© Die Puppe (Ernst Lubitsch, 1919)

“She must have one complex mechanism”: Review of Die Puppe (The Doll, 1919)

Tom Double, King’s College London

“Vier lustige Akte aus einer Speilzeugschachtel”, the title card reads: “Four amusing acts from a toy chest”. Sure enough, in the film’s opening, a man takes the lid off a large wooden box, from which he removes and assembles a model of a hillside. Then he sets two little dolls inside a cabin and closes the lid. The film crossfades to a close-up, and the two dolls have become actors, the miniature models props and scenery. What may not be obvious is that the man in this prologue is the film’s director, Ernst Lubitsch. This is how the filmmaker sees himself: a little boy playing with toys.

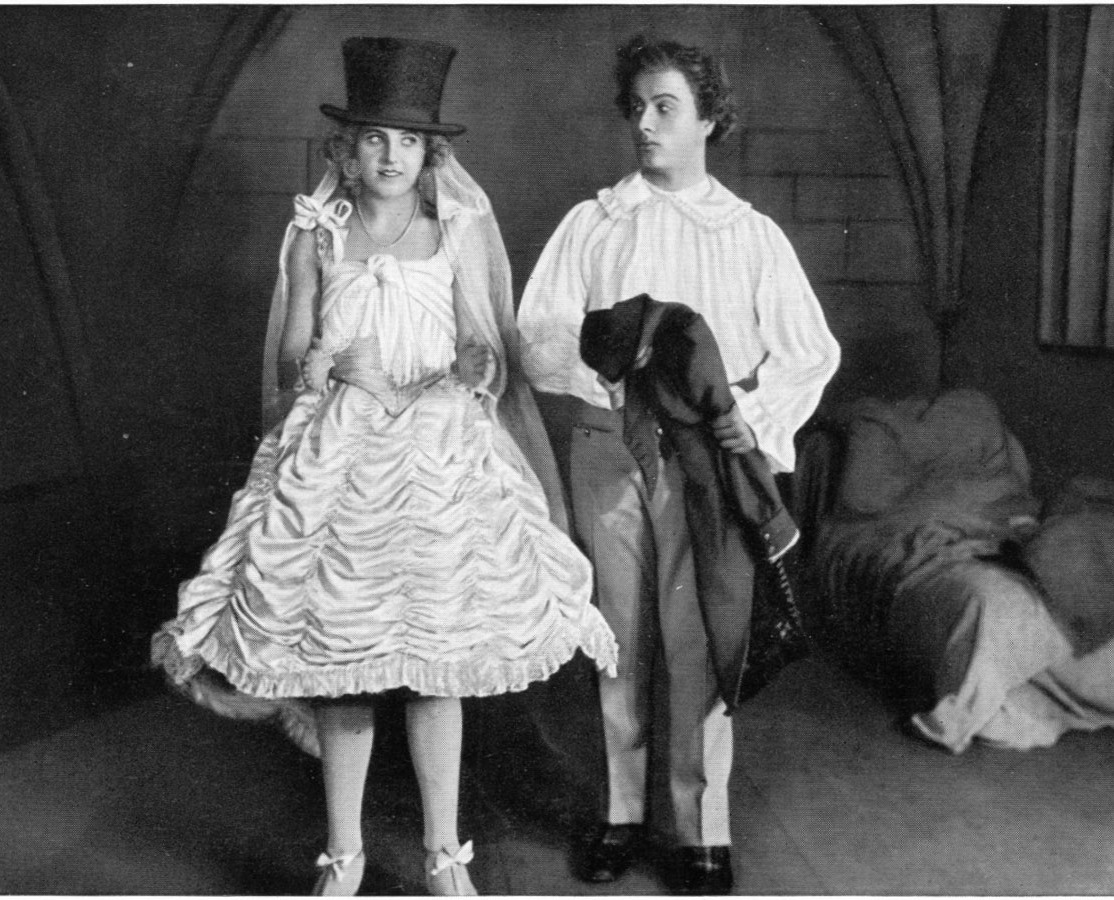

Thus begins Die Puppe (The Doll), a delightfully playful silent comedy and early offering from the Berliner director, who would later be famed across the world for his Hollywood screwball farces. The plot, derived from a story by absurdist author and fellow German E.T.A. Hoffmann, begins with Lancelot (Hermann Thimig), an immature young man prone to fits of crying. Lancelot is ordered to marry by the Baron von Chanterelle, being his nephew and only heir. Fearing the prospect, Lancelot flees to a local monastery, where a gaggle of fat friars are bemoaning their hunger. They agree to hide him, but soon catch wind of his 300,000 franc dowry. One of the men comes up with a plan: Lancelot can marry a lifelike mechanical doll created by the world-renowned dollmaker Hilarius (Victor Janson) and claim the reward for the church. When Lancelot arrives to pick up the doll, however, Hilarius’s precocious apprentice accidentally breaks its arm off, and the dollmaker’s daughter Ossi (the brilliant Ossi Oswalda), who just so happens to look exactly like it, is forced to take the doll’s place.

What follows is a contrived but multi-layered farce, in which Ossi must pretend to be an animatronic in front of Lancelot, but simultaneously pretend to be pretending to be a real girl in the company of his family. When introduced to the Baron, she jerks her hand back and forth violently in a faux-mechanical “handshake”. The Baron is baffled. “She’s from an old patrician family,” his nephew explains. “They’re all very formal.”

All the while, human desires cause her to act out of character – she steals draughts of alcohol and bites of her husband’s food when Lancelot looks away, returns his slaps on the wrist with blows to his face, and in several scenes displays an attraction to him which is very suggestively charged. In one scene, she becomes visibly excited upon entering the marital bedroom when Lancelot starts removing his suit, but is frustrated when he decides to use her as a clothes stand. Earlier, while travelling in a small coach compartment, she feigns mechanical failure in order to lean her head on his chest. At this point, Lubitsch cuts to the moon in the sky watching the pair with an animated cartoon face, which then winks at the camera.

