Battle of Bread: The dock labourer

Conversations with unhired men after the morning's scramble for work - a consumptive ex-boxmaker from Camberwell, his old-school docker nemesis and an ex-con looking for a fresh start.

Published in The Railway Review, 6 August 1880 - read the original article through our digital collectionLink opens in a new window.

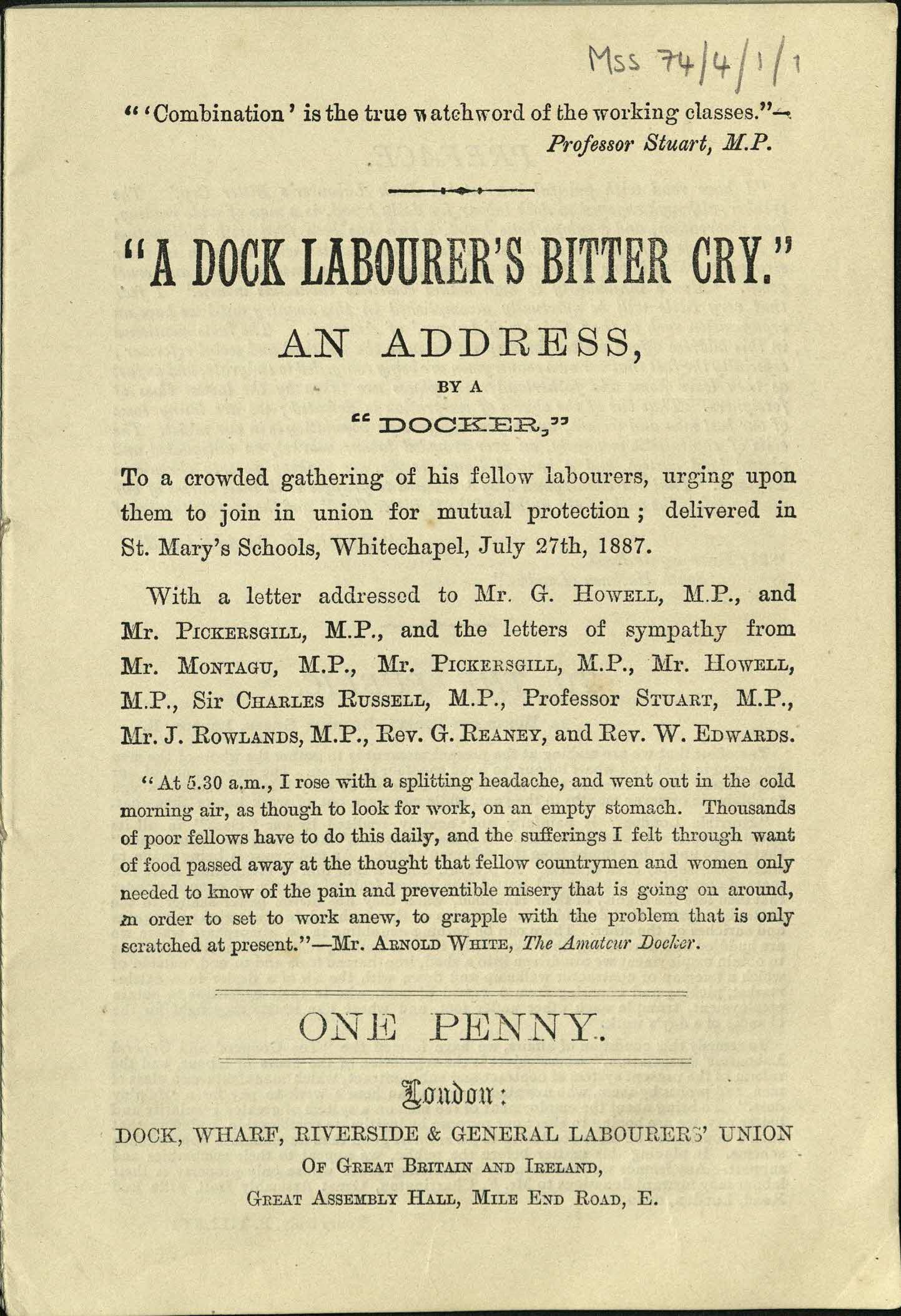

Illustration: page from 'A dock labourer's bitter cry', pamphlet by Ben Tillett, 1889, available online through our catalogueLink opens in a new window.

