Productivity and the Futures of Work GRP Essay Competition 2021 - Runner Ups

Congratulations to all our 2021 Essay Competition Runners up!

Runners Up Postgraduate category

- Jeff Slater (MBA student, Warwick Business School)

- Aniqa Hussain (MSc student, Department of Psychology)

Runners up Undergraduate category

- Xaymaca Awoyungbo (History)

Xaymaca Awoyungbo - Runner Up

What did the perfect day look like in the different stages of the pandemic? What does it mean for future productivity at work?

I love definitions. They are important because they provide us with clarity, especially in written forms of communication. If I am unfamiliar with a word I search for its significance. Even if I have seen it before, sometimes I want to find out what it really means. So, I think it is important to highlight three keywords in this essay’s title.

Pandemic, productivity and perfect. One thing I love more than definitions is alliteration. All three ps are words we should be familiar with but over the last 18 months they have taken on a new meaning.

Pandemic

Pandemic was the word of 2020. According to various Internet sources, it can be defined as: the rapid spread of an infectious disease over multiple continents or the world. Having said that, over the last year, the meaning of the word was ever-changing.

Initially, it meant panic. Panic; sudden uncontrollable fear or anxiety, often causing wildly unthinking behaviour. I remember the public frenzy to purchase products, from loo roll to pasta. I remember conspiracy theories about the ‘real’ reasons for COVID-19 and national lockdowns. I remember looking to my prime minister, professors and peers for guidance on how to behave - at times they were equally clueless.

Although I rejoiced at the positives, like the cancellation of A level exams, everyone involved in education found themselves in an awkward position.

As a student, I found myself parodying Hamlet in my own stress induced soliloquy, questioning whether to work or not to work. Teachers gave us incentives to do the former, arguing that work done during lockdown could somehow contribute to our overall marks. However, in reality, not even the Secretary of State for Education could find a fair way to grade us.

So, in the primary stage of pandemic panic, a perfect day looked like my computer screen as I undertook a new hobby: video editing. It smelt like fresh sweat, after I had finished my other new hobby: home workouts. Moreover, it tasted like banana cake as a result of my third new hobby: baking.

Yet crucially, it sounded like my form tutor asking if I was completing the work set by subject teachers (initially I did complete some of the work half-heartedly). But it felt like freedom from the restraints of formal education. I started to enjoy the release I felt when I exercised my curiosity and did the work I wanted to do.

Productivity

Productivity; the effectiveness of productive effort, especially in industry, as measured in terms of the rate per output per unit of input.

Even prior to the pandemic, productivity was a word bandied about, especially in the business world. However, in our new world, the meaning of productivity could be interpreted differently.

Firstly, the majority of us were working from home. Zooming to work was replaced by video calls on Zoom. In addition, offices were replaced by unofficial workspaces, like bedrooms, living rooms and sheds. So, as the initial pandemic panic died down and lockdowns became the norm, the distinction between work and life, became increasingly blurred.

On the one hand, it was beneficial. I thrived working from my room, since it is my own carefully curated space. A perfect day here looked like a balance between work and play. As I had no obligations as an A level student by the summer of 2020, I genuinely found the work I completed enjoyable.

I slotted into my own routine. Waking up at 7:30 and sleeping at 11:00. I spent most days exercising, practising my new hobbies and taking time out to relax. There was less pressure than usual, thanks to the absence of exams and the gradual lessening of restrictions, so I chose how I wanted to work.

On the other hand, work and life coexisting in the same space, created difficulties regarding toxic productivity.

As lockdown extended, I felt as though I had to work to ‘make the most of my time’ in temporary isolation. I had to be doing something all of the time, or else I was wasting precious hours. Despite the fact that 2020 was a time when people experienced restrictions on what they were able to do, it somehow caused an obsession with work precisely because there was little else to do.

After days of pushing myself to the limit, sometimes writing, publishing and promoting three articles a week on my blog (another lockdown pastime), I questioned the point of all this productivity. Am I being productive for productivity’s sake? Am I appreciating this time I value so dearly? Now that I have more time in the day to do as I wish, why am I rushing to complete every task on my list?

