Space Sweepers

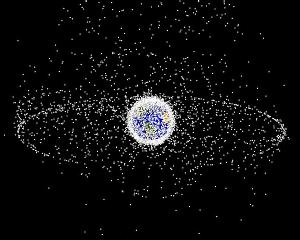

The threat to space travel presented by space junk - the debris left behind by earlier human activity - has long been recognised. At the speeds associated with Earth’s orbit, even a fleck of paint can strike an astronaut or space capsule with the force of a bullet. Naturally, science fiction has not failed to explore both the threat and the potential dangers of ignoring it.

Deadly Litter

Early space missions were relatively casual in allowing debris - in the form of either waste products or the rocket stages required for their take-offs - to be discarded in space. Space, after all, is big [1] and the human craft passing through it small, rendering the chance of collision with discarded objects similarly small. With increasing time and increasing usage of space, the risk of collisions between active craft and debris has increased, and the risk of untrackable small debris has been recognised. In just the last few years, both ESA’s Sentinel 1A earth-observation satellite and the International Space Station have been damaged by strikes from debris particles less than a centimetre in size.

Early space missions were relatively casual in allowing debris - in the form of either waste products or the rocket stages required for their take-offs - to be discarded in space. Space, after all, is big [1] and the human craft passing through it small, rendering the chance of collision with discarded objects similarly small. With increasing time and increasing usage of space, the risk of collisions between active craft and debris has increased, and the risk of untrackable small debris has been recognised. In just the last few years, both ESA’s Sentinel 1A earth-observation satellite and the International Space Station have been damaged by strikes from debris particles less than a centimetre in size.

A relatively early science fiction narrative to address this concern was the short story “Deadly Litter” (1964), written by James White and published in an anthology of the same name. Here we encounter the crew of a spaceship specifically tasked with investigating the jettisoning of space debris - now considered to be a heinous crime. The focus of the story is the fate of an earlier spaceship which was damaged in an accident eleven years before. The crew of that ship attempted to lighten their load by placing as much unnecessary material as possible in the airlock and ejecting it. The fact that this was the only possible method of saving both the passengers and crew of the vessel is clearly in no way considered a mitigating circumstance in favour of the officers who took that decision. Given that the resulting debris cloud has since shredded two other spaceships and killed many of their crew, perhaps it is natural that a surviving officer is taken prisoner and held as a criminal for his actions:

A relatively early science fiction narrative to address this concern was the short story “Deadly Litter” (1964), written by James White and published in an anthology of the same name. Here we encounter the crew of a spaceship specifically tasked with investigating the jettisoning of space debris - now considered to be a heinous crime. The focus of the story is the fate of an earlier spaceship which was damaged in an accident eleven years before. The crew of that ship attempted to lighten their load by placing as much unnecessary material as possible in the airlock and ejecting it. The fact that this was the only possible method of saving both the passengers and crew of the vessel is clearly in no way considered a mitigating circumstance in favour of the officers who took that decision. Given that the resulting debris cloud has since shredded two other spaceships and killed many of their crew, perhaps it is natural that a surviving officer is taken prisoner and held as a criminal for his actions:

“The crime committed aboard the Sunflower eleven years ago had cost one ship and eighteen lives to date and the total would pile up for years to come, perhaps for hundreds of years to come.”

A striking feature of this narrative is how mundane the ejected materials are:

“There had been a time when people thought it funny that a ship could be wrecked by a few tea leaves, or a frigid, iron-hard potato peeling. But among spacemen, Gregory thought sourly, it was the sort of thing at which you died laughing.”

While modern space craft are unlikely to jettison their potato peelings, the existing debris field in earth orbit continues to shed everything from paint flecks to major components. As Arthur C Clarke noted in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968):

“One day, somebody had predicted, Earth would have a ring like Saturn’s composed entirely of lost bolts, fasteners and even tools that had escaped from careless orbital construction workers”.

