Palaeolithic Britain

Introduction to the Palaeolithic Age

The Palaeolithic Age is the name we give to the period which extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins (human-like creatures) around 3.3 million years ago, down to roughly around 11,650 years ago. Palaeolithic means 'Old Stone Age'.

Ancient Footprints

The earliest evidence of human occupation in Britain may date to around 900,000 years ago. These are in the form of footprints discovered in 2013 at Happisburgh on the Norfolk coast. Stone tools found nearby may be much later, but it is believed that the footprints may belong to the species Homo antecessor. As the evolutionary tree on the Human Evolution page reveals, exact relationships between the different historic species of Homo remains unclear, though some see Homo antecessor as a descendent of the African Homo erectus, and which in Europe gave rise to Homo heidelbergensis, the next species to appear in Britain.

These footprints are not only the first evidence of humans in Britain, but are the oldest human footprints found outside of Africa.

At this time, Southern and Eastern Britain were linked to continental Europe by a wide land bridge that we now call Doggerland (see section on Neanderthals below for map), allowing humans to move freely. These early peoples made flint tools (such as hand axes - see figure below) of a kind known as Acheulean, and hunted the large native mammals of the period. One hypothesis is that they drove elephants, rhinoceroses and hippopotamuses over the tops of cliffs or into bogs to more easily kill them. Evidence for prehistoric elephants in Warwickshire exists, as will be seen below.

Boxgrove Man

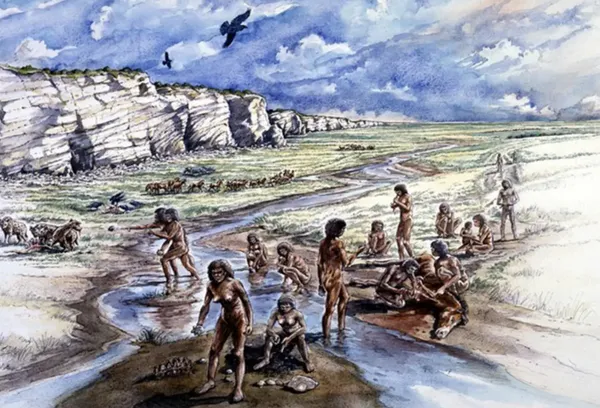

The oldest human fossils (as opposed to just footprints) in Britain date to around 500,000 years ago, are of a species known as Homo heidelbergensis. These were found at Boxgrove in Sussex. The inhabitants of the region at this time were bands of hunter-gatherers who roamed Northern Europe following herds of animals, or who supported themselves by fishing. Boxgrove Man, as he is sometimes called, lived in Britain during a period of relative climatic stability.

UK's oldest stone tools from near Coventry

Five andesite (a volcanic rock) handaxes dating from this period have been found at Waverley Wood near Coventry. Dating from 500,000 years ago - around the same time as the human remains from Boxgrove - these are the oldest stone tools yet found in the UK. The stone tools are thought to represent a temporary hunting camp made by a small group of early humans. Waverley Farm Pit site is comparable with the other sites of early humans at Boxgrove (W Sussex), High Lodge (Suffolk), and Kents Cavern (Devon). Waverley Wood lies near Bubbenhall.

The Waverley Wood handaxes were chosen by the BBC for its Radio 4 'A History of the World' programmes. As the BBC website tells us, the handaxes were found with the fossilised remains of straight-tusked elephants, prehistoric horse and water voles, and their age and their significance for the history of early humans in the Midlands was soon recognised. The andesite rock they are made of is likely to come from the Lake District and may have been deliberately chosen and brought into this area for its colour and appearance, which is very different to the local quartzite. This hints at possible connections between groups of people in Britain at that time, and of the movement and trade between them.

A Lower Palaeolithic Handaxe from Waverley Wood, Warwickshire.

The presence of these axes with the animal remains tell us that groups of an early form of human, Homo heidelbergensis were moving around this area of the Midlands half a million years ago, in an Inter-glacial period - i.e. in a relatively warm period between two colder snaps. The variety of animal remains gives us some idea about the climate of the time, which was very different to that of today.

Evidence for prehistoric elephants was been found near Coventry during quarrying at Ryton Pools, and some metal sculptures (left) have been created and installed to help bring to life the geological history of the area at the pools. Pieces of neck bone, tooth and tusk of the Straight-tusked elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus (see picture below), were all found in the local sand quarries, and these creatures would have roamed the area around half a million years ago. You can find out more about prehistoric Ryton from this leaflet created by Warwickshire Geological Conservation Group. Perhaps think about visiting Ryton Pools and exploring the area yourself.

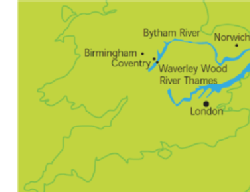

The elephants would have been found enjoying an almost tropical climate along the banks of the ancient Bytham River, the largest river in Britain at the time and which ran from near present day Stratford-Upon-Avon to the Norfolk coast. You can see the course of the Bytham River in the map (right).

So a visit to the Coventry of half a million years ago would be to a pleasant warm wilderness, inhabited by straight-tusked elephants beside the Bytham river, with bands of Homo heidelbergensis living in small hunter-gatherer groups, no doubt hunting these straight-tusked elephants and other prehistoric fauna.

Below is a reconstruction of the straight-tusked elephants that would have wandered beside the Bytham River on the outskirts of modern Coventry (image: Wikimedia Commons).

