Writing Guides

The short guides on this page are aimed at helping you as you build your case for Associate Fellowship.

If you need further support at any point, please get in touch with either your mentor or Tom Hase in the first instance.

The guides are:

- Filling out the self-evaluation table

- Writing the narrative of professional practice

- Writing reflectively

There are also examples of completed Associate Fellowship applications for your reference.

Filling out the self-evaluation table

The self-evaluation table is important for two reasons:

- It helps you organise and qualify your various experiences relating to teaching in higher education; and

- It helps your assessors understand, along with your CV, the totality of your teaching experience. It is not assessed formally as part of the application process for Associate Fellowship but is required and is helpful.

Start by filling out as many of the boxes as you can. You don't need to write more than a sentence or two in each, but take time to think about what each of the dimensions of the UKPSF is asking and how your experience might map to that.

It is likely that you will be able to fill out some boxes in great deal but others might be more difficult and some you might feel you need to leave empty altogether. That is fine and by working through this table you will be able to help yourself identify the two Areas of Activity you will focus on for your Narrative of Professional Practice.

By completing the table you are also getting feedback on areas of your practice on which you might wish to focus on going forward. The UKPSF is a national benchmark for teaching in the UK (and, increasingly, in the English-speaking academic world) so these are the standards by which your teaching will be evaluated should you choose to stay in higher education.

Writing the Narrative of Professional Practice

The Narrative of Professional Practice (1400 words) is the key piece of writing that your assessors will use to evaluate whether your case for Associate Fellowship.

What makes up the Narrative

In the Narrative, you are asked to discuss, in detail, two of the five Areas of Activity, two key areas of Core Knowledge, and appropriate Professional Values. These are components of the UKPSF.

Areas of Activity are the 'what' of your teaching. They examine content and scope of your planning, the ways you teach, and how you build effective learning environments. You will need to select two of these to write about (although you will likely touch on the other three in some fashion as well).

The Areas of Activity are:

- A1: Design and plan learning activities and/or programmes of study.

- A2: Teach and/or support learning.

- A3: Assess and give feedback to learners.

- A4: Develop effective learning environments and approaches to student guidance and support.

- A5: Engage in continuing professional devleopment in subjects/disciplines and their pedagogy, incorporating research, scholarship, and the evaluation of professional practices.

Core Knowledge is the 'how' of your teaching. These points ask you to consider how you implement the Areas of Activity effectively and in a student-centred way. You will need to show that you understand your subject disipline and that you have thought about how you translate that understanding into effective classroom practice.

You need to demonstrate engagement with at least these two of the six elements of Core Knowledge:

- K1: The subject material.

- K2: Appropriate methods for teaching, learning and assessing in the subject area and at the level of the academic programme.

Professional Values represent the 'why' of your teaching. These points ask you to consider how you support your students, how you keep up-to-date with key developments in your field, and how you make equitable and forward-looking teaching environments.

There are four key Professional Values. You are asked to address these two explicity:

- V1: Respect individual learners and diverse learning communities.

- V3: Use evidence-informed approaches and the outcome from research, scholarship, and continuing professional development.

Writing reflectively

The key feature of the Narrative is that you do not simply describe what you do but rather critically reflect on how and why you do it. This means, practically, that you will need to write reflectively about your teaching.

Reflective writing may seem a strange and non-scientific way of approaching the information you need and you may never have been asked to write in this manner before. A number of models exist to assist with reflective writing. One you might find useful when approaching your Narrative is that proposed by Rolfe et.al. (2001).

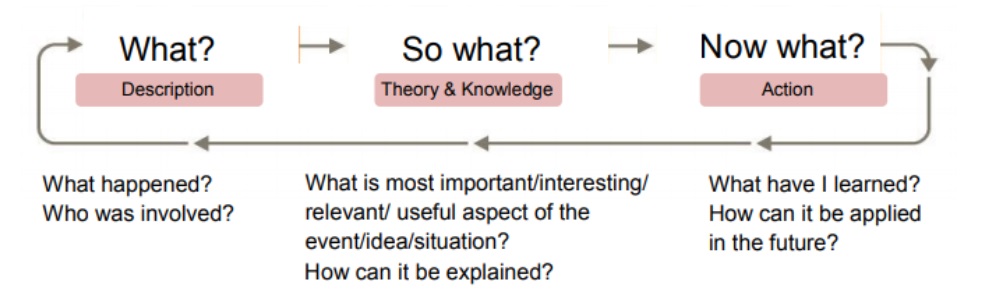

Rolfe suggests you structure your reflections by asking three questions: 'What?', 'So what?', and 'Now what?'.

