Communities, Territory and Cure of Souls: Parishes in Late Medieval Aosta

Elena Corniolo (Università degli Studi di Torino)

The organization of the cure of souls in the city of Aosta in the late Middle Ages demonstrates the profound relationship between churches, territory and inhabitants. This case study is interesting because the churches with cura animarum served specific areas of the city, but they also reflect a hierarchical dimension, which involved not only the local population, but also the two main ecclesiastical institutions: the cathedral chapter and the chapter linked to the Augustinian priory of S. Orso.

The starting points for this exploration of the neighbourhoods and parishes of Aosta in the late Middle Ages are the pastoral visitations made by the bishops of Aosta in the fifteenth century [1]. Through these sources we can identify four churches with parish functions within the territory of the current municipality of Aosta: S. Giovanni, S. Lorenzo, S. Stefano and S. Martino di Corléans.

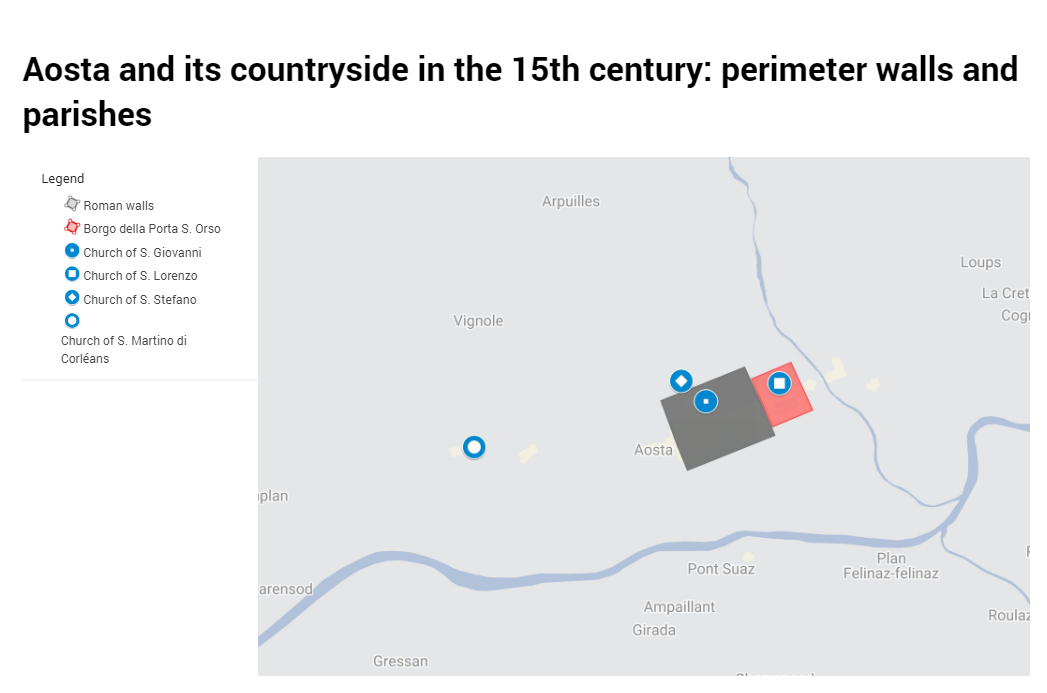

Today, the first three churches are in the historical centre and the fourth in the western suburb of Aosta. In the period covered by the sources, however, the setting was different. S. Giovanni was situated inside the ancient part of the city, within the perimeter of the Roman walls, while S. Lorenzo and S. Stefano could be found just outside, respectively in the eastern and in the northern parts of the areas into which the city had expanded in the eleventh century. S. Lorenzo church belonged to a district called borgo della Porta S. Orso, which was surrounded by its own defensive walls and situated along the road leading to the Po valley. S. Stefano also lay on an important traffic artery connecting to the Great Saint Bernard pass. In the fifteenth century, the church of S. Martino could be found further along the route towards the Small Saint Bernard pass, in a still rural area dominated by the cultivation of vines (see Map 1).

Map 1. Both maps have been drawn by the author using My Maps (by Google).

