Time-Travelling Historians

Historians are those who study the past, in order to understand the nature, course, causes and impacts of historical events or patterns. In many cases, they must do so through interpreting incomplete evidence, or relying on second or third-hand accounts, written long after an event. In science fiction paradigms in which time travel is a possibility, it’s perhaps unsurprising that time-travelling historians are a common feature. Maybe more surprising is what can be learned about both history and science in such narratives.

Time travel itself is a very, very big topic. I’ve touched on it in the past in talking about alternate histories of science and the problem of predestination paradoxes. In order to keep this manageable (and it’s still a long one!), I’m going to focus here specifically on historians - those who use (or intend to use) time travel specifically to study the past without intent to change it. I’m going to avoid stories about time travel technology development, those deliberately setting out to change the past, or the time police who attempt to prevent such changes - I might return to these another time! Fair warning: given the time-theme, the moral of the story is often presented as a punch line or twist at the end, and so it is impossible to avoid spoilers in some of the examples below.

Unravelling our Past

The idea that aspects of our past are lost beyond recovery is a fact that has always faced historians. Centuries of decay, fires, floods, wars and other disasters have destroyed vast quantities of records, while much factual information may never have been committed to writing in the first place - particularly information regarding the trivialities of everyday life and the lives of those low in social status or formal education. Hence fragmentary information is reconstructed and reinterpreted by those increasingly distanced from its original source.

Almost as soon as time travel started to be theorised, stories began to appear which suggested their use as historical research tools. An early example, The Dead Past by Isaac Asimov (novelette, Astounding SF, April 1956), highlights both the motivations of, and risks taken by, such projects. In The Dead Past, Asimov assumes the existence of a device which allows not people or objects but instead information to be transported from the past to the present. This device is a chronoscope - a viewer through time, which works by detecting and analysing neutrinos (an unlikely prospect, to say the least!). However in a society in which individuals are constrained to extremely narrow and tightly-controlled specialisations, Professor Arnold Potterly, a historian who wishes to explore the truth of ancient Carthaginian child sacrifice stories. finds himself unable to secure access to the device. Breaking laws regarding specialisation, he recruits a young physicist to build a chronoscope of his own. However the device proves to be limited to the relatively recent past by the uncertainty principle, and its potential leads the historian’s wife to have a breakdown caused by her desire to obsessively watch the young daughter they lost.

Almost as soon as time travel started to be theorised, stories began to appear which suggested their use as historical research tools. An early example, The Dead Past by Isaac Asimov (novelette, Astounding SF, April 1956), highlights both the motivations of, and risks taken by, such projects. In The Dead Past, Asimov assumes the existence of a device which allows not people or objects but instead information to be transported from the past to the present. This device is a chronoscope - a viewer through time, which works by detecting and analysing neutrinos (an unlikely prospect, to say the least!). However in a society in which individuals are constrained to extremely narrow and tightly-controlled specialisations, Professor Arnold Potterly, a historian who wishes to explore the truth of ancient Carthaginian child sacrifice stories. finds himself unable to secure access to the device. Breaking laws regarding specialisation, he recruits a young physicist to build a chronoscope of his own. However the device proves to be limited to the relatively recent past by the uncertainty principle, and its potential leads the historian’s wife to have a breakdown caused by her desire to obsessively watch the young daughter they lost.

The story focuses on the ethics of authoritarian control over the direction and restriction of scientific research, and the potential disadvantages of over-specialisation. In a twist at the end of the narrative, the reluctance of the authorities to allow widespread use of the chronoscope proves to be a public protection measure - as they point out, the past begins just microseconds away from the present, so any precise chronoscope is also an extremely effective and unblockable spying device.

The Dead Past was adapted for television by Jeremy Paul, for the well regarded BBC Drama science fiction anthology series Out of the Unknown in 1965, and - unusually for this early series - the episode survives in the archives. This fairly faithful adaptation emphasised the finale of the story and the characters motivations while lingering a little less on the academic aspects. However, this short story (in both formats) touches on a surprising range of themes - the dangers of overspecialisation, the questions associated with tight government control of academia, the dangers of misuse of new technologies and the guilt of the parents who survived their daughter.

On a lighter note, Asimov also visited this theme the same year in his very short story "The Message" (F&SF, Feb 1956). Here we find a travelling historian called George Kilroy leaving his mark on the past, and starting a new tradition in the process.

