Our Ears on the Sky

Radio astronomy is the study of the sky at wavelengths longer than the more familiar optical light to which our eyes are sensitive. Unlike infrared or ultraviolet light, radio waves can penetrate our atmosphere, but carry very little energy and so are hard to detect. Evolving from studies of communications radio and radar in the 1940s, and involving very different technologies and requirements, radio astronomy developed in parallel with optical astronomy but remained distinct from it - with multi-wavelength astronomers, straddling the two disciplines, relatively rare before the last few decades.

While radio astronomy does not capture the public imagination in quite the same way that the midnight sky of optical astronomy does, it has nonetheless been pivotal to at least some science fiction stories over the years.

SETI and METI

Undoubtedly the most common and striking use of radio telescope equipment in science fiction is as part of the endeavour to search for and message extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI and METI, respectively).

SETI: The Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence

METI: Messaging ExtraTerrestrial Intelligences

Cosmologist and astronomy populariser Sir Fred Hoyle had a deep interest in the potential of radio astronomy to change our image of the Universe and also to inspire visions of the future, despite not being a radio astronomer himself. His extensive use of radio telescopes in science fiction tended to focus on their use for METI. His earliest venture into this field was in his first science fiction novel, The Black Cloud (Hoyle, 1959). This described a dense interstellar cloud, a Bok globule, entering the Solar System and threatening life on Earth. After an initial study of the cloud, a group of astronomers conclude that it may be intelligent and make use of a radio telescope to communicate with the diffuse but vast and ancient being.

Cosmologist and astronomy populariser Sir Fred Hoyle had a deep interest in the potential of radio astronomy to change our image of the Universe and also to inspire visions of the future, despite not being a radio astronomer himself. His extensive use of radio telescopes in science fiction tended to focus on their use for METI. His earliest venture into this field was in his first science fiction novel, The Black Cloud (Hoyle, 1959). This described a dense interstellar cloud, a Bok globule, entering the Solar System and threatening life on Earth. After an initial study of the cloud, a group of astronomers conclude that it may be intelligent and make use of a radio telescope to communicate with the diffuse but vast and ancient being.

He returned to a similar theme in a much later novel. The cover of Comet Halley (Hoyle, 1985) featured the iconic Lowell telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory (despite it only being mentioned once in the text! [1]) and the primary focus of the novel involved the use of radio frequency signals to communicate with (intelligent, living) comets [2].

Hoyle mentioned another common use of radio telescopes, as channels of contact with an Earth-launched interstellar craft rather than for observation of the stars or METI, in the novel The Fifth Planet (1953), cowritten with his son Geoffrey. This reflects the reality that many radio telescopes around the world have received funding or other support from government agencies in return for engaging in tracking of spacecraft beyond the range of conventional satellite dishes - indeed, this was one of Jodrell Bank’s first claims to fame when its 76m telescope was used for communications and tracking during the era of American and Soviet lunar missions. Down to Earth by Paul Capon (novel, 1954) has a similar subplot, in which amateur radio astronomers detect signals from a missing Earth-origin space mission which has been forced down on an alien world. Hoyle & Hoyle’s The Fifth Planet, incidentally, is the only novel I know of where an entire plot point hinges on the existence of radio side-lobes: the sensitivity of any radio antenna not only to the signal directly in front of it but also, to a lesser extent, signals from behind and to the sides. While radio telescope dishes are designed to suppress back- and side-lobes, a bright enough source can still swamp faint signals if it happens to lie in one of these regions of non-zero sensitivity.

Hoyle was also a co-creator and key influence on the development of the well-remembered early television science fiction series, A for Andromeda (BBC TV, 1961) and its sequel The Andromeda Breakthrough (BBC TV, 1962), both of which I've discussed before. These followed the personnel of a radio telescope facility (used for both science and for military satellite tracking) after they receive an alien signal. The signal in question includes instructions for the construction of an artificial human who acts as a bridge between the two species. As in many of these stories, we see relatively little evidence for what scientific research the radio telescope is intended to undertake, and the focus rapidly turns to the alien message and the created entity.

