An introduction to Crossman’s philosophy: ‘virtue’ and ‘vice’

Richard Crossman’s mind was far from compartmentalised; something which the sheer breadth of the collection at the Modern Records Centre demonstrates. His ideas from one arena of life could be, and often were, interchangeable with those in another. This mutual interchangeability expressed itself in his understanding of the world and in his use of certain terms or turns of phrase to evoke it.

One of the chronologically earliest documents held in the collection is an essay in Crossman’s handwriting entitled, simply, ‘English essay’.1 The text itself treats the question of enthusiasm as virtue and vice; in particular, the relationship between idealism and individualism and their concurrent role in the production of art and aesthetic. It is undated, but was probably written while he was at New College. Whether or not the essay was ever submitted as a piece of university work is not clear, nor is there any available record of what mark it might have achieved.

As a Classicist and a philosopher, this questioning of the thin line between virtue and vice and good and evil recur frequently in his phenomenal output. When he describes Nazi Germany, for example, he argues that the Nazi vision of humanity is comparable to Milton’s depiction of Satan in Paradise Lost. Both have, initially, much to recommend them – courage and loyalty being two principal elements – but that because they lack the ‘one virtue’ of sympathy or compassion, ‘all these virtues become vices’ which are irredeemable.2

When any consideration is made of Crossman’s anti-totalitarian beliefs, it is easy to ignore or to forget that his is a deep-rooted, philosophical opposition, rather than the sort of irrational paranoia which drove the McCarthy witch-hunts. Crossman is more aware than many within political parties of the dangers posed by doctrine and the fanaticism which can easily turn it into dogma. Political ideologies are all, he argues, ‘virtuous’ in some way otherwise they would not appeal; but he urges his audience to consider the ‘vices’ which accompany them, and which ultimately flow from them, in order to obtain a true, wholesome picture of what risks a specific ideology might pose.

Crossman and democracy

As a man whose training was in Classics and academic philosophy, Crossman undoubtedly took more of an ‘intellectual’ approach to political problems than many of the people who were to become his colleagues. For example, during the 1940s he was to lament that no great work on democratic socialism had been published in Britain for over a decade; and despite the best efforts of Hugh Dalton to console him (by pointing out that the dearth of good socialist literature was due to the fact that ‘all who could best write it’ were currently engaged in government)3 he remained convinced that socialism was being done a grave disservice.4

It would be disingenuous to suggest that this makes Crossman more of a ‘thinker’ and less of a ‘doer’, but he did nevertheless enjoy having long rationales worked out for nearly everything and was a fierce disputant with his colleagues both inside and outside of the cabinet.5 As Tam Dalyell asserts, Crossman wanted to provide democracy with a new basis and rationale which could withstand scrutiny.6

Yet, as the student of Plato that Crossman was, he could not help but conceive of democracy’s difficulty in Platonic terms. Reflecting the long argument in Ancient Athens between democrats and aristocrats, Plato had sought, in the Republic, to envisage the perfect system of government. The Ancient Athenian definition of the two words was very different from their modern meaning: ‘Aristocracy’ derives from a word meaning ‘the rule of the best’ or ‘ the best qualified’ and it contrasted with ‘democracy’ which essentially means ‘rule by all free men’ (women and slaves being excluded). Plato argued that since all normal men were not intellectually gifted, they lacked the capacity to rule and would become corrupted by their own selfish interests. His solution was rule by an intellectual aristocracy of self-perpetuating ‘philosopher kings’ who, unlike other free citizens, would be denied property ownership rights and luxuries in order to ensure that their ideas were not ‘corrupted’ by democracy and mercantile capitalism.

That is why the Republic’s system of government is very difficult to classify in any modern understanding of left-wing or right-wing ideology, and why Crossman regarded him as the father of totalitarianism. By arguing that people should be ruled by those who know what is in their best interests, Plato implicitly accepts that individual opinions can and should be subordinated to the opinion of a ‘higher power’ and thus lays the foundation stone for justifications of Communism and Fascism. Another totalitarian element to Plato is his belief that the individual should be subordinated to the state and should, if the need arises, be prepared to give his life for it.

Given Plato’s objection to democracy, it is little wonder that Crossman saw education (the raising, as it were, of each individual’s ability to the point that he can think in the terms of a ‘philosopher king’) as the main tool towards realising democracy. Instead of rule by a closed community of philosophers (‘a chosen few’), he seems to propose that as many people as are able should be raised to that high standard. In a speech to the Coventry teachers’ association in December 1959, he asserted his belief that ‘the greatest problem we face [in educational terms] is homes where the mind scarcely operates, and therefore the mind has to be awakened in the school’.7 In the words of Tam Dalyell, Crossman genuinely believed that ‘it was realistic, not optimistic, to use education in order to substitute genuine social democracy for oligarchy’.8