Other authors have explored the concept of a much more active form of historical research - time travel of present (or near-future) humans who can move through, experience and interact with the past. A striking example here can be found in the novels of Connie Willis, mostly standing alone but loosely grouped into a sequence known as the Oxford Time Travel series. These imagine a near-future in which an under-resourced but dedicated group of historical workers are based at Oxford University. They have access to a time travel device that can send individuals back in time - at great expense - and retrieve them at a pre-arranged time and place.

The first story, Fire Watch (novella, 1982) describes the experiences of a history student who is assigned to join the watchmen protecting St Paul’s cathedral against incendiary bombs during World War II. Through traumatic experiences he reaches a very different view of the role of a historian by the end than he held at the beginning of the assignment. Willis returned to the basic premise a decade later, in a novel actually set before Fire Watch, rather than after. In Doomsday Book (novel, 1992), a research student named Kivrin Engle is sent back to investigate the English Middle Ages. However instead of being sent to 1320, she finds herself in 1348, the year the Black Death (bubonic plague) swept through England. At the same time, in the Oxford of 2054, a lethal influenza-like virus breaks out and causes death and devastation. Crucially it also delays the realisation of Kivrin’s situation and any attempt to recover her. Both Kivrin and the Oxford historians face a battle for survival through traumatic events

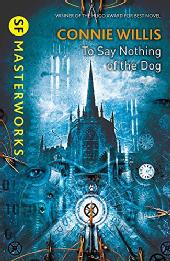

The next novel in the series, To Say Nothing of the Dog (1998) was a more comedic novel. It centres on a historian dispatched from 2057 to obtain information about an artefact lost in 1940. The “Bishop’s Bird Stump”, a rather ugly decorative vase from the nineteenth century, is believed to have been destroyed during the 1940 bombing of Coventry Cathedral and a detailed description is needed to satisfy a politically and financially influential benefactress who is seeking to rebuild the cathedral, exact in every respect. The desperate search for information is complicated by inaccurate time-space coordinates, and by mental confusion on the part of the investigator, who is suffering from severe time lag. It takes him into the heart of the Coventry Blitz and the traumatic burning of the cathedral itself.

The next novel in the series, To Say Nothing of the Dog (1998) was a more comedic novel. It centres on a historian dispatched from 2057 to obtain information about an artefact lost in 1940. The “Bishop’s Bird Stump”, a rather ugly decorative vase from the nineteenth century, is believed to have been destroyed during the 1940 bombing of Coventry Cathedral and a detailed description is needed to satisfy a politically and financially influential benefactress who is seeking to rebuild the cathedral, exact in every respect. The desperate search for information is complicated by inaccurate time-space coordinates, and by mental confusion on the part of the investigator, who is suffering from severe time lag. It takes him into the heart of the Coventry Blitz and the traumatic burning of the cathedral itself.

The historians in this series believe themselves to be somewhat protected from accidentally (or intentionally) changing history by “slippage” - a displacement in either time or space that occurs when a time traveller attempts to approach an event of lasting significance, and which prevents them from doing so. However Willis eventually challenges this complacency. While the earlier novels had suggested only one or two researchers might be out at any one time, the two-part novel Blackout and All Clear (both 2010) describes a more bustling history department operating a few years later in 2060, from which literally dozens of research trips are launched, monitored and retrieved every day. Willis returned to some of the same themes as her earlier novels, sending many of her student researchers into the midst of the Second World War in London. Unfortunately, this acceleration in time travel research activity results in increasing amounts of slippage, and hints that all might not be well with the structure of history itself, leaving some students trapped in a traumatic time very different to their own.

A similar premise, albeit one written from a different angle, can be found in the long-running Chronicles of St Mary’s series written by Jodi Taylor (short stories and novels, starting with Just One Damned Thing After Another, 2013 - present). These are overtly comic, albeit with tragic and emotive incidents. These are set in a near-future in which social unrest has changed the structures of power across the country, and the small Yorkshire town of Thirsk is home to a research university. The St Mary’s Institute for Historical Research is based nearby in the (fictional) town of Rushford, and “researches historical events in contemporary time” using time-travelling pods in the form of small shacks. These can be transported to different space time coordinates and blend inconspicuously with most surroundings. While loosely associated with the University at Thirsk, St Mary’s has its own technical, administrative, costume, security and history departments, all of which operate with varying degrees of chaotic and/or comedic effectiveness.