Die Puppe is a stylised film, a modernist fairy tale, alive with a cheeky and often surprisingly obvious sexuality, set in a city which comes to life as it goes to bed. A shot of drunken revellers skipping through the moonlit street is followed by a man silhouetted in a window being undressed by another figure, as the lights inside the building switch off one-by-one. A more explicit shot of a man and a woman canoodling under a streetlamp cuts away to a shadow puppet of a cat meowing. Later on, when Lancelot finds out the truth about Ossi, after sensually feeling her arm and her neck to verify her fleshliness, the gag is repeated as their passionate embrace is interrupted by a cockerel crowing.

There is also a running joke about Hilarius’ young apprentice, ashamed of his responsibility in the farce, attempting to commit suicide by drinking paint (“It would be like you, to go drinking expensive paints!” his master cries upon stopping him) and throwing himself out of a window (where a cut reveals the room to be on the ground floor). But the film’s tone is playful, and the subversive humour is often defused by its absurdity. It’s as if Lubitsch himself is winking at us.

Oswalda is particularly great here. Her comic performance as the “doll” is the glue that holds the film together, as she reacts in frustration to the frankly ridiculous sequence of events that befall her. It’s a shame that she isn’t better remembered; almost exclusively playing characters called “Ossi” (including in multiple other Lubitsch films), and always fitting the same general type, a fiery New Woman, free to dish out as well as take it, Oswalda was known as ‘the German Mary Pickford’. A big compliment indeed, but a huge shadow to escape from under, and the comparison suggests an unfortunate lack of women in silent comedy. Fleeing the Nazi regime in the 1930s, she eventually died penniless in Prague, a sad legacy for such a talent, but common for stars of the silent cinema.

Evident here already is Lubitsch’s talent for comedy. His mastery of repetition and sharp wit manifests in the film’s script, as well as a playfulness and sexuality which would go on to push the boundaries of classical Hollywood style, here fostered by the comparatively socially liberal mores of the Weimar period. Die Puppe is a charming film, innocent but cheeky, absurd almost to the point of expressionism, and displaying a creativity which can still raise a laugh. A favourite moment is when Hilarius discovers his daughter has taken the doll’s place. “This is truly hair raising,” he says, and sure enough, in stop-motion, his hair stands up by itself and turns white; the very final shot of the film shows his hair becoming limp again as he sighs with relief. A silly gag, perhaps, but one that speaks for the film that came before it. Who could fail to be won over by its earnestness?