Wrong place, wrong time

The danger of unregulated space extends far beyond tiny paint flecks or small objects. Although they are fewer in number, collisions between or accidents involving larger space vehicles have a still higher probability of causing catastrophic or life threatening incidents.

In 2009, the first recorded collision occurred between a defunct satellite (a Kosmos 2251 military craft) and another which was still active (the commercial Iridium 33). In 2019, a Chinese military satellite suffered an impact from another Russian craft. Also in 2019, the European Space Agency elected to manoeuvre one of their large scientific observatories (Aeolus) due to a close approach by a Starlink communications satellite. This latter incident highlighted the lack of a clear rulebook for orbit - while the Starlink craft was small, one of many in a satellite constellation, and the incident was considered by the SpaceX company to be a low risk event not requiring action [2], the ESA observatory was large, one of a kind, and demanded a much larger clearance. Without any form of international agreement regulating use of space, the operators were themselves forced to devise a sensible reaction to the event.

The need for some form of regulation of near-Earth space - and the risks inherent in ignoring it - were addressed within a few years of the first artificial satellite launch by the television series Thunderbirds (1965). In the episode “Ricochet”, we encounter International Space Control, who are responsible for tracking the orbit of every registered space craft, and are able to advise on a safe region in which to detonate a misfiring rocket. Unfortunately for all concerned, the crew of a space-based pirate radio station have illegally failed to register their orbit, and are caught by the explosion shockwave and debris. While the episode is a not-really-veiled-at-all morality tale about then-contemporary sea-borne pirate stations such as Radio Caroline (founded 1964), it is also prescient in identifying the danger of being in the wrong place at the wrong time to avoid space junk, and the desirability of accurate and up-to-date tracking.

The danger of being in the wrong place at the wrong time was demonstrated in the blockbuster film Gravity (2013, dir. Cuarón) - the debris of a disastrous space event results in a cloud of debris that tears through a space shuttle in flight, international space stations and other orbital installations. Each time, this generates further debris, kicked in a range of directions and moving at orbital velocities, causing extensive further damage to other vehicles. The same premises informs an episode of the animated series Thunderbirds Are Go (“Crash Course”, 2018) in which a routine collision between two space cargo freighters releases a cloud of damage fragments. This not only results in a flight-exclusion danger zone being declared, but amps up the threat level when the debris returns in its orbit to the collision site soon thereafter to cause further damage and risk to life.

The danger of being in the wrong place at the wrong time was demonstrated in the blockbuster film Gravity (2013, dir. Cuarón) - the debris of a disastrous space event results in a cloud of debris that tears through a space shuttle in flight, international space stations and other orbital installations. Each time, this generates further debris, kicked in a range of directions and moving at orbital velocities, causing extensive further damage to other vehicles. The same premises informs an episode of the animated series Thunderbirds Are Go (“Crash Course”, 2018) in which a routine collision between two space cargo freighters releases a cloud of damage fragments. This not only results in a flight-exclusion danger zone being declared, but amps up the threat level when the debris returns in its orbit to the collision site soon thereafter to cause further damage and risk to life.

In both these stories, the idea of the debris cloud’s inexorable return to its site of ejection through orbital dynamics effectively ratchets up the tension and adds a ticking clock to the drama. Unfortunately the remainder of the orbital mechanics in both these examples is rather suspect. Given the different relative speeds and motions of all the craft concerned, as well as various attempted orbital manoeuvres between impact recurrences, it’s highly unlikely that any of the craft involved would remain at the same orbital height over the Earth so as to perfectly intersect the original orbit.  Indeed given the range of their movements, they're likely to escape even the inevitable spreading of the debris cloud. The range of slightly different velocities of different fragments after a collision cause the narrow cloud (which follows the initial orbit) to gradually precess into a spherical shell at the same altitude.

Indeed given the range of their movements, they're likely to escape even the inevitable spreading of the debris cloud. The range of slightly different velocities of different fragments after a collision cause the narrow cloud (which follows the initial orbit) to gradually precess into a spherical shell at the same altitude.