A similar premise, albeit one written from a different angle, can be found in the long-running Chronicles of St Mary’s series written by Jodi Taylor (short stories and novels, starting with Just One Damned Thing After Another, 2013 - present). These are overtly comic, albeit with tragic and emotive incidents. These are set in a near-future in which social unrest has changed the structures of power across the country, and the small Yorkshire town of Thirsk is home to a research university. The St Mary’s Institute for Historical Research is based nearby in the (fictional) town of Rushford, and “researches historical events in contemporary time” using time-travelling pods in the form of small shacks. These can be transported to different space time coordinates and blend inconspicuously with most surroundings. While loosely associated with the University at Thirsk, St Mary’s has its own technical, administrative, costume, security and history departments, all of which operate with varying degrees of chaotic and/or comedic effectiveness.

Almost every plan made by the institute’s members goes wrong to varying degrees, often (but not always) in an amusing manner. Across a lengthy series of adventures, they nonetheless investigate a large number of historical events and scenarios, including lesser known events of interest in the history of technology, such as the seventeenth century demonstration of the steam pump at Raglan Castle. They also learn to their cost the limits of their time travel - both technologically and in terms of the limits placed on their activities by history (or occasionally a very definitely capitalised and personified History) itself. A historian who attempts to interfere with the past usually ends up dead... often painfully. One interesting tool employed in the series is a way of circumventing limitations on the transport of objects outside their own time: an object that would otherwise be lost to history (and so won’t affect the recorded or genetic timeline by its removal) can be moved and buried somewhere safe in its own time for later recovery by contemporary (i.e. twenty-first century) archaeologists. This way nothing except the original travellers is actually displaced in time, but objects can still be preserved for later study or artistic value.

Time travelling historians have also appeared on screen. The Time Tunnel was an American television series produced by Irwin Allen which ran for a single season of 30 episodes in 1966-7. Here a giant machine has been built under the deserts of the southern USA in a ten year project. Its interior forms a gigantic (and rather psychadelic) tunnel vanishing into the distance. This permits individuals to travel to (and, theoretically, be recovered from) incidents in the past. However not everyone is convinced its cost is justified. As a visiting senator notes, in conversation with the lead scientist in the pilot episode:

Time travelling historians have also appeared on screen. The Time Tunnel was an American television series produced by Irwin Allen which ran for a single season of 30 episodes in 1966-7. Here a giant machine has been built under the deserts of the southern USA in a ten year project. Its interior forms a gigantic (and rather psychadelic) tunnel vanishing into the distance. This permits individuals to travel to (and, theoretically, be recovered from) incidents in the past. However not everyone is convinced its cost is justified. As a visiting senator notes, in conversation with the lead scientist in the pilot episode:

“You know, Phillips, every time I check your budget figures, I ask myself the same question: is time travel really worth all this?”

“Senator, the control of time is potentially the most valuable treasure that Man will ever find.”

This threat to the project funding provokes another of the project scientists, Tony Newman, to embark before the device is fully tested. Doug Phillips follows, and the remainder of the series consists of unsuccessful attempts to retrieve the two of them or remove them from a variety crises by causing shifts to a different time zone at the end of each episode. Meanwhile the researchers at the Time Tunnel itself can monitor the experiences of the travellers, watching and listening to events as if on a screen. The series was set in 1968, and the tunnel had a range extending from the ancient past to the distant future (although arrival at recorded historical events within the last few centuries was most common).

Curiously, the purpose of the tunnel is never really made clear on the screen. From the perspective of the builders it appears to be an exercise primarily in testing theoretical physics. There is little concern for causality here. Indeed, Newman and Phillips’ first action in the past is to attempt to inform the captain of the Titanic that his ship is about to sink. However, in application, the tunnel is certainly used primarily for historical research, and a number of history experts are called in throughout the series to help clarify certain situations [1]. It’s also interesting to note that in the two spin-off novels for The Time Tunnel, written by science fiction author Murray Leinster based on an early treatment for the series (The Time Tunnel and Time Tunnel 2: Timeslip, both 1967), the scientists have far greater control over their travel and can use it in a similar fashion to Asimov’s chronoscope in The Dead Past - visiting very recent and near-contemporary history as a form of Cold War-era espionage.

