mysteries. The rites on the 20th/21st are debated, however we recognise there were 3 elements of the rites. The Dromena (‘Things Done’) believed to be a dramatic re-enactment of the story of Demeter and Persephone. This re-enactment most likely happened outdoors within the safety of the sanctuary walls. It is theorised that the initiates were blindfolded (relating to the etymology of mystai) and searched for Persephone. This was to impress the sorrow, confusion, and fear of Demeter on the initiates as they wandered blind outside the Telesterion. The doors to the Telesterion would then be opened, a brilliant bright light to express the joy of the return of Persephone.[8]

There was also the Deiknumena (‘Things Shown’) in which the Hierophants displayed the sacred objects, most importantly the hiera, argued to be the baby Ploutos and an ear of corn.[9] The Legomena (‘Things Said’), were most likely a commentary that accompanied the Deiknumena. These rites were named the Aporrheta, ‘The Unrepeatables’, as the initiands were sworn to secrecy to never reveal or describe the rites. The penalty for disclosing the Mysteries was death, such as Athens placing a bounty on Diagoras’ head as punishment for him discussing the rites.[10]

The nature of this secrecy has been questioned by scholarship as they analysed the quote by Aristotle stating, “The initiates are not supposed to learn anything but rather to experience and to be disposed in a certain way, that is, becoming manifestly fit/deserving’’.[11] This quote implies that the knowledge of the rites themselves is not central to understanding their importance, but rather it is the experience that makes them special. Clinton convincingly argues that the rites were kept secret as if they were public knowledge it would trivialise them.[12] It is the experience of the rites, the wandering blind and joy in the sudden light, that makes it extraordinary and a fundamentally personal experience.

The Entheogenic theory argues that this personal experience was induced by the psychedelic effects created by the kykeon. It argues that by drinking kykeon, the initiates were able to hallucinate these sacred scenes to create a personal revelation of the Mysteries. [13] Sansonese developed this theory further to argue that alongside these psychedelic agents, breathing techniques may have been used to effect the initiates nervous system to place them in a trance.[14] However, the Entheogenic theory has been convincingly countered by Cosmopoulos. He states that the sheer number of initiates, 2000-3000, attests against this theory, and reminds us that the Entheogenic theory is not supported by evidence.[15] Therefore, rather than a psychedelic induced trance, the rites themselves were sufficient enough to impress upon the initiate the important transition from sorrow and fear to joy that was central to the rites.

That night there was an all-night feast (pannychis) where the initiates would dance in the Rharian Fields, believed to be the first field in which wheat was grown. On the 22nd, they honoured the dead by pouring libations. The Mysteries ended on the 23rd and the initiates officially became epoptes.[16]

The literary sources for the Greater Mysteries are limited and problematic as we are reliant on writers such as Clement of Alexandria, Hippolytus of Rome, and Arnobius of Sicca.[17] These accounts are often written later and could be describing later additions to the rites, or could be detailing rites held elsewhere. Furthermore, they are often Christian accounts and therefore hold bias against ancient Greek cult practices, often adding and exaggerating the sexual nature of the rites.[18]

The Eleusinian Mysteries and its rites were associated with agriculture, the Underworld, and life after death. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter provides an aetiology for the cult and its associations with agrarian and chthonic worship. Agriculture is central to the Homeric Hymn as Demeter causes a famine after being offended by the Eleusinian royal family. As a result of this, she teaches Triptolemos the secrets of agriculture so that mankind would know how to farm. Furthermore, the Homeric Hymn focuses largely on the Underworld and life after death due to the abduction and marriage of Persephone. Once Zeus allowed Persephone to return to her mother in order to stop the famine, Persephone must return to the Underworld for 3-4 months a year. This results in Persephone embodying the transition between life and death as she transgresses this boundary annually. This is explicitly central to the Greater Mysteries as the initiated are believed to have a better prospect for the afterlife. The rites were understood as taking the fear away from death to instead leave joy, shown in the climax of the rites when the initiates moved from fear and sorrow to joy and relief. We can understand the approach to these beliefs in ancient sources. Pindar Fr. 121 states “Blessed is he who having seen these things had gone under the earth; he knows the end of life; but he also knows the god-given beginning”.[19] And Sophocles states in Fr. 837 “Thrice- blessed among the mortals are those who having seen these sacred rites enter Hades: from them alone there is life, but for the others all is evil”.[20] These two fragments provide us with evidence to how the Eleusinian Mysteries were conceptualised in Greek thought as a personal, sacred experience.

