IER News & blogs

The role of lifelong career guidance in a new and changing labour market - blog by Sally-Anne Barnes, Jenny Bimrose and Alan Brown

Since the start of the pandemic, the UK Government has described the numbers of individuals applying for Universal Credit as ‘unprecedented’ with 2.5 million applications since the lockdown in March. So with unemployment levels at an all-time high and global changes to work and labour markets as a result of the pandemic unavoidable, this is the time to think about enhancing the system of support and guidance in the UK. A system is needed that not only supports those out of work to return to the labour market, but also supports those who have had to change their role, and/or take on new roles. What seems likely is that most of those who are more able, more skilled and more adaptable will return to the labour market faster, whilst those who are less skilled and less resilient are more likely to struggle to return to the labour market.

Since the start of the pandemic, the UK Government has described the numbers of individuals applying for Universal Credit as ‘unprecedented’ with 2.5 million applications since the lockdown in March. So with unemployment levels at an all-time high and global changes to work and labour markets as a result of the pandemic unavoidable, this is the time to think about enhancing the system of support and guidance in the UK. A system is needed that not only supports those out of work to return to the labour market, but also supports those who have had to change their role, and/or take on new roles. What seems likely is that most of those who are more able, more skilled and more adaptable will return to the labour market faster, whilst those who are less skilled and less resilient are more likely to struggle to return to the labour market.

A high quality, well resourced lifelong career guidance system can have an important role not only in supporting people back into work, but also helping people adapt to new ways of working and new types of labour markets by learning to adapt and innovate. Those in these new and emerging labour markets will need help to recognise their skills, and support to develop and continue their learning.

Undertaken by IER and colleagues from the University of Jyväskylä, a recent study of lifelong guidance in the UK and Europe examined guidance policy and practice identifying actors and stakeholders involved. The study provides insights into how practice and policy could evolve to address the current and imminent challenges for those transitioning from education to work, those out of work and those trying to adapt to new and changing employment opportunities. The recommendations coming out of the study are particularly timely given the catastrophic impact of the pandemic on labour markets around the world.

What does a lifelong career guidance system look like?

Eleven crucial features of robust lifelong guidance systems were identified by the study. These features provide a framework to think about what an effective lifelong guidance system might look like and, significantly, how services could be developed to support individuals with their education and employment transitions across their lifetime. The features comprise:

- Lifelong guidance legislation provides the foundation for the development of a lifelong guidance system. It can be a tool to clarify responsibilities, entitlements to guidance support, and service delivery mechanism, but there is a need for it to be explicit.

- Strategic leadership refers to how national, regional and local policy and lifelong guidance systems are managed. Where there is a shared vision and strategy, career guidance is integrated into national skills strategies, activities are coordinated, and mechanisms are in place that guide the development, management and delivery of guidance services.

- The scope of provision in different guidance contexts varies according to where guidance provision is situated and how it is organised within and across different guidance contexts. Cross-sectoral provision that, for example, links lifelong learning with work is seen as key to seamless delivery of guidance.

Lifelong guidance and lifelong learning strategies and policies highlight the role of lifelong guidance in education, learning and employment. Where these strategies and polices are coherent within an overarching framework the role lifelong guidance plays in lifelong learning is clear and there is a recognition that people need to reskill and upskill throughout their careers.

Lifelong guidance and lifelong learning strategies and policies highlight the role of lifelong guidance in education, learning and employment. Where these strategies and polices are coherent within an overarching framework the role lifelong guidance plays in lifelong learning is clear and there is a recognition that people need to reskill and upskill throughout their careers.- Coordination and cooperation focuses on the mechanisms that support communication, service delivery and knowledge sharing between the various actors involved in the organisation and delivery of lifelong guidance. Open systems are seen to have strong links and are considered more sustainable.

- The delivery of guidance is represented by a range models that define how services are provided. A holistic model is considered ideal as it is based on a system of individualised and differentiated support relevant to the individual and delivered through a range of specialist partners.

- Labour market information and data are collected and disseminated within lifelong guidance systems to support education planning and policy, as well as to inform guidance services. However, this requires investment and development to ensure high quality information is mediated and supported by professionals.

- ICT strategy reflects how technology is being developed and integrated into lifelong guidance systems. The systemisation of ICT use, such as ensuring there is policy support and workforce development, creates successful integration into support systems.