Perfect

Notice, I have already used the word perfect, when describing days during the panic stage of the pandemic along with the easing of restrictions in summer. It is probably the word most familiar to us but ideas of perfectness can be problematic.

Perfect; having all the required or desirable elements, qualities or characteristics; as good as it is possible to be. The pandemic was therefore far from perfect. Nonetheless, up until 2021, it seemed I was trying my best to reach perfection – an impossible task, which caused unnecessary stress. But, they do say hindsight is 2020.

A ‘perfect’ day during the first term of university can be broken down into thirds. In the first third, I spent hours reading and watching material in preparation for my seminars. In the second third, I dedicated time to socialising and engaging with the various societies I joined; from football to African Caribbean Society to student radio. In the last third, I endeavoured to maintain my previously picked up lockdown hobbies, like piano playing and blog writing. They were all noble endeavours and I tried my best to complete all my tasks every day but eventually something had to give.

I recall telephoning my parents, describing the myriad of incredible things I was doing or that I was about to do. On many days events clashed, causing me to discuss the best course of action, until one day my father asked me, ‘son, when do you rest?’ I was so caught up in ‘doing things’ that I had forgotten to take time out to ‘do nothing’. I was so desperate for the complete ‘uni experience’ that in all honesty was not possible, given the circumstances.

Consequently, in 2021, I no longer strive for perfection, instead I try to do what is possible. Another p, meaning able to be done or achieved. That does not suggest that I have to limit myself however. Far from it.

The pandemic has forced many of us to better utilise our resources. For instance, I recorded a documentary from home, simply using Zoom, a camera and my imagination. My tutors pushed themselves to conduct seminars online, albeit sometimes struggling to work the share screen button or breakout rooms. The university culture itself changed as more of us thought of creative ways to learn and socialise online, with Spanish practice on Microsoft Teams and games nights on Google Hangouts.

So, as we edge closer to a world in which COVID-19 becomes a manageable disease, one word sticks out to me. Redefine. Defined as: ‘define again or differently’, it is a word that is fitting, given all the change we have experienced over the last 18 months. The pandemic accentuated the problem with the way in which some of us define work. The idea that work is a part of us and it becomes our sole purpose. It is an idea I understand if you are fortunate enough to love your work, but for many of us a barrier between work and life is required. It is healthy and we should be educated about it.

At school they teach you the three rs (although only one of the words starts with r): reading, writing and arithmetic. Coined around three hundred years ago, I think it is time for a redefine this phrase and apply it to the world of work and higher education. My three rs are: right (whatever work is appropriate for you), work (execution of said work) and rest (time taken out to relax).

Jeff Slater - Runner Up

Introduction

During the Covid-19 pandemic, my personal situation has changed significantly. At the start of 2020, I was working full-time in a job that involved working 5 days in the office. I lived in a flat that I shared with an old schoolfriend and worshipped at a church that met nearby. My social life was full, with plenty of friends and family nearby that I would see frequently.

Within a year, I would leave my job. I would move back in with my parents. I would start full-time study at Warwick Business School (WBS). There would be national lockdowns, new regulations and a complete change of lifestyle.

In this essay, I will share some of my experiences from different stages of the pandemic. Personal lessons learned will be explored, with suggested advice for future productivity.

Stage 1: As an Employee

When ‘Lockdown 1’ came into force in March 2020, I was sharing a flat with an old schoolmate. A friend of ours came to visit – as he thought – for a couple of days. Three months later, he was able to move out.

The change in our living situation reflected impacts felt across the world. Parents had students return home for extended periods. Families adjusted to having parents work at the kitchen table.

I continued to work for my employer, but in a fully remote, virtual way. My team had a daily morning video call on Microsoft Teams, which once a week included a fun game or activity – such a quiz or singalong – to lift our spirits and get us ready for the weekend. Before lockdown, ours had been a chatty, lively work environment. These team calls reminded us that we were connected and provided a lifeline for emotional support from colleagues.

My new ‘office’ comprised a flat-pack IKEA desk in the corner of my bedroom. (I normally tilted my camera angle so as not to show my bed in the background on video calls.) This presented a challenge to delineate between my work and rest environments. Very early in the lockdown I established the habit of clearing away my laptop and equipment at the end of the workday. They would go in a bag, under the desk and out of sight when my work was done.

