IER News & blogs

EU’s Pay Transparency Directive – A lost opportunity for the UK? Blog by Trine P. Larsen

It is nearly fifty years ago that the EU passed its first directive on equal pay for equal work or work of equal value. Since then, equal pay and work-life balance initiatives have formed part of various EU and national policy reforms, laws and collective agreements to promote female employment and reduce the gender pay gap. While mobilising the female workforce has been successful in most European countries, a persistent gender pay gap remains across Europe. To address these structurally embedded gender inequalities, the EU and its Members States have recently adopted the EU’s Pay Transparency Directive (2023). Although the UK is no longer an EU Member State and is not obliged to implement this directive, it remains to be seen whether the newly appointed Labour government will follow suit and adopt similar measures as part of its intention to address the wage inequalities in its election manifesto.

Mobilising the female workforce and narrowing the gender pay gap

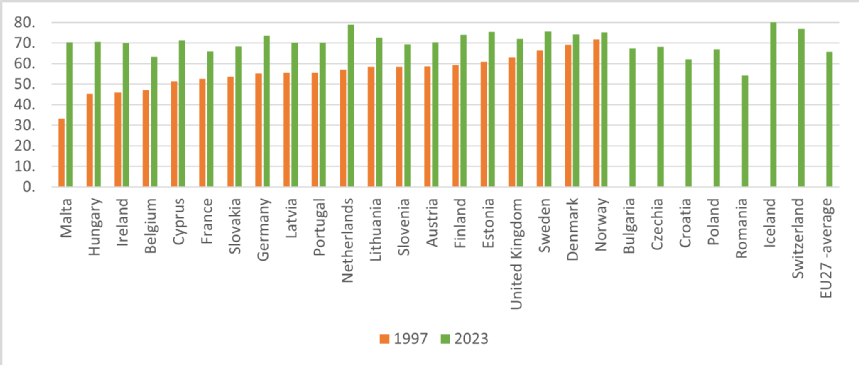

Since the mid-1990s, female employment rates have risen across Europe, especially in Malta, Ireland and some southern European countries such as Italy, Portugal and Spain (Figure 1). In contrast, the Nordic countries had already a comparatively high female employment rate, ranging from 68% in Denmark, to 69% in Sweden and 72% in Norway in 1997. In the UK, most women (63%) were also in paid work in the mid-1990s, and this figure rose to 72% in 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Recent developments in the female employment rate as percentage of all women aged 15-65 for selected years (1997 and 2023)

Source: Eurostat (2024a: 2024b: ONS, 2024a), note that only some European countries have available data for the female employment rate in 1996.

Mobilising the female workforce has not necessarily been matched by progress in closing the gender pay gap. This gap is often measured as the difference between the average gross hourly earnings of men and women, expressed as a percentage of men’s average gross hourly earnings (Eurostat, 2024c). Eurostat figures reveal not only a persistent gender pay gap across most European countries but also marked cross-country variations. For example, the gap ranges from 21% in Estonia to -0.7% in Luxembourg, with countries like Denmark (13.9%) and the UK (14.8%) falling in the middle, but above the EU average of 12.8% in 2022 (Eurostat, 2024: ONS, 2024, Figure 2). Over time, the gender pay gap has narrowed in many countries, with significant reductions observed in countries such as Luxembourg, Ireland, Spain, Belgium, Cyprus, Romania and Italy. In these countries the gap has nearly halved, if not more, between 1997 and 2022 (Figure 2). However, less progress is seen in the Nordic countries, where the gender pay gap remains relatively persistent. In few European countries, such as Portugal, the gap has in fact even widened over the years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Recent development of the unadjusted gender pay gap across Europe for the years 1997 and 2022 (in per cent)

Source: Eurostat (2024c: 2024d; ONS, 2024b), note that only some European countries have available data for the gender pay gap in 1996 and 2023.

The gender pay gap is frequently attributed to the highly segregated nature of the European labour markets. Women tend to be overrepresented in low-wage sectors, and this structural wage disparity is further propelled by their higher likelihood of working part-time, often with few or no guaranteed working hours. In addition, the so-called ‘child penalty’ plays a significant role, as periods of childrearing often lead to long-term negative economic effects on women’s employment opportunities, wages and working hours. This child penalty is frequently cited as a major factor contributing to the persistent gender pay gap across Europe (Kleven et al. 2019).

The European toolbox of gender equality measures

The European toolbox for addressing the gender pay gap is comprehensive. The most recent EU initiatives include the Pay Transparency Directive (2023). This directive directly addresses the gender pay gap by requiring European companies with 100+ employee to publish reports on the gender pay gap and take actions, if their gender pay gap exceeds 5%. The directive also introduces new provisions that penalise companies for non-compliance and offer financial compensation for those who experience pay discrimination. It also prohibits employers from asking about past salaries or current pay of job applicants and compels employers to share information about how pay is set and managed and how promotion and progression criteria are developed (Directive (EU) 2023/970).

The effects of EU’s gender equality measures – recent examples

The EU’s gender equality regulations have pushed many Member States to adopt new legislation and measures to address gender inequalities and wage gaps. For example, the EU has been pivotal for advancing gender equality legislation in Denmark, especially in areas such as equal pay. Similarly, the UK, although no longer an EU Member State, has implemented and retained all of the EU’s pre-Brexit gender equality laws. More recently, the UK government introduced additional initiatives, such as a pay transparency pilot scheme, which was announced in 2022 but later paused in 2024. However, the effects of EU’s new Pay Transparency Directive remains uncertain as the directive is yet to be fully implemented across Europe. Critics argue that the Pay Transparency Directive may fail to tackle the structural embedded pay inequalities due to its focus solely on pay transparency within individual workplaces, rather than across and between sectors. The directive also excludes small and micro-companies—the majority of European businesses—which could jeopardise its effectiveness in reducing wage inequalities. Opponents, especially employers and some liberal- and right-wing political parties, also express concerns about the additional administrative burdens the directive may impose on business, potentially hindering economic growth. In contrast, European trade unions and several socialist and left-wing political parties have been less critical and often welcomed the directive, appreciating its aims to combat the persistent gender pay gap.

What happens next?

It remains to be seen what will happen across Europe and whether the UK will follow suit and adopt measures that match those standards outlined in EU’s Pay Transparency Directive. There is no doubt that equal pay, along with tackling in-work poverty and precarious employment, remains a high priority on the political agenda both in the UK and across Europe. However, despite the well-intended efforts of the EU, national governments and social partners, recent figures suggest that combatting unequal pay remains a significant challenge.