Athens

Figure 20 The Sacred Way in the Kerameikos.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were highly influential and held great importance in Athens. The Sacred Way started in the Kerameikos, the Kerameis deme housing the potters district and main cemetery of Athens. In 478BC, when the Themistoclean Wall was built, improvements were made to the route of the Eridanos River which was prone to flooding the area; because of this the ground level is the same as it was in the Classical period. After passing through the Sacred Gate, you encounter the tombs and altars of Classical and Archaic burials. This particularly holds significance in relation to the Eleusinian Mysteries due to its focus on the Afterlife and Underworld. The initiates would be reminded of the importance of the rites they are performing and of their own mortality. It has also been speculated that these funerary monuments continued along the Sacred Way many kilometres towards Eleusis.

Furthermore, we can note the visibility of Eleusis from the Acropolis. As stated previously, the Eleusinion was situated at the base of the Acropolis, marking its importance in Athenian religion and society. Once at the top of the Acropolis, you can see the whole landscape of Athens and the surrounding Attic countryside.

Figure 21 View towards the Sea from the Acropolis Slopes.

To the Northwest you can see the sea and Saronic Gulf, with Eleusis situated on the North coast. Being able to see Eleusis from a distance emphasises the proximity of the cult and helps create a link between the Acropolis, the centre of religion in Athens, and the Eleusinian Mysteries. The connection (both physical and ritual) between Athens and Eleusis through the Sacred Way and Acropolis helps us recognise the significance the Eleusinian Mysteries held in Athenian religion.

The Eleusinian Mysteries also held political and military importance. The Mysteries, represented by the Hierophants and Archon Basileus, held great political and social power in Athens. Despite the attitude of general religious freedom in Athens, the Eleusinian Mysteries presented a stricter attitude towards its initiands. As stated before, Diagoras fled out of Athens due to a price being put on his head for allegedly disclosing the Mysteries. This was not uncommon as there have been multiple accounts of various, often politically significant, individuals being accused of profaning or disclosing the rites. These names were inscribed on bronze and stone stelae outside of the Eleusinion.[21] This resulted in the Mysteries having an extremely large and imposing presence in Athenian politics and religion. Furthermore, Eleusis held military significance. There have been multiple inscriptions found both in the sanctuary and the city itself that provide evidence of multiple military units. One inscription from 259/8BC found in the sanctuary states that it was established by Athenian soldiers to honour Sosikrates, the treasurer of the military fund.[22] It is especially interesting that this inscription was set up in the sanctuary as it shows that the site did not have a solely religious purpose but also held social importance in the community. Another inscription found in the city from 325-300BC was set up by Eleusis in honour of the patrol-commander, Smikythion, who had provided Eleusis with patrol soldiers.[23] This military presence was part of the force responsible for the security of the Attic countryside. Therefore we can see that the Mysteries also had a wider impact on the military and politics of Athens.

Artefacts

Firstly, I will discuss artefacts and stone fragments found in the sanctuary at Eleusis. Whilst walking around the site, I was struck by the multitude and size of stone fragments. Some were placed next to their original structures and others were lying waiting to be identified by archaeologists. A lot of these fragments were elaborately decorated with floral motifs and designs.

Figure 22 Stone fragment from entrance courtyard.

Figure 23 Corinthian capital from entrance courtyard.

Figure 24 Stone fragment dating from Roman period depicting wheat and flowers.