- ICT operationalisation refers to how technology is used in a lifelong guidance system and for what purposes. ICT is a common element in guidance provision with the potential to be transformative creating a space for user-driven services.

- Professionalisation highlights the qualifications, knowledge, skills and ethical standards required by those delivering lifelong guidance services. This is essential in maintaining a quality system, but also retaining cutting edge practice. This is achieved when there is some form of legislative requirement for qualifications and training.

- Evidence of impact of lifelong guidance refers to the methods by which services and the outcomes are measured and evidenced. Where the process is systematic, it has the potential to inform the development of lifelong guidance systems through feedback loops.

Lessons learnt from across Europe

Across Europe, some countries have developed lifelong guidance systems where individuals receive career guidance support throughout their life-course regardless of whether they are in education or work, or unemployed. This, of course, helps them stay in the work and develop for a changing labour market. Other countries have aspirations for a more developed system, undertaking development in the field.

Across Europe, some countries have developed lifelong guidance systems where individuals receive career guidance support throughout their life-course regardless of whether they are in education or work, or unemployed. This, of course, helps them stay in the work and develop for a changing labour market. Other countries have aspirations for a more developed system, undertaking development in the field.

Interestingly, many countries are facing the same challenges in terms of funding, getting to grips with technology, and working within structures that constrain practice as well trying to align practices with others. However, even in this context new and innovative guidance practice and tools are emerging with aim of providing a seamless service delivery across an individual’s life-course.

Guidance and learning is taking place in more diverse settings with ICT becoming more embedded. It needs to be recognised that a single practitioner, professional group or organisation will no longer be able to respond to the increasing need for support across all diverse user groups. This implies a need to create multi-professional and cross-sectoral networks, which will be more essential in the post Covid-19 labour market.

The study Lifelong guidance policy and practice in the EU: Trends, challenges and opportunities was undertaken by Sally-Anne Barnes, Jenny Bimrose and Alan Brown from IER, together with Jaana Kettunen and Raimo Vuorinen from the University of Jyväskylä.

What is the future of youth skill-building in developing countries in the post Covid-19 era? Blog by Dr Sudipa Sarkar and Bhaskar Chakravorty

Unemployment and scarcity of jobs have long been important concerns for policymakers in developing countries (World Bank, 2012). These issues are crucial for India as the country is home to the world’s largest population of young people ready to participate in the labour force (UNFPA report, 2019). The current situation caused by the Covid-19 outbreak and the subsequent countrywide lockdown is certain to affect employment levels in the country, especially as India has a large informal economy, which is currently bearing the major brunt of the lockdown. In this context, targeted Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs), which have been historically used to cushion the economic shock of such global crises in developing countries, can play an important role (Cazes, Heuer, & Verick, 2011; Imbert and Papp, 2015; World Bank, 2012).

Unemployment and scarcity of jobs have long been important concerns for policymakers in developing countries (World Bank, 2012). These issues are crucial for India as the country is home to the world’s largest population of young people ready to participate in the labour force (UNFPA report, 2019). The current situation caused by the Covid-19 outbreak and the subsequent countrywide lockdown is certain to affect employment levels in the country, especially as India has a large informal economy, which is currently bearing the major brunt of the lockdown. In this context, targeted Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs), which have been historically used to cushion the economic shock of such global crises in developing countries, can play an important role (Cazes, Heuer, & Verick, 2011; Imbert and Papp, 2015; World Bank, 2012).

In India, governments have long engaged in a variety of ALMPs that directly intervene in the labour market (from both demand and supply sides) with the aim of reducing unemployment. Demand side interventions include the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) and supply side interventions comprise several skill-training programmes that aim to increase the skills of the workforce and match them to appropriate jobs. Several skill-building programmes run by the government of India particularly target unemployed rural youth from poor families and aim to provide them with salaried employment after training completion. One such programme, launched in 2014, is the "Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushal Yojana"(DDU-GKY hereafter) which set out to “transform rural poor youth into an economically independent and globally relevant workforce” (DDU-GKY Programme Guidelines, 2016). In this particular programme, skill development is implemented through a Public-Private Partnership mode (PPP model), where registered private sector partners (called programme implementing agencies or PIAs) plan and implement skills training and job placements (DDU-GKY Policy Guidelines, 2016).

