Francis Skidmore (1817-1896)- Long Biography

Francis Skidmore (1817-1896) became a leading figure in the Gothic Revival movement, which drew inspiration from medieval design. His expertise made him perhaps the best-known craftsman in the country. At the height of his popularity his work could be found in twenty-four cathedrals, in 300 or more parish churches, fifteen universities, and public buildings like the Royal Exchange in Liverpool and St Pancras station in London. In 1864 he produced metalwork for the Albert Monument in Kensington Gardens, commissioned by Queen Victoria. Skidmore’s decline in fortunes was just as rapid as his rise to success. Brought about both by the declining popularity of the Gothic Revival style, and his own poor business acumen, he lost control of his company in 1872, and died in ‘rather humble circumstances’ in 1896. Today his work is nevertheless celebrated and widely exhibited.

Rise to success

Born in Birmingham in 1817, Skidmore grew up in Coventry. Perhaps influencing the ecclesiastical basis of much of his work, he was raised in a strongly Anglican environment. His father served as a churchwarden for Holy Trinity Church in the centre of Coventry, and the church was to commission his first independent project, a pair of chalices. In 1853 he married Emma, ‘a lady of very similar tastes to his own’ in the same church. They had seven children, though only four were to survive to adulthood.

Apprenticed to his father’s jewellery making business, Skidmore learnt the traditional skills of engraving, casting, enamelling, and mounting stones. His natural talent as a craftsman was quickly evident and he was made a freeman of the city of Coventry in 1841 at the age of just twenty-four. His interest, however, lay not in jewellery making but in larger scale metal-work which recreated the styles of the medieval period. In the early 1850s father and son left the jewellery business and committed themselves wholly to the manufacture of ‘ecclesiastical and domestic metalwork’. An advertisement placed in the Coventry Standard in March 1853 announced they were ‘selling off all their jewellery’ at very low rates. The decision, though risky, paid off. In recognition of his expertise on medieval metalwork, Skidmore was elected to the exclusive Oxford Architectural Society and in 1855 he was invited to design the roof for the new Oxford Museum. The opportunity to work on one of the most high-profile projects of the age demonstrated the renown he had already achieved.

Though influenced by the medieval period, Skidmore was also a technical innovator. A chalice shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851 featured the new technique of electroplating, whereby an electrical current was used to deposit a thin layer of silver onto another metal. He was also an early adopter of gas lighting which he installed in several buildings including Holy Trinity Church.

The best-known craftsman in the country

The 1860s saw the high point of Skidmore’s success. The Gothic Revival movement was at the height of its popularity, and he established a close working relationship with another leading proponent of the movement, the architect G. G. Scott. Throughout the decade the pair collaborated on many high-profile projects. A choir screen designed by Scott and made by Skidmore for Hereford Cathedral was hailed by visitors to the 1862 International Exhibition in London as ‘the grandest, most triumphant achievement of modern architectural art’. Skidmore drew on his background in jewellery making when constructing the screen, by incorporating other materials into its iron structure, he created a jewellery like effect on a large scale, and the result was like nothing seen before. At the exhibition he was awarded a special medal in metalworking, for ‘progress, elegance of design and excellent workmanship’. In 1864 he was Scott’s first choice to produce the metal work for the Albert Monument.

This success enabled Skidmore to open a large workshop on Alma street, on the site of what is now the Coventry University Alma Building. By 1865 he employed seventy-four men and fifty-four boys. The workshop included an extensive showroom, a large general workshop and pattern shops, and, reflecting Skidmore’s interest in new technologies, a photographic studio, electrotyping room and boiler house.

A decline in fortunes

Unfortunately, Skidmore’s fortunes began to turn for the worse in the 1870s. His skill as a craftsman, though unparalleled, ultimately impeded his success as a business man. As a former employee recalled, he was simply too much of a perfectionist: he 'worked for a good name, got the name, but lost money’ because of it. ‘He would break up goods of pounds and pounds in value just because they did not suit him in some trifling particular.’ This, coupled with a decline in commissions fuelled by the growing backlash against the Gothic Revival movement, led to Skidmore being forced to relinquish control of his company in 1872. Leaving Coventry, he established a new, much smaller, company in Meriden. Left unable to work for many years, and partially blind, due to an illness, he was eventually invited by London County Council to make alterations to the railings alongside the Embankment. The project, which should have revitalised Skidmore’s fortunes, ended in tragedy when, owing to his partial blindness, he was run over by a carriage. Skidmore was left unable to undertake the travel and manual labour essential to his profession and his new business also failed.

Returning to Coventry, and unable to work, Skidmore was forced to rely wholly on his freeman’s pension to support his family. In 1894 the Mayor of Coventry Sir Henry Acland, and several local clergy and gentlemen, formed themselves into a committee to assist Skidmore in his ‘declining years’. Enough money was put together to ensure that, along with the weekly sum he received under the freemen’s pension scheme, he was able to sustain himself and his family, albeit in severely reduced circumstances. Skidmore died aged seventy-three in his home on Eagle Street in 1896. Though he was laid to rest in ‘a very quiet manner’, the attendance of the mayor and several other local officials at his funeral, alongside the efforts made to maintain him in his final years, showed that Coventry had not wholly forgotten his skill and success.

Skidmore’s legacy

After his death, Skidmore's reputation as a craftsman continued to decline. The turn against the Gothic Revival movement continued well into the twentieth century and meant that much of his work was destroyed or removed. In 1897 the Hereford Screen was deemed ‘not so particularly artistic . . . a great deal too gaudy and glittering for its place’, and in 1967 it was removed from the cathedral altogether. It was sold to the Herbert Museum and Art Gallery, but the museum lacked the funds needed to restore it. In 1983 it was donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum but remained unrestored and out of sight.

