IER News & blogs

What might happen to Apprenticeships in England during the Covid-19 economic downturn? Blog by Terence Hogarth and Lynn Gambin*

Are apprenticeships in peril?

Apprentices are employees of the companies that train them. It stands to reason that if employment falls then the number of apprentices will fall. But looking back to the 2008 economic crisis, it is apparent that the number of apprentices actually increased, in large measure due to the apprenticeship programme expanding its occupational coverage. This time around it looks as if apprenticeships will have little fertile ground to feed any further expansion. Other things being equal it seems reasonable to expect the number of apprentices to show a potentially precipitous fall, at least over the short-term.

Apprentices are employees of the companies that train them. It stands to reason that if employment falls then the number of apprentices will fall. But looking back to the 2008 economic crisis, it is apparent that the number of apprentices actually increased, in large measure due to the apprenticeship programme expanding its occupational coverage. This time around it looks as if apprenticeships will have little fertile ground to feed any further expansion. Other things being equal it seems reasonable to expect the number of apprentices to show a potentially precipitous fall, at least over the short-term.

Trends to date

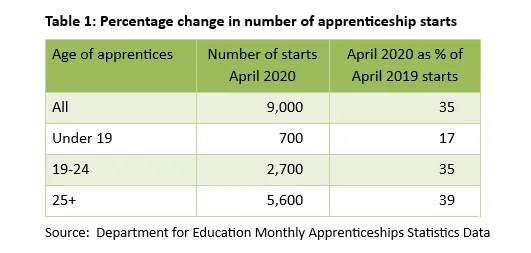

If one compares the number of apprenticeship starts in April 2019 to one year later, it is possible to gain an indication of the potential fall in the number of apprentices (see Figure 1). In April 2020, the total number of apprenticeship starts was one third of that in April 2019. Should this level of decline persist, this would indicate that 2020 will see around 200,000 fewer people starting apprenticeships than in 2019. In addition to fewer starts, there is a risk that existing apprentices might be unable to complete their training if they are made redundant.

Figure 1: Apprenticeship starts in April 2018, 2019 and 2020

Source: Department for Education Monthly Apprenticeships Statistics Data

Table 1 illustrates the uneven impact of the economic downturn on apprenticeship starts by age group. The number of starts by apprentices under 19 years of age in April 2020 was equal to 17 per cent of the level observed in April 2019. The April 2020 number of starts as a percentage of those in 2019 was 39 per cent for those aged 25 years and over, and 35 per cent for 19-24 year olds (see Table 1). While all age groups are affected, younger people appear to fare worst.

It may be that interventions of one kind or another will ensure that the fall in the number of apprentices will not be as bad as the simple extrapolations presented here suggest. Countries across Europe are hurriedly trying to find the means to prop up their apprenticeship systems. This reflects not only the urgency attached to making sure that existing apprentices complete their training, but also the need to both find places for those exiting compulsory education this year and to protect future skills supply.

Government support for VET during the crisis

On 8th July 2020 the Government announced a range of measures, supported by sizable public funding, designed to secure young people’s access to vocational education and training. These measures included:

- bonus payments to businesses in England to take on new apprentices in the next six months (£2,000 for apprentices aged 16 to 24 and £1,500 for those aged 25 and over. This bonus is on top of the current £1,000 incentive already in place for employers to take on 16 to 18 year old apprentices, and those under 25 years of age with an education, health and care plan;

- a £2 billion Kickstart Scheme in Great Britain paying the wages of 16 to 24 year old universal credit claimants to take six-month work placements;

- tripling the scale of “proven” traineeships in 2020-21 supported by £111 million of investment.

The emphasis in these announcements is on young people as their economic prospects are most at risk from the current health crisis. Whether these measures will prove sufficient and whether more intervention is required, only time will tell. But they mark a substantial intervention into the provision of training of young people by Government.

Apprenticeships the world-over are recognised as being particularly effective in helping people make the transition from school to work and, at the same time, matching the supply of skills to the needs of the labour market. It is for this very reason that policy makers have persisted with this form of training in England even though it has proved to be an uphill struggle at times to persuade employers to provide apprenticeship places.