Ongoing IER research on a skill-building programme

Before the virus outbreak and lockdown, we, a team of researchers at the IER started studying the effectiveness of this programme in building skills that can help provide employment opportunities to young people in rural Bihar and Jharkhand, two of the poorest states in India. Though our study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), focuses on only one scheme, our findings will have wider applicability as similar programmes are being implemented in other parts of the country.* Examples of such programmes are, the '"Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana" and area-specific programmes such as "Himayat" (in Jammu and Kashmir), and "Roshni" (in 27 left-wing districts across nine states).

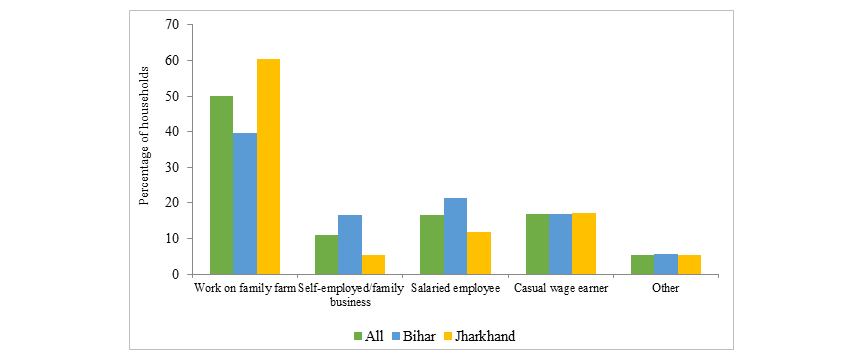

Our baseline sample consists of 1769 young people, mostly from poor households (83% with below poverty line card), unemployed (only 12% did some paid work before taking the training), and with secondary or higher secondary school education (around 85%). About half of the participants report that they ‘work on a family farm’ as the main occupation of the head of their household (Figure 1). The percentage working on a family farm is higher in Jharkhand (60%) compared to Bihar (39%) as many households in Bihar (around 40%) do not own any agricultural land, which explains the historic trend of mass migration to other states for employment, predominantly in the informal sector. Only 16.6% of the participants report ‘salaried employment’ as the main occupation of their household heads, with the figure even lower in Jharkhand (at 12%). According to national statistics, 70 to 80% of non-agricultural employment in Bihar and Jharkhand is in the informal sector (National Sample Survey, 2012). Therefore, casual wage work in the informal sector is probably the only option for the households without any agricultural land. In this context the DDU-GKY training programme (and others like it) may lead to salaried wage employment in the formal sector for this vast workforce, which would otherwise be casual-wage workers or the disguised unemployed in agriculture.

Figure 1: Main occupation of household head as reported by the training participants

Source: IER-XISS baseline survey, 2019-20.

The impact of Covid-19 and lockdown on skill-building programmes

The DDU-GKY scheme in our two study states, Bihar and Jharkhand, mostly consists of residential training, where the participants from rural areas stay on campus or in the accommodation provided by the training centres/PIAs. The training centres are also located in cities or towns where the risk of the virus spreading is much higher. Given the outbreak and subsequent lockdown on 24th March 2020, all training centres closed and participants were sent back to their native villages. Those who finished training and were placed by the PIAs had returned to their native villages or were stuck in different states where they had been working.

One of the major challenges that DDU-GKY will encounter in the post-Covid era is ensuring that participants who were sent home will return to the training centres to continue their training and encouraging others to enrol for training in the near future. In the absence of any data yet collected in post-lockdown, we can only raise questions and conjecture about the post-lockdown period operation of these programmes. These questions include:

One of the major challenges that DDU-GKY will encounter in the post-Covid era is ensuring that participants who were sent home will return to the training centres to continue their training and encouraging others to enrol for training in the near future. In the absence of any data yet collected in post-lockdown, we can only raise questions and conjecture about the post-lockdown period operation of these programmes. These questions include:

1. Is it possible to continue training the unemployed rural youth by providing them with residential training in urban cities? Once the lockdown is lifted and training centres start to operate in cities, young people from rural areas are likely to feel apprehensive about coming to cities and large towns to train. Cities have been most affected by the virus outbreak and returnees from cities have been stigmatised and, in some places, have not been allowed to enter their native villages.

2. Is it possible for the PIAs to provide salaried employment to the poor unemployed youth after training completion? It is also uncertain whether the PIAs will be able to provide job placements to the training participants in the post Covid-19 era. As economies across the world are likely to go through a severe crisis, demand for labour may fall, resulting in high levels of joblessness.

