A night’s stay and some travel money: Passing through the city of Leiden in the Netherlands, 1803-1834

Marjolein Schepers

On 29 January 1824, two ‘foreign craftsmen’ received 10 stuyvers from the city of Leiden. We don’t know their names, professions or origins. These strangers appear among 23 entries of individuals, households or small groups of people who received some passanten relief from the city that month according to the passanten registries. The Leiden city archives contain an early nineteenth-century register with daily expenses to passanten, people travelling and, from the perspective of the city, simply passing through. This source provides insights into the relations between the city and the Protestant deaconry and into the attitudes of communities to mobility and unsettledness.

The registers in the archives of the city of Leiden extend from 1803-1834 and document the income and spending of the passantmeester during these years, i.e., the relief provided by the ‘master for those passing through’. In the Low Countries, references to the concept of passanten can be found from the medieval period onwards, denoting people who passed through the city without the intent of staying. It was not a universal legal concept, but instead it designated the difference between residents and people passing through. Passanten were on the move, like pilgrims or merchants or people travelling for family visits, itinerary migrants or labour migrants, and only stayed briefly in the community while in transit, for example to take another barge or coach, or to rest after a day’s walking. But although the individuals only stayed briefly, as a whole they can be considered as a separate social group in cities, for which distinct facilities and policies existed. To date, scholarship on mobility and migration has only touched on the phenomenon in passing.

The concept is rooted in Christian and Jewish notions of hospitality and charity. People were supposed to host fellow believers who were traveling overnight and provide them with a meal. Remnants of formalized provision can be found in several cities in the Low Countries, like the Sint Juliaans Passantenhuis in Mechelen or Hospitaal Sint Joos in Bruges. Other common names for these houses were passantengodshuis or baaierd. Leiden had two baaierds, which in this case were distinct establishments within larger gasthuizen (hospitals) to host travellers amongst others, or, in the case of the Sint-Elisabethsgasthuis, poor homeless women. The passanten institutions generally merged with other hospitals and relief institutions and by the eighteenth century they often fell out of use, or were replaced with passantengeld, a sort of relief which often took the form of travel vouchers. These historical facilities for passanten were the results of considerations of charity on the one hand and social control on the other. Although passantenhuizen offered a free night’s stay, they also allowed urban authorities to host all travellers in one place for monitoring reasons. And while travel vouchers allowed migrants to continue their travels, they also helped to ensure that visitors would not remain in the city or become destitute within the city boundaries, but instead would carry on to their next destination.

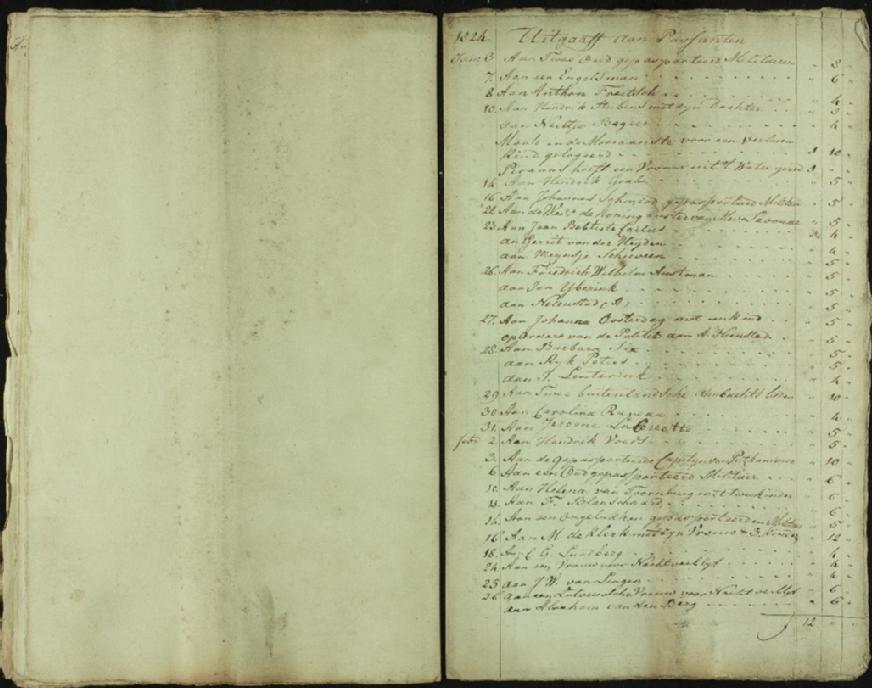

Image 1: Excerpt of expenses for the year 1823 in the register of the passantmeester in the city archives of Leiden.