Avoiding the mistakes of the past

If the bounce back from the recession is relatively rapid, then all that may be required is short-term assistance to ensure that a sufficiently large number of apprenticeship places are available. A wage subsidy may be one means by which this can be achieved. But if the recession proves to be more protracted, then a more root and branch review of vocational education and training may be required. No apprenticeship system worth the name can withstand year-on-year calamitous falls in the number of apprentices. It may be that T-Levels can pick up the slack. The combination of classroom based training allied to a substantial amount of time spent practising skills in the workplace potentially provides a credible alternative to apprenticeships, especially when relatively few of the latter are available.

A more damaging outcome, should any recession prove protracted, could result from ad hoc policy-making. If a cohort, or successive cohorts, of young people are funnelled into makeshift training programmes in order to avoid levels of youth unemployment last seen in the 1980s and 1990s, or even higher, then nothing will have been learnt from the policy mistakes associated with the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) and Youth Training Scheme (YTS). The failings of these programmes to deliver training which conferred economic value on their participants led to the establishment of the publicly funded apprenticeship programme in England in 1994.

A more damaging outcome, should any recession prove protracted, could result from ad hoc policy-making. If a cohort, or successive cohorts, of young people are funnelled into makeshift training programmes in order to avoid levels of youth unemployment last seen in the 1980s and 1990s, or even higher, then nothing will have been learnt from the policy mistakes associated with the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) and Youth Training Scheme (YTS). The failings of these programmes to deliver training which conferred economic value on their participants led to the establishment of the publicly funded apprenticeship programme in England in 1994.

It would be a pity to make the mistakes of the past once again by resorting to ad hoc policy responses which have a whiff of YOPS/YTS about them. There is a need to maintain access to high quality structured training opportunities so that the current cohort of would-be apprentices are not disadvantaged compared with their counterparts in the past or their likely ones in the future. This is why public support for programmes which provide high quality training opportunities, be it through apprenticeships, T-levels, or something else, is so important at the current point in time. It will not only safeguard young people’s futures, but also the future skill needs of the economy.

* Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Memorial University Newfoundland, St Johns, Canada

Interested in Terence Hogarth’s expert comment on the Kickstart scheme for 16-24 year olds? Read more here.

Interested in other blogs? Read more here

Job growth and job quality: Harnessing the potential of the Social Economy in the post-Covid recovery - Blog by Peter Dickinson

Social economy enterprises (SEEs) – such as cooperatives and social enterprises – comprise around 7% of UK employment. A recent study published by the Institute for Employment Research (IER) found that SEEs weathered the storm of the 2008 Financial crisis better than other enterprises and were able to deliver inclusive growth, sustainable development and higher quality jobs. Moreover SEEs in Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the UK provided faster jobs growth compared to other organisations. The resilience and jobs growth of SEEs in the wake of the 2008 Financial crisis should therefore be harnessed to support the current pandemic economic recovery.

The impact of the 2008 Financial Crisis

The 2008 Financial Crisis created the deepest UK recession since World War II, and the longest for more than a century according to the Office for National Statistics. UK Gross Domestic Product (GDP) did not reach pre-recession levels until 2013. Employment only recovered in 2014.

There were similar impacts across Europe with the severity and length of impact varying between countries. Southern European countries (such as Spain and Italy) fared worse whilst Northern and Eastern European countries (for example, Sweden and Poland) improved more quickly.

Compared to 2007/08, Sweden’s GDP had recovered by 2010, Poland’s by 2011, the UK’s by 2013, Italy’s by 2016, and Spain’s by 2017. Employment levels took longer to resurface: the UK and Poland reached pre-recession rates by 2014, Sweden by 2015, Italy by 2018, and Spain’s has yet to fully recover according to data from Eurostat.

Whilst the UK’s jobs rebound was relatively swift it was also problematic. As the UK’s 2017 Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices reported, the jobs recovery from the Financial Crisis led to more atypical and precarious employment, especially amongst disadvantaged groups of people, and was also characterised by slow wage growth.