Every working day throughout the year, and between seven o'clock and half-past in the morning, there may be seen crossing London Bridge from the Surrey side a throng of pedestrians, who, judged by their dilapidated appearance, suggest a realisation of the prophecy embodied in the ancient nursery jingle commencing, "Hark, hark! the dogs do bark." Seemingly "the beggars are coming to town," rank and file, and at quick march.

A closer inspection, however, will speedily dissipate the idea. Ragged these are, poverty-stricken, and hungry-looking; but they have not the bearing of beggars, or their aimless, halting gait. A motley crew, if ever there was one; and one and all they are hurriedly tramping in the same direction — over the bridge, and down the bridge steps, and up Thames-street, and past Billingsgate, for that is the way to the London Docks, and that is their destination; while unless they are there before eight o'clock it is all over with their chance of being "took on" for the day, though they may, failing that, and if they have patience enough to wait, obtain in the course of the day an hour's work, perhaps two, and earn tenpence.

It must not be supposed, however, that these poor workers from the Surrey side of the Thames are the only ones who at that same time are making their way towards the London Docks. Those who have been described as hurrying across the bridge do not reckon more than three or four hundred probably; and it is barely a third of the number that every morning turn their faces eastward on the same errand. By a quarter to eight you find them crowded about the dockyard gates, the earlier arrivals sticking to their points of vantage, and, if need be, fighting to retain them as obstinately as gallery playgoers who besiege the theatre door on the first night of the pantomime. The crowd extends across the road to the opposite pavement, and surges into the adjacent streets like no other crowd that was ever seen. At eight o'clock the bell rings, and the hungry army being then free to enter, it rushes pell-mell into the great square that opens on to the river. At that side a chain is stretched across guarded by policemen, and the hiring foremen take their stand. It is not much use being early at the outside gate in hopes of figuring in the front row at the chain unless a man is a fleet runner, and can keep well ahead of those whose determination to be foremost, by hook or by crook, is backed by shoulders of breadth and a pair of sledgehammer fists.

All are in, and then ensues a spectacle that, once witnessed, is not likely to be soon forgotten. The number of labourers required is ever uncertain. There may be a hundred ships in dock waiting to be emptied, and there may not be a score. It all depends on the wind. There are sure, however, to be at least three times as many applicants as under the most favourable conditions can possibly be set to work; and this being the case, it is every man's endeavour to make himself as conspicuous as possible to attract the notice of the hirers who survey the struggling mob.

As soon as the foremen appear, a hideous uproar begins, and voices, accompanied with a kind of dance exactly suited to such music. The object is to catch the foreman's eye, or, failing that, his ear. "I’m here, sir!" "I'm Baker, sir!" "Mick Halloran, your honour!" "Hi, hi, hi! Good luck to ye, don’t forget Jerry Sullivan." "Do please, mister, it's old Sam, sir." "Patsy Green; Patsy Green!" and a thousand other frantic ejaculations and reminders, jerked out short and sharp like the barking of dogs; the strong ones leaping up and sustaining themselves there by resting their hands on their neighbours' heads or shoulders, and all waving their arms and hands, and sometimes their old caps, scrambling and jumping, so as to bring their faces in view of the foreman, though but for a moment. Eager are all faces, white with excitement, now that the critical moment had come, and so painfully beseeching is their expression, it seems impossible that all they are begging so hard for is the privilege of working for a few hours harder than scavengers' or bricklayers' labourers, and that for less pay than would satisfy a modern charwoman. They begged in vain, however, at least two-thirds of their number.

The hiring ceased, the fortunate few received their tickets and passed through, while the luckless majority, many of whom had journeyed probably four or six miles breakfastless through the nipping morning air, came slowly away, wiping from their poor chopfallen faces the perspiration the fight had cost them, and looking, many of them, as haggard and tired as though they had done a hard day's work.

