Battle of Bread: Industrious dogs

Working dogs and their ways - "dog-taught" drovers' dogs, Punch and Judy performing dogs, begger dogs and 'Honest Bill', canine constable on the Blackfriars Road.

Published in The Railway Review, 27 August 1880 - read the original article through our digital collectionLink opens in a new window.

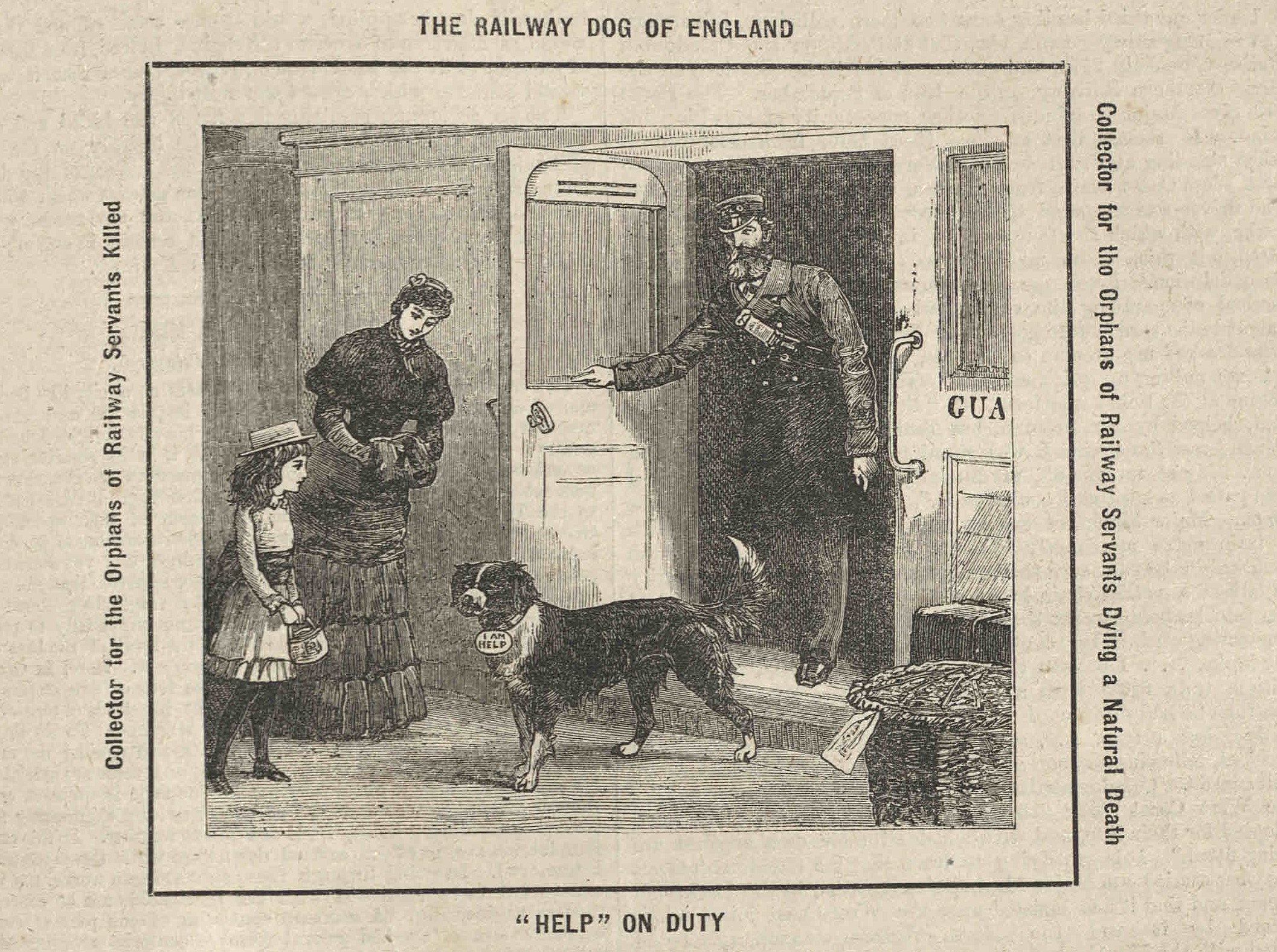

Illustration: engraving of 'Help', fundraising dog, included in 'The Railway Review', 26 October 1883.