The full extent of the Covid-19 induced recession is yet to materialise and so the impact on economic growth and jobs is harder to calculate. Most analysts expect a much sharper recession but a swifter recovery compared with 2008. The latest analysis by HM Treasury suggests a 25% reduction in GDP to midyear, then positive GDP growth from the autumn onwards. The jobs trend is more difficult to predict. In the countries cited above, the jobs lag compared to GDP (in terms of regaining pre-recession levels) varied from one year in the case of the UK to five years in Sweden.

The full extent of the Covid-19 induced recession is yet to materialise and so the impact on economic growth and jobs is harder to calculate. Most analysts expect a much sharper recession but a swifter recovery compared with 2008. The latest analysis by HM Treasury suggests a 25% reduction in GDP to midyear, then positive GDP growth from the autumn onwards. The jobs trend is more difficult to predict. In the countries cited above, the jobs lag compared to GDP (in terms of regaining pre-recession levels) varied from one year in the case of the UK to five years in Sweden.

What is more certain is that the impact of the pandemic will not be equal across the working population. The Institute for Fiscal Studies predicts the greatest impact to fall on the most disadvantaged groups in the economy: those on low incomes; young people; Black and Minority Ethnic workers; and women.

SEEs and recovery in selected countries

The response of the SEE sector to the 2008 Financial crisis provides evidence that jobs growth and job quality can both be achieved. Employment growth can be gained alongside inclusive growth and quality jobs benefitting employers, workers, disadvantaged people, their communities and the national economy.

The size and structure of the SEE varies across the five countries in the study. SEE employment accounts for around 17% of jobs in Italy, 12% in Sweden, 9% in Spain, 7% in the UK and 6% in Poland. The sectoral distribution also varies. In Poland, Spain and Sweden, most co-operative jobs are in agriculture but in Italy they are in health and social work, and in the UK it is banking (thanks to building societies).

The size and structure of the SEE varies across the five countries in the study. SEE employment accounts for around 17% of jobs in Italy, 12% in Sweden, 9% in Spain, 7% in the UK and 6% in Poland. The sectoral distribution also varies. In Poland, Spain and Sweden, most co-operative jobs are in agriculture but in Italy they are in health and social work, and in the UK it is banking (thanks to building societies).

Whilst the SEE sector varies there has been a consistent pattern across the countries in terms of jobs growth and business performance. SEEs recovered from the 2008 Financial crisis better than mainstream businesses and demonstrated higher growth rates. In Italy, SEEs recorded jobs growth between 2007-11 whilst employment levels elsewhere declined. In the UK, the number of SEEs increased whereas the number of mainstream enterprises fell. In Spain, SEE employment levels reached pre-recession levels by 2016 whereas they have yet to recover in the economy overall. The survival rate of Spanish SEEs was also higher compared to mainstream businesses.

The enhanced business and employment performance of SEEs has been achieved along with providing good quality jobs. Job quality tends to be higher in SEEs, for example, they employ higher proportions of permanent and full-time workers. SEEs are also more likely to be run by and employ women, as well as employing more disadvantaged groups such as disabled people and migrants.

The relative expansion of SEEs, we found in the study, was due to their business performance. Put simply they were better run businesses. They were more innovative, more effective at meeting market and customer needs, and were better managed.

Key practices, inherent to SEEs, contributed to their better management and business performance: governance and internal decision-making structures and processes; reinvesting (rather than extracting) surplus value; prioritising jobs over wages and profit; sharing risks and rewards; and a long-term focus and shared values among members and workers.

Key practices, inherent to SEEs, contributed to their better management and business performance: governance and internal decision-making structures and processes; reinvesting (rather than extracting) surplus value; prioritising jobs over wages and profit; sharing risks and rewards; and a long-term focus and shared values among members and workers.

SEEs demonstrate human resource practices more widely viewed as underpinning high performance businesses more generally, such as: effective communication structures; generating employee engagement; better skills utilisation; greater worker task discretion; employee involvement in task-related decision-making; and investing in workforce skills. These practices appear to create a ‘virtuous circle’ by which internal practice generates positive organisational performance that, in turn, provides positive employment outcomes, thus reinforcing the practice.