"You don't appear well adapted for this sort of work," I remarked to one as he came panting out of the hot crush, and vainly felt to button up his tattered jacket with buttons that had been wrenched away in the fierce scuffle. "Well, sir, it is a little harder than fancy box making," he replied, civilly; "and that's the trade I was brought up to; but a man can't afford to be particular when he's been out of work since five weeks before Christmas and got four young 'uns to feed. It was through illness I lost my last shop, and they wouldn't take me back when I got well, because, they said, I looked too weak to work. A parcel of rubbish, sir, as if looks have got all to do with it. I'm as right as a trivet, 'cept for a bit of a cough that's troublesome of nights. That's the want of plenty of good grub; that's what's the matter with me. I'd soon show 'em about consumption if I had about a pound of good steak to sit down to every day. Did they say it was consumption that was the matter with me? Yes, they said it; but they're wrong. Could a man with consumption holler as loud as I can?" he asked with brightening eyes, and with a pink flush mounting to his just now quite white face. "Did you hear me hollerin'?" "I am sorry anyhow that you did so to no purpose." "I'm sorry too," the poor follow replied ruefully; "it's a long way to walk from Camberwell. Have I ever got a day's work here? Oh, yes, I reckon I've had about eight days' work, put the odd hours together as well, and that's in five weeks. No, it isn't much, but I couldn't stand it every day, even if I had the chance. It isn't so much the hard work, though they keep you to it awfully tight — it's the want of fairness of the old hands, and the rough lot who think it a lark to play tricks on a man who looks a bit delicate. They're as strong as horses themselves, but they're rare shirkers of work when they find the chance. That's what I mean when I say they're not fair. If you're working in gang at pulling and hauling altogether, they'll just lay their hands on the winch, and let them that's strange and new to the work take all the strain, and they're ten times worse if you show you're bit decent, and don't want anything to say to 'em. There's ways among 'em that ain't much to mention, but by which they can torment a man's life out of him a'most. It's done to drive strangers away. They call themselves the regular hands, and if there wasn't such a swarm of outsiders come every morning, they would, of course, do better. A man that's ever been respectable must swallow a lot to keep peace with 'em. It's worth while, of course, when a fellow is real hard up, as I am. Three-and-fourpence is a tidy sum to carry home. Say you spend the odd fourpence in victuals during the day, and have three shillings left — the rent and sixpence over. But that is a full day, and I don't care for days. They shake me all to bits. No; I'm not going back to Camberwell yet. Perhaps I shall get a couple of hours at twelve o'clock to two, and tenpence puts things a little bit comfortable home."

The trifle I pressed on the consumptive box-maker's acceptance would have passed unnoticed, but in his shamefaced bungling way of taking it the coin dropped with a sounding chink on the stones, attracting the attention of a man of altogether different breed from him I had been talking with — an enormous fellow, whose shoulders appeared in dingy white patches through the holes in his tattered old woollen "guernsey," and whose fustian inexpressibles were encircled at the waist by a leather strap stout enough for horse harness. He was sucking at a black short pipe, the stem of which was a bare inch long - an economical arrangement which enabled him to take into his nose all the smoke emitted from his lips. He scowled contemptuously at the fancy-box maker. "Ah, that's what a blooming barber's clerk, like he is, is fit for, mister," he remarked. "If he's a cadger, why don't he own to it open, and not come spilin' a man's day's work?" I replied that he had cadged nothing of me; that I was sorry to see one who was so weak and ill driven to seek a job there.

"But," said I, "I’ve no doubt you great strong fellows make the work lighter for those who are not so well able to do it." He grinned derisively. "Lighter for 'em! What for? What the blazes do they come here for if they aint ekal to the work?" "But I should have thought that if one or two of the little men who haven't much strength got with a gang of you big men you might let them off easy." The grizzly-muzzled rascal was so tickled that he took the black pipe from his lips to laugh. "Let 'em off heasy, hay! Oh, yes, we do all that, mister. It stands to sense, don't it! I’d chuck 'em into the river if I had my way. What do they want here spilin' a man for? All sorts and sizes of 'em come a swarming here, and they get took on and we're kep' out; and there'd be a lot more of 'em if we didn't jollop 'em." "What do you mean by that?" "Why, physic 'em : work 'em so that a day or two of it sickens 'em, and they aint got no more life or strength left in 'em than an empty sack. How's it done? Oh, it's done easy enough, if they get along with old hands. If it's truck work let 'em do all the pulling and pushing, and all the time bully and curse and swear at 'em for shirking their work. Same if it's crank work; and if it's backing loads, bustle 'em, tread on their heels, let things slip on 'em. That's how we serve the genteel uns, and them that aint got any strength, but want to make up for it by showing willing. Make it hot for 'em, and give 'em a bellyful. That's how to choke 'em off. Do I think it's fair to serve 'em so? Course I do. Oh, it's all very well to talk about poor fellows and havin' pity on 'em; what pity do they have on us? There's two ends to the stick, don't you know, mister. There's a job got to be done, and say it's a six-handed job. Well, the foremen know to a ounce what a six-handed job is, and how long it should take when what I call men tackle it. But s'pose three of the six are of the soft and slack-backed sort, like him what fiddled you out of that shillin', where's the fairness, then? It's we screw them and they screw us, and so, nat'rally, they get screwed."

