A Universal Language?

One of the ever-present problems in any science fiction which addresses the interaction between two and more cultures is that of communication. If there is no common point of reference or shared vocabulary, establishing a mutually meaningful level of communication will be a challenge. One possible source of commonality that SF has explored is the idea that science, and its underlying mathematics, provides a universal language.

As early as the beginning of the seventeenth century, Galileo Galileo was able to declare that “Mathematics is the language in which God has written the Universe”. Whether or not deity is involved, the view of modern, Western scientific culture has not changed from this early stance: the Universe as we understand it can be described by a complex series of mathematical rules and physical laws which we believe to apply regardless of location or perspective.

An interesting use of this principle in SF, dating from the dawn of the Space Age, can be found in the 1957 short story Omnilingual by H. Beam Piper [1]. This story follows the efforts of archaeologists trying to uncover a Martian civilisation which died off fifty thousand years before humanity reached the planet. One of the team focuses on trying to systematise surviving examples of the Martian script, attempting to find plausible translations. Based on experience on Earth, her colleagues insist that this will be impossible without a bilingual text - a record which presents the same words in both Martian and an Earth language, as the Rosetta Stone did with hieroglyphics, demotic and ancient greek. In this case, such a text seems self-evidently impossible to obtain. The discovery of a university, and particularly its science department, provides a breakthrough in the form of a recognisable and well labelled periodic table.

Setting aside the impossibility of the Martian climate and civilisation as described (which was already known to be unlikely in 1957 and finally ruled out by later probes), this story makes a good case for scientific data, combined with careful systematic analysis, providing a point of commonality between cultures separated by both space and time. It’s arguable that the archaeologists get somewhat lucky: the language being translated is far more regular than English, and contains simplifying elements such as months which are numbered rather than named. This has been true of certain dating systems in the past (we inherited Septem-, Octo-, Novem- and Decem- ber named as the seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth months from the Romans) but does not allow for any of the irregularities that arise as a civilisation develops, peaks and declines. Nonetheless, the basic principle that an atom of hydrogen is an atom of hydrogen anywhere is hard to contest.

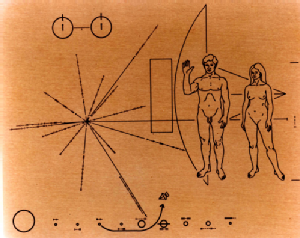

The same principle has also appeared in human efforts at SETI (the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence). The Pioneer spacecraft launched in 1972 and 1973 were designed to ultimately leave the Solar System and were equipped with illustrated plaques designed to communicate key information to any extraterrestrial life which encountered them. Some of the same notation was also used on the cover of golden phonograph records which were launched with the Voyager probes in 1977. The records themselves digitally encoded images and audio recordings which could be translated in part with the aid of this data. The basic scientific key in both included the atomic structure of hydrogen and also a map which positioned Earth with reference to bright pulsars (spinning neutron stars which emit a distinctive signal). These are identified by their frequencies using a binary notation which is itself calibrated against a key feature of the hydrogen atom (its hyperfine transition which causes bright emission at radio frequencies).

The same principle has also appeared in human efforts at SETI (the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence). The Pioneer spacecraft launched in 1972 and 1973 were designed to ultimately leave the Solar System and were equipped with illustrated plaques designed to communicate key information to any extraterrestrial life which encountered them. Some of the same notation was also used on the cover of golden phonograph records which were launched with the Voyager probes in 1977. The records themselves digitally encoded images and audio recordings which could be translated in part with the aid of this data. The basic scientific key in both included the atomic structure of hydrogen and also a map which positioned Earth with reference to bright pulsars (spinning neutron stars which emit a distinctive signal). These are identified by their frequencies using a binary notation which is itself calibrated against a key feature of the hydrogen atom (its hyperfine transition which causes bright emission at radio frequencies).