Erfgoed Leiden, Stadsarchief III, inv. nr. 1919. Scans made available by Erfgoed Leiden.

The Leiden registries are rather detailed, but the information differed between entries. The largest part of the archival source consists of lists with the total amounts of money spent per month, but for the years of 1823, 1824 and 1834, we find more elaborate ‘states of expenses’. These include daily entries with the names or descriptions of people to whom relief was provided by the passantmeester. Some of the entries stand out because they include a general description rather than a name, such as ‘passported soldiers’ or ‘travelling craftsmen’. At times the reason for provision was mentioned, such as travel money, or a nights’ stay. The passantmeester noted having spent 8 stuyvers on 16 January 1823, ‘to a Man Sreuder with his wife, coming from England, for a nights’ stay’. On the following day, he gave another 8 stuyvers ‘[t]o the same Jan Sreuder with his wife for a night’s stay’. And on 18 January, ‘[t]o the same, travel money’, totalling 4 stuyvers, plus 2 guilders and 4 stuyvers for ‘half board [halfvracht] on the Postal roads to Haarlem’.

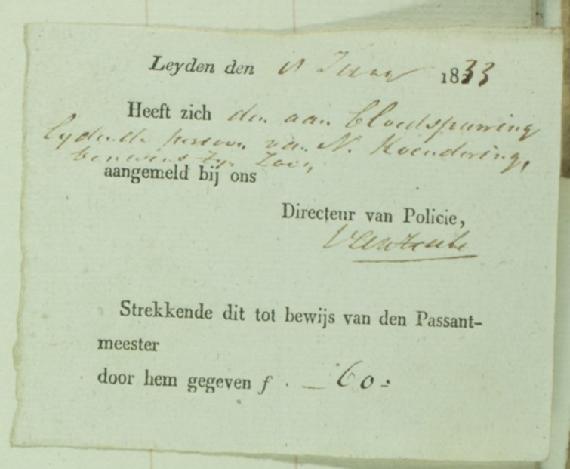

Additionally, the register contains some receipts which the passantmeester had reimbursed. They provide insights into how this relief was distributed, often by the local police. The receipts have a higher level of detail, but only a few of them survive in the archive. Most of these were small, printed slips completed by hand, which implies that it was a standardised procedure. The form stated: ‘Leiden, on the … of 18… / ….. have presented themselves to us / Director of Police ….. / This functioning as proof that the Passant master / has given him f. [guilders] ….’

Image 2: Receipt from the passanten registries, 1833. Erfgoed Leiden, Stadsarchief III,

inv. nr. 1919. Detail of scan made available by Erfgoed Leiden.

The Leiden registers are remarkable because they provide evidence of continuity in the nineteenth century. And while historians like Jan de Vries or Joke Spaans already documented the existence of passantengeld in the form of travel vouchers for barges transport, here we find evidence of varying forms of relief. Exploratory research in other cities in the Low Countries, including Belgium, showed that similar registries were kept in the city of Mechelen in Belgium in the early nineteenth century. There, however, they resemble passport and visa registers of the same period, documenting – in more detail than at Leiden – information like places of origin, destinations and itineraries of people arriving in or passing through Mechelen. While featuring an extra column on relief provided to travellers, the amount was filled in only sporadically and without further details on the kind of help offered.

Although more research is needed to contextualise the source genre properly, it seems clear that relief was not just targeted at the local parish community but also at travellers and migrants. Instead of focusing on residents, relief for passanten had a more differentiated public urban function. It involved religious parish officials as well as civic authorities. The passantmeester was a civil servant acting on behalf of the Huiszittenhuis, the urban relief institution of the Dutch Reformed church (more specifically, its deaconry) which was governed by parishioners dealing with the social aspects of the parish (diakenen) and municipal regents. Relief provided to passanten was financed by the city rather than parochial funds. The implementation and daily operations however were in the hands of the Reformed deaconry.