Supporting SEEs to deliver job growth

There is every reason to believe that SEEs can be an important component of the Covid-19 recovery. This possibility is recognised by the OECD and European Commission. The UK Government should therefore be encouraging SEEs as a route to rebuilding the economy and good jobs. In our study, we identified policy pointers to support SEEs, many of which are relevant to the current situation:

- Provide general policy support from Government, LEPs and Combined Authorities, as well as targeted specific support, such as, start-up and business support relevant to SEEs;

- Raise the profile of SEEs amongst business support organisations, and encourage SEE to take-up business support (e.g. via Growth Hubs);

- Promote social value clauses in public tendering so that cost is not the only factor when awarding contracts;

- Mainstream SEEs in enterprise and business education so that budding entrepreneurs are aware of these business models;

- Further support the development of management skills across the sector.

Through supporting and promoting SEEs, local and regional agencies can maximise the benefits of more and better quality jobs, and inclusive economic development. They can help the UK economy be built back quicker and better.

Keep up the good work – planning a way out of the Covid-driven jobs crisis - Blog by Chris Warhurst

Not even out of the health crisis, the UK is entering a jobs crisis. New data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows a mixed picture of employment but with strong indications that employment is set to fall. The UK Government has done well to maintain employment levels to date but needs to be equally brave going forward and stick to its plan to create more good jobs in the UK.

Not even out of the health crisis, the UK is entering a jobs crisis. New data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows a mixed picture of employment but with strong indications that employment is set to fall. The UK Government has done well to maintain employment levels to date but needs to be equally brave going forward and stick to its plan to create more good jobs in the UK.

The looming jobs crisis

The new data shows a slight fall in employment but likewise a slight fall in the number of workers unemployed compared to March. As the ONS suggests, that unemployment has flat lined whilst massive redundancies have been announced is surprising. One explanation, the ONS suggests, is that workers losing their jobs are becoming economically inactive i.e. they are not registering as unemployed and they are not looking for work. There may be good reasons. The number of workers starting new jobs has fallen sharply. Moreover for those workers out of work, getting back in is becoming tougher. The number of job vacancies has fallen to its lowest level in the UK for nearly 20 years.

Meanwhile since the ONS data was collected, the situation is worsening. As the lockdown eases, business is now picking up in the manufacturing and construction sectors. However employment in these sectors is falling. In addition, July has seen almost daily announcements of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of employees being laid off or about to be laid off by their companies in services such as retail.

The Chancellor Rishi Sunak acted swiftly to protect jobs as the Covid-19 crisis hit. His main strategy has been to keep the past in place. And with some success. Whilst there were problems with both, the Job Retention Scheme and Self-Employment Income Support Scheme have helped many workers retain their jobs and at least some of their income. But as those schemes are wound down and the lockdown eases firms are now starting to lay off previously furloughed employees. Moreover the self-employed struggle to find sufficient business amongst cautious consumers. Unemployment is likely to rise higher.

What should government do?

Addressing this problem by creating jobs will be important. Traditional industries such as construction and new ‘green’ industries will benefit from government-funded infrastructure projects. The government should also address the chronic labour shortages in health and social care. It can do so directly by increasing direct funding for the NHS and indirectly to care homes through increasing funding to local councils.

Addressing this problem by creating jobs will be important. Traditional industries such as construction and new ‘green’ industries will benefit from government-funded infrastructure projects. The government should also address the chronic labour shortages in health and social care. It can do so directly by increasing direct funding for the NHS and indirectly to care homes through increasing funding to local councils.

The temptation will be to create any jobs rather than good jobs. Such a strategy would be a mistake. It was a strategy adopted in the UK in the 1980s and led to foreign investors building ‘screwdriver plants’, assembling parts built elsewhere in the world. Unemployment went down but driven by too many low skilled, low wage jobs. Working poverty was one outcome. Dissatisfied voters in northern British towns and cities was another. Moreover as government inducements dried up, these plants moved on looking for other governments’ support. In the 1990s Scotland had a hub of microelectronics firms, building cash point machines for the world for example. Now, no-one talks about Silicon Glen in Scotland; the companies have largely gone even though microelectronics is still big business.