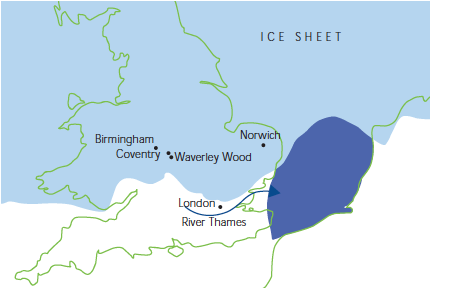

After this period of stability and warmth, Britain entered an ice age, the so-called Anglian Stage (around 450,000 years ago), which we believe was severe enough to have driven humans out of Britain altogether. The light blue area on the map to the left shows the extent of an ice sheet that covered the Midlands completely. The region does not appear to have been occupied again until the ice receded during the so-called Hoxnian Stage (see chart on this page). This warmer period lasted from around 424,000 until 374,000 years ago and is associated with evidence of humans at Swanscombe in Kent. What species Swanscombe Man is (the skull actually seems to be female), we do not know - possibly either an archaic human species or a Neanderthal (Homo neadnerthalensis).

After this period of stability and warmth, Britain entered an ice age, the so-called Anglian Stage (around 450,000 years ago), which we believe was severe enough to have driven humans out of Britain altogether. The light blue area on the map to the left shows the extent of an ice sheet that covered the Midlands completely. The region does not appear to have been occupied again until the ice receded during the so-called Hoxnian Stage (see chart on this page). This warmer period lasted from around 424,000 until 374,000 years ago and is associated with evidence of humans at Swanscombe in Kent. What species Swanscombe Man is (the skull actually seems to be female), we do not know - possibly either an archaic human species or a Neanderthal (Homo neadnerthalensis).

Neanderthals and Lakes

The scouring of the glaciers had a huge effect on the geography of the Midlands. The Bytham river disappeared, and instead a huge lake - Lake Harrison - formed covering much of the Midlands around Warwick, Birmingham and Leicester. Lake Harrison was formed when ice from Wales and the north blocked the drainage of water from the Midlands, which when trapped formed a lake between the ice front and the Cotswolds. Finally the lake made two overflow courses:

- Southeast across the Fenny Compton Gap through the Cherwell valley into the Thames. This course has now been abandoned.

- Southwest in a course which is now followed by the River Avon, which flows into the river Severn.

As we said above, fossils of very early Neanderthals dating to around 400,000 years ago may have been found at Swanscombe in Kent (if these are indeed Neanderthal remains). But fossils which have clearly been identified as Homo Neanderthelensis, dating from about 225,000 years ago, have been found at Pontnewydd in Wales. After these, there is no record of humans in Britain between 180,000 and 60,000 years ago, after which the Neanderthals returned once again to Britain.

There was limited Neanderthal occupation of Britain between about 60,000 and 42,000 years ago. Britain had its own unique variety of late Neanderthal handaxe, called the bout-coupé. The development of a distinct British type seen nowhere else seems to speak against the idea that the Neanderthals migrated seasonally into Britain, perhaps following migrating herds. Instead, mostly staying put, it seems that the British Neanderthals developed their own technology. Their main site of occupation is thought to have been in the now submerged area of Doggerland (now lying under the North Sea - see below), with small summer migrations to Britain in warmer periods. La Cotte de St Brelade in Jersey in the Channel Islands is the only site in the British Isles to have produced late Neanderthal fossils.

Doggerland

At the end of the last ice age, Britain formed the northwest corner of an icy continent. The warming climate exposed a vast continental shelf for humans to inhabit, and further warming and rising seas gradually flooded low-lying lands. Some 8,200 years ago, a catastrophic release of water from a North American glacial lake and a tsunami from a submarine landslide off Norway inundated whatever remained of Doggerland. You can find out more about the current thinking about Doggerland in an excellent National Geographic article here.

Above: Map showing the changing extent of Doggerland from 16,000 BCE down to the present day (source: Doggerland - The Europe That Was | National Geographic Society)

Homo sapiens arrive in Britain

By 40,000 years ago the Neanderthals had become extinct and modern humans had reached Britain. But even these occupations were brief and intermittent due to a climate which swung between low temperatures with a tundra habitat and severe ice ages which made Britain uninhabitable for long periods. The last of these, the Younger Dryas, ended around 11,700 years ago, and since then Britain has been continuously occupied. Britain and Ireland were then joined to the Continent, but rising sea levels cut the land bridge between Britain and Ireland by around 11,000 years ago. The large plain between Britain and Continental Europe, known as Doggerland (see map above), persisted much longer, probably until around 5600 BC.

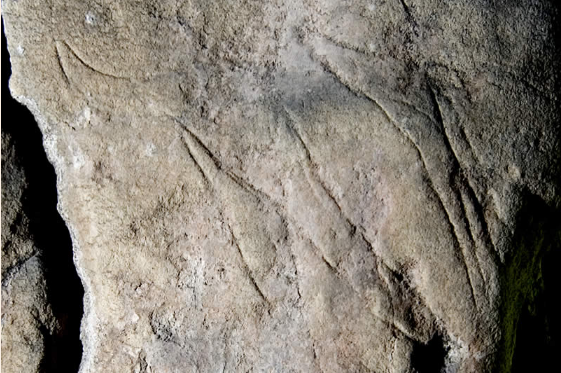

The Robin Hood Cave Horse is a fragment of horse rib engraved with a horse's head, discovered in 1876, in the Robin Hood Cave in Creswell Crags

Food species were predominately horse (Equus ferus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus), but mammals including hares, mammoth, rhino and hyena were also hunted. Some of these animals were depicted in early art such as the Robin Hood Cave Horse (above) engraved on a rib. Examples of cave art from this period are found at Creswell Crags (below) and at Mendip caves.

The images inscribed in Church Hole at Cresswell Crags (above) include images of bison, reindeer and birds, as well as some abstract symbols which may have had religious meaning.