Another cosmologist, Carl Sagan, also used a radio telescope (in this case the Very Large Array in New Mexico, which was memorably used as a location for the movie version) to receive alien instructions in his novel Contact (novel, Sagan, 1985; film, 1997, dir. Zemeckis). However this time the instructions were not for an organic being but rather for a vast technological construct which enables interstellar travel. More passive (at least initially) uses of radio telescopes to intercept alien signals include John Varley’s novel The Ophiuchi Hotline (1977, in which radio astronomers detect a stream of information broadcast by aliens), and The Goldilocks Zone (a 2021 BBC radio play written by Tanika Gupta, describing radio detection of an apparently inhabited world 25 light years away).

Another cosmologist, Carl Sagan, also used a radio telescope (in this case the Very Large Array in New Mexico, which was memorably used as a location for the movie version) to receive alien instructions in his novel Contact (novel, Sagan, 1985; film, 1997, dir. Zemeckis). However this time the instructions were not for an organic being but rather for a vast technological construct which enables interstellar travel. More passive (at least initially) uses of radio telescopes to intercept alien signals include John Varley’s novel The Ophiuchi Hotline (1977, in which radio astronomers detect a stream of information broadcast by aliens), and The Goldilocks Zone (a 2021 BBC radio play written by Tanika Gupta, describing radio detection of an apparently inhabited world 25 light years away).

By contrast, blind (unfocussed) Messaging of Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) in the form of the famous message broadcast from the Arecibo radio telescope in 1974 forms the premise of Charles Chilton’s follow up to Journey Into Space, Space Force (BBC radio, 1984). In this serial, a space crew investigating unusual signals from the vicinity of Jupiter in 2010 intercept a series of broadcasts that prove to be referencing the Arecibo message, described in the show as having been broadcast thirty years before and as part of a long-abandoned METI programme. This idea - that SETI and METI programmes need to operate over a long time period and may end before a response is received - is also the main theme in James E Gunn’s short stories collected in novel form as The Listeners in 1972 [3]. The timeline here, which also uses an Arecibo setting, spans a century of scientific and social development between a message being transmitted and the reply being received.

In all of these cases, the existence of a large, sensitive radio receiver directed into space owes its origins to radio astronomy, but the story does not focus on the scientific study.

Iconic Radio Observatories

While SETI and METI are by far the most common context for radio telescopes in science fiction, the telescopes themselves have become a potent symbol of futurism and scientific advancement. I have already discussed the use of Jodrell Bank’s famous 76m Lovell Telescope as an icon of the future in a previous blog entry. Its instantly recognisable design and profile has long since been associated with both the wonders and the challenging complexity of modern scientific development, even when transplanted to alternate settings (as in the case of Doctor Who’s “Logopolis” in 1981, for example).

However other radio telescopes have also been drawn into similar roles. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico consists of twenty-seven independent radio dishes, the signals from which are combined to simulate a much larger telescope in a process known as aperture synthesis. The sight of the numerous telescopes, all turning in unison in response to an electronic signal, provides a striking imagery which was exploited to give astronomer characters authority in the film Contact and also in 2010: The Year We Made Contact (film, 1984, dir. Hyams). Another, much smaller aperture synthesis observatory served much the same role in the television serial Quatermass (aka The Quatermass Conclusion, ITV TV, 1979), although here the much smaller and less well maintained facility is also somewhat emblematic of how Professor Quatermass’s authority and influence has declined since the heyday of his earlier adventures. At first sight, the dishes and tracks look rather like those that can still be found at the venerable Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Lords Bridge near Cambridge, one of the world’s earliest radio astronomy facilities, although the landscape is inconsistent with the flat Cambridgeshire countryside and some reports suggest that the dishes seen on screen (see image above) may have been an elaborate and impressively accurate mock-up.