(Image above: Pioneer plaque, source: NASA; Image below: Voyager golden disk cover, source: NASA)

While the plaques and records were explicitly designed to be as culture-neutral as possible, they have been criticised for culture-specific devices such as arrows and a waving hand. There has also been some discussion as to whether the two dimensional line-drawings of three dimensional systems (such as the hydrogen atom or local space) themselves represent culturally-constrained conventions (in the same way that an image of Earth’s spherical surface may appear unfamiliar when seen in a different geometric map projection). The issue here is not whether the properties of hydrogen are universal, but whether they can be represented in a universally recognisable manner.

These questions were asked in a subtly different way in 1974 (contemporary with the probe images) when a message designed by Frank Drake and others was transmitted from the Arecibo radio telescope dish, specifically with the intention of contacting aliens. Inevitably, scientific and mathematical notation was used, with the transmission attempting to communicate binary notation, atomic structures, the nature of DNA and prime numbers as well as a representation of humanity. In this case, the information was transmitted as a continuous signal which could be rendered into a pixelated black and white image by arranging the data into a prime-by-prime-number rectangle. Again the universality of elemental composition, integer and prime numbers, as well as an assumed understanding of the Hydrogen 21cm hyperfine transition by any culture capable of receiving the signal, was used to bridge the gap between cultures. However again, it can be asked just how culturally dependent the representation was. It is possible, for example, to imagine a civilisation with no grasp of binary notation, or indeed of discrete values, for which all things are seen to be on a continuum. In this case, the black and white (+ or -, 0 or 1) two dimensional, visual representation might make very little sense. Even on Earth there are also cultures in which human beings are not represented in visual media - for an alien culture with the same prejudice against representing living things, the visual representation of a human which might well be difficult or impossible to interpret, and may even be offensive.

It’s interesting to note that both the probe plaques and Arecibo message have also featured in science fiction.

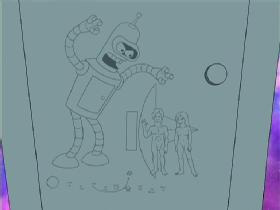

The Pioneer Plaques were notable for their graphic depiction of naked humans, which have appeared as visual cues in sources such as Futurama (“Godfellas”, 2002, see image to the left), Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (“Ardala Returns”, 1980) and The Outer Limits (“The Message”, 1995). However they’ve been somewhat superceded in science fiction by the golden disks that followed with the Voyager missions. Interestingly, at least two examples of the binary-encoded golden disks in science fiction have involved interactions with artificial intelligences:

One of the golden records was instrumental in the transformation of a hypothetical Voyager VI into the sentient V’ger in Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). Having encountered and interpreted the golden record carried by the probe, an alien race upgrades the damaged craft, imbues it with the knowledge on the disk, and sends it back to Earth, gathering data and sentience en route, until it inadvertently threatens the Federation in its search for its creator.

Another of the golden disks also features in the animated Transformers universe. This constantly-reinvented saga began in 1983 with cartoons based on a Japanese toy line, and has been revived and revised every few years since, with the launch of new toys, cartoons, comics, films or other media, often rewriting past continuity. In the Transformers: Beast Wars continuity, the golden disk (clearly recognisable as shown in the image to the right) was tampered with before launch; it carried additional coded instructions from the stranded series antagonist Megatron (an alien message piggybacking on a message to aliens!), which contributed to the return of Cybertronians to Earth in the series Beast Wars (1996-1998) and Beast Machines (1998-2000). Ironically for a device intended to facilitate communication, the disk itself became a powerful cultural artefact, the meaning encoded in it becoming largely irrelevant to its role in Cybertronian politics.

Another of the golden disks also features in the animated Transformers universe. This constantly-reinvented saga began in 1983 with cartoons based on a Japanese toy line, and has been revived and revised every few years since, with the launch of new toys, cartoons, comics, films or other media, often rewriting past continuity. In the Transformers: Beast Wars continuity, the golden disk (clearly recognisable as shown in the image to the right) was tampered with before launch; it carried additional coded instructions from the stranded series antagonist Megatron (an alien message piggybacking on a message to aliens!), which contributed to the return of Cybertronians to Earth in the series Beast Wars (1996-1998) and Beast Machines (1998-2000). Ironically for a device intended to facilitate communication, the disk itself became a powerful cultural artefact, the meaning encoded in it becoming largely irrelevant to its role in Cybertronian politics.