Of course, when discussing time travel on television, it’s impossible to ignore the best known time-travel saga - Doctor Who (TV, 1963-1989, 2005-present). In this case, the routine time travel is via an alien device and not primarily for the purposes of research. However a few examples are worth considering in this context. One of the First Doctor’s companions, Barbara, was a history teacher. She may not have set out to research different eras of history, but she showed a strong interest in finding out more about each location (although it’s worth noting that she sometimes felt the need to impose her own modern world view on them, as was notably the case in "The Aztecs").

Perhaps a more interesting example can be found in the Doctor Who audio drama "The Lady of Mercia" (written by Paul Magrs for Big Finish Productions, 2013). In this story, the Fifth Doctor and his companions Tegan, Turlough and Nyssa visit the University of Frodsham. Here a history professor, John Bleak, and his physics professor wife, Philippa Stone, are cooperating on a project [2]. As in the case of The Time Tunnel, Dr Stone sees this as primarily a physics project, but her husband is determined to use her device to learn the truth about the early mediaeval queen of Mercia, Æthelfrid. As Stone explains to the Doctor and his companions:

“It was so seductive, especially to a historian. To me, it was about testing out the theory. But to him…”

“Bleak was more concerned with the machine’s practical applications.”

“He had a plan for a whole new school of historical research. Empirical research into the past.”

“You mean actually travelling back into the past and finding things out for himself?”

“No, no. He didn’t want to go into the past. He wanted to bring the past here. He wanted to bring people out of history and into this laboratory.”

Confusingly, Æthelfrid here appears to be a renaming on the part of the writer for the historical Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred of Wessex and wife of King Æthelred of Mercia before she took power in her own right as Lady of Mercia in the period 911-918 AD. No other names or major historical events are changed.

Confusingly, Æthelfrid here appears to be a renaming on the part of the writer for the historical Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred of Wessex and wife of King Æthelred of Mercia before she took power in her own right as Lady of Mercia in the period 911-918 AD. No other names or major historical events are changed.

Here the intent of Professor Bleak is very definitely to use the time viewer as a research tool to investigate the end of the Mercian dynasty. However one of the Doctor’s companions is accidentally sent back in time, while Ælfwynn, the daughter of Queen Æthelfrid, is transported forward to the present. In the resultant confusion, both the Doctor and Professor Bleak return to early mediaeval Mercia, and we witness the annexation of the Mercian kingdom by Wessex from a very different perspective to that recorded in the history books.

The Present Under a Spotlight

A rarer but still significant thread in the science fiction of time-travelling historians provides a different view. Rather than considering the examination of the past by contemporary (or near future) academics, this considers examination of the present by historians dispatched from the distant future.

This premise is presented without undue seriousness in a pair of films better known as comedy than as science fiction. Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989, dir: Herek), and its more fantastic sequel Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991, dir: Hewitt) follow the adventures of the titular American teenagers. Academic failures, with an apparently low intelligence quotient, William S Preston Esq and Theodore Logan show little sign that they will have a significant impact on the world around them. However a traveller from the 27th Century informs them that their rock band, the Wyld Stallions, and the philosophy they espoused through its publicity - “Be Excellent to Each Other” - will change the path of civilisation.

This premise is presented without undue seriousness in a pair of films better known as comedy than as science fiction. Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989, dir: Herek), and its more fantastic sequel Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey (1991, dir: Hewitt) follow the adventures of the titular American teenagers. Academic failures, with an apparently low intelligence quotient, William S Preston Esq and Theodore Logan show little sign that they will have a significant impact on the world around them. However a traveller from the 27th Century informs them that their rock band, the Wyld Stallions, and the philosophy they espoused through its publicity - “Be Excellent to Each Other” - will change the path of civilisation.

This time traveller, Rufus, is a history teacher who has studied the past (the film’s contemporary time). He intervenes to prevent the band being disrupted as a punishment for a failed history course. Instead he takes Bill and Ted through time in order to gather information and examples for a presentation which sets their paths back on - from Rufus’s perspective - the correct course. Here, then, we see a historian from the future observing the present, as well as two teenagers from the present (of c.1990) observing both the present and the past. While little of it is plausible or taken entirely seriously, the differences in perspective and expectation serve to highlight the absurdities in each timezone - including our own.

