2. Reflective Practice: foundations and concepts

Where do these ideas come from?

It’s usually not a bad idea to start with a definition or two, so here are three to get us started!

The Oxford English Dictionary calls reflection an action of "thinking carefully or deeply about a particular subject", by considering your "past life and experiences". They also give a philosophical and psychological definition, that reflection is the mind observing and examining "its own experiences and emotions; intelligent self-awareness, introspection." So, it’s about examining a subject, which could be your own experiences, and it’s about taking your life and experiences into account when you draw conclusions.

At this point, it’s worth repeating our own definition of Self-reflection as a skill:

The ability to perceive and evaluate your cognitive, emotional, and behavioural processes, and set actions for development.

Our definition has two stages in it. First, you examine the subject and the experience, which includes those “cognitive, emotional, and behavioural processes”. Then, you use what you’ve learned from that to plan what to do with your experiences and how to build on them.

Like the second dictionary definition, reflecting means drawing conclusions, and drawing conclusions means looking forward and applying what you have learned. Even though reflection and reflective practice might be understood differently by people in different situations, this process of thinking and learning brings all of our different understandings and approaches together. This idea has some of its modern origins in the work of philosopher John Dewey.

John Dewey and Reflective Thinking

Active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends, constitute reflective thought.

John Dewey, How We Think (1910)

John Dewey was a philosopher and psychologist who became very interested in education and socialisation. He was an early advocate for reflection as a form of thinking which stems from experience. He saw it as a way of involving people in their own learning by moving away from routine, tradition, and conformity towards cooperation and problem solving by combining thinking and doing (Finlay, 2008; Smith, 2011).

There’s a great biography of Dewey here by the National Endowment for the Humanities if you would like to find out more.

David A. Kolb and Experiential Learning Theory

David A. Kolb and Experiential Learning Theory

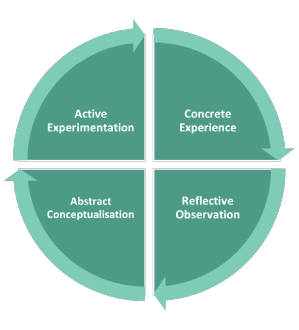

David A. Kolb is an educational theorist and the founder of Experience Based Learning Systems (EBLS), a research and development organisation “devoted to advancement of the theory and practice of experiential learning”. He began to develop his interests in experiential learning from the early 1970s, beginning with a four-stage Experiential Learning Model:

Concrete Experience - getting actively involved

Reflective Observation – reflecting on experiences and actions

Abstract Conceptualisation - analysing and conceptualising

Active Experimentation - problem solving and decision making

It is intended to be repeated and to become a continuous process of learning. It can be presented as a cyclical process, as you can see in the diagram, and it can be applied to a wide range of experiences, so it’s useful as a guide to reflecting on activities. It has proven to be very influential on subsequent theories around reflective practice, including Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle which we will focus on in the next section.

Donald Schön: The Reflective Practitioner and Reflection-in-Action

Trained as a philosopher, Donald Schön developed his ideas around reflective practice through a fascination with technological change and the adaptation of social systems, and with the ways professionals and practitioners make sense of – and make improvements in – the world in which they operate. He drew on his direct experience as a product design consultant for consultancy Arthur D. Little and began to develop his analysis of the relationship between ideas and practice as professor of Urban Studies and Education at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1972. He was also influenced by several collaborations and conversations with other scholars on fields including cognitive development, organisational development, and cybernetics, as well as his musicianship and love of music (Ramage, 2017).

Donald Schön contributed a number of important and innovative ideas to the fields of design, professional education, and organisational learning, but one of the most prominent, and the one we are focusing on here, is that of Reflection-in-Action.

Much reflection-in-action hinges on the experience of surprise. When intuitive, spontaneous performance yields nothing more than the results expected for it, then we tend not to think about it. But when intuitive performance leads to surprises, pleasing and promising or unwanted, we may respond by reflecting-in-action.

Donald A. Schön,The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (1991, 2016).

Schön describes Reflection-in-Action as the practice that includes “thinking on your feet” and “learning by doing”. It encompasses improvisation, adaptation, “learning to adjust” and repeat successful actions. He notes examples from performance, of both sportspeople (baseball pitchers who adapt to the batter and “get in their groove”) and musicians (jazz players who improvise together), "thinking what they are doing and, in the process, evolving their way of doing it", generally without words and, maybe, not always consciously.

Reflection-in-Action is based on 'knowing-in-action', which is about that application of skills that can be more than our understanding of the rules or techniques we deliberately learned. As Schön says, " in much of the spontaneous behaviour of skilful practice we reveal a kind of knowing which does not stem from a prior intellectual operation."

It is also often described alongside Reflection on Action, or consciously and deliberately after the experience, which is the kind of measured exercise most of the other models and techniques here are geared towards. However, if you are aware of Reflection-in-Action when you reflect on action, you will be able to identify and consider those seemingly automatic or intuitive processes by which you adapted and improved in the moment.

Reflection-in-Action

- Taking notes as you work and using them to make decisions

- Asking targetted questions to get informal feedback and make immediate adjustments

- Repeating an action with incremental adjustments until you hit on the most effective or efficient technique

Reflection on Action

- Reviewing a performance afterwards, recalling and analysing adaptations

- Discussing your experience and actions with someone else who was there and comparing your perspectives and approaches

- Answering questions to reflect on a Warwick Award activity, considering which Core Skills you practised and when