Wishing to learn something concerning working dogs and their ways, I recently faced the horned perils of Copenhagen-fields on a market day, and engaged in conversation with a drover, as he sat resting after a job under the calf shed. I desired in the first place to obtain his opinion whether the breed still maintained its high character for shrewdness in sheep and bullock management. To all which he replied, after a little reflection — "If you want to know whether they are well up to the work expected of 'em, I answer yes; but if you ask are they as clever as they used to be, I answer no. Further, I answer, it can't be expected. There's nothing to cultivate and call out all a dog's abilities in these days, sir. It was in the old Smithfield times when the work that had to be done brought out all the talent a drover's dog had in him. When there was no laws and restrictions as regards the hours of the day when beasts and sheep might be took home from market, and when a man with his dog had to fight his way with his drove all amongst the horses' legs and the cart and wagon wheels, and that sometimes hours after it was dark. There was dogs in them times, sir, that could do any mortal thing but talk — talk English, I mean. They knowed every language that sheep and beasts talk — no matter what country they come from — and wouldn't stand no more nonsense from a Spaniard or a Dutchman than from a Devon or a Hereford. But it's different now; more orderly and better manners all around — beast, dogs, drovers, all the old kit. 'Pon my soul I think so. Why, heart alive, in my recollection it used to be regular Bedlam broke loose on market days, through all the streets of the City, and there wasn't a week but there was a few tossing cases brought before the magistrates."

"Then am I to understand," I remarked, "that any dog of ordinary intelligence is equal to all that is required of it as a drover's dog?"

"No, I won't go so far as that, sir. What made you ask?"

"Because, looking round from where we now stand, I can see dozens of dogs — and you may see them too — who are little better than street curs, judging from their appearance. If, as you would make out, the business is so exclusive, how did they find their way into it?"

My drover raised his ochrey cap with the end of his stick, and slowly scratched his head with the goad, as he replied—

"Ah, now you're on a subject that's miles beyond me and everybody else I ever talked with about it. How is it indeed? It's a pity they havn't got the gift of langwidge to tell us how it is. How is it that a marine, which p'rhaps his parents might have kept a fried-fish shop somewhere, grows up to be a admiral; or a Johnny Wopstraw, from the ploughtail, takes the Queen's shilling, and goes on dewelopin' something that was planted in him accidental, until he comes out one day all a blowin' and a growin' as a captain or a general? It's much about the same with these common-looking dogs that takes up with drovers' work. Nobody asks 'em to take it up. They feels, I suppose, that they've got the talent in 'em, and so they perseweres."

"But some one must teach them their duties?"

"Oh, they're dog-taught, of course."

"How do you mean, dog-taught?"

"I mean that the dogs teach one another. Where would you find a man who, even if he could converse with a dog like they do to each other, could put a animal up to all the hundreds of dodges and wrinkles and manoeuvring that a knowing old drover's dog is up to? When a man has a promising young dog of the right breed, he places it under an older one to learn the business. It is much the same with the mongrels, except that they find their own teachers. They follow the sheep or oxen at first whenever they see a chance, and do their best to make friends with the dog in charge until they pick up knowledge, and are after a bit reckoned by some drover as being worth their wittles, and so they are took on trial."