In the second film, Chuck de Nomolos, a dissident historian from the 27th Century, develops a loathing for the state of his society. Stealing a time machine, de Nomolos returns to try and kill Bill and Ted. He apparently succeeds, leading the protagonists to journey through the underworld in search of revival, while evil robot replicas take their place. While the plot has roots in mythology and folklore, the finale mixes these with the science fictional tropes of aliens, robots and time travel to show how the band rises to the heights of its fame.

Still relatively lighthearted, but less overtly comic than Bill and Ted is a work by William Tenn that also explored the theme of time-travelling historians, and their implications for the nature of identity. In his short story “The Discovery of Morniel Mathaway” (Galaxy magazine, October 1955; adapted for radio anthology series X-Minus-One in 1957), a bohemian painter, Mathaway, and his poet friend are startled by the appearance of Glasco, a visitor from the distant future. They learn that in the distant future, one traveller in every fifty years is awarded a trip through time as a prize of academic excellence. Rather to their surprise, Glasco declares that the unknown and untalented Mathaway will one day win fame and become his specialist subject. The first person narrator ponders his surprise:

Still relatively lighthearted, but less overtly comic than Bill and Ted is a work by William Tenn that also explored the theme of time-travelling historians, and their implications for the nature of identity. In his short story “The Discovery of Morniel Mathaway” (Galaxy magazine, October 1955; adapted for radio anthology series X-Minus-One in 1957), a bohemian painter, Mathaway, and his poet friend are startled by the appearance of Glasco, a visitor from the distant future. They learn that in the distant future, one traveller in every fifty years is awarded a trip through time as a prize of academic excellence. Rather to their surprise, Glasco declares that the unknown and untalented Mathaway will one day win fame and become his specialist subject. The first person narrator ponders his surprise:

“It just proved, I kept saying to myself, that you need the perspective of history to properly evaluate anything in art. You think of all the men who were big guns in their time and today are forgotten — that contemporary of Beethoven's, for example, who, while he was alive, was considered much the greater man, and whose name is known today only to musicologists.”

In this respect, it anticipates the Bill and Ted narrative - the unlikely unknown whose influence reshapes future civilisation. However the narratives diverge in the finale of the story: the life-story of the creative figure of legend in Tenn’s short fiction proves to be very different from that in the historical record. Here we see a reminder that our historical perspective might not be as robust as we thought - just as Glasco’s understanding of our own time proved flawed.

Sometimes in science fiction, the challenge to our contemporary worldview is overt and pointed. The British television science fantasy series Sapphire and Steel (written by P J Hammond for ITV, 1979-1982) was preoccupied with the nature of time. The origin of its central characters, clearly not human, was never explained, and many of their abilities are extrasensory in nature - although apparently rooted somewhat in an understanding of physics. They responded to faults in the nature of time, often caused by a conflict between old and new, with time itself personified as a formless and shapeless but somewhat aware primal force. In one serial (known as "Assignment Three"), the fault in time is caused by the presence of a young couple and their infant who have been projected from about 1500 years in our future into their past (to 1980) in order to study our contemporary way of life. This experiment in twentieth century urban living (known as ES/5/777) takes place in a closed capsule on the roof of an apartment building. This is a simulated but not a real environment. As the female time traveller notes, looking out of the window before the capsule begins to break down: "Outside...? Well, I'd hate to imagine how we'd survive outside."

Sometimes in science fiction, the challenge to our contemporary worldview is overt and pointed. The British television science fantasy series Sapphire and Steel (written by P J Hammond for ITV, 1979-1982) was preoccupied with the nature of time. The origin of its central characters, clearly not human, was never explained, and many of their abilities are extrasensory in nature - although apparently rooted somewhat in an understanding of physics. They responded to faults in the nature of time, often caused by a conflict between old and new, with time itself personified as a formless and shapeless but somewhat aware primal force. In one serial (known as "Assignment Three"), the fault in time is caused by the presence of a young couple and their infant who have been projected from about 1500 years in our future into their past (to 1980) in order to study our contemporary way of life. This experiment in twentieth century urban living (known as ES/5/777) takes place in a closed capsule on the roof of an apartment building. This is a simulated but not a real environment. As the female time traveller notes, looking out of the window before the capsule begins to break down: "Outside...? Well, I'd hate to imagine how we'd survive outside."