3. If no salaried employment is available, can the skills built through the programme provide opportunities for self-employment in the post Covid-19 period? Finally, those who completed their training just before the virus outbreak and subsequent lockdown may not have been placed into employment by the PIAs or were placed but lost their jobs due to the lockdown. The question is whether these young people can use the skills built through the programme to make an alternative livelihood to sustain them during the economic crisis. For example, those who enrolled in the course on sewing and tailoring (Industrial Sewing Machine Operation or ISMO) may use the skills learned in the training centre to engage in self-employment in their native village and avoid migrating to cities and towns.

3. If no salaried employment is available, can the skills built through the programme provide opportunities for self-employment in the post Covid-19 period? Finally, those who completed their training just before the virus outbreak and subsequent lockdown may not have been placed into employment by the PIAs or were placed but lost their jobs due to the lockdown. The question is whether these young people can use the skills built through the programme to make an alternative livelihood to sustain them during the economic crisis. For example, those who enrolled in the course on sewing and tailoring (Industrial Sewing Machine Operation or ISMO) may use the skills learned in the training centre to engage in self-employment in their native village and avoid migrating to cities and towns.

Conclusion

We have more questions than answers for now. However, we are currently preparing for midline and follow-up surveys of the same sample of participants who took part in the study before the Covid-19 outbreak and lockdown. Therefore, the survey data will provide us with important findings and will reveal issues on which we can only speculate for now.

* Led by Professor Clare Lyonette, the project is undertaken by a team of researchers at the University of Warwick in collaboration with the Xavier Institute of Social Service (XISS), Ranchi, India and is funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Supporting and engaging parents and carers with careers advice to young people in their care - Blog by Sally-Anne Barnes and Jenny Bimrose

A recent report from the Resolution Foundation suggests that youth unemployment could rise by 640,000 this year and the Association of Colleges is predicting around 100,000 leavers will find it difficult to gain work and work-based learning. So with these record unemployment levels amongst young people predicted, an important issue that is likely to emerge strongly for the careers profession from the COVID-19 pandemic is exactly how educational institutions can maximise the impact of their work with parents and carers to support the young people in their care with their career education and progression. This, of course, also has the potential to help young people continue to learn and develop whilst away from their schools for any reason, including any future periods of social isolation that might be necessary as a result of recurrent waves of infection.

A recent report from the Resolution Foundation suggests that youth unemployment could rise by 640,000 this year and the Association of Colleges is predicting around 100,000 leavers will find it difficult to gain work and work-based learning. So with these record unemployment levels amongst young people predicted, an important issue that is likely to emerge strongly for the careers profession from the COVID-19 pandemic is exactly how educational institutions can maximise the impact of their work with parents and carers to support the young people in their care with their career education and progression. This, of course, also has the potential to help young people continue to learn and develop whilst away from their schools for any reason, including any future periods of social isolation that might be necessary as a result of recurrent waves of infection.

A stronger relationship was already being built as schools changed and adapted the ways in which they communicated, supported and worked with parents and carers. However, the news stories in abundance that have recounted how young people in their final year of education will be negatively impacted by a lack of apprenticeships and employment opportunities make it even more important than ever to ensure that young people receive the best possible careers support whilst still in school.

Given that parents and carers will have an ever increasingly crucial role to play in careers education, it is important to understand exactly what works in terms of their support and engagement. A recent survey of parents and young people reported that just three in five parents felt confident in advising their child about ‘how they can achieve their career/job goals’ or ‘what career/job options would be best for them’. So, there remains an unanswered question as to what works in engaging and involving parents and carers to support their understanding of careers options and, importantly, their confidence in providing careers advice.

Impact of parental and carer involvement in careers

An international review, undertaken by IER, has just been completed. It examined evidence on what works in engaging and involving parents and carers in careers activities so that they feel more confident in the careers advice they give.

The review revealed how parents and carers undoubtedly have the potential to influence the career development of young people, both positively and negatively. Examples of practice identified in the review tells us that shared parental-child careers education and guidance experiences have positive outcomes for young people. These shared conversations and experiences support career development and confidence in career decisions. Involving and engaging parents in careers can positively help young people with their future planning, confidence, goal setting and career decision-making.