Intellectual democracy, he appears to suggest, must come before political democracy – and one of his proudest achievements in this regard was undoubtedly Plato Today, which had proved popular both with academic philosophers and laymen. In the period prior to the 1964 election, Crossman began to take an interest in Scandinavian politics – in particular, the success of the Swedish social democrats. They appear to have become a vision of the type of democratic and socialist society that Crossman hoped could be created. ‘Here is one country’ he told audiences on the Hebrew Service, ‘where the kind of socialist ideals in which the British Labour Party, the British trade unions and the British co-operative societies all believe, have been realised by practical politicians in the life of a modern community’.9

Crossman and totalitarianism

Crossman’s opposition to totalitarian doctrines is driven by more than simplified paranoia of the kind which produced the McCarthy witch-hunts in the United States; it is, by its very nature, an intellectual and philosophical one. In Plato Today, Crossman effectively lampoons both Fascism and Communism through the prism of Plato’s logic (his memorable chapter on Plato and Fascism is written in the form of a letter from Plato to ‘his friend’ Aristotle, in which he is ‘anxious to pose’ a problem arising from ‘my journey back to the world of space and time’)10 and in the process serving to subvert and critique both Plato’s ideas and Fascism.

Communism fared little better:

Plato would feel only disgust for the Communist glorification of material and technological advance. The worship of machine power and natural science would seem to him merely vulgar, and he would laugh at the self-complacency with which Russia asserts that she is outstripping her capitalist rivals.11

Indeed, Crossman considered both merely as two sides of the same evil. In a broadcast to mark May Day in 1940 he contrasted what he termed the ‘three rival ideas’ which were by that stage being expressed in May Day demonstrations: ‘the communist idea of the proletarian dictatorship, the Nazi idea of the racial dictatorship, and our democratic idea of the free Labour Movement.’12 The first two of those ideas, he asserted, led only to militarism and barbarism, only the final one offered humanity any sort of hope.

Presidential Prime Ministers and the Cabinet

No sooner had he left frontbench politics after the 1970 general election, Crossman seemed to turn almost immediately to an examination of the role of the British government and the unconsolidated constitution under which it operates. Of course, as with most of these interventions, Crossman’s interest was hardly sudden; he had written an introduction for a new edition of Walter Bagehot’s English Constitution,13 and his diaries record more than simply a passing interest in the mechanisms of government.

In Plato Today he had included a chapter entitled ‘Plato Looks at British Democracy’ in which he argued that Plato would find modern British democracy very different from the system of Ancient Athens, and, indeed, would probably not recognise it as a democracy at all.14 Likewise, in a radio talk from 1963, he warned against the modern trend of divesting politics of its responsibilities.

In 1970 he was able to return to the question of prime ministerial government which he had been required to side-track over the course of the last seven years. He appeared as an interviewee for a BBC programme in which he asserted that power was being removed from the committee system of the cabinet and becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of the prime minister (an argument made most forcefully in his treatise, The Myth of Cabinet Government, published in 1972). He even, recalls Dalyell, regarded Harold Wilson’s government as having absolutist ‘elements’.15

His opinion on these matters, however, was slow to evolve. In the early stages of his dictated diary (Sunday 22nd November 1964) he was certainly more favourable to what Wilson was trying to do – at least initially. The cabinet, he said, had been divided by ‘ two tremendous arguments’ over pensions and the content of the budget; yet, crucially, ‘in each case … the PM failed to get his way.’16 At least initially, Crossman regarded Wilson favourably, as a leader prepared to devolve political responsibility and listen to the wishes of his cabinet:

Now, I can’t now say that Harold is a presidential prime minister, on the contrary he has done what he said he would do, delegated genuinely so that each cabinet minister can run his own cabinet ministry without running to him for assistance. As long as I carry on satisfactorily and don’t cause trouble, he’ll be satisfied with me.17

Yet that particular episode was recorded during the government’s honeymoon period, and the diaries also preserve examples of ‘Prime Ministerial Government’ in action. On Monday 29th May 1966 (when Crossman was Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Commons), he recalled reading minutes from a Cabinet committee in which there had been a disagreement about British aid to Israel between Harold Wilson and George Brown, on one hand, and Jim Callaghan, Barbara Castle and Roy Jenkins on the other. Crossman noted that:

the discussion was passionate and extremely stirring yet when it had been boiled down and dehydrated by the Cabinet Secretary very little of it remained. In fact the account which they had circulated was trimmed down to suit the conclusions the PM wanted to have recorded.18

However, the complexity and transience of these episodes of Prime Ministerial interference are exemplified by an item in the diary from the following day, when Crossman noted a ‘case where Prime Ministerial government certainly didn’t work’ and Wilson was forced by the cabinet to alter his policy on Israel.19

Crossman and religion

One institution which demonstrated Crossman’s theory of ‘virtue and vice’ was the Church, but even here the picture that emerges is complex and sometimes contradictory. According to Dalyell, Crossman had always been a humanist (at least for as long as he had enjoyed a professional relationship with him) yet had a Christian funeral service after his death.20 Indeed, his relations with the Church might well have been described as cordial. He regarded ‘Christian Socialism’ as a vital force in the development of modern British social democracy and once argued that ‘abolishing’ the profit-motive ‘is a job for the Churches’ rather than politicians.21