The lockdown meant working longer hours, but I did not mind. It felt positive to be productive and being busy kept my mind occupied. This was an experience shared by many who reported “higher levels of happiness and productivity” working remotely – a truly remarkable impact, considering 60% of US employees were doing so due to the pandemic, compared to 5% previously (The Economist, 2021). In fact, it is entirely possible that my less noisy workspace contributed to my being in a “flow” state, increasing my productivity and wellbeing (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989:821).

A habit that has helped me stay positive during lockdown was suggested by my manager. This was to keep a list of my achievements. Rather than being frustrated that I had not achieved as much as I wanted to, I could celebrate and enjoy my successes, however small.

In this lockdown, my employer felt the pandemic’s economic impact. Clients had slashed their budgets, reducing revenue. In the summer, I applied for voluntary redundancy, opening my mind to new possibilities. Then I applied for an MBA at WBS.

During my application, I came to realise the importance of fresh air and exercise. I had sat looking at a blank page on my laptop screen. I decided to go outside. After a walk around my local park, along with some jogging and press-ups, I wrote the essay for my application in about 40 minutes.

The exercise obviously worked. That essay formed part of my successful application for the MBA programme at WBS.

Stage 2: As a Student

In September, I started studying for my MBA. This was a significant shift for me as I had previously done an apprenticeship and had been in full-time employment for over 5 years. I was looking forward to meeting classmates, networking and enjoying face-to-face lectures.

This was fine until Term 2. While visiting my parents for the Christmas break, another lockdown was announced. Lectures would be online. I was not to travel back to my university accommodation on-campus.

It was a strange experience, studying homework in my parents’ house. Being an independent adult while juggling family relationships with a busy study routine was challenging. My family’s flexibility and patience meant a huge deal to me and reinforced the importance of support networks in times of crisis.

As well as the change in environment, learning switched to fully virtual delivery. This led to a lot of Zoom fatigue (Bailenson, 2021) (Fosslien & West Duffy, 2020). Some lectures fitted a virtual format better than others, with accounting and finance lectures proving particularly difficult late on Monday afternoons, with the encroaching winter darkness and the cumulative tiredness from days with as many as 10 hours of screen time.

By week 7 of the term, I felt as though I had hit a brick wall. My enthusiasm was ebbing, and my mental health had taken a battering. I spoke to a friend and in turn supported a fellow coursemate who was struggling. Remote human contact is still contact, and the support we can offer each other should not be underestimated.

Term 3 saw a return to a hybrid model of face-to-face and online learning. This proved emotional for many of my classmates, and the opportunity to have conversations and share struggles with peers was very encouraging. I moved back into student accommodation.

As a student, I have found that changing my working location is beneficial. Sometimes I am more productive in my kitchen, while at other times my bedroom provides the quietness I need to focus. When permitted, I often use the library or the postgraduate study space in the WBS building, with its ambient noise.

Throughout my studies, I have endeavoured to keep a healthy relationship between work and rest. I thoroughly enjoy studying but in order to maintain creativity I must be well-rested (and well fed – porridge breakfasts have played a significant role in my academic success). The system I have adopted is to try and take one day off per week, doing no work at all for a 24-hour period. This was instituted partly for religious reasons (as a Sabbath – see Comer, 2019) and has noticeably reduced my stress levels and heightened my productivity in the six working days of the week.

When I started writing this essay, I was halfway through a self-isolation period. My flatmate tested positive for coronavirus, and so for ten days I went without many of the activities that have helped my mental health during the pandemic. I could not go outside for walks or watch the ducks on their ponds at Warwick’s campus. I could no longer visit my friends’ garden for a barbecue or go to the WBS building’s shared study space.

The absence of these liberties made me appreciate them more, but also forced me to be grateful for what I had. Meditating in my room I could look out of my window, seeing and hearing the rustling leaves in the tree outside. Mindfulness enriched by an awareness of the natural world helped me to spark creativity and maintain calmness in a stressful period.