The review revealed how parents and carers undoubtedly have the potential to influence the career development of young people, both positively and negatively. Examples of practice identified in the review tells us that shared parental-child careers education and guidance experiences have positive outcomes for young people. These shared conversations and experiences support career development and confidence in career decisions. Involving and engaging parents in careers can positively help young people with their future planning, confidence, goal setting and career decision-making.

Whilst involving parents in careers, education and guidance is neither new nor innovative, we found that parental involvement often remains somewhat marginal, both in the UK and internationally. Parental involvement is often more aspirational than systematised or mandated. Interestingly, the review reveals how parental engagement in careers education and guidance in the UK is moving away from passive forms of involvement and information giving, to creating spaces for active engagement, collaboration and communication between parents and educational institutions.

What could schools and colleges do to engage parents?

Despite the broad recognition of the importance of parental involvement, there is a lack of evidence on what, exactly, are the best ways for schools and colleges to engage parents. Drawing upon the experiences from practice in the UK and internationally, it is possible to draw out ideas on what could be done to engage parents and carers. These are detailed in the practice report and include suggestions to:

Despite the broad recognition of the importance of parental involvement, there is a lack of evidence on what, exactly, are the best ways for schools and colleges to engage parents. Drawing upon the experiences from practice in the UK and internationally, it is possible to draw out ideas on what could be done to engage parents and carers. These are detailed in the practice report and include suggestions to:

- Create parent-friendly environments with activities to draw parents into the school or college, such as breakfast and coffee clubs, and career guidance sessions for parents.

- Promote and communicate careers activities across the curriculum, such as asking parents to contribute to classroom activities, getting them involved in homework activities and through careers days. This will help ensure careers is part of an ongoing conversation.

- Build on current parental engagement in the school or college and so look at where parents and carers are involved and introduce careers conservations and activities.

- Involve parents and carers in the development of the careers strategy and careers education and guidance activities to encourage support and interest.

- Redesign existing activities to involve parents and that they are tailored to reflecting different expectations, needs and aspirations, as well as recognising that there will be different levels of engagement at different times.

- Design new activities that engage parents, employers and the local community, such as ‘meet the employer events’, ‘guess my job’ and informational events on topics requested by parents that involve local experts. Try to ensure that the parent-school and parent-college relationships are not reduced to a static series of concrete activities.

- Develop ‘peer communities’ of careers practitioners and teachers within and across schools and colleges to support their skill and knowledge development in engaging parents and carers, ensuring new and interesting practices are disseminated, with their uptake encouraged and supported.

What next?

There is clearly a need for parents and carers to be effectively supported by schools to develop their knowledge and understanding of choices and future careers so that they, in turn, can provide better careers support and advice for their children. The review has highlighted a need for further evidence to be collected on what works best, to inform a national strategy for engaging parents, with emphasis on allowing individual schools and colleges to tailor their approaches to reflect the needs of their communities. Moving forward, trying out new activities that engage parents and carers, plus learning from each other and building on what works will be essential.

Profiling of job seekers to help target support - Blog by Dr Sally Wright

While we may be in unprecedented times, a picture is already starting to emerge about the colossal impact that Covid-19 is having on labour markets, jobs and people.

While we may be in unprecedented times, a picture is already starting to emerge about the colossal impact that Covid-19 is having on labour markets, jobs and people.

The measures being implemented by countries to address the spread of Covid-19 are necessary as they will save lives but they are having a devastating impact on workers around the world. For example, in mid-March 2020, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimated that lockdown measures had already affected around 2.7 billion workers, representing around 81% of the world’s workforce. Moreover, the pandemic has intensified and expanded since the ILO’s initial estimates were published.

Record levels of unemployment predicted

While the full societal impact of the pandemic may never really be known, given the enormity of what is unfolding, record high levels of unemployment are foreseen in most countries. While there is always a time lag with official statistics, it was shocking to read that private sector firms in the US cut 20 million jobs in the month of April, making it the worst ever for layoffs and leading to historic unemployment.

While in the UK, where the government put in place a job protection scheme, some 6.3 million workers were temporarily furloughed in the two week period to 23 April. This equates to nearly one quarter of the UK workforce. In addition, around 1.8 million people lodged benefit claims in the last two weeks of April alone, seeing the volume of claims increase ten-fold in one particular week in April.

