History News

Universities and the legacies of slavery

White ‘Slaves’: Christopher Codrington and His Disputes with Colonial Elites

Recently there has been considerable debate about the legacy of Christopher Codrington, and his bequests to Oxford University’s All Souls College. As a dominant plantation-owner in the British Caribbean, Codrington’s wealth was built on the labour and lives of enslaved people, and the plantation profits he left for All Souls continue to cause public controversy. Under the pressure of activists and campaigners, All Souls has decided to change the name of Codrington Library, but not to move Codrington’s statue which stands in the centre of the library [Oxford University’s All Souls College drops Christopher Codrington’s name from its library—but refuses to remove slave owner’s statue | Anny Shaw | The Art Newspaper]. Whilst attention has very rightly focused on his slave-holding, we should also not forget his involvement in bitter internecine conflict with local elites and the related language of slavery among the white community.

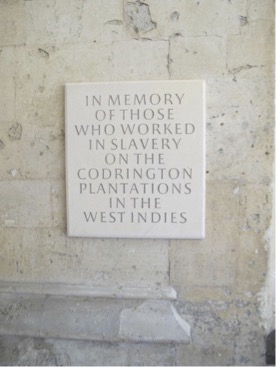

The memorial plaque at the entrance to the All Souls library [The Codrington Legacy | All Souls College]

Codrington was born in the parish of St. John’s in Barbados, in 1668. After spending twelve years in his birthplace, he was, like many other colonists, sent to a private school in England and enrolled at the University of Oxford when he was seventeen. In 1692, when King William decided to attack the French in the West Indies, Codrington sailed as a volunteer with Colonel Goodwyn, and one year later when the King went to Flanders on a campaign, he was made the Captain of the First Regiment of Foot Guards.[1] After that, Codrington distinguished himself at the siege of Namur, and was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and captain of the guards in August of 1695.[2] His good education and military skills won him the favour of the king, and after the death of his father, Codrington was appointed as the next governor of the Leeward Islands. Although Codrington’s investment in slaves is criticised by people nowadays, what he did was common for planters like him in the seventeenth century. The real points of controversy from his perspective were his bitter disputes with other figures from the white colonial elite in the political and economic spheres.

During his career as governor, Codrington was embroiled in land disputes with local inhabitants, and was attacked for his involvement in illegal trade. In the late seventeenth century, repeated conflicts between Britain and France in the Caribbean area led to islands passing back and forth between the two empires. This mutability led to a lack of clarity about who was entitled to ownership of plantations, especially when some planters took such opportunities to seize large amounts of land. In 1701, Codrington was attacked by other planters in both Nevis and St Kitts for encouraging his agents to seize plantations illegally and interrupting judicial proceedings. This unsurprisingly resulted in disputes among the colonial land owners. His enemies included William Mead, the commissioner of customs and a councillor of Nevis and St Kitts, and James Norton, the lieutenant governor of St Kitts who he had removed. For Codrington himself, however, this was not about lands but about factional politics in the colony. According to Codrington, Mead had used factions to control Nevis and to serve his own interests. Both the chief judge, Charles Pym, and the president, William Burt, were not only his tools, but his ‘slaves’.[3] The opposition elites presented a petition before the House of Commons, and the case was heard before the House in 1702. Nevertheless, due to the hard work of his agents and friends at home, Codrington was exonerated.[4]

For the mother country at that time, Codrington was an ideal governor, in particular when the colony was under the shadow of war. He was well-educated and loyal to the crown. But unlike many other Caribbean governors, Codrington was wealthy enough to not have to rely on financial inducements from the assembly, which meant he was less likely to be manipulated by it. Besides, his military talent made him a good commander for the colony. However, one year after the case of land disputes, Codrington’s reputation as a good commander was damaged by his inability to co-ordinate the army and the failure of an attack on French-held Guadeloupe.[5] His application for leave was agreed to by the mother country, and although he tried to obtain reinstatement as governor over the next few years, he never resumed the office of governor.