Conclusion

My experience during the Covid-19 pandemic has been varied. I have learned – as a flatmate and a friend, as an employee and a student – some valuable lessons:

- Fresh air and exercise really do help, and do improve brain function (Voss, et al., 2019:328). Increased oxygen and blood flow can boost productivity and elevate creativity.

- Humans are social beings. Even if we cannot meet people in persons face-to-face, make the most of the human contact you can have. Support others and accept help from others.

- Routine and structure are beneficial. Separating workspace from non-workspace is really important. If that is not possible then find other ways to demarcate between work time and non-work time.

- Find what works for you. Everyone has their own unique situations. Exercise what control you can over your work and home environments to best facilitate productivity and wellness. Eat well. Take breaks. Enjoy nature.

The Covid-19 pandemic has provided both challenge and opportunity. Varying circumstances mean individual experiences have been both positive and negative, sometimes changing in each stage of the pandemic with its recurring themes of unpredictability and a lack of control. A “perfect” day during the pandemic will not have looked the same for everyone.

As we move forward to a post-pandemic world, previously held assumptions about work and life have been challenged. The task for humanity is to appreciate individual differences while maximising opportunities for all. Shaping our days around our circumstances and making the best of the chances offered us will be crucial and, ultimately, rewarding, as we seek to be productive and to learn collectively from what has been a deeply unsettling period.

Bibliography

Bailenson, J. N., 2021. Nonverbal Overload: A Theoretical Argument for the Causes of Zoom Fatigue. Technology, Mind and Behavior, 2(1), p. [].

Comer, J. M., [2019]. The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry. Kindle Edition ed. s.l.:Hodder & Stoughton.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & LeFevre, J., 1989. Optimal Experience in Work and Leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), pp. 815-822.

Fosslien, L. & West Duffy, M., 2020. How to Combat Zoom Fatigue (Harvard Business Review Conversation). [Online] Available at: https://bond.edu.au/nz/files/4829/How%20to%20Combat%20Zoom%20Fatigue.pdf

[Accessed 26 June 2021].

The Economist, 2021. The rise of working from home. [Online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/special-report/2021/04/08/the-rise-of-working-from-home

[Accessed 30 June 2021].

Voss, M. W. et al., 2019. Exercise and Hippocampal Memory Systems. Trends in Cognitive Science, 23(4), pp. 318-333.

Aniqa Hussain - Runner Up

The concept of the perfect day would arguably vary dramatically from individual to individual and over the course of the pandemic. For some, it may have been showing up as a key-worker and doing the best they could, for some it may have been fighting the virus slightly better one day compared to the last and for some it may have been allowing themselves to go through the difficult process of bereavement. Personally, the concept of the perfect day redefined itself at every stage during the pandemic, and with it, the term ‘productivity’ has also redefined itself. In this essay I describe my definition of the perfect day and a productive day and how this altered during the pandemic.

Beginning

My idea of the Perfect Day: Waking up at 7AM, starting my work after breakfast, stopping for lunch at 12:30, continuing with my work until 6PM, then going for a walk.

My definition of a Productive day: Spending as much time doing something academic as possible.

Very early on, I realised that my idea of a ‘perfect day’ very closely correlated with my idea of a ‘productive day’; but this often meant that the more ‘perfect days’ I had, the more exhausted and burnt out I would feel. The Cambridge Dictionary (2021) defines productivity as “causing or providing a good result or a large amount of something”; this definition highlights that the quality of the outcome may be seen as a unit of measurement for productivity, so why did I need a whole day of relentlessly working to feel as though I had been productive? Why did I feel guilty when I finished working at 6PM when I could have continued? Why had time become my unit of measurement for productivity? An article by Sehgal and Chopra (2019) highlighted this re-definition of ‘productivity’ to be a common misconception in the work culture today.