Covid-19 might not discriminate but labour markets do

We know that while the effects of the pandemic are wide-ranging, in developed economies certain groups of workers are being harder hit than others. For example, workers in essential services are facing increased risks to their health whereas sectors such as retail and wholesale trade, accommodation and food services and manufacturing are among those worst affected in terms of closures.

Before the onset of the pandemic, many of the jobs in these hard hit sectors were precarious, low-paid and poor quality jobs. Also, young people, lower skilled, migrants and women tend to be over-represented in these types of jobs. We also know that recessions can exacerbate previous inequalities.

It is difficult at this stage to predict how long it might take for the various economies to recover. So, it follows that it is difficult to predict how many workers will keep their jobs versus how many will become unemployed.

The final scale of job loss in each country will depend, in part, on the effectiveness of the support measures that governments put in place to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

The costs of unemployment are high

Being unemployed, particularly if the spell of unemployment is lengthy, can result in scarring. It can negatively impact on both a person’s mental and physical wellbeing, as well as cause long-term damage to the person’s future income and career development.

Beyond their initial responses, governments will need to shift their efforts toward strategies aimed at dealing with the longer-term impacts of this crisis.

Supply-side support such as subsidies, grants and tax holidays to existing and new start-up businesses will likely be important to help sustain and create jobs. Governments will also need to provide demand-side support such careers guidance, training and active labour market programmes (ALMPs), where governments intervene in the labour market to help unemployed people back into work.

Supply-side support such as subsidies, grants and tax holidays to existing and new start-up businesses will likely be important to help sustain and create jobs. Governments will also need to provide demand-side support such careers guidance, training and active labour market programmes (ALMPs), where governments intervene in the labour market to help unemployed people back into work.

Profiling to target scarce public funds

Providing individual and tailored job search assistance and advice to unemployed people can be costly to deliver. However, unemployment itself has costs for individuals, the economy and society. Fortunately, some people will not remain out of work for very long.

For others, finding a new job will prove difficult. Sadly, some people will remain out of work for long periods, some will be forced into early retirement, and many young people may find it virtually impossible to get a foothold in the paid workforce when they finish their studies.

While current policy thinking is to encourage the development of career management skills and greater self-reliance among job seekers, targeting more intensive guidance support on those unemployed people who are least able to help themselves is one way to prioritise the allocation of already scarce public funds. This is where profiling, or segmentation, of job seekers can be useful.

While current policy thinking is to encourage the development of career management skills and greater self-reliance among job seekers, targeting more intensive guidance support on those unemployed people who are least able to help themselves is one way to prioritise the allocation of already scarce public funds. This is where profiling, or segmentation, of job seekers can be useful.

Profiling is a recognised procedure for identifying and allocating job seekers to different categories, which can indicate which support measures they are entitled to access. It can also be used to help identify those job seekers that are most likely to benefit from early intervention, such as career guidance, soft skills development, help with job search activity, retraining, and so on.

In 2015, we, along with colleagues at ICF International, undertook research for the European Commission on profiling methods in European Public Employment Services (PES).

We mapped the profiling tools in place across EU Member States and other countries to identify how they are used; what are enablers and barriers to implementing tools; what works and does not work with different profiling tools; and implications for introducing tools for PES staff, services, job seekers and caseworkers.

We found that most PES in Europe are using profiling as part of an integrated approach to support job seekers, which may also include training, career guidance and counselling and ALMPs.

Our research included in-depth case studies on the evolution of profiling in eight countries: UK, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Slovakia, Canada and Australia. Evidence from the case studies suggests that while statistical profiling is still viewed as a good tool to support efficient resource allocation, there has been a shift away from it towards profiling to approaches where caseworkers have more discretion. Recent research by the OECD also highlights the role of the caseworker and that they can support the implementation and outcomes of profiling.

Regardless of which profiling methodologies are used, caseworkers were found to play a vital role. Their support in using, implementing, interpreting and understating the profiling methodology are key to its success.

In addition, for profiling to be effective, good labour market and vacancy information needs to be built into the system and regularly updated.

As record numbers of people register as unemployed, many of whom will have multiple and complex needs, PES merit being well resourced. For more about trends and developments in methods to profile job seekers, follow the link to our report.