However other radio telescopes have also been drawn into similar roles. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico consists of twenty-seven independent radio dishes, the signals from which are combined to simulate a much larger telescope in a process known as aperture synthesis. The sight of the numerous telescopes, all turning in unison in response to an electronic signal, provides a striking imagery which was exploited to give astronomer characters authority in the film Contact and also in 2010: The Year We Made Contact (film, 1984, dir. Hyams). Another, much smaller aperture synthesis observatory served much the same role in the television serial Quatermass (aka The Quatermass Conclusion, ITV TV, 1979), although here the much smaller and less well maintained facility is also somewhat emblematic of how Professor Quatermass’s authority and influence has declined since the heyday of his earlier adventures. At first sight, the dishes and tracks look rather like those that can still be found at the venerable Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Lords Bridge near Cambridge, one of the world’s earliest radio astronomy facilities, although the landscape is inconsistent with the flat Cambridgeshire countryside and some reports suggest that the dishes seen on screen (see image above) may have been an elaborate and impressively accurate mock-up.

Moving towards the other end of the scale for radio telescopes, another observatory which has captured the public attention has been the vast Arecibo facility. Located in Puerto Rico, the Arecibo dish was a single (i.e. filled aperture) antenna, a thousand feet in diameter. Because of its size, it was fixed in position in a valley, rather than fully steerable. Its main target was the sky rotating overhead, with some directionality provided by a receiver suspended on cables overhead. The sheer size of the Arecibo dish, together with its prominence in popular culture as a result of METI efforts, has led to its prominent appearance in films such as Contact, and the James Bond science fictional thriller GoldenEye (film, 1995, dir. Campbell). In The Listeners (mentioned above), Gunn sites his METI project in the shadow of Arecibo and provides a poetic description of the large dish:

Moving towards the other end of the scale for radio telescopes, another observatory which has captured the public attention has been the vast Arecibo facility. Located in Puerto Rico, the Arecibo dish was a single (i.e. filled aperture) antenna, a thousand feet in diameter. Because of its size, it was fixed in position in a valley, rather than fully steerable. Its main target was the sky rotating overhead, with some directionality provided by a receiver suspended on cables overhead. The sheer size of the Arecibo dish, together with its prominence in popular culture as a result of METI efforts, has led to its prominent appearance in films such as Contact, and the James Bond science fictional thriller GoldenEye (film, 1995, dir. Campbell). In The Listeners (mentioned above), Gunn sites his METI project in the shadow of Arecibo and provides a poetic description of the large dish:

“... he saw below them a valley that gleamed metallic in the night. Across the valley some giant spider had been busy spinning cables in a precise mathematical pattern; it was a web to catch the stars.” (1978 UK edition, pg 104)

Unfortunately the dish was damaged beyond repair by storms, earthquakes and later by impact damage from snapped cables in the early 2010s.

Astronomy

While the telescopes themselves provide spectacular settings, and METI has an irresistible draw, relatively little science fiction actually discusses the science of radio astronomy - the study of our universe at long wavelengths - for its own sake.

Perhaps fittingly, one of the earliest references to radio astronomy that I've found appears in radio science fiction. In October 1956, radio anthology series X-Minus-One produced a dramatisation of Katherine MacLean's 1951 short story "Pictures Don't Lie", adapted by Ernest Kinoy. The narrative pivots on a scientist investigating radio static, with a focus on military communications. The adaptation is fairly loose in places, reframing the story to a first-person account, and interpolates an interesting comment from the scientist character to the journalist narrator: "I think you wrote about the work

at Bell Telephone and RCA Labs about radio telescopy mapping the star positions by static". What fascinates me about this is that the radio broadcast significantly pre-dates Bell Labs' most famous contribution to radio astronomy: the Nobel Prize winning discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation by Penzias and Wilson, using an antenna built in 1959 to support the first US communications satellite experiment. Bell Labs had been involved in radio astronomy from its inception, with Bell engineer Karl Jansky publishing the first report on "Radio Waves from Outside the Solar System" in 1933. By the mid-1950s, radio astronomy was an established field in the US, UK and elsewhere and awareness of it was growing. It is interesting, however to see reference to this still little-known science appearing in popular culture, long before the use of radio telescopes to track the products of the US-USSR space race brought them to wider public attention.

