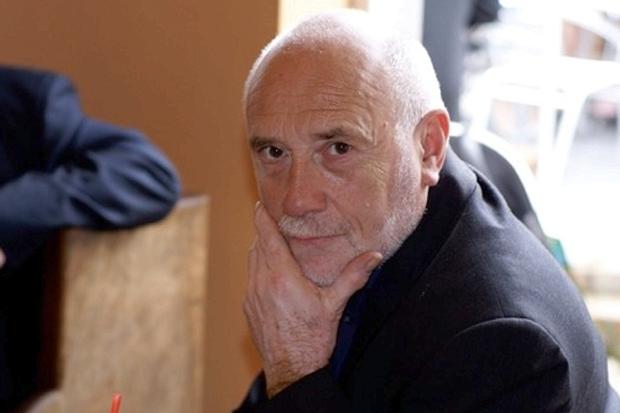

Emeritus Reader Roger Magraw: Obituary

From early on in his career, my former partner, Roger Magraw, who has died aged 71, was a committed and fearless historian. Standing before several giants of the Oxford history faculty, including Hugh Trevor-Roper, in the viva for his first-class degree, Rog was asked what he thought of Edmund Burke. He replied that, as a political philosopher, he lived up to his surname.

His professional life, from 1968, centred on the history department at the University of Warwick, where, partly under the influence of EP Thompson, a great collection of social historians was gathering. Rog was at its heart, not only intellectually but socially.

His writing was marked by a passion for his subject and, like his shambolic dress sense, was not in the least beholden to fashion. His book France 1815-1914: The Bourgeois Century remains the standard text for students of 19th-century France and demonstrated his interest in the lives of working people, rather than of those with power and privilege.

He was awarded the Ordre des Palmes Académiques from the French government in recognition of his work.

Rog was born in Birmingham. His mother, Nellie (nee Plant) worked for the Ministry of Labour in the city; his father, William, was in the RAF. After studying at Worcester College, Oxford, Rog joined the history department at Leeds University for a year, then went to Warwick, retiring as senior lecturer in 2006.

While politically Rog was exacting, in his personal life he was a beacon of kindliness, a support to his friends and colleagues, and to his students whatever their political views.

On retirement, in Earlsdon, Coventry, he continued his research in the university library. Before his death he was working on a book on jazz and popular culture in France from the 1920s to the 60s.

He is survived by his daughter, Nathalie, from his marriage to Liz (nee Marot), from whom he was separated, by his brother, Stephen, my daughter, Marianne, and grandson, Alfie.

Susan Hall, published in The Guardian, 10th December 2014

Roger joined the Department in 1968; an auspicious year given his political commitment and the focus of his research. He retired as a senior lecturer in 2006 and was awarded the status of emeritus Reader and D.Litt by the university in 2007. Roger was one of the leading scholars of nineteenth-century French social history and received the Ordre des Palmes Académiques from the French government in recognition of his work. His major two volume monograph on the history of the French working class showed the deepest mastery of primary and secondary sources and an unapologetic sympathy for his subjects. His most popular book, France 1815-1914: The Bourgeois century remains the standard text for students of nineteenth-century France. But his published oeuvre ranged widely and includes an eclectic collection of articles and essays reflecting his interests in labour history, historiography, consumerism and musicology. The piece he was working on before his untimely death focused on one of his major loves: jazz. He argued that the idea of ‘Jazz as Resistance’ in Vichy France was largely a myth, and that the truth was more mixed and mundane.

Roger was a much loved teacher and colleague. His brilliant lectures, accompanied by detailed, hand-written crib sheets inspired many. His past students have written in with their own memories including the news reader, royal correspondent and past French and History student, Jennie Bond who wrote, ‘Roger was a great lecturer... at least I remember liking him… but we were very naughty in ’68-’72 and nobody remembers much!’

Roger would often be found roaming the corridors of the Humanities Building at all times of the day and night. His chaotic office was littered with newspaper cuttings, photocopies of articles, gingernuts and cups of strong coffee. He liked nothing better than to debate key political issues of the day with anyone passing. As admissions tutor, he did much to improve the social profile of the intake of undergraduate students. In these days of widening participation, his strategy would have been regarded as a tremendous asset. He was always willing to listen and to offer advice. His Luddite tendencies were legendary. He eschewed email which meant you had to speak to him to exchange information; a refreshing change when academics and students rarely talk face-to-face. He never learned to drive and took his first flight when in his fifties. His last article was handwritten and delivered to one of the secretaries to type up.

Roger was an expert on so many topics: cricket, football, music, politics, historical theory and methods. He was a generous, principled and much-loved colleague. He will be sorely missed.

