'A Grim Spectacle': The Migration of ‘Irish’ Refugees in the City of London, 1641-1651

Bethany Marsh

University of Nottingham

bethany dot marsh at nottingham dot ac dot uk

On 23 October 1641 armed rebellion broke out in Ireland. Planned by members of the Irish Catholic elite, such as Sir Phelim O’Neill and Rory O’Moore, the rebellion was to consist of two inter-connected parts. Firstly, Dublin Castle was to be seized, removing English administrative control over Ireland, and secondly a series of fortifications in Ulster were to be captured. These plans, however, were never realised fully. The Lord Justices of Ireland were informed of the intended insurrection on 22 October allowing them to arrest a number of the chief conspirators, including Lord Maguire and Hugh MacMahon. Dublin was deemed safe, but what was designed to be an organised rebellion conducted by the Irish elite transformed into a violent conflict between predominately Native Irish Catholics and English Protestant settlers and later Scottish Presbyterian settlers, resulting in thousands of Protestant refugees fleeing to England, Scotland and the Continent.

In England, refugees migrated across the country in search of subsistence and security. Many travelled to London in search of aid from family and friends, to petition parliament for relief or to resettle inconspicuously amongst the city’s population of approximately 400,000 inhabitants. While it is difficult to estimate how many refugees exactly sought relief in the capital, a report drawn up by city of London officials in the late summer of 1643 complained that at least five hundred destitute ‘Irish’ refugees were congesting the streets. This is a conservative figure for the city of London. A sample study of thirty parishes shows that a minimum of 408 refugees were being aided between March 1643 and March 1644 by parish officials, namely churchwardens and overseers of the poor. For the capital as a whole – the city of London, city of Westminster and the adjoining areas of Middlesex and Southwark – there were certainly many hundreds more seeking assistance.

The largest contingent of refugees received relief in the first year after the rebellion. In the winter of 1641/2 fifty-nine refugees were aided in St. Dunstan-in-the-East, fifty-two in St. Dunstan-in-the-West and sixty-one in St. Mary Abchurch. Later migration patterns of refugees in the city of London emulated developments in the conflict in Ireland. An example would be the effect of the Cessation of Arms which was signed in Ireland on 15 September 1643. The truce between the Royalists and the Irish Confederates brought relative peace to parts of Ireland and consequently the number of refugees fleeing to England decreased. This was reflected by a fall in the number of refugees receiving relief across England. In Upton, Nottinghamshire, the number of refugees fell from forty in 1643/4 to seventeen in 1644/5. Similarly in Bressingham, Norfolk, the number of refugees given aid fell from sixteen to two between these years. In London, in Dunstan West, the number of refugees receiving relief fell from 267 refugees in 1643/4 to fifty-four in 1644/5.