What are the implications of COVID-19 for Coventry and Warwickshire? Dr David Owen

The UK, like most other countries, introduced a “lockdown” in late March in order to reduce contact between people thereby reducing infections and “taking pressure off” the National Health Service. This involved preventing most businesses involving social contact to stop operating and for workers to work from home wherever possible. The implication was a huge cut in economic activity. The National Institute for Economic and Social Research made estimates of considerable economic recession. The Bank of England’s view (on May 7th) of the probable impact of the lockdown is that the UK economy will shrink by 14% in 2020 but rebound quickly, with growth of 15% in 2021.

The UK, like most other countries, introduced a “lockdown” in late March in order to reduce contact between people thereby reducing infections and “taking pressure off” the National Health Service. This involved preventing most businesses involving social contact to stop operating and for workers to work from home wherever possible. The implication was a huge cut in economic activity. The National Institute for Economic and Social Research made estimates of considerable economic recession. The Bank of England’s view (on May 7th) of the probable impact of the lockdown is that the UK economy will shrink by 14% in 2020 but rebound quickly, with growth of 15% in 2021.

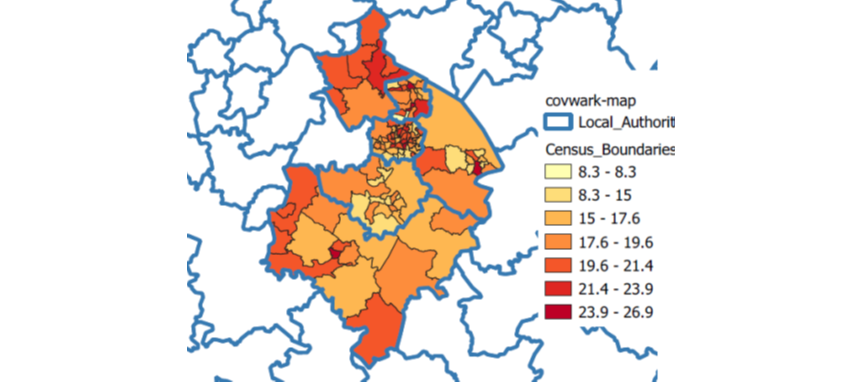

This blog presents tentative estimates of the possible impact of the lockdown on employment and enterprises within the Coventry and Warwickshire local enterprise partnership (LEP) area and for small areas within Coventry and Warwickshire.

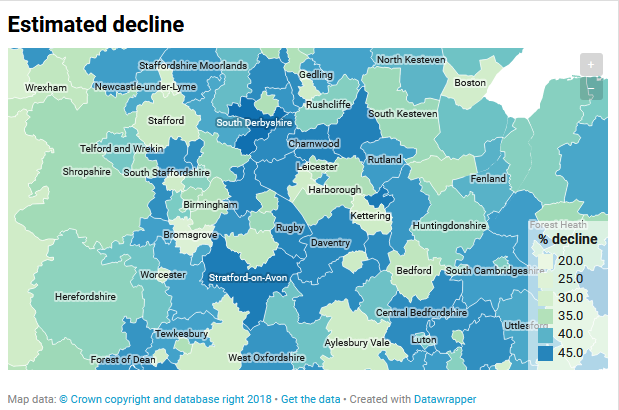

The Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP) estimated the impact of the lockdown at the local authority scale, drawing upon estimates from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). They estimate the decline in economic output to be nearly 50% in parts of the Midlands and the North West in the second quarter of this year. Their estimates of percentage decline in output (GVA) for the neighbouring area are presented in the Figure 1. Loss of output is largest in Stratford-on-Avon (46.2%), North Warwickshire and Rugby (both 45%), and lower in Coventry (36.7%), Nuneaton (35.6%) and Warwick (34.1%).

Figure 1: CPP estimates of GVA decline by local authority district

Source: Centre for Progressive Policy

Using the results from Wave 3 of the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Business Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for the period 6 April to 19 April 2020 crude estimates of the possible impact of the lockdown for the LEP area as a whole and for areas within it are provided . This survey revealed that 23% of the businesses which responded had temporarily closed or paused trading, while 23.4% had experienced a loss of turnover of over 50% with a further 20.4% experiencing a loss of turnover of between 20% and 50%. These percentages are reported for the SIC 2007 industry sections in which the response rate was high enough to report.