As in many of the examples above, their understanding of that way of life is limited and rife with misconceptions, and Time itself acts to isolate them, cutting off their supply chain, and disrupting their experiment. Memorable scenes challenges the morality of both present and future: the time travellers eat cultured meat in an attempt to reproduce the diet of the present, and use feather pillows, but are assaulted by horrific imagery of slaughter houses and livestock. However, as the title characters demand to know, is the existence of biological meat cultures (which never had a life, yet form part of the future technology) any more moral than the existence of the farmed animals they replaced? Interestingly, the writer also takes an opportunity to explore the extrapolation of contemporary culture. As well as portraying a future in which animals are extinct, it's notable that he shows the male character Eldred as hesitant and ineffective when compared to his partner Rothwen. It's not entirely clear whether this is meant to be representative of the nature of masculinity in the future, but it adds an intriguing element to the story.

Views from a Different Angle

Interestingly, the Star Trek universe provides examples of time travellers in two different contexts. The first fits the pattern of several of the examples above. In the Original Series episode “Assignment: Earth” (TV, 1968), the USS Enterprise of the 2260s is dispatched to the present of 1968 to make historical observations of cold war nuclear proliferation [3]. Intended to observe from a shielded undetectable orbit, there is no intention for them to do more than monitor and record events, although this plan is derailed through a chance encounter with another traveller on a very different mission. Here there is relatively little agonising over the nature of time or interpretation: instead, the horror of the characters regarding nuclear proliferation in the present carries a clear moral message.

Interestingly, the Star Trek universe provides examples of time travellers in two different contexts. The first fits the pattern of several of the examples above. In the Original Series episode “Assignment: Earth” (TV, 1968), the USS Enterprise of the 2260s is dispatched to the present of 1968 to make historical observations of cold war nuclear proliferation [3]. Intended to observe from a shielded undetectable orbit, there is no intention for them to do more than monitor and record events, although this plan is derailed through a chance encounter with another traveller on a very different mission. Here there is relatively little agonising over the nature of time or interpretation: instead, the horror of the characters regarding nuclear proliferation in the present carries a clear moral message.

However in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “A Matter of Time” (TV, 1991) we don’t see a contemporary historian travelling to the past, or a future historian visiting the present, instead we find the future being visited by a historian of the still more distant future. This individual, Professor Rassmussen, has apparently selected the Enterprise, and Captain Picard specifically, as his specialist subject. When the population of a planet is threatened, Picard demands to know how Rasmussen can reconcile his silence regarding the future with their potential deaths. As the visitor points out, for him, their fate - whatever it is - is distant history for him. During their discussion Picard asks about the existence of a temporal equivalent of the Prime Directive of non-interference, without receiving a satisfactory reply.

As in many of the cases discussed here, the time traveller proves not to be all he seems and has plans of his own.

An interesting aspect of this encounter is where it fits into the history of shifts in the Star Trek worldview. Star Trek was originally created as a fundamentally an optimistic view of the future, in which the Federation acts as near-utopian vision of future governance, and the characters are content in their moral and intellectual superiority over, for example, our time (as seen in "Assignment: Earth"). Having a distant future historian from the late 26th Century visit the early 24th Century in “A Matter of Time” to examine the characters and their decisions highlights the gradual shift towards self-reflection in later entries in the Star Trek canon. In these the flaws in that initial premise - and indeed the idea that any society can be truly utopian from all viewpoints - are challenged.

Providing a different perspective again, we find another Irwin Allen-produced science fiction television series Land of the Giants (TV, 1968-1970). In the episode “A Place Called Earth” (TV, 1969) we encounter another pair of historians from the distant future - in this case the year 5477. The story begins with a description of their mission in the voice of authority:

Providing a different perspective again, we find another Irwin Allen-produced science fiction television series Land of the Giants (TV, 1968-1970). In the episode “A Place Called Earth” (TV, 1969) we encounter another pair of historians from the distant future - in this case the year 5477. The story begins with a description of their mission in the voice of authority:

“Olds, Fielder, your mission is routine. You travel back in time 100 years. You make observations for 2 hours in real time, and then you will return here. During your stay in the past, you are warned to do nothing that will change the course of history in any way.”