The Arecibo message, rather than the golden disks, was a central plot point in the 1984 BBC radio drama Space Force, written by Charles Chilton - who had experienced earlier popular success with Journey Into Space in the 1950s. In Space Force, radio signals of an apparently-alien origin to prove to incorporate elements of the Arecibo message, and to constitute a response to that message. In this instance, the aliens in question have already followed the signal back to the Solar System and encounter the crew of the eponymous spaceship near Jupiter. Curiously the information recognised as originating from the Arecibo contact attempts in the script (relating to the “great skinny triangle” of parallax and to “epsilon solar” or Jupiter) aren’t actually recognisable as appearing in the original Arecibo message at all. Nonetheless the scientific principles were sufficient to attract the attention of another species and to indicate the knowledge of the transmitting humans. It is fortunate for the characters that these aliens also come equipped with telepathic translation technology, which circumvents the necessary conceptual leap and steep learning curve to progress from scientific notation to conversation.

This last point is important: scientific diagrams and notation are excellent for conveying quantitative information and establishing a basic common knowledge. To go further, let alone establish meaningful conversation, much more extensive texts and much longer study are needed (as are available for future work in the university library in "Omnilingual"). For science fiction which involves routine communication with aliens, alternate methods have to be found.

In the Stargate universe, the original feature film (1994) and early episodes of Stargate: SG1 (1997-2007) show examples of a linguist, Daniel Jackson, identifying shifts in pronunciation and usage to become fluent (albeit usually unfeasibly quickly) in new dialects of known ancient languages which arise in displaced human populations. Notably, the 1997 season one episode “The Torment of Tantalus” shows Jackson discovering a multilingual inscription written in no fewer than four languages, and he begins work on decoding a fifth unknown ancient text using an electronic “book”. This begins with visual representations of elemental composition (including transuranic elements unknown to humanity). The dialogue discusses the idea that amongst cultures more advanced than the transplanted human settlements, science was indeed used as a universal language and comments on how similar the representation of atoms is to those humans use (although the visualisation is a bit odd, with very large atomic nuclei relative to the electron orbits, as shown in the image). However later episodes of the Stargate series jettisoned language difficulties in favour of simply showing both the displaced humans and aliens speaking modern English (except where plot demands required otherwise).

In the Stargate universe, the original feature film (1994) and early episodes of Stargate: SG1 (1997-2007) show examples of a linguist, Daniel Jackson, identifying shifts in pronunciation and usage to become fluent (albeit usually unfeasibly quickly) in new dialects of known ancient languages which arise in displaced human populations. Notably, the 1997 season one episode “The Torment of Tantalus” shows Jackson discovering a multilingual inscription written in no fewer than four languages, and he begins work on decoding a fifth unknown ancient text using an electronic “book”. This begins with visual representations of elemental composition (including transuranic elements unknown to humanity). The dialogue discusses the idea that amongst cultures more advanced than the transplanted human settlements, science was indeed used as a universal language and comments on how similar the representation of atoms is to those humans use (although the visualisation is a bit odd, with very large atomic nuclei relative to the electron orbits, as shown in the image). However later episodes of the Stargate series jettisoned language difficulties in favour of simply showing both the displaced humans and aliens speaking modern English (except where plot demands required otherwise).

This approach is fairly common in science fiction, and is occasionally explained in terms of some kind of rapid-learning translation technology. In the case of Doctor Who (1963 onwards), the technology is provided by the telepathic semi-sentience of the space-time craft TARDIS and so falls comfortably under the umbrella of Clarke’s Law [2]. Nonetheless, Mark Halley & Lynne Bowker contributed an essay to Doctor Who and Science (Harmes & Orthia, 2020) which discussed the feasibility of the device in the context of our current translation technologies, algorithms and linguistic theory, noting just how difficult this task is. Although regular grammatical structures may be straightforwardly identified given a sufficiently large body of text, this would likely constitute full libraries of content rather than a few words. Even then, the meaning of individual words, vocabulary, idiomatic or colloquial usage, homophones (sound-alike words) and cultural allusions would seriously compromise the ability of any system which can’t resort to telepathic interpretation of meaning.