The rural church of S. Martino belonged to the bishop of Aosta until 1248, when it came into the possession of the Augustinian canons of Verrès, who administered it until 1488 [2]. The three other parishes, in contrast, were controlled by the two city chapters: the secular chapter of the cathedral chose the priests of S. Giovanni and, from 1234, those of S. Stefano; the regular chapter of S. Orso those of S. Lorenzo and, until 1234, the parsons of S. Stefano [3]. The main matrix of the urban cure of souls involved the two city chapters and the parish churches of S. Giovanni and S. Lorenzo. The relationship between the former and the latter was similar in both cases – the canons presented their preferred priest to the bishop, who then invested them with the cura animarum – but the spatial arrangement of the churches was different. In fact, S. Lorenzo was located in front of the priory of S. Orso: the two buildings were very close, but still distinct. The altar of the parish of S. Giovanni, however, was inside the cathedral of S. Maria, the church which hosted the choir of the secular canons. This arrangement affected lay identity. Reading the pastoral visitations, it seems that cathedral affairs took priority over parish life. In fact, only one visitation mentions the parish altar, however the church was inspected three times [4]. For the ecclesiastical authorities, the main altar was that of S. Maria, the patron saint of the cathedral [5]. The ranking of two altars is evident in the pastoral visitation of 1416: «they went to the place of the chapter (…) they returned to the main altar (…) they went to the altar of S. Giovanni» [6]. In addition, the visitors do not mention the baptismal font belonging to the parish of S. Giovanni, implying that the ecclesia mater of the cathedral absorbed the sacramental autonomy of the parish of S. Giovanni. In this period, furthermore, the cathedral looked very different: it had two apses, one at the end of the east side of the main nave, the other on the west side, i.e. one for each altar (S. Maria and S. Giovanni), and four bell towers, two for each apse [7]. Today we can see only one main apse with two bell towers (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The two bell towers of the cathedral of S. Maria, Aosta. All photographs by the author.

Fig. 2. The northern side of the church of S. Orso and the bell tower of the priory’s church.

Zooming in on the urban context, it seems that the three churches served three different districts of the city: people who lived within the Roman walls were linked to S. Giovanni, those of the borgo to S. Lorenzo and those who lived in the northern part of the city to S. Stefano. The cathedral chapter thus supervised the cure of souls over most of the city's territory. However, the pastoral visitation of 1416 complicates this framework. Referring to S. Stefano, the bishop’s secretary wrote: «the sacramentalia are kept in the church of S. Giovanni (…). There is no baptismal font» [8]. Clearly, while able to worship and to take communion in S. Stefano, the people of this parish had to go to S. Giovanni to receive baptism [9]. It was not a problem in terms of mobility – the two churches were really close to each other and the road was easy to travel – but it was a clear sign of subordination.

Fig. 3. The current eighteenth-century facade of the church of S. Stefano in Aosta.

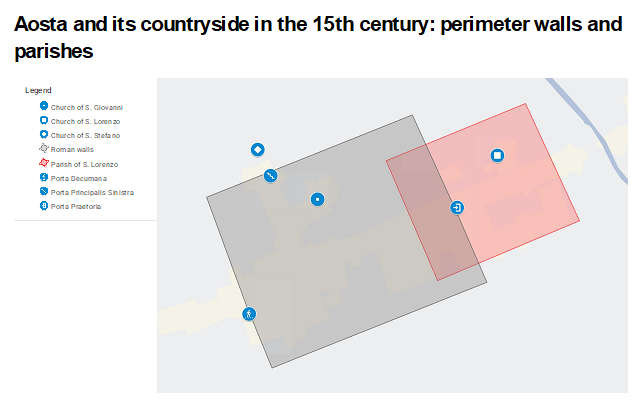

On the other hand, considering that «the baptismal font drips in two places» [10], the fifteenth-century parishioners of S. Lorenzo in the borgo could receive all sacraments in their own church. This spiritual independence, however, was a recent achievement: until 1387, the only font in the entire city had been that of S. Giovanni. Discussions about baptismal rights and parish borders between the two city chapters had in fact started in the previous century. In 1233 both decided to appeal to an arbitrator, with the purpose of putting an end to their dispute. The decision, which proved a source of further conflicts, altered the boundaries within the perimeter of the Roman walls: the parish of S. Lorenzo, under the canons of S. Orso, extended its jurisdiction into the ancient city [11]. It was not by chance, I argue, that the following year, the two chapters agreed to exchange the administration of two churches, that of S. Stefano of Aosta and that of S. Stefano of Chevrot. As a result, the cathedral canons enhanced their bond with the city, while those of S. Orso strengthened their presence in the countryside south of the city, where they owned goods and farms already. The reduction of S. Orso’s influence in the north of the city in turn increased the old centre’s ties with the borgo and its inhabitants, both in the economic as well as the ecclesiastical spheres. The canons of S. Orso became the main landlords in the area, and the religious point of reference for its inhabitants. The baptismal font erected in the church of S. Lorenzo, according to a pronouncement of the diocesan official dated 2 July 1387, fits into this context [12].