Two fragments were particularly striking. Firstly, a stone relief showing two crossed torches. Torches were an important cult object in the Greater Mysteries as they were carried by initiates on the night of the 18th when they re-enacted Demeter’s search for Persephone. By having these crossed torches on a relief, especially the size they are carved, further emphasises the torch as an important motif used in the Mysteries. Secondly, there was a larger-than-life cuirassed bust of Marcus Aurelius. The head, shoulders, and upper body emerge out of a wreath to create a unique and striking impression of the emperor. This bust further highlights the Roman presence in Eleusis. The Roman emperors, especially Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, recognised the importance and popularity of the Mysteries and therefore inserted their presence as to be seen as a benefactor of Greece.

Figure 25 Relief fragment of crossed torches.

Figure 26 Cuirassed bust of Marcus Aurelius.

The Museum of Eleusis holds the most important artefacts found in the sanctuary. It has many vases, pot fragments, and impressive sculptures such as the headless statue of Demeter and a caryatid from the roof of the Lesser Propylaea. Whilst I was unable to see these as the museum was closed, I was able to visit the National Archaeological Museum which holds many artefacts related to Eleusis. The ‘Ninnion Tablet’ is particularly striking and important for our understanding of the Mysteries and its representation. The plaque was discovered in Eleusis and dates from the middle of the 4th Century BC. Small holes in the 4 corners implies that it was hung up in the sanctuary. The scene on the plaque is organised into two rows. At the bottom, Demeter is seated with her sceptre rested on her arm as she receives the procession of initiates led by Iakos, the torchbearer and god of the procession. Below there are the symbols of the Mysteries, a wreathed omphalos and two crossing backhoe. Above, Kore carries two torches and it accompanied by an unidentified goddess. The pediment depicts the all-night feast (pannychis) and all worshippers are crowned and holding branches. Through examining this plaque we can come to understand the motifs of the Mysteries and the experiences of the initiates.

Figure 27 The Ninnion Tablet, 4th Century BC, Eleusis. Representation of the rites and motifs of the Greater Mysteries.