When my friend the drover spoke of the dogs of his craft as being the only "real workers" of the canine family, he overlooked two branches of doggish industry that certainly may fairly claim exemption from the imputation of idleness. These are the dogs through whose eyes blind men see, and the animals who earn their bread, if not by the sweat of their brow, by the fagging and fatigue consequent on their exertions as public performers. As far as may be judged, the canine creature whose life is devoted to guarding the person and property of a sightless master need not be of any one particular breed. The main essentials are that a candidate for the responsible situation must be a dog of sedate mien and past the age when it is liable to be tempted to abandon its helpless trust in a paroxysm of high spirits and go larking with vagabond curs, who may take a malicious delight in alluring him away. Neither must the blind man's dog be an animal of quick or irritable temper, nor too ready to resent the taunts and insults of rascally street boys, who, under pretence of having merely a bit of fun, may have larcenous designs on the tray the dog holds for the reception of charitable coppers. It is a curious feature in blind men's dogs that even amongst themselves there is nothing like trust and harmony. It may, perhaps, arise from their being so everlastingly exposed to the insolence of ill-bred puppies, who take a mean advantage of their helplessness while on duty, that their faith in their kind is shaken beyond recovery. Be that as it may, I only know that, being on one occasion present at an indigent blindfolks' tea meeting, the invited guests at which had for the most part brought their dogs with them, there was presently such a tremendous scrimmage under the table, to the legs of which they were tethered, that the meal had to be delayed while each separate owner parted his animal from the other combatants and kept him at his side with a short commons of chain.

As regards performing dogs, with the exception of those who are inseparable from Punch and Judy, and a few who, along with their masters, eke out a miserable existence by doing their best to dance on their hind legs to wretched attempts at music, together with some others who exhibit their talents by leaping through hoops and over each other's backs, this once numerous family seems to have vanished — from the streets, at all events. It by no means follows, however, that because Working Dogs of this class have had their day it betokens any falling off in the intelligence of the tribe generally. It would be a mistake to assume that trick dogs and those that appear as public performers are the most intelligent of their species. On the contrary, it would seem rather that canine creatures that submit to toil for a living in the way indicated are possessed of brains just enough to make them aware that, left to their own devices, they would be unable to hold their own in dogdom, and that with them it must be the paunch of slavery or no paunch at all. In the majority of cases performing dogs are of the poodle breed, and who ever saw or heard of one of spirit? It may be patient, meekly obedient to its teacher, and possessed of a retentive memory, but it evinces no pride in the profession to which its limited talent drives it. However clever it may become, however much applauded by an admiring audience, it seldom or never betokens by a twinkle of its eye, an involuntary bark, or even by an extra whisk of its absurdly-tufted tail, that it derives the least gratification from all the cheers and hand-clapping. It goes through its tasks with automaton-like serenity, and when it has done being funny to order, it resumes its four feet, and with a puckered mouth and a dejected eye, returns to the melancholy reflections from which it was roused when the exhibition commenced. It may be argued against this that no one ever yet saw a poodle in a Punch and Judy show, and likewise that, time out of mind, "Tobys" have been notorious as ranking amongst the most knowing of their tribe. My respect for Toby prompts me to endorse every word that can be said in his favour, but I altogether demur to the insinuation that the canine actor attached to Mr. Punch's theatre is to be classed as on a par with the performing poodle race. Toby has his part to go through, and his intelligence tells him that stage discipline will not permit him to deviate from the lines set down for him; but who will make bold to say that he ever saw a Toby in his part who did not, in every snarl and curl of the lip, in every glare of the eye and erection of the tail, unmistakably demonstrate his utter contempt and detestation for the head-cracking old ruffian with the hump, and his readiness to bite him. It is all very well to say that Toby has no feeling or opinion in the matter, and that he would just as soon bite the beadle, or Jack Ketch, or even the persecuted Judy, as Mr. Punch himself; but evidence to the contrary is furnished by the fact that he never does bite any one else, even by mistake, and that, when the moment arrives for him to take the shocking old wife-beater by the nose, he does so with an eagerness and a relish that rasps the red paint of the chuckling tyrant's proboscis, afterwards licking his lips as though it were the despised enemy's blood.