Image 3: ‘Huiszittenhuis van de Hervormde Diaconie’. The Huiszittenhuis – freely translated as ‘house of outdoor relief’ –

was the poor relief institution of the Reformed deaconry, located at Oude Rijn 44 in Leiden.

Drawing in colour by Jacob Timmermans, 19,5 x 29,2 cm, 1788. Erfgoed Leiden.

The wider functions of the passanten registers also emerge from the religious profile of the recipients. The passantmeester did not just cater to the Protestant community. We might assume that the aforementioned Sreuder and his wife, were members of the Church of England or perhaps nonconformists rather than members of the Dutch Reformed church. There is also mention of a Jewish traveller in the sources. Relief in the early modern Dutch Republic and the nineteenth-century Kingdom of the Netherlands more generally was however divided between religious communities. The Protestant relief institution, as part of the ‘official’ Church, was generally responsible for public relief and people of other religions had to turn to their own congregation. Yet there were significant local differences. Maarten Prak, for example, has demonstrated that the city of Den Bosch made public relief available to people from all denominations. In addition to the religious distinctions, relief was also organised along domicilie van onderstand, known in a British context as the laws of settlement.

In the words of the historian G.P.M. Pot, in eighteenth-century Leiden ‘beggars, passanten and immigrants were in essence equated in terms of policies. They formed a burden and a danger and therefore had to be monitored and regulated.’ (1997, p. 87) This reflected fears of political unrest and uncontrollable numbers of beggars as well as a desire to preserve the urban order. Pot thus understood these policies in terms of social control. But did passanten policies only target poor travellers? Based on categorisations of wealth according to profession, passported soldiers or travelling craftsmen are different categories from – for example – a single mother and her children. To what extent was the concept of passanten, then, limited to poor people on the road? Should we perhaps view it as referring to more mixed groups of pilgrims, craftsmen, merchants as well as the destitute? Moreover, the receipts included in the archival source also indicate reimbursements to Leiden natives resident in nearby Leiderdorp. Further research into the archives of the Huiszittenhuis and the Leiden city council is needed to establish whether the passantmeester had a double function, of caring for passanten in Leiden and those from Leiden elsewhere, or whether this double function instead related to caring for passing travellers (of various status) and the local poor.

David Hitchcock found similar dynamics in the aid systems for travellers in early modern Warwickshire. There, local constables oversaw distributing relief to ‘passengers’ and ‘poor passengers’, in addition to implementing the vagrancy laws, by expelling or punishing vagrants. Hitchcock convincingly showed how the typologies of travellers in these different categories, those to be helped and those to be punished, did not only relate to structural, socio-economic elements but also depended on the constables themselves, who held discretionary power.

Image 4: ‘Gezicht op de Witte Poort te Leiden’ [View on the White Gate in Leiden], etching and engraving

attributed to Andries van Buysen (Sr.), 14,5 x 19 cm, 1734. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

The relationship between relief and migration regulation is a contested topic. Support provided to passanten, and to poor ‘passengers’ for that matter, nevertheless appears to have functioned as an encouragement to move on, for continuing on the road. It prevented migrants from settling in the community or becoming dependent on relief there. In that sense, the passanten relief is comparable to restrictive migration policies in other cities. Marco van Leeuwen, for example, argued that the city of Amsterdam eased regulations for migrants to enter the city in the nineteenth century but limited their access to poor relief. Anne Winter on the other hand found that nineteenth-century Antwerp prevented poor migrants from entering the city by introducing strict requirements on identity documents. More research into relief, facilities and policies regarding passanten – not least on the precise role of the parishes – is needed to provide further insights into the entanglement of migration policies and poor relief in this case. The functions of passanten relief so far appear to span forms of charity or solidarity for co-believers as well as forms of social control or monitoring of migrants. The deconstruction of categories and typologies of migrants and travellers based on such sources will help further our understanding of this supposed dichotomy. But the passanten registries discussed offer much more – not least a perspective on cities and villages as places that people passed through. They form a rich source for research into transient migration, i.e. the continuous stream of people arriving and leaving local communities in the period around 1800.