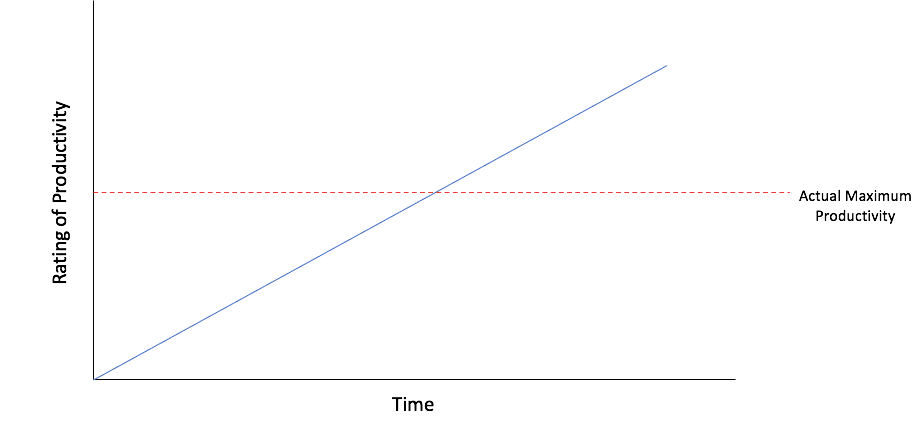

Perceived productivity over time

Note. The graph above shows how I would have rated my productivity, and how this correlated with the amount of time I spent working. It also shows where I now feel my actual maximum threshold for productivity is.

Upon evaluating what my actual maximum productivity threshold may be, I reconsidered what it was I was really rating when I thought about my productivity, as stated above, I realised that I was rating the amount of time I had spent sat down looking at my work. However, if I had spent this time looking at my work, already beyond the threshold of my maximum productivity, then this time had clearly been wasted. Research has shown that on average productivity per hour dramatically declines when an individual has worked more than 50 hours in a week. This demonstrates that more time does not necessarily equate to better work.

I also began to question why academic work was the only factor of my life that I thought working on was ‘productive’. Academia is essentially only one part of who I am; there is also my health, my mental wellbeing, my hobbies and my family and friends. Despite this, I was spending a great portion of my ‘perfect’ day on my university work. Following this revelation, I set out to re-construct my lifestyle in a way that incorporated other aspects of my life, starting with fitness and mental-wellbeing.

Now

Perfect Day: I wake up at 7, have breakfast and read a chapter of a book of my choice. I go out for a jog or walk. As I am working from home, there is still a degree of flexibility; I start my university and ensure that I finish my set goals for the day. Working no later than 5PM. After this I spend time with my friends and family, occasionally do some yoga and enjoy downtime. I now leave weekends completely free.

My definition of a Productive day: incorporating tasks and activities that allow me to perform my best while reaching my goals.

Riddle (2010) wrote an article on ‘personal productivity’, he defined it as the process of completing tasks in order to progress towards set goals, while maintaining a healthy balance in your life. In 2018 an article was published by Personnel Today, an organisation focused on workplace health and wellbeing, linking employee wellbeing to productivity. Hancock & Coopershare (2018) highlighted the UK’s lag in productivity when compared to other countries. They suggested this may be remedied through focus on employee wellbeing. However, this is only now being recognised by employers, and individuals themselves.

By adopting the ‘personal productivity’ approach to my work I was able to create a much more efficient work-life balance, which resulted in the highest grades I had achieved throughout my three years at university. Not only had the balance meant I was incorporating healthy living habits into my life such as exercise, downtime and socialising but I was also reaping the rewards of my study time; all of these combined had an incredible impact on my mental health, confidence and optimism for the future.

Going Forward

My current idea of a perfect day is one that I would like to carry with me for years to come, as I have found that it not only enables me to feel refreshed and positive in the short-term, but also enables me to reach long-term goals, in regard to health and academic progress while maintaining an active social life and opportunity for self-care. I am now able to see self-care as a form of productivity.

In regard to future productivity at work, I feel that this will lead to more efficient use of my time at work and better quality outcomes. Bubonya et al. (2017) demonstrated the association between poor mental health and higher absenteeism and presenteeism rates. This is further supported by a cross-sectional study conducted by Dyrbye et al., (2019) highlighted the negative relationship between burnout, absenteeism and job performance. Reducing job stress and promoting wellbeing were recommended to increase work productivity. For this reason, finding a healthy work-life balance will be a key concern for me going forward, and hopefully also for employers across the nation.