When his successor Daniel Parke took the office, Codrington was complained about for accumulating wealth through clandestine trade, in violation of the acts of trade. In a letter to the Board of Trade, Parke noted that a large number of planters, Codrington included, were involving in smuggling. To protect the illegal trade, Codrington had appointed his agent Edward Perry, who had been raised by his father, as collector of customs in Antigua. As Parke averred, it was an irregular appointment, because Perry was a trader himself, and had ‘near 3,000l. cargo last year from England, wch he sells by retail’.[6] Meanwhile, Edward Perry’s brother, John, served as the provost marshal of the colony. The two brothers were the assistants of Codrington in his smuggling activities with the French and Dutch. Yet these accusations did not result in much danger or damage to Codrington, for due to the so called ‘salutary neglect’ policy of the metropole, illegal trade in the colonies was a very grey area in the early eighteenth century. Indeed, Codrington was left to foment unrest on Antigua, leading to Parke’s murder in 1710 by an enraged mob. Codrington was never brought to justice for his part in it.

When he died in 1710, Codrington left £6000 to All Souls to pay for the building of a new library, with a further gift of his own collection and a further £4000 to be laid out on books.[7] This was certainly the profit of slavery but it was almost certainly also the result of smuggling and of using his considerable economic and political power to his own advantage. That manipulation and abuse of office caused considerable tensions within the white planter elite, some of whom ironically used the term ‘slave’ to describe their own subordinated status and complained about the arbitrary behaviour of the governors. For example, an inhabitant of Bermuda complained in 1689 that people were under ‘great slavery’ because of the governor’s avarice, which had not only destroyed trade but lost the customs in England £3000 per annum.[8] Likewise, the Committee of Safety of New York in a report of the same year talked of ‘the oppression and slavery imposed by the late Governor and Council’.[9] And when the inhabitants of the Leeward Islands levelled charges against Governor Parke, they claimed he designed to make terms for himself only, and surrender the inhabitants to slavery. In this context, slavery was described as an evil tool of arbitrary administration. The similar usage also appeared in the works of early modern writers. When Edward Long later examined the constitutional disputes in Jamaica, he claimed that there was ‘one set of persons uniting its efforts to enslave mankind; and another set to oppose such attempts and vindicate the cause of freedom’.[10]

In this sense, there were two languages of slavery in the colonial history that can be found in Codrington’s story: the one applied to Africans and the other to colonial governance issues and conflict within the white community. On the one hand the planter class insisted on their own liberty while on the other hand they denied liberty to the enslaved people. The first language of slavery had been studied by many researchers, but the second one, which linked with colonial political culture and practice, still needs further research.

Christopher Codrington (1668–1710) © All Souls College, Oxford

References:

[1] George C. Simmons, ‘Towards a Biography of Christopher Codrington the Younger’, Caribbean Studies, 12 (1972), p. 38.

[2] Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Codrington, Christopher’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [consulted at https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/5795].

[3] Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Vol 19, 1701, pp. 318-30, Governor Codrington to the Council of Trade and Plantations, 30 June 1701 [consulted at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol19/pp318-330].

[4] Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Codrington, Christopher’.

[5] Ibid.

[6] CSPC, Vol 23, 1706–1708, pp. 680-701, Governor Parke to the Council of Trade and Plantations, 8 March 1708 [consulted at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol23/pp680-701].

[7] Scott Mandelbrote, ‘Codrington, Christopher’.

[8] CSPC, Vol 13, 1689–1692, Henry Hordesnell to the Prince of Orange, 12 Apr. 1689 [consulted at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol13/pp20-33].

[9] Ibid, Abstract of the proceedings of the Committee of Safety of New York from 27th June to 15 August, 15 Aug. 1689 [consulted at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol13/pp113-127].

[10] Edward Long, The History of Jamaica, or, A General Survey of the Ancient and Modern State of that Island, vol Ⅰ (London: 1774), p. 25.

Qianwen Qing, PhD student, Department of History, University of Warwick