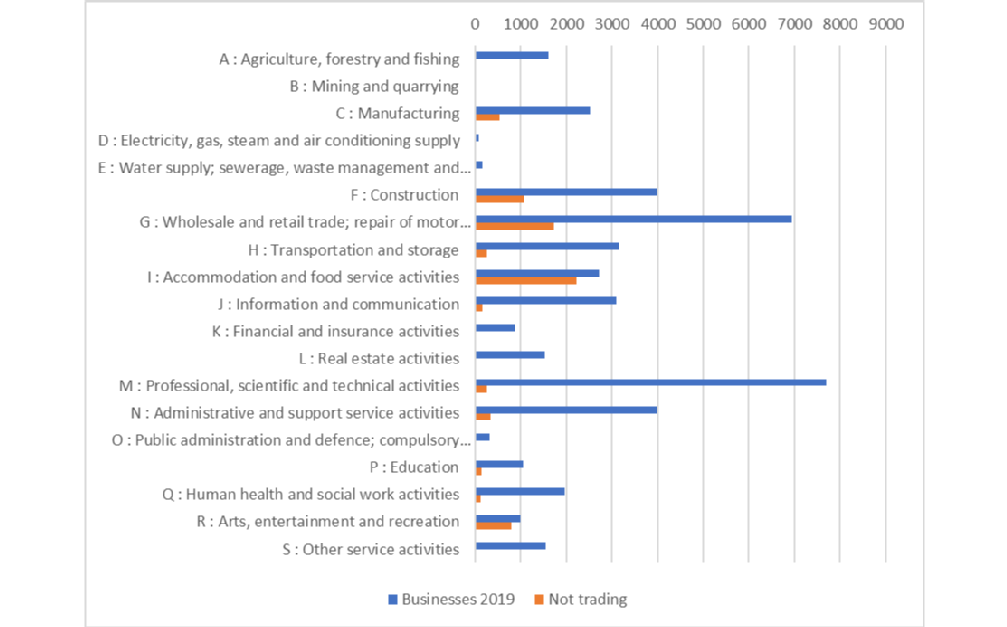

Here, these estimates are applied to UK Business Counts for the LEP area and the constituent local authority districts and Middle Layer Super Output Areas within it to present tentative estimates of the impact of the lockdown and its geographical variation. Figure 2 presents the distribution of businesses (local units) by industry section in 2019 and the estimated number not trading within the LEP. The estimated numbers not trading are highest for accommodation and food service activities and wholesale and retail trade. The impact of closures is greatest upon arts, entertainment and recreation.

Figure 2: Industrial breakdown of businesses in 2019 and estimated number of businesses not trading

Source: UK Business Counts and IER estimates

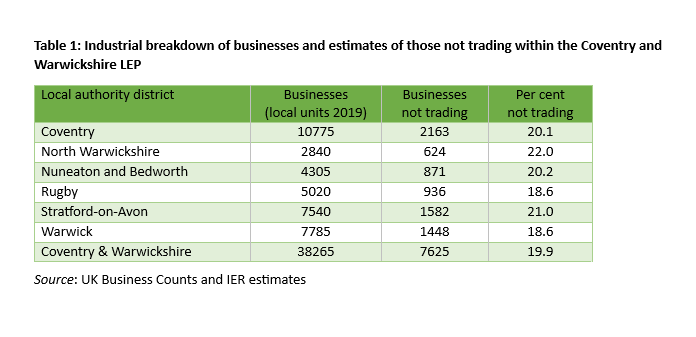

Applying the proportion of businesses not trading to the count of businesses in each section yields the results presented in Table 1 for the Coventry and Warwickshire LEP and the six local authorities within it: The estimated percentage of businesses not trading is highest in North Warwickshire and lowest in Rugby and Warwick.

Figure 3 presents the geographical distribution of businesses not trading as a percentage of businesses present in 2019 (for those industries for which ONS reports this percentage). There are marked spatial variations, with higher percentages in the centre and north-east of Coventry, central Rugby, the centre of Stratford-upon-Avon, and Nuneaton. There are also high percentages in more peripheral locations, e.g. southern Stratford-on-Avon district. These are probably areas in which manufacturing plants are located. In contrast, the towns of Warwick district display lower percentages of businesses not trading.

Figure 3: Estimated percentage of businesses not trading within the Coventry and Warwickshire LEP area

Source: UK Business Counts and IER estimates

Please bear in mind that the estimates presented here are based on a very simple methodology and do not incorporate any factors specific to the local economy. Like the CPP estimates, they provide indicators of the potential geographical pattern of vulnerability to recession, deriving from the industrial structure of localities.