Kurt Vonnegut's short story "The Euphio Question" (1951) also includes an equally early reference to radio astronomy. The main theme of the story - that signals from outer space can induce a narcotic-like euphoria in humans - is long since disproved. However the story includes an interesting interview between a radio astronomer and a media reporter, reported by a fellow scientist:

The way I understand it, instead of looking at the stars through a telescope, he aims this thing out in space and picks up radio signals coming from different heavenly bodies. Of course, there aren't people running radio stations out there. It's just that many of the heavenly bodies pour out a lot of energy and some of it can be picked up in the radio-frequency band. One good thing Fred's rig does is to spot stars hidden from telescopes by big clouds of cosmic dust. Radio signals from them get through the clouds to Fred's antenna.

That isn't all the outfit can do, and, in his interview with Fred, Lew Harrison saved the most exciting part until the end of the program.

"That's very interesting, Dr. Bockman," Lew said. "Tell me, has your radio telescope turned up anything else about the universe that hasn't been revealed by ordinary light telescopes?"

This was the snapper.

"Yes, it has," Fred said. "We've found about fifty spots in space, not hidden by cosmic dust, that give off powerful radio signals. Yet no heavenly bodies at all seem to be there." (Vonnegut, The Euphio Question, 1951)

This passage makes two important and scientifically accurate observations - first that a major advantage of radio astronomy is its ability to penetrate interstellar and circumstellar dust, and second that there are sources of radio emission that remain unseen in the optical. We now know that the majority of these are quasars (giant black holes consuming a cloud of gas at the centre of galaxies) but in the early 1950s, the origin and nature of this emission was deeply mysterious.

Moving forward in time a little, we see that by the 1960s, a radio telescope was considered to be a natural part of any observatory. An example here can be found in the comic strip associated with children's science fiction television series Fireball XL5. When an astronomical observatory lies in the path of an alien invasion in a 1966 strip by Mike Noble, Professor Mat Matic wonders, without any need for further explanation, whether the astronomers have detected anything with their radio telescopes (see image). Unfortunately, the astronomers in question are doomed to a rapid tentacular demise, so we never get to learn what they were researching. However this demonstrates that by the mid-60s, children in the UK (exposed to Jodrell Bank) were expected to be familiar with the concept.

Moving forward in time a little, we see that by the 1960s, a radio telescope was considered to be a natural part of any observatory. An example here can be found in the comic strip associated with children's science fiction television series Fireball XL5. When an astronomical observatory lies in the path of an alien invasion in a 1966 strip by Mike Noble, Professor Mat Matic wonders, without any need for further explanation, whether the astronomers have detected anything with their radio telescopes (see image). Unfortunately, the astronomers in question are doomed to a rapid tentacular demise, so we never get to learn what they were researching. However this demonstrates that by the mid-60s, children in the UK (exposed to Jodrell Bank) were expected to be familiar with the concept.

Published in 1980, Robert L Forward's novel Dragon's Egg is largely set on the surface of a pulsar - a rapidly spinning, young neutron star - and explores the life that evolves there, and how it is affected by human observation. However the opening sequence follows the initial discovery of the the pulsar, as an interference source affecting radio observations of the Sun by a distant probe. The story here of PhD student researcher Jacqueline Carnot echoes the original discovery of pulsars by Jocelyn Bell Burnell - up to and including an explanation and justification of the recognition received by her supervisor. The radio theme is rapidly superseded as the plot advances, but this episode nonetheless provides an interesting glimpse into academic research astronomy. By contrast James Gunn’s SETI project in The Listeners struggles with underfunding through the opening sections of the book, and eventually makes a breakthrough not through its own equipment, but by analysing data obtained during scientific studies with a vast, 5 mile wide radio astronomy synthesis array in Earth orbit known as the “Big Ear”. While the setting here is 2025, this remains well beyond any equipment we can yet deploy.

A radio observatory appears in Cixin Liu’s novel The Three-Body Problem (novel 2008, translated 2014), although again the focus is not on the science. In this story the observatory is studying the cosmic microwave background radiation - the diffuse field of photons that represent the relic of the Big Bang. Redshifted to a few millimetres in wavelength, these photons must be studied with radio equipment, although using current technologies these have to be above the atmosphere (unlike Liu’s). In any case, in the story astronomical observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation are manipulated so that the strength of the signal spells out a coded message. It is a little unclear whether the alien technology responsible for this phenomenon is actually manipulating the microwave background on large scales or simply the perceptions of its audience.