However, his associations with Christianity appear to go back much earlier. His mother has been described as an ‘Anglo-Catholic’, and Crossman requested to be confirmed within her Church at the age of eleven. He once told Dalyell that he did not take his mother’s religion seriously, but did take an almost perverse and childish delight in confessing his sins to the priest.22 Then, while at Winchester (which had acquired a liberal and modernist reputation), he read D. H. Lawrence and, in Dalyell’s words, promptly ‘denounced Christianity as humbug’.23

This did not, however, preclude Crossman from having sympathies with the religious and their ideas. In his early broadcasts about Nazi Germany, he seemed to express solidarity with the Church and its treatment by the Nazi state; setting Christian ‘virtue’ against the Fascist ‘vice’. Similarly, Crossman’s political development was profoundly influenced by that of the American commentator and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Both men were united in their belief that democracy was a necessary form of government to prevent humanity descending into tyranny; yet even here, according to Dalyell, Crossman refused to accept the Christian basis to Niebuhr’s arguments.24

The strange relationship to religion can even be found in his ‘English essay’, where he seeks simultaneously to praise and censure Christianity. The essay deals with the question of what is meant by the term ‘enthusiasm’. Christianity took its meaning from the word’s Greek root; a literal ‘filling’ of an individual with the force of the Holy Spirit: ‘The Christian … believed he was filled with God, and it was this enthusiasm, he declared, which was the driving power and motive energy of his life.’25 Crossman appears to have seen religion in the same terms as politics; with the capacity for good and evil (‘virtue’ and ‘vice’) not only co-existing in the same space but deriving from the same source.

As would be the case with Nazism many years later, the ‘vice’ is the cumulative effect of a single, undermining flaw which undoes the virtue (or raises it, through misdirected enthusiasm, to the level of fanaticism). ‘A man, a whole nation’ he warned:

can be and often is carried away by enthusiasm wrong or misguided […] If we look at one side of history of Christianity we see a ghastly roll of mistakes, the Inquisition in Spain and Holland, the massacre of the Huguenots in France, the persecution of the Puritans … Nearly all the men who committed these excesses were sincere and up to their own lights virtuous.26

He concluded with a more optimistic view of Christianity, which may well have befitted his youthful attitude. It was something, he felt, with which he could co-exist, and which would complement the objectives of democratic socialism:

Christianity, for all its mistakes, is the only cause of the increase of purity, humanity and international unselfishness. The League of Nations is a living proof of the work of Christian enthusiasm, and, whether it is a success or not, its very foundation is enough to justify Christianity. Though Christians have erred, yet it is Christians that have given Europe its pushes forward, until today we can claim that the doctrine of love is at any rate recognised universally as the ideal for social if not political life.27

Andrew Burchell, August 2012

References:

1. MSS.154/3/AU/1/15-19.

2. MSS.154/4/BR/1/112-119.

3. MSS.154/3/AU/1/278.

4. MSS.154/3/AU/1/278 and Tam Dalyell, Dick Crossman: a portrait (London, 1989) p. 23.

5. Ibid, pp. 4, 17.

6. Ibid, p. 27.

7. Coventry Evening Telegraph, 4 December 1959, (MSS.154/10/4).

8. Dalyell, Dick Crossman, p. 31.

9. MSS.154/4/BR/10/226.

10. R. H. S. Crossman, Plato Today (London, 1959, second edition) p. 144.

11. Ibid, p. 132.

12. MSS.154/4/BR/1/104.

13. A copy of this is contained in MSS.154/4/BAG/1.

14. Crossman, Plato Today, pp. 86-98.

15. Dalyell, Dick Crossman, p. 27.

16. MSS.154/8/205b.

17. MSS.154/8/205b.

18. Volume 2, p. 356.

19. Volume 2, p. 358.

20. Dalyell, Dick Crossman, p. 26.

21. MSS.154/3/AU/1/221.

22. Dalyell, Dick Crossman, pp. 15-18.

23. Ibid, p. 17.

24. Ibid, pp. 26-27.

25. MSS.154/3/AU/1/16.

26. MSS.154/3/AU/1/18.

27. MSS.154/3/AU/1/18-19.

Illustrations:

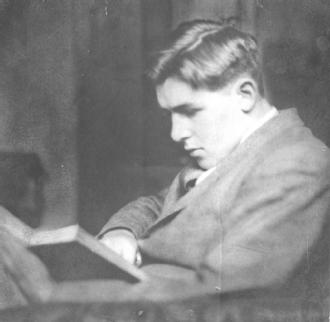

Photograph of a young Richard Crossman [in private collection]

Photograph of Wilson Cabinet [included in additional deposit of Crossman papers (accession 706)]