Dr Sarah Richardson, Warwick University History Department

From early on in his career Roger Magraw showed himself to be an historian of the greatest ability, commitment, passion and fearlessness. On parade before several greats of the Oxford History faculty, including Sir Hugh Trevor-Roper, in his viva on the occasion of his receiving a spectacular first class degree, Rog was asked what he thought of Burke. He replied that, as a political philosopher, he lived up to his name. A unique, courageous and determined career had been launched. It continued with a brief sojourn in the History Department at Leeds, notable for two things. Rog was loaded with a spectacular number of first year lectures at limited notice – a regular fate of junior lecturers at the time compared to today’s 40% teaching load reductions – and, secondly, for Leeds persistence, despite all Rog’s efforts to dissuade them, in continuing to pay him for a significant time after he had left. This was possibly the only occasion on which one of Rog’s multitude of entanglements with the existential absurdities of the great modern bureaucracies that dominated his and our lives – universities, banks, public utilities – came out in his favour. There was little Rog enjoyed more than regaling colleagues with his encounters with one or the other. His disdain for the modern, which left his ‘workstation’ unused in the corner of his office, (did anyone ever get an e-mail from Rog?), not only extended to bureaucracies but also to cars, which he never learned to drive, and even to the bicycle, which he never learned to ride. This left him a frustrated, amused and outraged victim of the declining British public transport system of the neoliberal years. Epic tales of trying to cover the modest 25 miles or so from Leicester to Coventry on a Sunday evening, after visiting his beloved daughter, took on the scale of episodes from The Odyssey. The frequent, phlegmatic response of the platform staff at Nuneaton that the connection to Coventry always left about a minute before the train from Leicester arrived became the stuff of legend. In his younger years Rog had travelled in an ancient motor vehicle of some kind to Istanbul, a trip which threatened him with an enforced beard trim at the borders of the Colonels’ Greece. He was no hippy and the journey beyond Istanbul to Afghanistan, unimaginably undertaken by so many at that time, did not interest him. His own lack of driving skills also exposed him to a winter pillion journey on a motorcycle from Coventry to attend a jazz performance in Bristol.

From 1968 Rog’s professional life centred on the History Department at Warwick where, partly under the influence of E.P.Thompson, a great collection of social historians was gathering. Rog was at the centre, not only intellectually but socially. When the department moved to a new building – a cross between Slade prison and a Foucauldian panopticon – Rog’s office became the human heart of the corridor. The smell of smoke and the buzz of lively conversation drifted incessantly from it. Colleagues foregathered there to talk, plot, theorise and denounce and to drink unhealthy quantities of instant coffee, much of which appeared to have soaked into the carpet, the chairs and not a few of Rog’s lecture notes left lying unprotected on his desk, not infrequently next to an uneaten piece of pork pie or a forgotten packet of biscuits. Had the world been governed from that office it would certainly have been a much better place today!

Rog’s attachment to social history came from a wider commitment to the exploited and downtrodden and a corresponding loathing of the hypocritical lords of the earth in whatever pretentious guise they showed themselves. His immense knowledge, respect and reverence for the workers and peasants of nineteenth-century France was at the heart of his teaching and his formidable range of publications. His major works, on French left-wing theory and on the French working class showed the deepest mastery of primary and secondary sources and an unapologetic sympathy for his subjects. His most popular work, France 1815-1914: The Bourgeois century was drafted in few months in a room in a friend’s home in which he took refuge in the face of relationship turmoil of which he had more than his fair share. The intense inspiration was fuelled by whisky shots and the occasional foray for food and would strike at any time of day or night. The speed of production and the quality and quantity of the output had to be seen to be believed. Like most of his written work, not to mention his brilliant, overloaded lectures, Rog produced twice as much material than required. He appeared to spend more time, effort and anxiety cutting his drafts down to size than he did in producing them in the first place. Even his magisterial two-volume and over 600 page history of the French working class in the nineteenth century was drafted some 100% over length.

His writing, like his life, was marked by commitment, passion for his subject matter and, like his shambolic dress sense, was not in the least beholden to fashion of any kind. For all that he admired Marx, especially 18th Brumaire which he used as a disinfectant spray to disperse the trendy platitudes of postmodernism in the ever more reactionary decades after 1980, he could not be categorised as a Marxist. His writings were much more complex than that. They showed consciousness, even mastery, of theory but seldom followed any specific prescriptions. But Rog was no pure empiricist either. Class struggle featured prominently in his work and in his life, but he knew there were no universal theories that measured up to all the complexities of day-to-day reality.

While politically Rog was certainly an enragé, in his personal life he was a beacon of kindliness, support for his students no matter what their own politics were (though he was disappointed at what he saw as their growing political and social-analytical illiteracy) and a prop to his friends and colleagues when they needed him. His sudden departure has left a hole in many lives. The thought that he is no longer there to dispense radical common sense in the face of our multiple political, social and economic crises is hard to bear. A voice of immense value has been silenced.

Professor Chris Read, Warwick University History Department