History of sleep

Curators

- Liv Chester (History)

- Becca Aspden (History)

- Christopher Bird (History)

History of sleep

Sleep, a universal human delight, has had a rich history despite most of it being spent asleep. This cabinet briefly examines and explains some of its historical components.

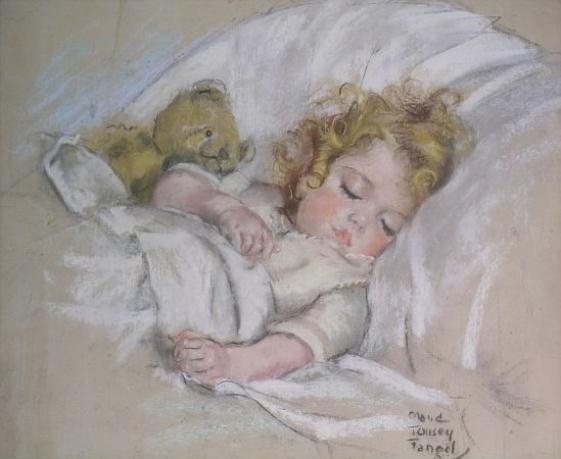

Sleeping child [1920s] by Maud Tousley Fangel

Children's sleep

![The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of/Dreams [1858] by John Anster Fitzgerald](dreams_painting.webp)

The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of/Dreams [1858] by John Anster Fitzgerald

Dreams

Ever since we have slept, we have sought to decipher the hidden meanings and messages behind these dreams to better understand ourselves. Dream interpretations have been a part of human history ever since we have been curious with various theories and cultural practices being used to interpret the dreams we have. With the rise of psychoanalysis in 1896, psychiatrists such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung started to incorporate dream interpretation within the field, intertwining it with hypnotism. This has been fictionalised and reflected upon by writers such as Pat Barker and her book Regeneration which is about Craiglockhart and the experiences of psychiatrist W.H.R. Rivers. She specifically explores the significance of these practices on soldiers who fought during World War One. In the current day, dream interpretation practices are still frequently used. Many people either look to dream books or guides such as The Universal Dream Book to make sense of recurring images within dreams, while others look to the psychological significance of their dreams with the help of therapists. Ultimately, the history of sleep has shown that dream interpretation a very subjective practice, with many either taking a scientific or spiritual approach. But both approaches aim to uncover the deeper meanings behind human emotions and reactions through the art of sleep.

The history of Insomnia

Insomnia has changed throughout history as our sleep patterns have changed. Before the 19th century when people would sleep in two blocks middle of the night (MOTN) insomnia wasn’t perceived as an issue. One of the first references to insomnia was in Thomas Elyot’s ‘Glossary Bibliotheca Eliotae’ in 1542 but the word wasn’t used readily until the 19th century.

As people dropped their second sleep MOTN insomnia became an issue many people reported whereas previously it wasn’t noted. So, MOTN insomnia could be a remnant of our previous sleep patterns but now it is a medical issue and viewed as something we need to treat.

Sleep remedies throughout history

There have been many historical remedies for insomnia. It was advised during the late 16th century that music or soothing sounds, such as the swaying of trees, could help someone with falling asleep. As treatment for sleeplessness was focused on a calm body and mind.

It was also viewed that sleep was caused by diminished circulation to the brain during the 19th century. So, remedies focused on soothing the nervous system and reducing activity of the heart, to reduce blood flow to the brain. This included using potassium bromide which was believed to assert an anaemic reaction.

During the 19th century Beechams pills were advertised as a cure for insomnia, and these are presently used as a cold remedy.

Nowadays, many over-the-counter remedies are usually antihistamines. There are also melatonin tablets which can be given by prescription but also can be bought online from unregulated sites as supplements.

Polyphasic sleep

Bibliography

- Ekirch, Roger A. “Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles.” The American Historical Review 106.2 (2001): 343–386.

- Lisa Anne Matricciani, Tim S. Olds, Sarah Blunden, Gabrielle Rigney, Marie T. Williams. “Never Enough Sleep: A Brief History of Sleep Recommendations for Children.” Pediatrics (2012): 548–556.

- Oskar G. Jenni, Bonnie B. O'Connor. “Children's Sleep: An Interplay Between Culture and Biology.” Pediatrics (2005): 204–216.

- Stearns, Peter N, Perrin Rowland and Lori Giarnella. “Children's Sleep: Sketching Historical Change.” Journal of Social History 30 (1996): 345-366.

- Williams, Simon J. “Sleep and health: sociological reflections on the dormant society.” Health 6 (2002): 173–200.

- Wolf-Meyer, Matthiew. “The Nature of Sleep.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 53 (2011): 945–970.

-

Ekirch, A. Roger. 2015. ‘The modernization of western sleep: or, does insomnia have a history?', Past&Present 226 (2015)

-

MacLehose, William. 2020. ‘Historicising Stress: Anguish and Insomnia in the Middle Ages’, Interface Focus, 10.3 (Royal Society): 20190094–94.

-

Neubauer, David N. 2007. ‘The Evolution and Development of Insomnia Pharmacotherapies’, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 3.5 Suppl: S11 <https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1978321/> [accessed 16 February 2025]

-

Schulz, Hartmut, and Piero Salzarulo. 2016. ‘The Development of Sleep Medicine: A Historical Sketch’, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12.07 (American Academy of Sleep Medicine): 1041–52.

From the exhibit