The outcome, as my IER colleagues Terence Hogarth and Jeisson Rubio-Cardenas have pointed out, is that the UK now has proportionally less jobs in medium to high-tech manufacturing than the rest of Europe. And over the past twenty years the UK labour market has steadily polarised into lovely and lousy jobs, as Maarten Goos and Alan Manning of the LSE once expressed it. As John Hurley and his team in Dublin discovered, some countries in Europe, such as Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, have generally improved the overall quality of jobs in their labour markets, creating more of the lovely jobs.

The outcome, as my IER colleagues Terence Hogarth and Jeisson Rubio-Cardenas have pointed out, is that the UK now has proportionally less jobs in medium to high-tech manufacturing than the rest of Europe. And over the past twenty years the UK labour market has steadily polarised into lovely and lousy jobs, as Maarten Goos and Alan Manning of the LSE once expressed it. As John Hurley and his team in Dublin discovered, some countries in Europe, such as Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, have generally improved the overall quality of jobs in their labour markets, creating more of the lovely jobs.

The temptation to create any jobs at any cost must therefore avoided. Instead the UK Government must stick to its pre-Covid plan to create more good jobs. Of course there is a moral case for creating jobs that pay a real living wage and enable families to lead decent lives or enable workers to fully use the skills that they have acquired through investment in education and training.

Keep the focus on creating good work

Perhaps just as importantly for an economy that needs to recover and re-expand, there is a business case for creating more good work: good work helps companies be more productive and more innovative.

In a recent initial analysis for the Carnegie UK Trust, a team of researchers at IER – Derek Bosworth, Sudipa Sarkar, Wil Hunt and myself – found that good work and productivity are positively correlated. Five of the seven dimensions used to measure good work are positively associated with productivity in the UK: pay; job design, social support in work, worker voice and representation, and work-life balance. As such, better job quality is linked to higher productivity. Importantly productivity gains do not just occur for companies offering the best quality jobs but also for those offering decent quality jobs.

In a recent initial analysis for the Carnegie UK Trust, a team of researchers at IER – Derek Bosworth, Sudipa Sarkar, Wil Hunt and myself – found that good work and productivity are positively correlated. Five of the seven dimensions used to measure good work are positively associated with productivity in the UK: pay; job design, social support in work, worker voice and representation, and work-life balance. As such, better job quality is linked to higher productivity. Importantly productivity gains do not just occur for companies offering the best quality jobs but also for those offering decent quality jobs.

Similarly, another team from IER that includes Sally Wright and myself have been working with colleagues from across Europe to examine the relationship between innovation and good work. Analysing data for 32 European countries, including the UK, our Spanish colleagues led by Rafa Muñoz de Bustillo found that product, process and organisational innovations within companies are associated with higher job quality. In other words more innovations occur in companies with better quality jobs. More innovation can help companies be more productive and, in the long run, innovation creates jobs.

The lesson? Keep up the good work

Scotland is being brave. Its government has absorbed the lessons from past economic crises. This time around it recognises the importance of job quality to the country’s social and economic wellbeing. Early in the Covid-19 crisis it announced that it was sticking to its policy of fair work – its version of good work. It is applying the principles of fair work through the crisis and beyond. It wants a better Scotland in the future and believes fair work has to be part of the strategy.

If it wants to address the impending jobs crisis, the UK Government should likewise keep to its plan to create more good work. It needs to look at the evidence. Good work can help companies be more competitive, improve employees’ quality of working life, level up the regions damaged by previous economic recessions and help the government build back better.

A tale of two job vacancies: waitering and nursing - blog by Jeisson Cardenas Rubio, Chris Warhurst and Sally-Anne Barnes

New labour market data released by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that the small rise in unemployment recorded in May has held. Unemployment has not yet risen because of the furloughing scheme. However, the collapse in job vacancies is being taken as a marker of the massive unemployment to come. The aggregate vacancy data masks some significant variations by occupation. Experimental data analysis by the Warwick Institute for Employment Research (IER) reveals falling and increasing demand for different jobs in the UK labour market.

