How the Sabbath's kept in the heart of the city

The City rag-fair, the Duke’s Place gold and silver fair, and Sunday drinking.

Published in The Railway Review, 20 August 1880 - read the original article through our digital collectionLink opens in a new window.

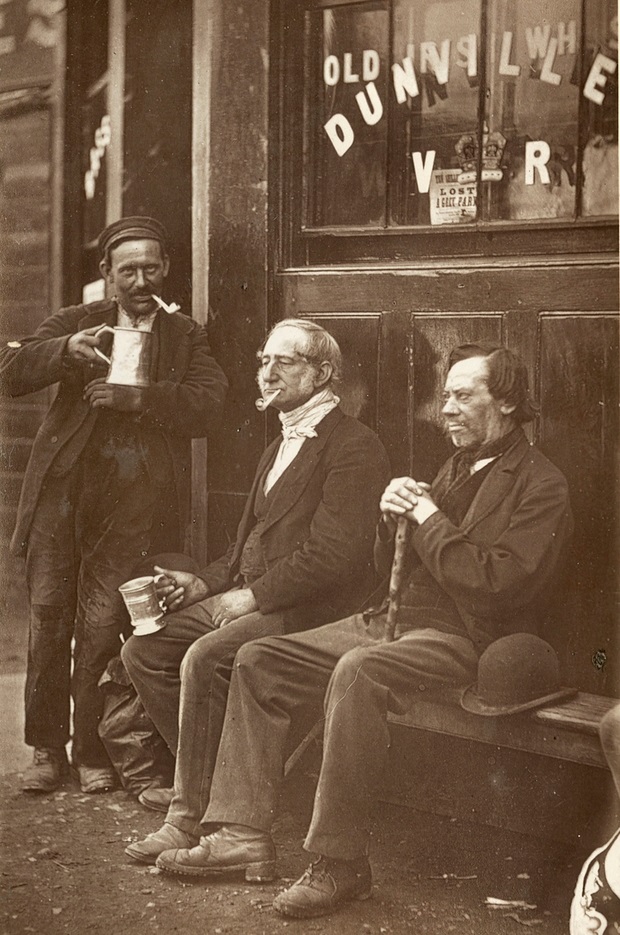

Illustration: "The wall worker", from 'Street Life in London', 1877, by John Thomson and Adolphe Smith, available through the LSE Digital LibraryLink opens in a new window.

Rag-fair has been held in the centre of the City of London on the Sabbath morning time out of mind, and still flourishes there. The fair is situated between Bishopsgate and Whitechapel, and though the operations under the Metropolitan Improvement Act have curtailed its dimensions, it has not in the least diminished its attractions. The crowd begins to collect just at the hour when the first chimes in the belfries of the City churches commence to call good folks to prayer.

Swarming from the north, from the south, from the east, three abreast on the City pavement, with their short pipes and their foul language, tattered as beggars, most of them, and all of them as dirty. Space in the fair for the vendors of made-up makeshifts in the shape of male and female wearing apparel is very precious. The muddy pavements of the lanes and the alleys and the open square must be quite a Tom-Tiddler's ground, judging from the shrewd care with which the collectors and their men go from stall to stall to measure the occupied ground to an inch. Scores of the sellers have no stalls, but carry their goods about with them, wriggling and squeezing through the malodorous mob, laden with old coats and trousers, and wearing ponderous necklaces of boots and shoes threaded on a string, while peripatetic hatters bear their fragile ware harmless through the press by adopting the ingenious device of hanging the hats in the interior of an expanded umbrella and elevating it aloft. In heaps, in odd corners, may be seen almost any quantity of unwholesome-looking bedclothes — blankets, rugs, and sheets. And in the midst of the crushing and tramping and the blasphemous bargaining — and the never-to-be-forgotten sickening smell — hot soup is vended out of tin cans, and stewed eels, and fried fish, and pickled olives, and whole cucumbers, which the mob handle rough-handed, and take a refreshing bite at alternately with whiffs at their short pipes.

That is how the Sabbath day is observed in one part of the City. Now let us escape from the sweltering crush into comparatively sweet-smelling Houndsditch, cross over to Duke-street, and thence to a square called Duke’s-place, and where, for purposes of legitimate trade, orange and nut merchants do congregate. But the trade done here on Sunday morning is not all of a legitimate kind. It is not generally known — but it is none the less a fact — that the law which prohibits the sale of intoxicating liquors on a Sunday morning is inoperative in this neighbourhood. There are three public-houses within fifty yards of each other, and at each of them, during morning church time, not a rag-fair but a gold and silver fair is held. In one of the places the business done is of a marvellously free-and-easy kind. There is a sale-room and stalls, but the chief of the trade seems to be done by persons who carry rings and chains, like loose change, in their trousers pockets, and who produce watches in a bunch, and parcels of earrings and brooches from mysterious receptacles in the bosoms of their waistcoats.

There are no difficulties as regards admittance at these public-houses. The doors stand ajar. The customer goes in, and there, at the end of the passage, finds a liquor bar, calls for what he fancies, and is served without a question.

In a spacious room, arranged on tables, are literally heaps of gold goods and silver goods and unset precious stones, and the space between the tables is crowded with lookers-on and buyers, who smoke cigars, befogging the chamber so that it is not easy to see the length of it. There is honour amongst these jewellery-mart habitués, however, and it is, of course, all right; but supposing a hundred or so of the roaring roughs of the rag-fair on the opposite side of the road got wind of the prize! They are not withheld by moral scruples; all that is required is some untoward event to rouse their ferocity, or to tickle them to an extra display of playfulness, and five hundred strong, and with their leaders well primed with fiery liquor, to be so freely obtained during church time in the immediate neighbourhood, they could almost with impunity make a raid on all the adjacent churches, and pillage the terror-stricken congregation before the police of the City could muster in sufficient force to scare them.