[Image: Evolution of the debris field from a satellite collision in orbit. The initially narrow band of debris, returning to the collision point, fans out due to precession into a much broader debris belt. From Johnson et al (2008)]

The Kessler Syndrome

Nonetheless these chain-reaction stories highlight the very real risk that a simple case of wrong-time, wrong-place results in a chain reaction - known as the Kessler Syndrome, named after NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler who investigated the risk in the 1970s. Here each impact results in more debris being released, and this in turn results in more accidents in an exponentially-growing wave which will ultimately pound every vehicle in orbit to dust. The sequence of destructive impacts seen in the film Gravity is likely to represent the early stages of this syndrome, but occurs in very low Earth orbit (where residual atmospheric drag can cause debris to burn up and hence clear space relatively rapidly) and at a point where the density of space craft at this altitude is arguably too low to sustain the chain reaction. By contrast, other science fiction has explored the potential of a Kessler syndrome to cause a catastrophic debris field in high orbits or in geosynchronous orbits. Above 400 km, orbital lifetimes become much longer, with lifetimes for existing debris at 600-800km simulated at a century or more.

While the volume of space here is bigger, the number of artificial space craft - particularly communications and earth-observation satellites - is also growing exponentially, and the residual atmospheric drag is too weak to clear the debris field. A Kessler-syndrome event at geostationary orbit would create a long-lasting debris field and could potentially englobe the Earth, trapping humanity on the surface. While this is currently unlikely, since most of the extant geosynchronous satellites form a belt around the equator, it remains possible and even a dense debris field constrained to in and near this belt could have long term impact on communications and the ability to launch to near-ecliptic targets such as Solar System objects.

This scenario forms the background to fiction such as Frederik Pohl’s novel Homegoing (1989), which features a young man raised by aliens being brought to Earth for the first time. In this near-future humanity has been grounded - cut off from the stars by debris resulting in large part by a "Star War" which involved orbital weapons platforms (inspired by the Strategic Defense Initiative). As one character, herself a frustrated astronaut trainee, explains this hasn’t stopped humanity aspiring to reach the stars:

This scenario forms the background to fiction such as Frederik Pohl’s novel Homegoing (1989), which features a young man raised by aliens being brought to Earth for the first time. In this near-future humanity has been grounded - cut off from the stars by debris resulting in large part by a "Star War" which involved orbital weapons platforms (inspired by the Strategic Defense Initiative). As one character, herself a frustrated astronaut trainee, explains this hasn’t stopped humanity aspiring to reach the stars:

“Right,” she said bitterly. “We can’t get through the garbage ring. Unmanned satellites, yes, sometimes. We send them up every once in a while, and about one out of five of them survives for a year without damage. Well, without being totally destroyed, anyway. That’s not bad, for unmanned satellites. We can always make more of them. But it isn’t good enough odds to send up people. People are a lot more fragile.” (Gollanz paperback edition, 1991, pg 128)

Interestingly in this narrative, the threat of damage from de-orbiting debris, and possible technologies to remove it, become key plot points.

While the Kessler syndrome in Homegoing is a result of war and not necessarily an intended consequence, the scenario is actually weaponised by a rogue state in Orbital Cloud (novel, Taiyo Fujii, 2014). In this case a military satellite deliberately triggers a debris chain reaction, leading to a fight against time to prevent the planetary-grounding scenario.

Space Sweepers

If a space debris chain reaction has the potential to ground humanity permanently, perhaps it’s unsurprising that an extensive and growing range of science fiction has explored not only the threat but also possible ways to deal with it. Early examples of space debris clean-up are less than realistic [3]. One episode of the 1970 Television series UFO (“Conflict”) focussed on the possibility that alien spacecraft were using discarded rocket boosters and other large debris to provide cover for their attacks on human craft. The "International Astrophysical Commission" is shown as being in charge of clearing debris, and tracks a handful of large objects, but is wary of the cost a full-scale clear-up would require. Since their approach to this problem appears to be blowing up the offending debris - a process now known to massively increase the threat of collateral damage - this may actually be a good thing.