Many of the same arguments apply equally to the Star Trek (1966 onwards) universe’s Universal Translator. This is a device that appears to be able to construct a complete, idiomatic mapping between languages on the basis of a handful of sentences, and without any form of bilingual text. It was established early on in the series (e.g. “Metamorphosis” 1967) that the translator analysed brain patterns to recognise meaning (i.e. was somewhat telepathic, or at least a remarkable remote-sensing medical device). Later entries in the franchise somewhat retconned this, and indeed the early development of algorithms for the translator was shown to arise from linguistic theory in the series Star Trek: Enterprise (2001-2005), which included a linguist in its main crew.

However this is also realistically a Clarke’s law situation, and it’s one which is perhaps harder to accept since it originates from a human culture and technology far closer to our own than that of the Time Lords. Despite this, given what we know about automatic translation by computer algorithms, the need for bilingual data and analysis text volume, the Universal Translator as shown in Star Trek is impossible, and best treated as a convenient narrative conceit (much like the transporter and the fact that alien species all seem to recognise the same “up” direction in space).

Interestingly though, Star Trek has not been oblivious to the importance of bilingual or omnilingual common-ground in communication. In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “Darmok” (1991), a species’ language is based entirely on metaphor [3] and proves incompatible with the Universal Translator. As a result, only shared experience between Captain Picard and an alien captain can provide contextual information necessary for mutual understanding. In another ST:TNG episode “Night Terrors” (1991), we return to the idea that science can provide that universal language in the absence of shared experience. The Enterprise encounters a space-time rift and a telepathic crew member receives a recurrent message which her mind interprets as “one moon circles”. As will likely not be a surprise by now, the crew’s escape from peril depends on recognition of this phrase as a description of atomic structure, and a request for urgently needed material. Hence even in a world of universal translation, science returns to the fore as a universal language.

How realistic is this? Scientists are increasingly recognising the unspoken cultural assumptions implicit in our formulation and description of universal physical laws. Even amongst human cultures there are significant differences in the ways number and other concepts are understood or visualised. Indeed, it’s been suggested that considering the issue of communications with aliens in this way may improve our understanding of those assumptions in our own sciences. Others have questioned the entire premise that other species would prioritise the communication of science over aspects of the arts, humanities or social sciences. Nonetheless, mathematics, physics and chemistry likely still represent our best options for establishing a bilingual text of common knowledge with any hypothetical alien species. Whether that common recognition of scientific knowledge can truly lead to comprehension and understanding between sentient races remains to be seen.

“A Universal Language?”, Elizabeth Stanway, Cosmic Stories blog, 28th November 2021.

[1] "Omnilingual" (Piper 1957) is now out of copyright and available as a free ebook from Gutenberg.org [Back to text]

[2] Clarke’s Third Law: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. One of several principles laid out by Arthur C. Clarke in an essay about the future in the 1970s. [Back to text]

[3] It’s fair to say that this unlikely scenario causes linguists almost as many nightmares as the universal translator. If the language doesn’t have regular discrete terms for objects, occurrences and actions, how can “Shaka, When the Walls Fell” (i.e. failure) have any meaning? What is a wall? Or falling? Nonetheless, the fact remains that all language is full of historical and cultural allusion - for example announcing that you plan “to boycott that sandwich shop” contains two words which are derived from proper names and whose meaning could not be inferred from their etymological roots or easily inferred from most contexts. “Darmok” has generated a remarkable number of academic papers and studies in areas ranging from psychology to information science. If you’re interested, there’s a long and detailed essay on this episode in The Atlantic, and an interesting article on using it to train machine learning on arXiv. [Back to text]