A poodle could no more play the sturdy and thoroughly English part of Toby than the last-mentioned gifted animal could or would condescend to dance on its hind legs or leap through hoops for a living. Were an Act of Parliament for abolishing Punch and Judy put in operation to-morrow, and all the Tobys in London thereby thrown out of employment, it might safely be wagered that not one would find its way to the Home for Lost and Starving Dogs at Battersea. Toby could pick up a living anywhere, and almost as well without a master as with one. It is not every dog, however, who, having neither home nor master, is dependent on his own exertions for a livelihood, who can claim to be a "Working" Dog in the sense in which the term is generally understood. They may be industrious, but they are very far from honest. Some are arrant thieves — habitual criminals — who prowl about dogs'-meat shops with as deliberate an intent as that which actuated Master Noah Claypole of practising the "kinchin lay," which, rendered into English, means robbing little children. The latter are sent for the skewered ha'porths and pen'orths for the cat or dog at home, but a threatening snarl and a sudden snatch does the business, and the mean robber is off with his prize. Then there are scheming dogs who, domestically speaking, are peculiarly circumstanced. They have a master and a home that is all that can be desired, excepting that there is little or nothing to eat. It is within the scope of canine sagacity, however, to surmount this obstacle to perfect content and happiness without much disgrace or degradation. As hundreds of working men could testify, there are coffee-shops and tap-rooms where they (the labouring classes) dine, which are punctually visited by a certain dog at dinner time, and at no other, the object being, of course, to solicit scraps of meat or bones to pick. Such dogs are known to have their regular round, and to make straight for home again as soon as they have accomplished it. Again there are beggar dogs, who acquit themselves as cadgers so cleverly that they must have learnt the art of two-legged professionals. Though the beggar dog is a well-fed villain, he has the cunning to assume, when it is necessary, a woebegone expression of countenance, and his simulation of a half-starved shiver is nothing short of perfection. He haunts respectable and quiet neighbourhoods, with a shrewd glance through area railings for anything in the shape of feeding that may be going on in the kitchen, and there he makes his stand. He looks so inexpressibly wretched, and whines so dejectedly, that hard indeed must be the heart of cook or maid-of-all-work who could deny him the plate gleanings.

It is a fact not generally known that there are hundreds of dogs in the metropolis (with a little of the Toby blood in their veins probably) who lead prosperous and protracted lives, banned though they be by the law that denies their right to live at all, inasmuch as they pay no dog tax. I was once introduced to an animal of this kind — a Working Dog — the scene of whose useful labours was a market street in the neighbourhood of the Blackfriars-road, and, though then scarcely in the prime of life, he had earned for himself the honourable sobriquet of "Honest Bill;" a distinction which sat more gracefully on him because, judging from appearances, of all dogs unlikely to try, even by way of amusing experiment, the ways of honesty, Bill seemed the most unlikely — a bobtailed, crop-eared brute, with a mottled mark crossing the bridge of his nose, a thickening at his cheek bone, as though he were slowly recovering from two bad black eyes, and a sinister curve of the left-hand corner of his mouth that showed some of his teeth in an unpleasantly suggestive way. Having been run over in his puppyhood, Bill was lame of a leg, and altogether, to look at, as unpromising a canine vagabond as ever picked up a larcenous living. It spoke volumes for Bill's moral courage that he had contrived to live down popular prejudice begot of his uncanny aspect, and secured for himself a fair trial on his merits. Not that he was desirous of attaching himself to any one master. Perhaps he had tried it, and in vain, so often in his younger days, and had been so persistently kicked out of doors, that he at length grew too disgusted to try any more.

When I had the pleasure of being introduced to Honest Bill he was engaged in the performance of his self-imposed duty as a canine constable. There were several butchers and cheesemongers' shops in the street whose tempting displays were a sore temptation to the prowling curs of the neighbourhood. It was Bill's business to keep a sharp eye on these marauders, and to lie in ambush for their detection and discomfiture. He would lurk in the least suspected places, and from thence sweep down on a four-footed thief with a degree of savage ferocity that made the delinquent glad to drop the steak or rasher he had purloined and run for his life. If he did not run, Bill was quite prepared to fight it out on the spot; and few dogs who thus rashly risked the ordeal of battle were ever seen again in that neighbourhood. As for Bill himself, there were a score of credible witnesses ready to attest that he was never known to steal so much as a bone or a bacon-rind. When he required anything to eat he would ask for it in the unmistakable way dogs have of doing so; and that he was seldom refused was evident from his sleekness and plumpness. Though he would accept food for his services, he would be beholden to no man for a lodging. While a single shop remained open Bill was to be found on his beat; but as soon as the shutters were put up he vanished, no one knew where, though, judging from his trim and cheerful appearance early next morning, no doubt wherever they were, Bill's lodgings were respectable, and such as no honest dog need be ashamed of.