History News

'Unfair' anti–corruption processes, then and now

'Unfair' anti–corruption processes, then and now

The Parliamentary Committee on Standards has published a report on the conduct of former cabinet minister and Tory MP, Owen Paterson, saying that he had breached Commons lobbying rules by making approaches to two governmental bodies on behalf of two companies which employed him as a paid consultant.

The Committee found that Paterson had breached the 2015 Code of Conduct, which upholds the Nolan Principles on standards in public life, on a number of counts. The Code imposes a duty on MPs to avoid conflicts of interest and not to take any ‘fee, compensation or reward’ in relation to parliamentary business. It also requires MPs to ‘always be open and frank in drawing attention to any relevant interest in any proceeding of the House or its Committees, and in any communications with Ministers, Members, public officials or public office holders. The Report concluded that ‘Mr Paterson is clearly convinced in his own mind that there could be no conflict between his private interest and the public interest in his actions in this case’; but the Committee disagreed with his self-analysis and found that he had shown ‘a failure to uphold the Seven Principles of Public Life.’ It recommended that he be suspended for 30 days, something that could in turn trigger the potential for a by-election if sufficient constituents signed a recall petition.

Paterson has denied any wrongdoing and argued his approaches were within the rules because he was seeking to alert ministers to defects in safety regulations. He has also gone on the counter-attack, suggesting that the process by which the Committee came to its conclusions is unfair and had contributed to his wife’s suicide last year. Paterson has found support from other MPs who argue that another committee should be established to investigate whether ‘the current standards system should give Members of Parliament the same or similar rights as apply to those subject to investigations of alleged misconduct in other workplaces and professions, including the right of representation, examination of witnesses and appeal.’ The Commons has now supported this motion, even though it carries a built-in advantage for Mr Paterson, since although the committee would have four Tories, three Labour and one SNP members, the proposed Tory chair, John Whittingdale, would have the casting vote.

All this has resonances with a case from the early 1780s involving another MP, Sir Thomas Rumbold, whose image graced an earlier blog. To be sure, there are significant differences between the cases and the suggestion here is not that the parallels are exact; but there are also interesting echoes in relation to an MP feeling himself unfairly treated by an inquiry into his conduct and in relation to disputed views about the compatibility of private and public interests. Politics is also involved in both cases.

Rumbold held office in the East India Company, one of the leading trading companies of the eighteenth century which had begun to administer large amounts of territory in India and collect taxes there. On 29 April 1782 the Commons voted to support a ‘secret’, select committee’s resolutions condemning his conduct as Company’s governor of Madras (1778-1781), though Rumbold fumed that the verdict of the ‘secret committee’ had become very public and threatened his reputation. A central allegation was that he had abused his position in order to profit from payments made by Indian landowners for settling their leases. Rumbold then became the subject of a parliamentary bill of ‘pains and penalties’ for his allegedly corrupt administration. The bill was a parliamentary process that avoided the need for a formal trial. The bill asserted that the money Rumbold had sent back from India –many thousands of pounds - should be ‘considered proofs of a corrupt acquisition of his fortune’, a sort of early unexplained wealth order.

Rumbold, who had bought a seat in Parliament to protect himself against such attacks, claimed that all the actions that were condemned as evidence of corruption were in fact intended for the good of the East India Company – they were all ‘wise, honorable and just arrangements for the Company’s interests’. Any deviance from the formal instructions was ‘meritorious disobedience’. A defence of Rumbold’s actions argued that he had faced mere ‘insinuation’ about his conduct, the result of antipathies that he thought arose from prejudices ‘against every Eastern Governor who has made large acquisitions to his English fortune’. He resented the insinuation of corruption since it was almost impossible to defeat such smears: ‘it’s the insinuated guilt of corruption that criminates … insinuated corruption is never to end’. The prosecution should prove his misconduct, not insinuate. Rumbold also claimed that the process against him was unfair: he had been treated differently to others and the evidence against him was obtained from unreliable, even bribed, informers. And he resented that due process had been denied to him. He said he ‘could not call that justice which inflicted punishment on a man who had not been heard in his defence’. He considered himself ‘a Political victim’ of his enemies.

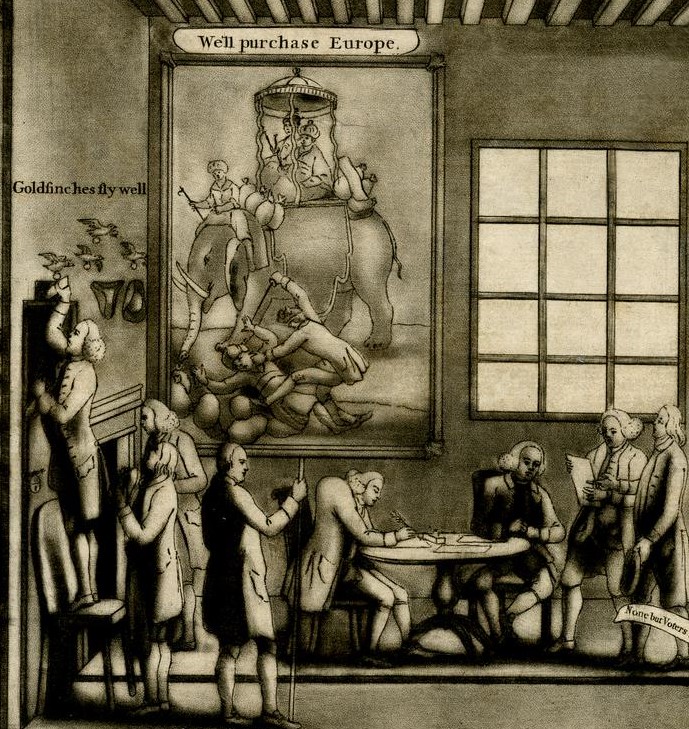

The image is a detail from a satire showing Rumbold's electoral corruption, a decade before the allegations about his malpractice in India. Contemporaries believed that his Indian money also helped to blunt the parliamentary attack in 1782-3.

The bill against Rumbold failed, after being repeatedly postponed until the desire to pass it seemed to have ebbed away, albeit not without suggestions from some that he had bribed the chair of the bill’s committee to achieve this. Even those who thought him guilty had reservations about the proof that could be produced and even an opposition leader, Charles James Fox, thought that the House displayed ‘a real tenderness for the person accused which…..must make it impossible to carry on the prosecution with effect’. The failure of the bill prefigured the much better-known failure of the impeachment later the same decade of Warren Hastings, which was another testament to the power of political interests and connections overcoming a legal case of corruption brought within the existing rules. Rumbold appeared to have won. He was not prosecuted in the courts and was wealthy enough from his Indian gains to build a large house, Woodhall Park, in Hertfordshire.

Yet the issues raised by Rumbold’s career in India (where he was known as ‘Sir Thomas Pillage’) did not go away. Two years before action was taken against him in the Commons, a Commission for Public Accounts had been established and over the course of the early 1780s it made a series of landmark reports which helped to develop standards of conduct that are now codified in the Nolan principles that Paterson is alleged to have breached. Public officials, the reports declared, held public trusts and should not pursue their self-interest; in the place of ‘multifarious Emoluments’ they ought to have ‘one certain salary’; public money and private money ought to be separated out; and the principle that should underlie all public office was the public good.

Mark Knights’ book on corruption in office in the period 1600-1850 will be published on 6 December.