Neolithic Britain

Introduction to the Neolithic Period

The Neolithic period lasted from around 4300 BC down to 2000 BC, so some 6000 years before present. Neolithic means 'New Stone' and so this period is sometimes called the New Stone Age. Famous Neolithic sites in Britain include Avebury, Stonehenge, and Silbury Hill (below).

The Arrival of the Neolithic Culture in Britain

Britain became populated by people with a Neolithic culture by around 4000BC. The island's entire culture changed, incorporating new pottery, tools and funerary practices.

But where did this new practice of farming come from, and what happened to the hunter-gatherers already living in Britain? DNA sequencing at the British Museum has been providing some answers. (You can check out their excellent website here from which some of the following information has been taken).

The culture of farming arrived in Britain some 6,000 years ago (around 4000BC), marking the beginning of the Neolithic period. Previously, in the Mesolithic period (Middle Stone Age) Britain had been home to a population of hunter-fisher-gatherers. This transition to farming marked a huge shift in cultural life in the region. For a long time it wasn't known whether the arrival of Neolithic farming cultures represented a change of practice by the native Britons, taking up these new farming techniques and culture, or if the change revealed the arrival of migrant farmers from continental Europe.

To answer this, Dr Tom Booth of the British Museum and his colleagues looked at the genetics of ancient Britons. Their results published in the scientific journal Nature Ecology and Evolution revealed that as soon as the Neolithic cultures started to arrive, there was a big change in the ancestry of the British population. So the development of farming and these Neolithic cultures seems to have been mainly driven by the migration of people from mainland Europe.

The route to Britain

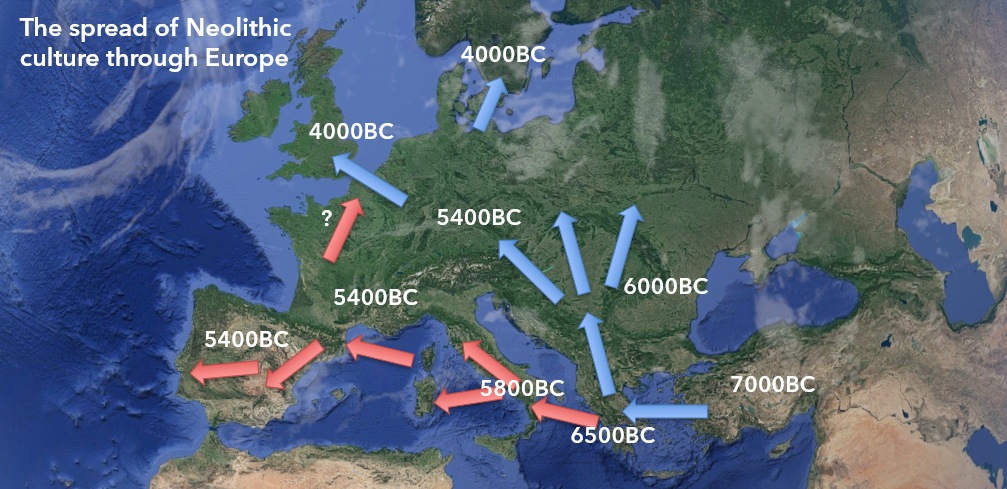

When the original Neolithic farmers left the Aegean and began spreading out across Europe, the population very quickly split into two rough groups that developed slightly different cultures. One group went north along the river Danube and mixed with the hunter-gatherer populations of Central Europe (blue arrows below). A second group took a more southerly route (red arrows) along the Mediterranean before reaching Iberia (Spain and Portugal).

The map above shows the likely route of the spread of farming practice from Anatolia (modern day Turkey) through Europe, arriving in Britain around 4000BC (adapted from Bogucki, The Spread of Early Farming in Europe, 1996).

The earlier Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Britain had ties with those from Scandinavia, but the Neolithic culture shows a mix of both the Central European and Mediterranean traditions - i.e. both the northern and southern groups. As such it is difficult to fully understand where the British Neolithic farmers came from! Especially because although they share parts of both cultures, genetically the Britons seem to be more closely related to the Southern/Iberian group. It is possible that some of the southern group moved up from southern France and maybe Iberia to northern France, where they then mixed slightly with the central European population, before moving into Britain.