New labour market data released by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that the small rise in unemployment recorded in May has held. Unemployment has not yet risen because of the furloughing scheme. However, the collapse in job vacancies is being taken as a marker of the massive unemployment to come. The aggregate vacancy data masks some significant variations by occupation. Experimental data analysis by the Warwick Institute for Employment Research (IER) reveals falling and increasing demand for different jobs in the UK labour market.

ONS data show falling overall vacancy figures

Data from the ONS in May showed a precipitous drop in job vacancies. Compared to previous quarterly data there was a drop of 170,000 or over 20% in job vacancies in the UK. This drop continues in the new data. It reveals that the drop in advertised job vacancies is the largest quarterly fall on record. From March to May this year, 340,00 fewer jobs were advertised than in the previous quarter. The number of vacancies might now even be a record low.

The ONS data reveals that the retail and hospitality sectors are a particular problem. However, the headline data masks significant variations by occupation. Understanding which jobs are less available and which, if any, offer opportunities is important for people facing unemployment or about to leave school, college or university this summer.

Piloting a new online job-scraping tool

As part of extending the data available in its labour market information project – LMI for All – the team at IER is currently piloting a new web scraping technique to collect UK vacancy data. LMI for All brings together different sources of labour market data to support careers advice. It is used by government, careers organisations and schools across the UK and is increasingly influential internationally. The team’s current task is to develop a method to apply the constant stream of updated vacancies to the UK occupational classification system. This data will enable the creation of trend data to analyse real-time labour demand in the UK. Web scraping consists of a computerised method to automatically collect information from across the Internet (e.g. job portals). For the LMI for All pilot, the vacancy information was scraped daily from two of the significant job portals in the UK: The Guardian and Reed, and from February 2019 to date. These two job portals are significant because they receive a high number of visits per day and include lots of information about the jobs being advertised.

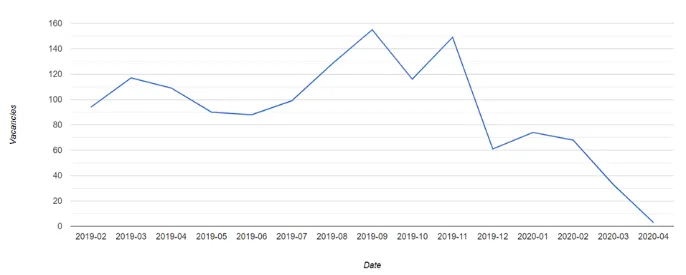

Steep fall in vacancies for waiters/waitresses

The data shows some very bad news for some occupations. The obvious example is waitering jobs. Vacancies for these jobs have collapsed during the Covid-19 crisis, as we show below Graph 1 indicates the number of job vacancies posted online (y axis) from February 2019 to April 2020 (x axis).

Graph 1: Trends in job vacancies for waiters/waitresses in the UK

Source: authors’ own data

This stark decline in vacancies for waitering jobs is not a surprise. The hospitality industry has been mothballed during the Covid-19 crisis, with restaurants and hotels closed for business. It is likely that full reopening will be difficult for companies in this industry. Restaurant and hotels will likely operate below capacity. Unfortunately, furloughing just hides looming unemployment for many workers in this industry. Indicatively, the Restaurant Group, which owns Italian American style restaurant chain Frankie and Benny's, announced the closure of 125 restaurants in June with up to 300 job losses. More similar announcements are likely.

In the UK context, these jobs tend to have low job quality as indicated by pay (not untypically minimum wage) and formal skill levels. They can be good jobs, however, in terms of providing people with entry routes into work and for students needing to pay their way through study. They have a socially useful function therefore beyond helping feed customers.

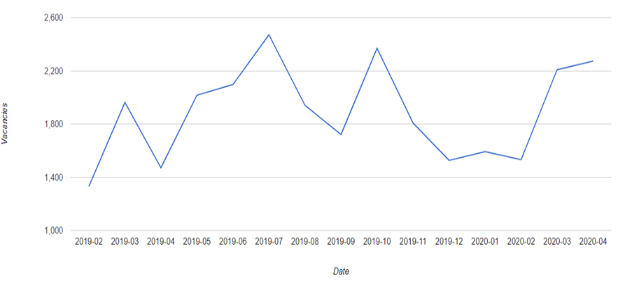

Increased demand for nurses

There is some good news. Other jobs show a step rise in job vacancies. The obvious example is nursing. Not surprisingly given the health crisis, nurses are in big demand, with a steep rise recently in the number of job vacancies, as we show below. Graph 2 indicates the number of job vacancies posted online (y axis) from February 2019 to April 2020 (x axis).