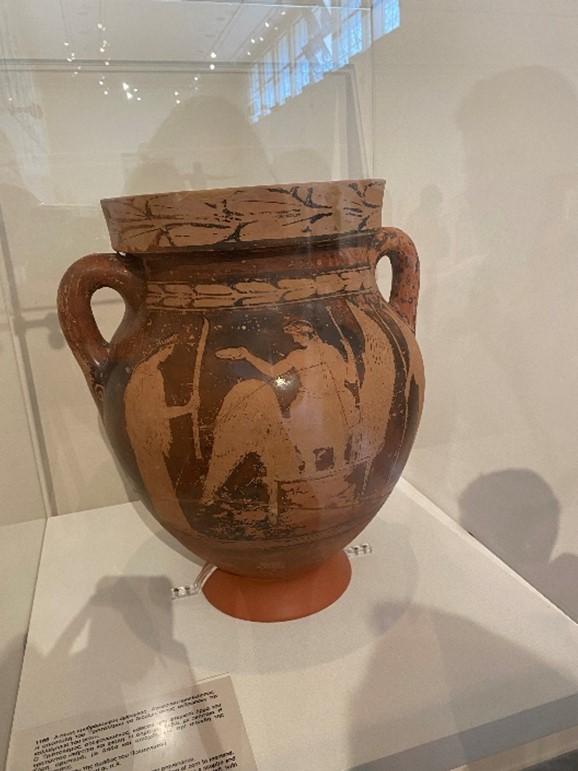

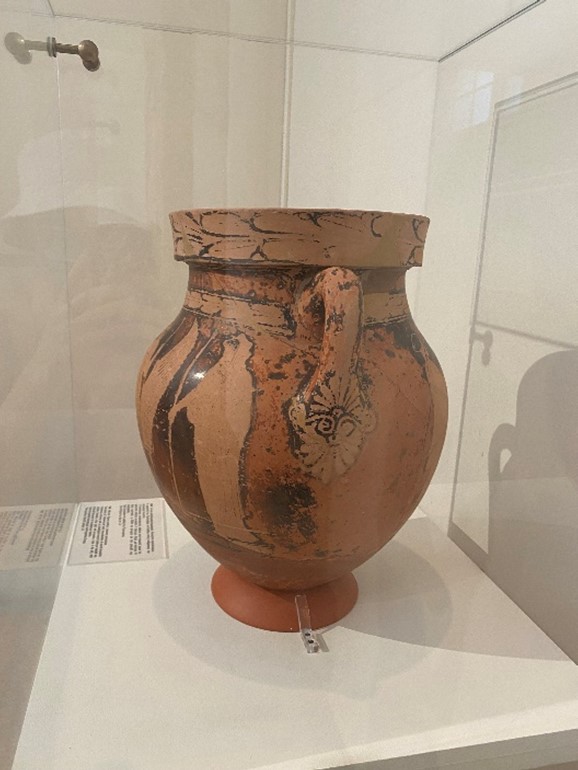

There are also many vases that depict scenes related to the Eleusinian Mysteries and the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. An Attic red Amphora, dating from the last quarter of the 5th Century BC, depicts Triptolemos departing to teach the new agricultural knowledge to mankind. Triptolemos is crowned, seated on his winged chariot, and holds a sceptre and phiale (libation bowl). Demeter stands to the right holding a sceptre, and Kore stands on the left holding a torch and oinochoe (wine jug) to pour a departing libation. This image shows how the popularisation and teaching of agriculture was conceptualised in Greek thought. They imagined the start of agriculture as originating from this scene in Eleusis when Triptolemos was divinely ordered to spread the knowledge of agriculture. This scene is further imagined on a Calyx Krater (a storage vase for diluted wine) from the early 4th Century BC. One side shows an elaborately detailed scene of Triptolemos on his winged chariot surrounded by Demeter, Kore, and a satyr. The other side depicts a satyr and maenad. The presence of satyrs and maenads creates a connection with Dionysiac worship which is not unusual as Dionysus is often associated with Demeter in myth and worship. On this Krater, the painter is most likely commenting on the divine gifts these gods have given humanity: corn and wine.

Figure 28 Attic Red Amphora, 5th Century BC. The departure of Triptolemos with Demeter and Kore.

Figure 29 Attic Red Amphora, 5th Century BC. The departure of Triptolemos (side) with Demeter and Kore.

Figure 30 Calyx Krater, 4th Century BC. The departure of Triptolemos with Demeter, Kore, and a satyr.

Conclusion

Visiting the site of the Eleusinian Mysteries in person, and seeing the associated artefacts, was invaluable to my understanding of the cult. By being able to experience the sanctuary itself, I could come to a fuller appreciation of its importance in Athens and the whole Panhellenic religion. Travelling to Athens made me realise how close and connected Athens and Eleusis were through the visible link created by the landscape and the Sacred Way.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were highly influential throughout both space and time. Surviving for centuries attests to its ability to appeal to both individual initiates and also the greater political organisations of Athens, Greece, and later, the Roman Empire. The study of the Eleusinian Mysteries impacts our understanding of Greek religion and its social, personal, and political influences. It provides us with invaluable insight into how the ancient Greeks understood their gods and what roles they played in their personal and polis life. However, we must remember that whilst the Mysteries held great Panhellenic importance, it was also fundamentally a personal experience.

Notes

[1] Parker (1991) 11-12.

[2] Homeric Hymn to Demeter lines 97-120.

[3] Cosmopoulos (2015)17.

[4] Clinton (2007) 343.

[5] Cosmopoulos (2015) 15.

[6] Cosmopoulos (2015) 18.

[7] Cosmopoulos (2015) 18-19.

[8] Cosmopoulos (2015) 22-23.

[9] Cosmopoulos (2015) 23-24; Parker (1991) 13.

[10] Gagne (2009) 217-218.