Veering further into fantasy, author Alan Garner wrote a late sequel to his Weirdstone of Brisingamen series. Set in and around the Cheshire hills, Boneland (novel, 2012) follows one of his earlier characters, Colin, now adult and working as an astronomer at Jodrell Bank Observatory (the environs and Discovery Centre attached to which are described in moderate detail). The theme of the book is memory, folklore and deep time, rather than astronomy, but the book contrasts its fantastic elements against the scientific certainties in which Colin seeks security. Unfortunately, the details of how a world-class radio observatory operates are largely ignored. Available observing time on these facilities is heavily oversubscribed, and awarded through an internationally competitive proposal and assessment process to maximise the scientific return. The idea that local scientists simply walk in and decide on a whim what to observe on any given day (in the case of Colin, the open star cluster M45 - better known as the Pleiades) is outdated at best.

Veering further into fantasy, author Alan Garner wrote a late sequel to his Weirdstone of Brisingamen series. Set in and around the Cheshire hills, Boneland (novel, 2012) follows one of his earlier characters, Colin, now adult and working as an astronomer at Jodrell Bank Observatory (the environs and Discovery Centre attached to which are described in moderate detail). The theme of the book is memory, folklore and deep time, rather than astronomy, but the book contrasts its fantastic elements against the scientific certainties in which Colin seeks security. Unfortunately, the details of how a world-class radio observatory operates are largely ignored. Available observing time on these facilities is heavily oversubscribed, and awarded through an internationally competitive proposal and assessment process to maximise the scientific return. The idea that local scientists simply walk in and decide on a whim what to observe on any given day (in the case of Colin, the open star cluster M45 - better known as the Pleiades) is outdated at best.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his interest in radio astronomy, Fred Hoyle touched on another of the more technical aspects of the field in his novel Comet Halley. When his character contacts the animate comets in the story, they responded on the same frequencies used to reach out to them - predictably but problematically, as the scientist sending the signal used a radio band protected from commercial development because of its significance to astronomy. As Hoyle explains, the protected radio bands have been agreed by international treaty and mark regions of the spectrum where emission from distinctive physical processes in distant objects can be studied. These bands are defined by atomic physics and so cannot be moved. Their use for deliberate broadcasts is banned. In Hoyle's story, a comet saturates receivers working at that frequency and leads to an outcry from the radio astronomy community. Losing one of the protected bands implies that it will no longer be possible to study a phenomenon which is key to interpreting stars, galaxies or quasars from the Earth. Called before the Royal Society, representing the international scientific community, the central character in this story justifies his actions in the common societal interest, and points out that he opted to use the slightly less important 408 MHz band used for mapping the Galactic magnetic field and supernova shocks (as opposed to the pivotal 1.4 GHz waveband of hydrogen, for example). However the long term impact on radio astronomy is recognised and acknowledged.

Another novel which considers radio astronomy as something more than a pretty setting is the Doctor Who tie-in Nightshade by Mark Gatiss (novel, 1992). Here a (fictional) radio telescope is studying emission from a stellar binary but becomes swamped by alien signals. The nature of the binary, and the ultimate way it will end its life in a collision between the two stars is an important plot point, and is discussed in some detail. Pleasingly, a key character in this novel is a now-retired actor who played "Professor Nightshade" in an early television science fiction drama - a clear homage to the classic Professor Quatermass - and the key astronomer character cites his television series as a source of career inspiration. As I’ve discussed before, the influence of science fiction on career aspirations in astronomy is widespread, and, for the generation whose formative years were the 1950s and 60s, the Quatermass serials were a large part of that influence.