Graph 2: Trends in job vacancies for nurses in the UK

Source: authors’ own data

Nursing jobs tend to be good jobs – at least as measured by skill level. Many also offer career progression even if there are inequities in pay. The problem is that even before the Covid-19 crisis, the UK’s health service was struggling to fill its nursing vacancies. This problem is global. Worldwide there is a shortage of six million nurses. A further one million nurses are needed in Europe alone. In the UK, the Government urgently needs to rethink its workforce planning and delivery for nurses if the country’s shortfall is to be addressed. Given the likely global labour market competition for new nurses, one option would be to focus on retaining older existing nurses. Currently, too many leave the NHS from the age of 50. Understanding why they leave and what would make them stay is now imperative.

Nursing jobs tend to be good jobs – at least as measured by skill level. Many also offer career progression even if there are inequities in pay. The problem is that even before the Covid-19 crisis, the UK’s health service was struggling to fill its nursing vacancies. This problem is global. Worldwide there is a shortage of six million nurses. A further one million nurses are needed in Europe alone. In the UK, the Government urgently needs to rethink its workforce planning and delivery for nurses if the country’s shortfall is to be addressed. Given the likely global labour market competition for new nurses, one option would be to focus on retaining older existing nurses. Currently, too many leave the NHS from the age of 50. Understanding why they leave and what would make them stay is now imperative.

Knowing where the jobs are and aren’t will be important

More broadly, this vacancy data shows that the shape of the UK workforce is likely to change, at least in the short-term. The impact of the Covid-19 crisis on jobs will not be even. The stock, or volume, of some jobs will decline, others will increase. To capture these changes, IER is creating a dataset that provides key insights into the UK labour market. In real time, we will be able to analyse demand for particular occupations and the skills needed within these occupations. As the UK economy contracts over the year, identifying where the job opportunities exist will be vital, not just for career advisers and those working in job centres but also for the unemployed as they retrain or new entrants as they come on to the labour market looking for jobs.

Towards a national database of the informal sector: pandemic response and future recommendations for Indonesia - Blog by Joanna Octavia

After only a few months, the global Coronavirus pandemic has affected workers worldwide in a profound way. Strict social distancing and lockdown measures around the world have halted daily activities, presenting a threat to the livelihoods of billions of workers who rely on their daily earnings in the informal sector.

After only a few months, the global Coronavirus pandemic has affected workers worldwide in a profound way. Strict social distancing and lockdown measures around the world have halted daily activities, presenting a threat to the livelihoods of billions of workers who rely on their daily earnings in the informal sector.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that almost 1.6 billion informal workers or nearly half of the global workforce are significantly affected by pandemic measures.

In Indonesia, 55% of the workforce or around 70 million people work in the informal sector. Unregistered, unregulated and unprotected by secure employment contracts and social safety nets, informal workers are some of the most vulnerable in the labour market.

Who are the informal workers in Indonesia and what support is available to them?

Informal workers in Indonesia are spread across sectors and occupations, including but not limited to construction, street vending, domestic work, and motorcycle taxi driving. Following the pandemic outbreak, a majority of these workers are at risk of losing their livelihoods as a result of their insecure working conditions. GARDA, an Indonesian organisation for online motorcycle taxi drivers, noted that their incomes have fallen by 80% due to the pandemic.

Furthermore, salaried informal workers such as domestic workers and those employed “off the books” by businesses face the possibility of being asked to stop coming to work with the risk of receiving no compensation for their termination. Different to formal sector workers, informal working arrangements are not subject to the national labour legislation, social protection, or entitlement to certain employment benefits, such as advance notice of dismissal and severance pay.