However one of the men proves to be a renegade and instead sets the destination for 5000 years past. It comes as a surprise to Olds and Fielder to discover that the world they’re visiting is not only the near-future of 1983 (as seen from a 1969 perspective) but also a different planet entirely - the giant-dominated planet on which the crew of the Spindrift (representatives of the series’ Earth) are themselves stranded. They take the surprise in their stride: while the time travellers’ original mission was historical research, they have plans of their own.

Perceptions and Prejudice

The examples of time travelling historians above span a range of perspectives and vary in emphasis. However a number of common themes emerge.

Where historians are sent deliberately into the past, perhaps the biggest issue is one of causality protection - whether it is possible for the travellers to change that past in any way significant enough to negate their own future existence. In some fictions related to this topic, which focus on time travel theory itself, the actions of the travellers do destroy their timeline. In others, those actions result in the production of an alternate or parallel history, rendering the original timeline inaccessible but not destroying it. This would be the case, for example, if the renegade historians de Nomolos (in Bill and Ted) or Olds and Fielder in Land of the Giants were to succeed in their plans.

However deliberate history manipulation or direct speculation on the nature of time is relatively rare in these history narratives. Indeed, many of the narratives above (for example the Oxford Time Travel series, Chronicles of St Mary’s or Doctor Who) assume that there is some poorly-understood but nonetheless fundamental limitation that prevents the time travellers from making substantive changes in the past. Such chronology protection principles are also implicit in a number of other stories, for example in Star Trek or Bill and Ted, in which the actions of the time travellers prove to be fundamental in setting up their own history. The time travellers can’t have changed the course of time because their time travel was always part of the established chronology.

In some of these stories, notably Sapphire and Steel and in the Oxford and St Mary’s books, Time (or equivalently History) itself is personified - described as having a purpose and an intention that may or may not include the safety of the travellers in question. In the case of Taylor’s Chronicles of St Mary’s, a recurrent character (who watches most of the adventures from the sidelines but intervenes at key moments) proves to be the ancient Greek muse of history - the goddess Clio. It’s not made entirely clear to what extent her actions are manifestations of a greater force of History, to what extent she controls that force, and to what extent she is under its control, but she certainly has the power to affect key events by her actions.

Taylor’s decision to bring religion into her fiction, albeit a no-longer-current form of ancient worship, highlights an interesting aspect of these narratives. In many cases of historians visiting the past, narrative tension is derived from the very different worldviews in the two or more times in question. For any story that involves travel into our own past, a defining characteristic of such worldviews is likely to be their differing attitudes towards science and religion. Religious explanations for any unusual event were common in Europe until well into the modern period, and in time travel fiction are often contrasted against an emphasis on scientific interpretations that verges on scientism (i.e. a faith in a specific interpretation of the world that mirrors religion in its unquestioning certainty). A key example here is The Time Tunnel: although the travellers have historical interests, they are physicists by training and show a stereotypically scientistic approach in their dismissal of the more traditional knowledge of those they encounter.

This is, of course, an oversimplistic view and represents its wider contemporary 1960s culture as much as (if not more than) a wider scientific culture of today. The portrayal of our ancestors as superstition-ridden and hostile is equally oversimplistic. Many intellectuals throughout history have had a firm grasp of scientific principles and a questioning approach to new information. And many scientific and academic researchers of the present remain people of faith. Fiction that acts to highlight the contrast between past and future, science and religion, nonetheless acts to throw both into a sharper critical light.

One recurring approach amongst the more thoughtful writers on this theme is to challenge this idea that history is entirely a matter of contrasts. Stories such as the Oxford Time Travel series and the Chronicles of St Mary’s emphasise time and again that the people of the past are as real, as intelligent and as varied as those of the present (or near future). These stories challenge the arrogance of assuming that a more modern viewpoint is necessarily a superior one, humanising the characters of both periods and often showing both viewpoints as equally valid in different ways. This is also often an aspect of stories in which future time travellers explore and critique our present. Characters such as Olds and Fielder in Land of the Giants treat our (near-)contemporaries with an arrogant sense of superiority, reminding us to question whether travellers from today into the past are similarly offensive.

