NHS means more than 'free healthcare'

The way ahead is realising the NHS means more than ‘free healthcare’.

Professor Roberta Bivins, Department of History, Warwick

In the wake of a global pandemic, there has rarely been a moment in history that the presence of the NHS in British life has been stronger. As we move forward from Covid, I think many more people understand how deeply embedded the NHS is in British culture - but also that this is not a neutral phenomenon.

As an historian of both medicine and migration in Britain, it is impossible for me to ignore the role of the National Health Service as a site where some of the most important cultural shifts of the late twentieth century took shape. And as a migrant from the medical wild west of the USA, I also love the NHS and what it stands for - for all its challenges, the NHS still feels a bit miraculous to me.

In this project, begun well before Covid-19, we wanted to find out what the NHS meant to its users and its workforce, but also whether it produced a different culture of health: was the NHS more, in other words, than just 'free healthcare' in the hearts and minds of British people? And if indeed it did produce strong emotions, what were they, and did they matter in terms of how people acted as well as what they believed about health and medicine?

The public were involved in our work from the very start, shaping not just our answers but the actual questions we asked. We wanted to move away from the top down history of the NHS, written from the perspective of Westminster and Whitehall to a history of the NHS that incorporated the people who made it what it is today: those who used it and worked in it, who wrote and attended plays and poems about it, who produced and watched NHS documentaries and films, and for whom it was a key part of their sense of themselves and their identities.

There was just SO much to explore! People cared so much about the NHS, and yet, many people didn't feel that their everyday experiences - even the negative ones - could possibly be 'historical'. After all, that is one of the fundamental features of the NHS: its 'everydayness.' Our investigations sometimes tested and challenged, which could feel awkward. But it’s not a history that can or should be hidden. There’s a case for arguing that a better understanding of the history of meaning, belief and feelings is important in helping the NHS continue to thrive - not just as a successful health service, but as an institution that unites an often otherwise highly divided nation.

This work wouldn’t have happened without the amazing team that my collaborator Professor Mathew Thomson and I were able to build in the Centre for the History of Medicine here at Warwick, and in the wider Department of History, or without the support of the University and the Wellcome Trust. It has been an incredible benefit to us to have at our fingertips the astonishing wealth of resources and expertise based in the University’s Modern Records Centre and in the Library's Sivanandan Collection, not to mention having the resources of Coventry and Birmingham right on our doorstep. The diversity of our communities in the Midlands really reflects the diversity of experiences and commitments people have in and make to the NHS.

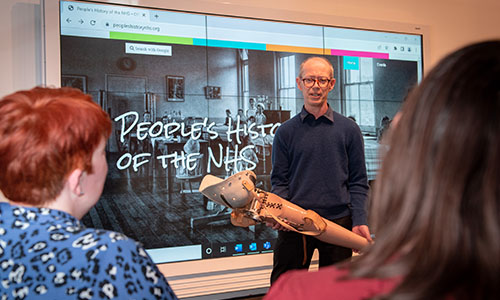

It has been incredibly exciting to reflect this diversity and complexity in some of the outcomes of our project, especially the BBC documentaries we produced or contributed to - ‘The NHS: A People’s History’ and ‘Our NHS: A Hidden History’ - in our Windrush Season and exhibition, our People’s History of the NHS website, and of course in our publications, all open access and free thanks to the Wellcome Trust.

history