I found amongst those who were turned away, and who still lingered about, lolling against the dockyard wall, or sitting in rows along the edge of the pavement in hopes of an hour or two's work "by-and-by," one or two whose opinions as regards dockyard casual labour were peculiar, and perhaps worth recording. It never occurred to me, for instance, to regard that vast refuge for the destitute in the light of a reformatory — a sort of moral furnace through which a man of tainted character might voluntarily transmit himself to be purged, and made fit to rank with honest men.

"I'll tell you, sir," the man remarked to me, "how it is that dock labour — hard as it is and poorly paid — has proved a blessing to a many who but for it would have gone on from bad to worse, until they got so deep there was no help for 'em. A man goes wrong; I know a man that did. Say, for argyment sake, that it was me, if you like. Say it was me that lost a good situation, where I was earning one pound twelve a week regular, by stealing something out of the shop I thought would never be missed. I had a nice home and a good wife and four little children, but I made the slip and got six months for it. When I came out I was like a lost sheep. Even my own brothers turned their backs on me; my character was gone, and nobody stuck to me but my wife. I am a watch-finisher by trade. After ten weeks of very near starving, I got a job at second hand, and when I took the work home the man I worked for was gone into the country, and wouldn't be home for a fortnight. Fancy being told that when we hadn't eat a morsel since the morning before, and were holding out on the strength of the good meal I was going to bring home with me! I couldn't stand it. My job came to two pounds odd, and I pawned one of the watches for fifteen shillings. Leastways, I tried to pawn it, but being ragged and hard-up-looking, the pawnbroker sent for a policeman on the sly while he was pretending to make out the ticket.

"The watch was a valuable one, and the other conviction being brought against me, I got three months. That broke me altogether. When I came out my wife, who was confined while I was in prison, had been took to the workhouse, along with the children, and the home was all gone. My character was gone, too, and my hands were so stiff and corned with the oakum and clinging hold of the handrail of the treadmill that I couldn't work at my trade even if I had the chance. Nobody knows, sir, what a torment to a man them prison corns are, or how they seem to be ever reminding him of what he has done and where he has been. But they had time to grow soft. Lord only knows how I lived for the next two months. I was either starving, or begging, or stealing, and I won't say any more than that I didn't starve, though I often come pretty close to it. My hands got soft, anyhow, which on account of my trade I was glad of; but I soon had reason to think differently. I was took up on suspicion, though, upon my soul, there was not a shadow of grounds for it. 'He is a convicted thief, your worship,' said the gaoler. 'That's true,' said I, 'but I have tried hard ever since to get a honest living.' 'Look at his hands, gaoler,' said the magistrate. 'They're as soft as a woman's, and his nails are too long to have seen much wear,' the gaoler replied. 'That's just what I expected,' the magistrate remarked; 'three months' hard labour as a rogue and vagabond.' And I did the three months devil-may-care and stubborn, and with no more thought about the future than a brute. It was a warder at Coldbath-fields who put me up to dock work. He was a young fellow, and about the best of the lot there. 'What do you mean to be up to when your time's out?' he asked me one day. 'Why not be a man and make a fresh start on the square?' 'That's easy said,' says I, 'but who'll give me honest work without a character?' 'I only know one place where they will give you work without asking questions,' says he, 'and that's at the docks. It's rough work, and it's small pay, but if a man's got it in his mind to go right, it's good enough to serve as a first step of the ladder he has slipped down from.' So I took that warder's advice, sir, and here I am, and here I've been casual labouring for the past seven months. It is terrible hard work for a man whose muscles aint very much, and who has been brought up to a soft-handed trade; the pay is barely bread and house-rent for a man with a family. It hasn't been more than nine shillings a week, take it all round. But the wife is a rare cheerful one, and she does a bit of work too when she can get it, and she's never the one to even give a hint about either the work'us or the prison, and so I mean to stick to the docks yet awhile. I've got one of the under foremen to promise that he'll keep his eye on me, and give me a good word if I have the good luck to come across a better place. Do I think that mine is a solitary instance? I’m sure it isn't. They are a rough lot here, sir — it stands to reason they can't be anything else — and all kinds of talk amongst 'em is free; and I know scores, if their words may be taken for it, who make no disguise of seeking work here, so as to 'wipe off the old score,' as they say, and make a fresh start. It is a stiff trial, sir, and it wants a lot of pluck and perseverance to carry it through; and no doubt a many get faint-hearted and fall back, through finding they can't earn enough at it to keep up strength enough to tackle the work. But I believe it is the means of lots of men turning about and making a new beginning."