Thus we see that the British Neolithic population had significant ancestry from the earliest farming communities in Anatolia (modern day Turkey), and this suggests that a major migration accompanied this spread of farming. Farming itself with its associated Neolithic culture is thought to have originated in the Near East, making its way to the Aegean coast in Turkey and Greece. From there, farming and the specific culture that came with it (such as new funerary rites and pottery) spread across much of Western Europe and eventually to Britain. As the Greek Reporter news site reported these findings, Ancient Greeks Were Britain's First Farmers. A slight exaggeration, perhaps, but with an element of truth in it.

Where did the Original Britons go?

But what about the original hunter-gatherer Britons? It seems that they were not completely displaced. As with many such migrations, DNA evidence shows that as these new farmers were moving through the unfamiliar forests and grasslands of Europe, they were also mixing with the local hunter-gatherers who had already made a living there.

'As this Neolithic population moved west, we can track cumulatively increasing levels of the local hunter-gatherer signatures in the genetics,' says Dr Tom Booth. 'So this wasn't just one population wiping the other out. Instead, they were mixing.'

But the Aegean ancestry nearly always dominates, and this is because farming, with its settled lifestyle and more predictable food sources, allowed people to maintain much larger population sizes.

'This means that even though they were mixing continuously, the hunter-gatherers were always a more minor component in the overall genetics.'

As the farmers moved east to west, by the time they reached Iberia (Spain and Portugal) about 40% of their ancestry could be traced back to the original European hunter-gatherer populations that they mixed with as they moved across the continent.

Crossing the Channel

The Neolithic cultures arrived in northern France, Belgium and Germany - our neighbours across the Channel - around 1,000 years before they arrived in Britain.

Why did it take them so long to arrive in Britain? We don't know. We have evidence that people in that period could build boats and cross the English Channel, so the physical barrier was probably not the problem. One idea is that hunter-gatherer people from Britain were making forays to the continent and gradually coming around to the idea of farming before taking it up wholesale 6,000 years ago. Another idea is that there was an influx of Neolithic farmers at this time.

Dr Tom Booth and his British Museum team found through studying the ancient DNA of six Mesolithic Britons and 67 Neolithic Britons that most of the hunter-gatherer population was replaced by those carrying ancestry originating in the Aegean. As Tom says, 'The best explanation at the moment is that the hunter-gatherer Mesolithic population of Britain just wasn't very high. So the newly arrived farmers could have mixed entirely with the native population but because this was quite small, the hunter-gatherers left little genetic legacy overall.'

What did they look like?

Genetics can also give hints as to what these early people may have looked like. The genetic variants found in the Mesolithic, including that of Cheddar Man and at least one of the Neolithic humans, show that they likely had darker skin than we associate with northern Europeans today. The genetics indicate that these early populations of people were far more variable in their skin pigmentation than has been thought. And the trend towards developing paler skins did not in fact really appear until subsequent further migrations occurred during our next time period, the Bronze Age.

You can find more British Museum Resources on Neolithic Britain here.

Neolithic Warwickshire

While Neolithic sites in Warwickshire are sparse, without obvious star sites such as a Stonehenge, this does not mean that Warwickshire's Neolithic past is not of interest. Neolithic artefacts found in the county include this beautiful polished handaxe (below) identified at Warwickshire Museum as a 6000 year old stone axe.

Neolithic stone axe Stratford Upon Avon

As reported on OurWarwickshire site, this stone axe was discovered by Mr James Schofield in his Stratford-upon-Avon garden. It measures just over 7cm long and 4cm at its widest. Axes like this were used to clear woodland for crops, and for keeping newly domesticated breeds of sheep and cattle.

Polished axes like this one are the first evidence we have of trade in the past. They were produced at large scale stone workings or ‘axe factories’. The stone was quarried and cut to the rough shape of the axe. Each axe was then painstakingly polished to a shiny surface, which would have taken many hours to achieve. This axe is made of an altered volcanic rock and may have come from Borrowdale in the Lake District or from North Wales.

Axes from specific sites have been found all over the British Isles, many miles away from their original quarry site and must have been transported on foot, or on the backs of oxen or ponies, along ancient trackways, before the introduction of wheeled vehicles.