In The Lagrangists (novel, 1983), author Mack Reynolds suggests that future space colonists may actually salvage debris and mine it for raw materials. Again, the focus here is on clearing up the larger, heavier pieces of debris, while ignoring the problem of the far more abundant and dangerous micro-debris. The space-freight-dependent Thunderbirds Are Go (2015) universe of 2060 also shows astronaut Alan Tracy assigned debris clean-up duty in his rocket ship Thunderbird Three in order to prevent future accidents (and stumbling over an outdated stealth-mine, but that’s another story; “Space Race”). In the same series, we also encounter the Midpoint Salvage Exclusion Zone - a collection depot for large-scale space debris positioned at the Earth-Moon L1 gravitational balance point (which is unfortunately unstable, and so likely wouldn’t work as described; “Signal (part 1 & 2)”). This is policed by an automatic laser capable of vaporising any substantive debris that drifts away, but still fails to deal with the threat of millimetre and centimetre-sized particles - which, with a closing speed of 8 km per second, remain a substantial threat.

In The Lagrangists (novel, 1983), author Mack Reynolds suggests that future space colonists may actually salvage debris and mine it for raw materials. Again, the focus here is on clearing up the larger, heavier pieces of debris, while ignoring the problem of the far more abundant and dangerous micro-debris. The space-freight-dependent Thunderbirds Are Go (2015) universe of 2060 also shows astronaut Alan Tracy assigned debris clean-up duty in his rocket ship Thunderbird Three in order to prevent future accidents (and stumbling over an outdated stealth-mine, but that’s another story; “Space Race”). In the same series, we also encounter the Midpoint Salvage Exclusion Zone - a collection depot for large-scale space debris positioned at the Earth-Moon L1 gravitational balance point (which is unfortunately unstable, and so likely wouldn’t work as described; “Signal (part 1 & 2)”). This is policed by an automatic laser capable of vaporising any substantive debris that drifts away, but still fails to deal with the threat of millimetre and centimetre-sized particles - which, with a closing speed of 8 km per second, remain a substantial threat.

Routine debris collection itself is the focus of an increasing number of science fiction dramas. A notable example is the Japanese manga and anime series Planetes (2003). This follows the dramas and ambitions of a group of misfits who work for the “debris section” of Technora corporation… more often known as “half section” since it only has half the funding and personnel - and much less than half the respect - it needs or deserves. The drama itself is set seven years after a space passenger liner was destroyed by a single loose bolt drifting on an intersecting orbit - a dramatic scene seen in the first episode and referenced repeatedly throughout, indeed proving to be the source of personal trauma for one of the crew. This and similar incidents provide a constant motivation for their highly skilled and dangerous work.

Routine debris collection itself is the focus of an increasing number of science fiction dramas. A notable example is the Japanese manga and anime series Planetes (2003). This follows the dramas and ambitions of a group of misfits who work for the “debris section” of Technora corporation… more often known as “half section” since it only has half the funding and personnel - and much less than half the respect - it needs or deserves. The drama itself is set seven years after a space passenger liner was destroyed by a single loose bolt drifting on an intersecting orbit - a dramatic scene seen in the first episode and referenced repeatedly throughout, indeed proving to be the source of personal trauma for one of the crew. This and similar incidents provide a constant motivation for their highly skilled and dangerous work.

While the debris haulers of spaceship DS12 aka “Toy Box” are in a dead-end job and lack resources and self-belief, they truly believe in the importance of their work - particularly the young female protagonist who is shocked by how demoralised her new team is. The dedication of the whole team is explored explicitly in the episode “Debris Section, Last Day”, in which the sector is threatened with disbandment and each character is forced to confront their fear of what will happen in their absence. When a new manager confronts the usually obsequious and submissive assistant manager of the section, threatening to strand the DS12 in space, he provokes a furious response:

Manager: “I swear, give me debris any day. We can recycle debris and make money off it… unlike you people, right? Junk jockeys becoming debris themselves is poetic justice. Now that I’m division director, things will be different.”

