Week 10: Cataloguing and Collecting

Essential Reading

- Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Chicago, 2012). Chapter 1: A Botanical Reconquista, pp. 17-39; Conclusion: The Empire as an Image Machine: pp. 187-192

- Daniela Bleichmar, Paula de Vos, Kristin Huffine, and Kevin Sheehan, eds., Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, 1500-1800 (Stanford: 2009). Chapter 14: Paula de Vos, The Rare, the Singular, and the Extraordinary: Natural History and the Collection of Curiosities in the Spanish Empire, pp.271-189

Seminar Questions

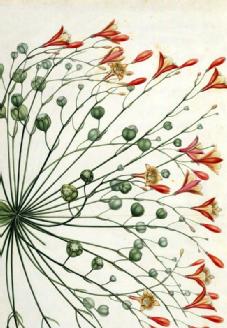

- Consider the following questions posed by Daniela Bleichmar: “Why did Hispanic naturalists and imperial administrators care so much about images— what work did visual materials do for them? What to make of these images, hybrids of art and science, and in some cases of European and American styles? And a methodological question: “How can historians use these materials not only for visual analysis but also as historical sources, treating the visual archive as seriously as the textual archive?”

- What role did curiosities play in the natural history collections of 18thC Spain, why were they sought after? How were these later collecting efforts different from attempts to catalogue/describe/collect New World objects and things in the 16thC?

- How might curiosities be used for political purposes (in the context of 18thC European rivalries), and what role might they play in processes of ‘imperial self-fashioning?’

Further Reading

- Antonio Barrera-Osorio, Experiencing Nature: The Spanish American Empire and the Early Scientific Revolution (Texas: 2006). Chapter Five: Books of Nature: Scholars, Natural History, and the New World, pp.101-127

- Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, ‘Iberian Colonial Science’, ISIS, 96: 1 (March, 2005), pp. 64-70

- José Ramón Marcaida, ‘Rubens and the Bird of Paradise: Painting Natural Knowledge in the Early Seventeenth Century,’ Renaissans Studies, 28:1 (2014), pp. 112-127

- José Ramón Marcaida and Juan Pimentel, ‘Dead Natures or Still Lifes? Science, Art, and Collecting in the Spanish Baroque,’ in Daniela Bleichmar and Peter Marcall, Collecting Across Cultures: Material Exchanges in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Philadelphia, 2011).

- Daniela Bleichmar, Paula de Vos, Kristin Huffine, and Kevin Sheehan (eds.), Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, 1500-1800 (Stanford: 2009). Chapter 15: Daniela Bleichmar, ‘A Visible and Useful Empire: Visual Culture and Colonial Natural History in the Eighteenth-Century Spanish World, pp. 290-310

- Daniela Bleichmar, 'Painting as Exploration: Visualizing Nature in Eighteenth-Century Colonial Science,' Colonial Latin American Review 15: 1 (June, 2006), pp. 81-104

- Susan Deans-Smith, ‘Nature and Scientific Knowledge in the Spanish Empire Introduction’, Colonial Latin American Review 15, no. 1 (2006), pp. 29-38

- Paula Findlen, ‘Inventing Nature: Commerce, Art, and Science in the Early Modern Cabinet of Curiosities,’ in Pamela H. Smith and Paula Findlen (eds.), Merchants and Marvels: Commerce, Science, and Art in Early Modern Europe (2002), pp. 297-323

- Achim, Miruna (ed.), “Science in Translation: The Commerce of Facts and Artifacts in the Transatlantic Worlds,” Special Issue, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 8.2 (2007)

- Maria M. Portuondo, ‘On Early Modern Science in Spain’, in The Early Modern Hispanic World: Transnational and Interdisciplinary Approaches (Cambridge, 2017), pp. 193-219

- Maria M. Portuondo, “The Study of Nature, Philosophy and the Royal Library of San Lorenzo of the Escorial.” Renaissance Quarterly 63: 4 (2010), pp. 1106-1150

- Maria M. Portuondo, ‘Iberian Science: Reflections and Studies, in Special Issue: Iberian Science: Reflections and Studies, History of Science, 55: 2 (June, 2017)

- Paula de Vos, Natural History and the Pursuit of Empire in Eighteenth Century Spain, Eighteenth-Century Studies 40: 2 (Winter, 2007), pp.209-239