Another novel which considers radio astronomy as something more than a pretty setting is the Doctor Who tie-in Nightshade by Mark Gatiss (novel, 1992). Here a (fictional) radio telescope is studying emission from a stellar binary but becomes swamped by alien signals. The nature of the binary, and the ultimate way it will end its life in a collision between the two stars is an important plot point, and is discussed in some detail. Pleasingly, a key character in this novel is a now-retired actor who played "Professor Nightshade" in an early television science fiction drama - a clear homage to the classic Professor Quatermass - and the key astronomer character cites his television series as a source of career inspiration. As I’ve discussed before, the influence of science fiction on career aspirations in astronomy is widespread, and, for the generation whose formative years were the 1950s and 60s, the Quatermass serials were a large part of that influence.

A more modern take on radio astronomy can be found in the short story “Listening Glass” by Alexis Latner (first published in 1991 and collected in Diamonds in the Sky, 2009, ed. Michael Brotherton). Here a new radio telescope under construction in the Bolton crater on the Moon is damaged accidentally. However the detection of a supernova makes its repair urgent, and a great deal of ingenuity is required if the crew are to detect the millisecond pulsar they hope has been newborn at the heart of the supernova. A pulsar is a rapidly spinning neutron star. The tight-wrapped magnetic fields at its poles act like the beams of a lighthouse, sweeping highly energetic radiation, including radio signals, past the observer. Most neutron stars form when a moderately massive star collapses at the end of its life, releasing a supernova. The collapse spins up the star, which then rapidly spins down again as the beam carries away angular momentum. But this process, while well understood theoretically, has never been directly observed. As a character notes,

“Millisecond pulsars are the most accurate clocks in all creation. If we had one in the vicinity of a supernova in progress, we could observe what happened to the timing as the pulsar got hit by gravity waves, radiation, maybe plasma from the supernova. Also, the amount of mass lost in the supernova — and whether or not it breaks up into more than one body — that would register in the signal from a pulsar in the right location. And Bolton is better equipped to read such a signal than any other facility on the Earth or off it.”

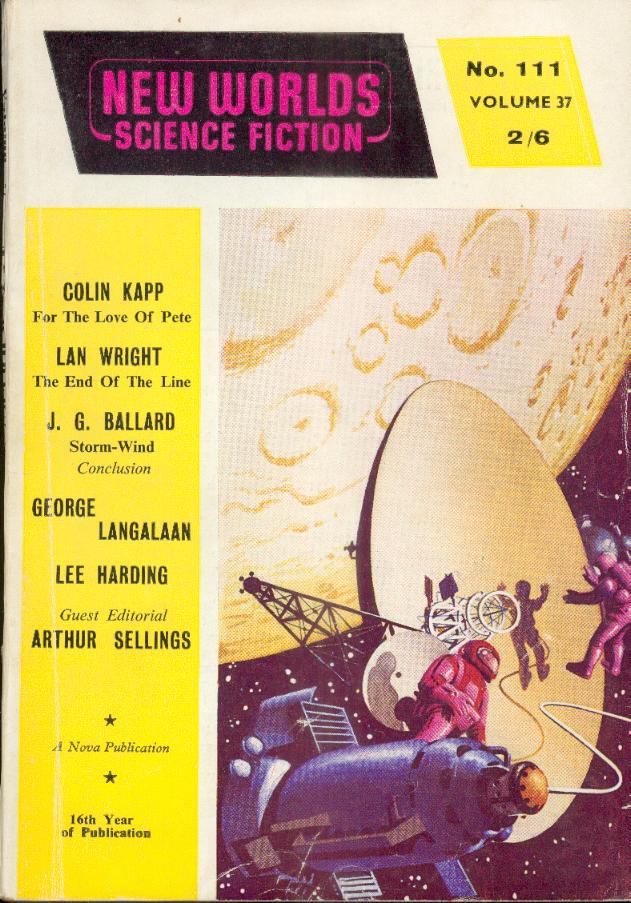

The idea of a lunar radio observatory is long established. In 1961 a dish in  in lunar orbit (credited to Lewis but apparently unrelated to any of the stories in the magazine) was used to capture an image of futurism for the cover of New Worlds magazine. As early as 1965, four years before the first lunar landing, science writer and populariser Willy Ley published an essay in Galaxy Science Fiction magazine on the prospects of building an observatory on the Moon - summarising still older suggestions. He highlighted the then-novel area of radio astronomy as a subfield which would benefit enormously from a lunar farside location. The bulk of rock in the Moon would block radio frequency interference from Earth, including deliberate transmissions, radar, accidental RFI and satellite telemetry or broadcasts. Interestingly, the magazine also included responses from astronomers Donald H Menzel and Robert S Richardson exploring alternatives to and weaknesses in Ley’s arguments, and also discussing lunar observatories in the optical. The idea of a lunar radio observatory remains current in research astronomy, albeit now with more realistic views of the costs and dangers involved.