Map 2. From 1233, the boundary of the parish of S. Lorenzo (red area) crossed the line of the Roman walls.

The evidence from the pastoral visitations of the fifteenth century also allows us to reconstruct the internal arrangements of the churches, for example the presence of specific local communities, fraternities, aristocratic families. This would be another topic worth exploring. However, even though this post focused on territorial decisions made by clerical authorities, it is important to point out that local communities were not passive. Much rather, they were able to use the setting of the church and also the relationship with different political actors to create their own space for social and political action.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Elena Corniolo is a research fellow at the University of Turin and a high school Italian and History teacher. Her research interests include the local Church and the dynamics of community formation and interaction in late medieval North-Western Italy. She received her Phd from the University of Turin, where she studied with professor Luigi Provero. Her doctoral dissertation, focusing on the history of the priory of Sant’Orso in the 15th century and its relationship with the bishop of Aosta, was published as Chiesa locale e relazioni di potere nel XV secolo. Sant’Orso d’Aosta tra il 1406 e il 1468 (2019, Milano: FrancoAngeli).

ENDNOTES

I thank Beat Kümin for his help with the English text.

[1] The relevant documents are preserved in the Diocesan Archives of Aosta, reg. 3 (Visites pastorales de la Cathédrale et de la Collégiale). They were edited by Marie-Rose Colliard in 2015: Marie-Rose Colliard, ed., Atti sinodali e visite pastorali nella città di Aosta del XV secolo (Aosta: Tipografia valdostana, 2015).

[2] Brunod Edoardo, Diocesi e comune di Aosta (Quart: Musumeci, 1981), 260.

[3] Ibidem, 234; Paolo Papone and Viviana Vallet, “Storia e liturgia nel culto di Sant’Orso”, Bulletin Société académique religieuse et scientifi que du Duché d’Aoste (Bulletin Académie Saint-Anselme), 7 n.s. (2000): 220-259.

[4] In 1416 and 1422 by the bishop of Aosta; in 1427 by the archbishop of Tarentaise (Colliard, Atti sinodali, 115-147). The altar of S. Giovanni was visited only in 1416 (Ibidem, 116).

[5] «Intravimus usque ad altare magnum accedentes ubi, finita dicta antiphona, diximus orationem Beatae Mariae Virginis, sub cuius vocabulo dicta ecclesia est et fuit fundata» (Ibidem, 129. Pastoral visitation of 1427).

[6] «Inerunt ad locum capituli (…) retroceserunt ad magnum altare (…) inerunt (…) ad altare Sancti Johannis» (Ibidem, 116-117).

[7] Mauro Cortelazzo and Renato Perinetti, eds., La Cattedrale di Aosta: dalla domus ecclesiae al cantiere romanico (Aosta: Gruppo Inva, 2007), 50-51.

[8] «Sacramentalia servantur in Sancto Johanne Augustensi ubi batizantur omnes parrochiani, et ipsa est de gremio ecclesie. Fontes non sunt» (Colliard, Atti sinodali, 215). Sacramentalia means the sacred oils.

[9] We know that people could receive communion because the pastoral visitations record where the hosts were kept (for example: «Corpus Domini servatur infra unum tabernaculum et in una pisside lotoni cum cruce, infra sunt circa XVII hostie», Ibidem, 214; pastoral visitation of 1413).

[10] «Fons baptismatis stilat in duabus partibus» (Ibidem, 152).

[11] Orphée Zanolli, ed., Cartulaire de Saint-Ours. XVe siècle (Aosta: Imprimerie valdôtaine, 1975), 340-346, doc. 625.

[12] Archives of S. Orso, 4F7-6.