[11] Aristotle Fr. 15 trans. Rose = Clinton (2007) 343.

[12] Clinton (2007) 343-344.

[13] Bell (1980) 126.

[14] Sansonese (1994) 195-215.

[15] Cosmopoulos (2015) 21.

[16] Cosmopoulos (2015) 24.

[17] Meyer (1999) 18.

[18] Meyer (1999) 18.

[19] Petridou (2013); Pindar fr.121.

[20] Petridou (2013); Sophocles fr.837.

[21] Gagne (2009) 217-218.

[22] E181 Attic Inscriptions Online.

[23] E1130 Attic Inscriptions Online.

Further Reading

Burkert, W (1991) Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical trans. Raffan. J (New Jersey: John Wiley and sons)

Clinton, K (2007) ‘The Mysteries of Demeter and Kore’ in Odgen, D [ed.] A Companion to Greek Religion (Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing) pp.342-356.

Cosmopoulos, M. B (2015) Bronze Age Eleusis and the origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Keller, M. L (1988) ‘The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth’ Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion Spring 1988 Vol. 4 No. 1 pp. 27-54.

Nilsson, M. P (1961) Greek Folk Religion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Parker, R (2011) On Greek Religion (New York: Cornell University Press)

Petridou, G (2013) ‘Blessed Is He, who has seen”: The Power of Ritual Viewing and Ritual Framing in Eleusis (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press)

Wasson, R. G, Ruck, C. A. P and Hofmann, A (1978) The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (New York, London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich)

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter trans. Evelyn-White, G (1914) via Perseus.Tufts.

Bibliography

Bell, J. M (1980) Review on Wasson, R. G, Ruck, C. A. P and Hofmann, A (1978) The road to Eleusis. Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries (Ethno-mycological Studies no.4) pp.126.

Burkert, W (1991) Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical (trans. Raffan, J.) (New Jersey: John Wiley and sons)

Clinton, K (2007) ‘The Mysteries of Demeter and Kore’ in Odgen, D [ed.] A Companion to Greek Religion (Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing) pp.342-356.

Cosmopoulos, M. B (2015) Bronze Age Eleusis and the origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Eliade, M (1958) Birth and Rebirth: The religious Meanings of Initiation in Human Culture trans Trask, W. R (Harvill Press: London)

Foley, H. P (1994) ‘The Mother/Daughter Romance’ in Foley, H. P [ed.] The Homeric Hymn to Demeter: Translation, Commentary, and Interpretive Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press) pp. 118-137.

Gagne, R (2009) ‘Mystery Inquisitors: Performance, Authority, and Sacrilege at Eleusis’ Classical Antiquity (Berkley: University of California Press) pp. 211-247.

Jung, C. G and Kerenyi, C (2002) Science of Mythology: Essays on the Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis trans R. F. C Hull (London, New York: Routledge)

Keller, M. L (1988) ‘The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone: Fertility, Sexuality, and Rebirth’ Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion Spring 1988 Vol. 4 No. 1 pp. 27-54.

Meyer, M (1999) The Ancient Mysteries: A Sourcebook of Sacred Texts (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Nilsson, M. P (1961) Greek Folk Religion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Parker, R (1991) ‘The ‘Hymn to Demeter’ and the ‘Homeric Hymns’’ Greece and Rome vol.38 no. 1 Apr 1991 pp.1-17.

(2011) On Greek Religion (New York: Cornell University Press)

Petridou, G (2013) ‘Blessed Is He, who has seen”: The power of Ritual Viewing and Ritual Framing in Eleusis (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press)

Sansonese, J. N (1994) The Body of Myth: Mythology, Shamanic Trance, and the Sacred Geography of the Body (Vermont: Inner Traditions/Bear)

Images

All pictures taken by Rebecca Battles unless otherwise stated.

Site Map from CWA068_EleusisF.pdf (archaeolink.org), article written by Duff, P via ArchaeoLink.

Also a big thank you to my supervisor, Dr Paul Grigsby, for all your help with the project.