In the late twentieth century, Skidmore’s work experienced a resurgence in popularity. In 1998 his work at the Albert Memorial was restored and two years later, in tribute to his contribution to Coventry, a plaque was unveiled on the site of the Alma street workshop. In 1993 a funding campaign was started to raise the money needed to restore the Hereford Screen, and in 2001 after the most expensive conservation project the Victorian and Albert Museum had ever undertaken, it was permanently installed in the museum. Positioned at the museum’s main entrance, it greets each visitor, finally according Skidmore, over a century after his death, the renown he was denied in his final decades. In the city in which he spent the majority of his life, Skidmore’s work is now also proudly displayed at the Herbert Museum and Art Gallery and in situ at Holy Trinity Church and St Mary’s Guildhall.

Bibliography

‘Death of Mr F. Skidmore’, Coventry Herald, 20 November 1896, p. 8.

‘F. Skidmore and Son’, Coventry Standard, 18 March 1853, p. 1.

‘Funeral of Mr F. A. Skidmore’, Coventry Evening Telegraph, 19 November 1896, p. 3.

‘Historian’s Corner’, Coventry Evening Telegraph, 21 September 1937, p. 7.

‘The Hereford Screen, by Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1862’, V&A Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-hereford-screen/ (17 September 2018).

Lepine, Ayla, ‘Resurrection, Re-Imagination, Reconstruction: New Viewpoints on the Hereford Screen’, British Art Studies, Issue 5 (April 2017). https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/hereford (17 September 2018).

Reeve, Matthew, ‘The Hereford Screen: A Prehistory’, British Art Studies, Issue 5 (April 2017). https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/mreeve (17 September 2017).

Robinson, Alice, ‘Collaborations Between Scott and Skidmore', British Art Studies, Issue 5 (April 2017). https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-05/arobinson (12 September 2018).

Whyte, William, ‘Skidmore, Francis Alfred (1817–1896)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 3 October 2013. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-69896 (12 September 2018).

Francis Skidmore at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum

Bible cover. Reference: SH.A.745.12 (see image on right)

Candlestick. Reference: SH.A.745.1

Cast Heads. Reference: SH.1949.227.423

Chalice. Reference: SH.A.745.10

Dish. Reference: SH.A.745.11

Door finger plate. Reference: SH.A.745.5

Iron work. Reference: SH.A.745.13

Lamp. Reference: SH.1987.11.2

Light Fitting. Reference: SH.1987.11.1

Mould. Reference: SH.A.745.7

Tray. Reference: SH.A.745.17

Vessel. Reference: SH.A.745.3

Francis Skidmore at Coventry Archives

‘A Study of the History of Ironwork’ by Geoffrey P Mankin, with particular reference to Francis Alfred Skidmore of Coventry. Reference: PA1785/1.

Correspondence with Julian W.S. Litten, senior museum assistant, Department of Prints, Drawings and Paintings, Victoria and Albert Museum, supplying him with information on F.A. Skidmore. Reference: CCB/1/14/296.

Press cuttings relating to Skidmore and his work. Reference: PA1785/2.

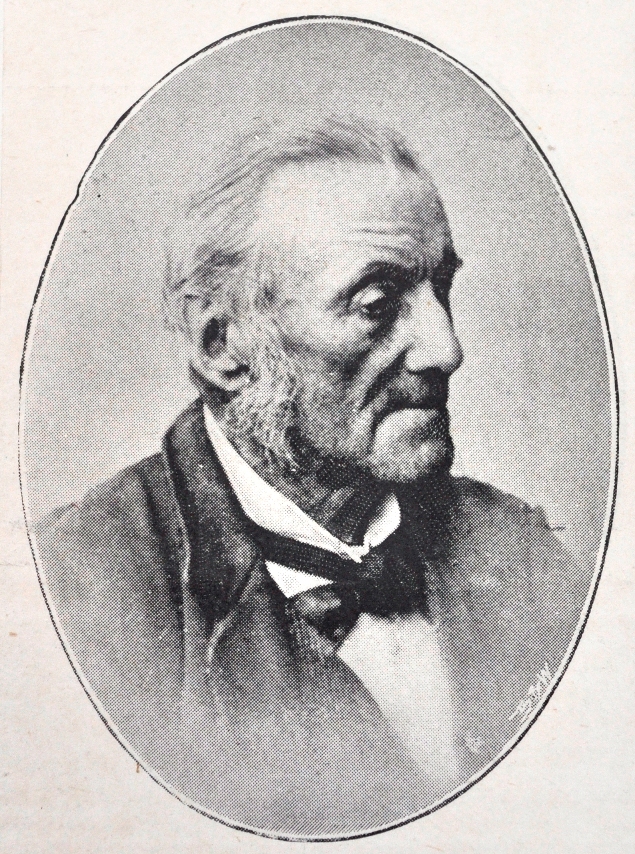

Francis Skidmore, 1896.

Francis Skidmore, 1896.

The Hereford Screen, 1862, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and made by Skidmore & Co. V&A Museum no. M.251-1984.

The Hereford Screen, 1862, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and made by Skidmore & Co. V&A Museum no. M.251-1984.

Enamelled and gilt Bible cover made by Francis Skidmore, circa 1864. Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, SH.A.745.12.

Enamelled and gilt Bible cover made by Francis Skidmore, circa 1864. Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, SH.A.745.12.