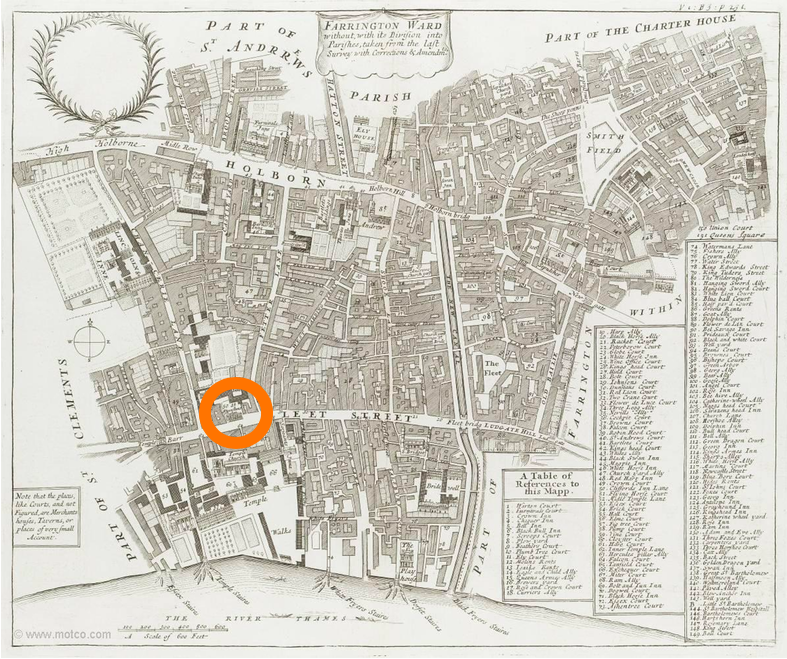

Topography also affected the migration patterns of refugees. Parishes close to particular roads or the main London docks helped greater numbers of distressed people from Ireland than other parts of the city. Between 1641 and 1651 the churchwardens of Dunstan West, for example, aided a minimum of 510 refugees. The parish, see figure 1, was located along one of the capital’s busiest thoroughfares, Fleet Street. Fleet Street was a continuation of the Strand, connecting the city of London to the city of Westminster. Westminster was the centre of political power, being the site of the Royal Court, the Court of Burgesses and the two Houses of Parliament. The city of London was the economic centre, having the Guildhall, the Royal Exchange and the port of London. As refugees travelled between these two important areas of the capital many stopped at the church for charitable donations. On 27 October 1648, for instance, Edward Bishop, an elderly religious minister from Ireland, was given two shillings by the churchwardens. He had been wounded by the Irish rebels and ‘a peece of his skull [was] taken out whereby his memory so faileth him that he is utterly disabled in his function who hath a Testamoniall there so from the Councill at Dublin and is thereby recommended to Charity’. Dunstan East, figure 2, meanwhile, was situated in close proximity to the main London dock, in the adjacent parish of St. Mary-at-Hill. As refugees disembarked, in the capital, they would have looked to this, the closest parish church, for subsistence. Consequently, between 1641 and 1651 the churchwardens there gave one-off donations to a minimum of 305 refugees. Thomas Warwell and his nine children, for example, were given two shillings on 21 February 1642. Mary Gwin was given one shilling on 28 July 1646, her husband having been ‘slain in Ireland’, and on 15 November 1649 two ministers, Mr Freeman and Mr Turner, received one shilling in relief.

The flow of refugees in and out of the City was continual throughout the 1640s and so their presence was highly visible. Refugee numbers varied considerably across the City, often based upon the geographical location of each parish and developments in the conflict in Ireland. Other factors which influenced migration also included the wealth of a parish’s parishioners and the number of dependants being maintained by the claimant. Numbering in their hundreds, if not thousands, refugees, alongside other distressed and displaced people from across England, congested the streets of the capital making interaction inescapable and their plight obvious. They no doubt formed a grim spectacle.

Figure 1: ‘Parish map of St. Dunstan-in-the-West’ in John Stow, A Survey of the cities of London and Westminster written at first in 1598; much enlarged, and brought down from the year 1633 to the present time by John Strype (London, 1720), III, p. 231, https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/index.jsp, reproduced from

Motco Enterprises Limited (www.motco.com); accessed 05/07/2018.

Figure 2: ‘Parish map of St. Dunstan-in-the-East’ in John Stow, A Survey of the cities of London and Westminster written at first in 1598; much enlarged, and brought down from the year 1633 to the present time by John Strype (London, 1720), II, p. 29, https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/index.jsp, reproduced from

Motco Enterprises Limited (www.motco.com); accessed 05/07/2018.

Bethany Marsh is a PhD Student at the University of Nottingham, completing a thesis on ‘"Protestant martyrs or Irish vagrants?" Charity and the organisation of relief to Irish refugees in England, 1641-1651'. She is an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and winner of the Midland History essay prize 2016.

This post discusses elements of her contribution to the 'Parishes and Migration' symposium in May 2018.

It is also available in Word format.