Whilst the Indonesian Government has deployed a range of social assistance benefits to help Indonesians weather through the crisis, informal workers are lumped together with the poor and very poor. However, many informal workers earned just enough before the pandemic and will not be able to benefit from assistance programmes that target households with little to no earning potential. Some informal workers also own assets, which may exclude them from social assistance for the poor and very poor.

Moreover, studies on informality in Indonesia suggest that a large proportion of those working in the urban informal sector are economic migrants. One repercussion of always constantly being on the move is the possibility of not being documented by the local administrative office, which maintains the data of potential assistance beneficiaries within their locality.

Moreover, studies on informality in Indonesia suggest that a large proportion of those working in the urban informal sector are economic migrants. One repercussion of always constantly being on the move is the possibility of not being documented by the local administrative office, which maintains the data of potential assistance beneficiaries within their locality.

The limited information we have on the informal sector has resulted in a plethora of problems during this pandemic, in particular when addressing questions such as: (1) who are the informal workers?, (2) where do they work?, and lastly (3) how do we reach them in a way that is more systematic and effective?

What needs to be done in the short-term?

In the short term, the government must track and measure how vulnerable groups of workers are being impacted. This means taking active steps to cross-check data between agencies, offices and initiatives to develop a national database of informal workers. The data collected should include not only identification details, work history and financial conditions but they should also contain information on occupation and working arrangement.

-

Targeted support measures: The data could be used to design and implement support measures tailored to the conditions of informal workers. In addition to the assistance offered by government, donations from individuals or civil society groups could then be effectively allocated and distributed to them if such data is made available.

-

Redeployment into in-demand roles: Another way that the data can be used is to redeploy informal workers. While some industries are disrupted as a result of the pandemic, some, such as medical services, ecommerce and logistics, are growing. There is opportunity to retrain workers of all levels for the available jobs or reskill them to meet evolving market needs. Both the government and private sector, including social enterprises, should engage grassroot organisations to explore these possibilities.

What can be done in the longer term to support informal workers?

In the longer term, the pandemic highlights the urgent need for government to protect those operating and working in the informal sector through regulatory change. Workers may choose to stay informal for many reasons but the persistence of the sector indicates that it should not be considered as a stopgap measure.

In the longer term, the pandemic highlights the urgent need for government to protect those operating and working in the informal sector through regulatory change. Workers may choose to stay informal for many reasons but the persistence of the sector indicates that it should not be considered as a stopgap measure.

- State recognition: The governing Law on Manpower No. 13 of 2003 does not recognise informal workers, including own-account workers and workers without formal working arrangements, specifying workers as only those who possess a formal working relationship with an employer.

Furthermore, to ensure that the Law on Manpower is extended to all workers, there needs to be a recognition of the different types of informal workers by their working arrangements or employment relationship in order to clarify the obligations that each stakeholder has towards the worker in the law.

-

Consideration of new forms of work: Regulations that correspond to the changing landscape of employment relations in Indonesia should be considered. The role of digital platforms as a mediator between customers and own-account workers extends beyond the relationship between employers and workers as defined in the Law on Manpower.

Given that workers attach different levels of importance to the work that they do in the informal sector, and that informal work is experienced differently across platforms, it is imperative that the government designs supporting regulations that would not only protect workers but also provide business certainty for the customers and respect the flexibility enabled by some platforms.

Given that workers attach different levels of importance to the work that they do in the informal sector, and that informal work is experienced differently across platforms, it is imperative that the government designs supporting regulations that would not only protect workers but also provide business certainty for the customers and respect the flexibility enabled by some platforms.

-

Cohesive workforce development map: Lastly, it should be remembered that the urban informal sector in Indonesia does not exist in a vacuum. Other factors, including efforts to upskill and reskill, jobs mismatch, digital divide and poor infrastructure in other parts of the country, need to also be taken into account when designing a workforce development roadmap.

Governments at both the national and regional levels should consider growing economic centres outside of Indonesia’s large cities and explore other growth opportunities to narrow the regional divide.

Joanna is also a Visiting Fellow at CSIS (Centre for Strategic and International Studies)Indonesia. The original commentary is downloadable from the CSIS website here.