Assistant Manager: “Even if you think you don’t need us in your division, the rest of the human race needs us!”

The anime was developed with technical advice from scientists associated with Japanese space agency JAXA and worked hard to site itself as an accurate vision of a potential future. The astronauts are vulnerable to the health risks as well as the physical dangers of space travel, and the threat of space debris is shown with grim honesty. Its opening sequence features a visualisation of the orbital space debris cloud multiplying over time, projected over the next century, and a serious narration:

“Abandoned artificial satellites. Tanks jettisoned from shuttles. Refuse generated during space station construction. This vast amount of junk floating in space - space debris - is a very serious threat to everything in orbit. This is a story of 2075: a time in which this space debris has become a major problem.”

While most of the debris retrieved by the crew is again relatively large, and ranges from discarded vehicles to memorial plaques and a space-burial coffin, the scripts demonstrate a constant concern for the production of secondary debris (chips and paint flakes due to collisions or damage during junk collection). We also see smaller material gathered up in bulk and assigned a value based on either environmental or material worth (it’s sometimes a little unclear which), and the series engages in an extended conversation about the equity of space utilisation and its denial to developing nations. Just as tightening of environmental regulations on Earth makes it harder for developing nations to establish their own industries at the required standard, so it could have the same effect on access to space. Planetes also gives an explanation and example of weaponisation of the Kessler Syndrome - the episode “A Modest Request” features a terrorist group that objects to human space utilisation, and attempts to collide a communications satellite with a major space station, starting the chain reaction and grounding humanity.

A similar theme of debris collection as an important, but low-esteem and poorly-rewarded job in near-future space utilisation can also be found in the recent Korean feature film Space Sweepers (2021, dir. Sung-hee [4]). Here an orbital clean-up crew recovers a military device in the form of a child android - placing them in the midst of both political and moral dilemmas. As usual for space debris stories, the crew is cast as misfits and rebels, and again the crew are working for profit - selling their hauls to a company store.

In actuality, real world technologies under development for space clean-up are almost entirely automated or remote-controlled, and range from capturing craft with spears (which risks secondary debris generation) to nets designed to sweep up bulky debris and drag it down into Earth’s atmosphere. A technique under development for dealing with slightly smaller (~1cm) debris is laser ablation - sweeping orbit with lasers to reduce the angular momentum of flakes or objects, causing them to deorbit. One thing that all these technologies have in common however is that they are designed to deal with relatively large debris, rather than the uncountable millions of smaller particles which now threaten space vehicles. In the long run, such routine clean-up may be sufficient to prevent a Kessler syndrome, or even the kind of more isolated collisions that have already been seen in orbit, reducing the amount of such micro-debris. However in the short to medium term at least it seems likely that human-created threats to life and function in orbit will exceed those from natural micrometeorites, and that debris will be a problem for generations to come.

In space, humanity really is becoming its own worst enemy.

“Space Sweepers”, Elizabeth Stanway. Cosmic Stories blog. 16th October 2022.

Notes:

My thanks to James Blake of the Warwick Centre for Space Domain Awareness for fact checking and useful comments on this blog post! Any remaining errors are, of course, my own.

[1] I mean really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space… (Adams, 1978). [Return to text]

[2] According to online rumour, it is possible that an internal miscommunication inside SpaceX may also have contributed to their inaction. [Return to text]

[3] Let’s not even mention the execrable situation ‘comedy’ Quark - which features a misfit space trash crew manning a garbage scow working for the United Galaxy Sanitation Patrol - the little of it I’ve seen was more than sufficient to tell that it has not aged well. [Return to text]

[4] I have to admit to not having seen Space Sweepers, which I believe is currently available on Netflix. [Return to text]

This blog represents a personal opinion and interpretation, and does not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Warwick.

All images sources online from public domain sources, and used here for criticism and commentary.