In the Doctor Who audio adventure “The Lady of Mercia”, for example, a character defends Bleak's intentions with an unconsciously arrogant remark: “It was in the cause of knowledge! All he wanted to do was to shed some light upon the Dark Ages.” The rest of the story serves to highlight the humans on which light was being shed as more than mere subjects. The use of the somewhat pejorative term "Dark Ages" for early mediaeval England is now being questioned and seen as prejudice on the part of the historians who used it, implying a degenerate culture. In fact the culture of the time was largely an oral tradition rather than written, but it was far from barbaric and included complex legal systems and exquisite art.

However possibly the main theme of all historical investigations in science fiction is to remind us of the impossibility of making impartial observations. As one character in Connie Willis’ novel Blackout notes:

However possibly the main theme of all historical investigations in science fiction is to remind us of the impossibility of making impartial observations. As one character in Connie Willis’ novel Blackout notes:

“It was the one thing historians could never understand. They could observe the contemps, live with them, try to put themselves in their place, but they couldn’t truly experience what they were experiencing. Because I know what’s going to happen. I know Hitler didn’t invade England, that he didn't use poison gas or destroy St Paul’s. Or London. Or the world. That he lost the war. But they don’t.” (pg 218)

While history used to be considered a matter of collecting facts, it is now widely recognised that interpretation of those facts is unavoidably coloured by our own perceptions, background knowledge and social context. The personal history of the scientist in Asimov’s The Dead Past influences both his determination to access the chronoscope and his eventual conclusion that it shouldn't be used. The relative immunity to disease of “modern” historians may give them a casual confidence in facing pestilence, until they see its impacts on those without such aid (as in Willis’ Doomsday Book) or are trapped without it themselves (as in Taylor’s novel A Trail through Time, 2014). Similarly the casual dismissal of practices common to one time as “barbaric” (as in Star Trek or Sapphire and Steel or even Doctor Who) can question which other practices, fully accepted by the time travelling historians, would seem equally barbaric either as seen from the past or from the future.

The involvement of physicists in many of these stories, and the contrasts made between them and their historian colleagues also suggests another role these stories play. In highlighting how much of history is interpretation rather than fact, and how the cultural and social context affect that interpretation, these stories remind us that scientists are humans too. While scientific facts can and do exist, in many cases these have to be gathered into a bigger structure of interrelated facts known as a theory or hypothesis through experimentation and interpretation of empirical results. In physics, the goal of those interpretations is to make firm and quantitative predictions that can themselves be tested by further experimentation or mathematical formalisms based on the interpretation. This predictive power establishes a theory in scientific parlance as closer to a law as interpreted by non-scientists. However even in exploring new aspects of an established theory, a subjective element remains. The goal of most scientists is to weigh the evidence against that subjectivity, recognising and attempting to set aside their own preconceptions and biases. However as for any human, in any one individual that is a challenging task, and even the scientific consensus can occasionally be mistaken.

Just as historians are occasionally forced to change their interpretation when new evidence is gathered - whether through revelations from new sources, or through science-fictional time travel - scientists must also be willing to change their interpretation when new data adds to our body of knowledge, and to recognise their prejudices in the light of the factual evidence. The science fiction of time travelling historians is a reminder of this, and an opportunity to compare and contrast the worldviews of two very different disciplines, as well as a window into aspects of society past and present, and humanity at all times.

“Time Travelling Historians”, Elizabeth Stanway, Cosmic Stories blog. 2nd June 2024

Notes:

[1] The premise of The Time Tunnel bears a strong resemblance to Quantum Leap (TV, 1989-1993), although in the latter case the focus is on the lives of individuals rather than key historical events, and the physicist time traveller essentially possesses participants rather than acting as an observer. There is no overt history research objective. [Return to text]

[2] The Fourth Doctor television story “Image of the Fendahl” also involves archaeologists and physicists cooperating on a machine to view the past. However the motivations of the project are never really made clear in this case, and it is soon coopted by an ancient alien evil, so historians never really get involved. [Return to text]

[3] "Assignment: Earth" was made well before the concept of the temporal Prime Directive was introduced to limit deliberate time travel in the Star Trek universe. And before Kirk was memorably described as a "menace" by the Federation's time policing agency. [Return to text]

All opinions and viewpoints expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the University of Warwick. All images sourced from public webpages online and used here for commentary and criticism.