in lunar orbit (credited to Lewis but apparently unrelated to any of the stories in the magazine) was used to capture an image of futurism for the cover of New Worlds magazine. As early as 1965, four years before the first lunar landing, science writer and populariser Willy Ley published an essay in Galaxy Science Fiction magazine on the prospects of building an observatory on the Moon - summarising still older suggestions. He highlighted the then-novel area of radio astronomy as a subfield which would benefit enormously from a lunar farside location. The bulk of rock in the Moon would block radio frequency interference from Earth, including deliberate transmissions, radar, accidental RFI and satellite telemetry or broadcasts. Interestingly, the magazine also included responses from astronomers Donald H Menzel and Robert S Richardson exploring alternatives to and weaknesses in Ley’s arguments, and also discussing lunar observatories in the optical. The idea of a lunar radio observatory remains current in research astronomy, albeit now with more realistic views of the costs and dangers involved.

Returning to the narrative in “Listening Glass”, Latner’s story is a triumph of ingenuity and a nice analysis of how construction, repairs and material usage would differ on the Moon to those on Earth. It name-checks a large number of familiar Earth-based radio telescopes, as well as describing some interesting astrophysics. It also effectively articulates the determination and commitment required of astronomers to pursue and capture the once-in-a-lifetime transient phenomena that come and go through our skies.

Transient flares from supernovae and gamma ray bursts, the rhythmic clocks of pulsars, the energetic emission from accretion disks around binary stars or quasars, the twisted magnetic fields of solar prominences and the weaker magnetic fields that drive vast currents through interstellar space all create radio signals capable of detection from Earth. Each tells us something different about the way matter reacts with itself and with the magnetic fields that surrounds it. While many of these phenomena have appeared repeatedly in science fiction, there is much more that can be said regarding their physics and the lessons they teach.

Radio astronomy probes some of the most energetic and exciting phenomena in the Universe. Since the advent of this new science in the 1940s, the huge dishes of radio telescopes, pointed at the sky have become emblematic both of the excitement of a scientific future and the mysteries that remain to be discovered beyond our world. The idea that such discoveries might include life as complex and rational as ourselves is too compelling to ignore. Science fiction has captured something of this sense of mystery. Perhaps in future, the science of radio astronomy itself will inspire still more stories exploring its endless possibilities.

"Our Ears on the Sky", Elizabeth Stanway, Cosmic Stories Blog, 16th July 2023.

Notes:

[1] Amongst many other science fiction novels which features Jodrell Bank on its cover for no apparent reason is Angus MacVicar’s Satellite 7 (1958), which is actually set in an experimental military radio tracking station located on a remote Scottish island. In fact, I've started collecting examples of Jodrell Bank references on its own page. [Return to text]

[2] Unfortunately, Comet Halley has little to recommend it besides the cover, with its 400 pages comprising about 100 pages of plot, 50 pages of the author-insert character’s sexual relationship with a young female research assistant, and 250 pages of Hoyle complaining about research funding and politics. Similarly The Fifth Planet (mentioned later) is about evenly divided between Hoyle’s complaints about committees, international politics and social trends, and casual sexual objectification of women, with more space taken up by abstruse theories regarding spacetime and the nature of reality. Relatively little room is left for actual plot or character development. [Return to text]

[3] The cover of the 1974 edition of The Listeners superposes a pictogram based on the Arecibo message on yet another image of the Jodrell Bank 76m Lovell Telescope. Another version contains a rather attractive but somewhat impractical design for a futuristic dish array. [Return to text]

All ideas, opinions and commentary is the author's own and does not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Warwick. All images are sourced online from public domain sources.