Working through this pattern will help you establish the core of the point you are raising ('what') but then moves you into the critical reflective element ('so what'). Finally, it helps you position your reflection in the wider context of your teaching ('now what'). For the purpose of the Narrative, the 'so what' stage is most important. In this stage, you will take the description of a teaching decision you made and analyse it by demonstrating that you understand appropriate learning theory/departmental norms/disciplinary approaches. This is still unique to you -- you have identified the element you wish to discuss and you made specific decisions about how to approach the 'what' of the example -- but by demonstrating a link to wider theory and knowledge you move your example into a critical space.

Rolfe's model can be visualised in the following manner:

An example could be a decision you have made to try and make problems classes more interactive by asking students to do more hands-on work in the sessions.

An example could be a decision you have made to try and make problems classes more interactive by asking students to do more hands-on work in the sessions.

- What: Problems classes are often passive environments where I demonstrate solutions to problems on the board. Students rarely say anything and so I find it difficult to gauge whether the classes are useful or are helping them with their learning. Often the students just want to know 'the right answer' and I'm worried that this isn't building their problem solving skills.

- So what: The work of Marton and Saljo (1976) suggests that there are two key states of learning: surface and deep. Surface learning sees students only working to pass the test with little long-term retention of material or subject mastery. With deep learning, on the other hand, students become intrinsically interested in the material and work to really understand it at a fundamental level. A third state of learning -- strategic -- has also been proposed (Entwhistle and Ramsden, 1982) where students swap between surface and deep learning dynamically based on a variety of 'cues' in teaching sessions that they use to prioritise what is important to them and what isn't. Based on the very static and teacher-oriented problems classes I have been running, I think that most of my students are in the surface learning state or, at best, are adopting a strategic approach. I want them to become deep learners. Therefore, I have changed the approach of my classes to a structure where students work in pairs on an unseen problem that is very close to those assigned as homework. Then I ask the pairs to form into two or three larger groups (depending on overall class size) and compare their answers. I ask for volunteers to present their group solution before we collectively work the solution out on the board. Finally, we approach the homework questions where I am able to work through the answers in a way that links to the learning the students have just demonstrated. Thereby, the students do end up with the 'right answer' but they also have had the opportunity to learn from each other. The results have been very encouraging. Students were, initially, reluctant to participate and were worried they would be called out for any knowledge gaps or incorrect answers. By working with them, and choosing achievable examples for them to solve in the class, I was able to support them into this more active approach to their learning. I also ensured that at no point were individuals ever called on; everyone was always asked to talk about how their pair or group approached the problem, thus helping the less confident students while still providing challenge to those with further developed skills. Peer learning has been identified as a key factor in the success of physics undergraduates (Lasry, Mazur, Watkins, 2008) so I am keen to promote this in my own classroom.

- What next: Based on student feedback these revised problems classes appear to have been beneficial. Assessment results for my groups have been improving and students report that their confidence is improving as well. Some are still frustrated that we are not just discussing the 'right answers' but I hope that through introducing my approach more clearly next year I will help address these concerns. I will also make sure that I am clearer on the fact that we will be discussing the homework answers explicitly, just after we work through the skills.

Examples

The following are successful cases for Associate Fellowship made by member of the Department of Physics. They may be useful to help you frame the scope and nature of your own writing. Your case, however, will be unique to you. That means that these examples are indicative only; you will need to work through what the UKPSF is asking in light of your own experiences, perspectives, and priorities. (Examples are provided for your reference only, with the permission of their authors. They are not to be copied or shared.)

- Example 1

- Additional examples will be added shortly