Primary Sources

City Archives of Leiden (Erfgoed Leiden), Stadsarchief III, 1919, ‘Register van inkomsten en uitgaven van de passantmeester, kasboek en enige bijlagen betreffende bijstand voor passanten, 1803-1834’.

Further Reading

Chopra, Preeti, ‘Worthy Objects of Charity. Government, Communities, and Charitable Institutions in Colonial Bombay’, in Prashant Kidambi, Manjiri Kamat and Rachel Dwyer (eds.), Bombay before Mumbai: Essays in honour of Jim Masselos (Oxford 2020) 171-193.

Hitchcock, David ‘A typology of travellers: migration, justice, and vagrancy in Warwickshire, 1670–1730’, Rural History 23:1 (2012) 21-39.

Leeuwen, Marco H.D. van, ‘Overrun by hungry hordes? Migration and poor relief in the Netherlands, sixteenth to twentieth centuries’, in Steven King and Anne Winter (eds.), Migration, Settlement and Belonging in Europe: 1500 to 1930s (New York 2013) 173-203.

Moatti, Claudia and Wolfgang Kaiser (eds.), Gens de passage en Méditerranée de l'Antiquité à l'époque moderne : Procédure de contrôle et d'identification (Paris 2007).

Pot, G.P.M., Arm Leiden. Levensstandaard, bedeling en bedeelden, 1750-1854 (Hilversum 1994).

Pot, G.P.M., ‘Het beleid ten aanzien van bedelaars, passanten en immigranten te Leiden, 1700-1795’, Jaarboekje voor Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde van Leiden en Omstreken 79 (1997) 82-95.

Prak, Maarten, ‘Goede buren en verre vrienden: De ontwikkeling van onderstand bij armoede in Den Bosch sedert de Middeleeuwen’, in Henk Flap and Marco H.D. van Leeuwen (eds.), Op lange termijn: Verklaringen van trends in de geschiedenis van samenlevingen (Hilversum 1994) 147-69.

Schepers, Marjolein, ‘Just Passing Through? Onderzoek in uitvoering naar passanten en infrastructuren voor transitmigranten in de Lage Landen, 1780-1870’, Stadsgeschiedenis 16:1 (2021), 66-80.

Spaans, Joke, Armenzorg in Friesland 1500-1800: publieke zorg en particuliere liefdadigheid in zes Friese steden Leeuwarden, Bolsward, Franeker, Sneek, Dokkum en Harlingen (Hilversum 1997).

Vries, Jan de, Barges and Capitalism. Passenger Transportation in the Dutch Economy, 1632-1839 (Wageningen 1978).

Winter, Anne, ‘Eigen armen eerst? Migranten en de toegang tot armenzorg in Antwerpen, c. 1840-1900’, in Margo De Koster, Bert De Munck, Hilde Greefs, Bart Willems, and Anne Winter (eds.), Werken aan de stad. Stedelijke actoren en structuren in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, 1500-1900. Liber alumnorum Catharina Lis en Hugo Soly (Brussels 2011) 135-156.

Winter, Anne, ‘Settlement law and rural-urban relief transfers in nineteenth-century Belgium: A case study on migrants’ access to relief in Antwerp’, in King and Winter, Migration, settlement and belonging, 228-249.

Biographical note

Marjolein Schepers is a postdoctoral research fellow in History of the Research Foundation Flanders, affiliated to Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Ghent University. In the framework of her ongoing research on migration, welfare and the parish, as well as migration infrastructures in eighteenth and nineteenth century Low Countries, she currently holds an IAS Fernandes visiting research fellowship at the University of Warwick allowing collaboration with Beat Kümin, Rosa Salzberg and Felicita Tramontana and the Warwick Network for Parish Network, including co-organization of the 2021 Parish Symposium and of a workshop on Passanten and transient migration in early modern Europe.