The Secrets of Alchemy

Click here to download the powerpoint for this lecture

Nowadays the term 'alchemy' conjures up images of obsessive, deluded and/or deceitful individuals who used obscure language to claim that they could achieve what we now know to be impossible, namely convert base metals into gold. Certainly there were certainly some early moderns who fitted this description. However it was only in the eighteenth century that the term 'alchemy' gained the starkly negative connotations that it has today. Before then, 'alchemy' was synonymous with 'chemistry' and included a wide range of theories and practices, many of which (including metallic transmutation) were backed up by serious laboratory experiments and by the leading philosophies of the day. Of course, early modern 'chemistry/alchemy' was not identical to the present-day discipline of chemistry. It was an fascinating hybrid of the strange and familiar that historians refer to as 'chymistry.' It was not necessarily opposed to the theories and methods that we associate with the Scientific Revolution. Indeed, it gained new scope and prestige in the sixteenth century and was widely practised in the seventeenth century by 'revolutionary' figures such as Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton.

Questions

What was 'chymistry' in early modern Europe?

Why is Paracelsus an important figure in early modern chymistry?

Why did so many early modern chymists believe that base metals can be converted into gold?

What do modern-day chemical experiments tell us about the nature of early modern chymistry?

Essential Reading

Principe, Lawrence. The Secrets of Alchemy. University of Chicago Press, 2013. Chapter 5 ('The Golden Age') and chapter 6 ('Unveiling the Secrets'). Note: there are quite a few pages in this reading, but it is accessible and well-written. In Chapter 6 there is a long section called 'Chrysopoeia: Deciphering Hidden Knowledge.' You don't need to grasp every procedure that Principe discusses in this section; a rough understanding of one or two of those procedures should suffice to answer the questions.

Further Reading

Newman, William. 'From Alchemy to 'Chymistry'', in CHS3.

Brock, W.H. The Fontana History of Chemistry. Fontana Press, 1992.

Dobbs, Betty. The Foundations of Newton’s Alchemy: Or, ‘The Hunting of the Greene Lyon’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

Linden, Stanton J., ed. The Alchemy Reader: From Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Moran, Bruce T. Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Newman, William. ‘The Background to Newton’s Chemistry’. In The Cambridge Companion to Newton, edited by I. Bernard Cohen and George E. Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Newman, William. ‘The Alchemical Sources of Robert Boyle’s Corpuscular Philosophy’. Annals of Science 53, no. 6 (1996): 567.

Newman, William. Atoms and Alchemy: Chymistry and the Experimental Origins of the Scientific Revolution. Chicago, [Ill.]: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Newman, William., and Lawrence M. Principe. ‘Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake’. Early Science and Medicine 3, no. 1 (1998): 32–65.

Principe, Lawrence. ‘The Alchemies of Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton: Alternate Strategies and Divergent Deployments’. In Rethinking the Scientific Revolution, edited by Margaret J Osler, 201–20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

———. ‘The End of Alchemy? The Repudiation and Persistence of Chrysopoeia at the Académie Royale des Sciences in the Eighteenth Century’. Osiris 29 (2014): 96–116.

Grafton, Anthony, and Newman, William. Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2001.

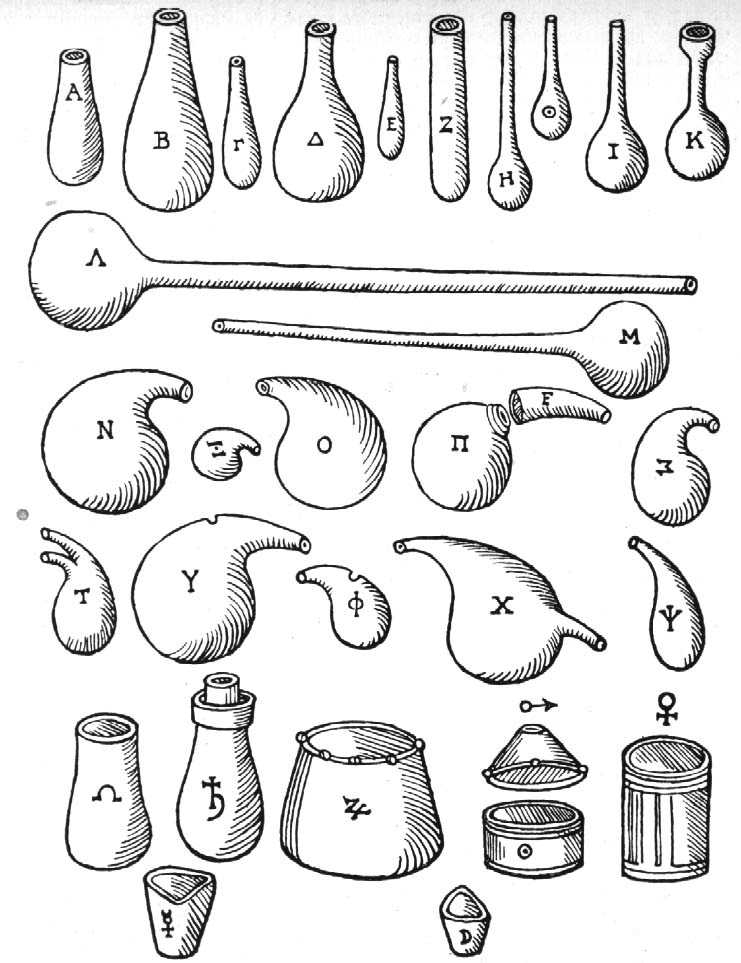

Woodcuts of chemical utensils from Andreas Libavius' Alchymia (1606), usually regarded as the first European chemical textbook.