Co-producing knowledge on cultural healing practices: The Yru of Laos

Thipphaphone (Kee) Xayavong, Global Sustainable Development, University of Warwick

Marco J Haenssgen, Global Sustainable Development, University of Warwick

The education-health-development nexus

Education is a key priority in global development agendas. Lao PDR is a country that follows this mindset. In the effort to emerge from its “least developed country” status,1 the country’s government has framed education as a tool to convert the Lao population into,

“good citizens, disciplined, healthy, knowledgeable, highly-skilled with professionalism in order to sustainably develop the country, to align and be compatible with the region and the world.” (Ministry of Education and Sports, 2015:7)2

Nominal gains have indeed been made: Primary education net enrolment has reached 98.8% in 2016, and 80.9% of children completed primary school in 2015/16 compared to 48% in 2007/08.3 But problems persist despite apparent progress. With a population of about 6.9 million, there are 50 official ethnic groups recognised by the government.4 The majority is ethnic Lao Loum, and their language is the only official language of the country. Other ethnicities have their own distinct cultural backgrounds, may not speak Lao as their mother tongue, and are reported to experience barriers to accessing education and health services.5 Inequalities in access to education therefore remain, and people from rural areas and ethnic minorities are particularly excluded.2,5,6

The issues compound further beneath the surface. Although research has asserted wide-ranging positive impacts of education on livelihoods especially in low- and middle-income countries, several recent studies have documented counter-intuitive and potentially problematic relationships between formal education and people’s everyday practices in the context of health behaviour and medicine use – for instance in Lao PDR,7 Thailand,8 and China.9,10 Do we have to challenge (yet again) the role of “education” in global development, whose importance among intergovernmental organisations such as UNESCO,11 UNICEF,12 and WHO13 appears to be beyond doubt?

|

Map of Lao PDR and Champassak province. (Source: Wikimedia Commons user Hdamm) |

These issues prompted us to study the often taken-for-granted link between education and health behaviour in rural Lao PDR, with special focus on the lives and realities of ethnic groups whose voices and worldviews are often neglected in global policy discourses.14,15 The commonly assumed pathway to better health of higher educated people is that they acquire more skills, have better access to resource, and earn credentials for social and economic benefits.16 However, lessons from the Yru then remind us that “everyday cultural heritage” – a marker of cultural knowledge17 – is a formidable force of both the wellbeing of communities and their complex and often syncretic health-seeking behaviours.

Everyday heritage in health and wellbeing

Our study is located in Paksong District in the West of the Southern Lao province of Champassak (see map), which had a poverty rate of 15.5% in 2015,18 and where the Mon-Khmer language group of the Yru is spoken by approximately half of the rural district population.19 Our research takes place among others in Namtang village (pop. 1114), involving community consultations and interviews with the Yru people, who live there in coexistence with the Lao Loum (Tai Lao) ethnic group.

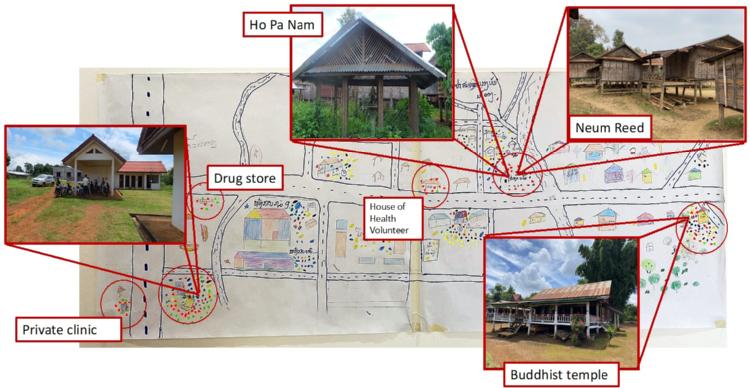

Almost all Lao children have access to primary education.3 The local school in Namtang additionally enables access to secondary education for a majority of villagers and neighbouring communities. And the participants of our community consultations indeed value education as a means to advance and improve human behaviours, livelihood, and development. In the villagers’ perception, education then actively links to health-related belief and practices, which manifests in access to easily available formal healthcare services including a health centre, a private clinic, and a drugstore in Namtang village.

|

Participatory mapping by senior citizens depicting healthcare and healing locations in Namtang village and their corresponding real-life locations. The top two images depict the Neum Reed, a ritual house for Yru ceremonies. The coloured stickers indicate treatment preferences. (Source: research materials. Image credit: Thipphaphone Xayavong.) |

But schooling is not the only influence on health practices and well-being. Other social and cultural factors, such as traditions and family and community relations, continue to shape local health practices. Indeed, the community map above depicts a local Buddhist temple (bottom right corner), which both youths and senior villagers saw as a main destination for healing and for health knowledge:

“I used to be a monk. The ways I took care of my health were based on the Buddha's teaching, meditation, and the Five Precepts of Buddhism.” (Youth Participant)

|

A demonstration of using Lao Hai (a liquor jar) in Peng Reed ritual. In the actual event, a small chicken (sometimes pork for bigger event) and Lao Hai are the two main offerings that people use to give tribute to the spirits of their parents, or spirits in nature (river, forest, lake). The ritual is led by respected elders in the community have inhabited the role from their ancestors. (Image credit: Sai, Research Assistant in Namtang Village.) |

While this is not uncommon, the Yru specifically also maintain an intangible cultural heritage called Reed (“mores” in English). It can be understood as the governing rules of the community, which ban for instance rice milling before 6am or shooting guns in the village and which require rectifying rituals to restore well-being and to prevent misfortune.

The Reed of the Yru culture exemplifies the multiple dimensions of health and well-being, which complicates the often-assumed link between formal education and healthcare service utilisation. In contrast to health and education policy narratives that emphasise individual responsibility, the Reed is a collective matter that determines the community’s health and wellbeing: If any individual breaks the Reed, it could disrupt normalcy and provoke unusual injuries, death, or loss of community members. To live a healthy life, taking care of oneself is therefore not enough; the respect of the social contract established by the Reed needs to be observed as well. Everyday heritage in the form of rituals involving for instance an offering of animal and ceremonial drink reproduces this social contract, making it a collectively produced form of well-being. The Reed is indeed said to be “necessary” for healing as it coexists with and infuses into the mainstream provision of formal healthcare services:

“If we cannot be treated at the hospital, or from the temple, then we correct the Reed.” (Senior villager)

Opening up mainstream narratives with participatory research

Social and spiritual dimensions of well-being are often missing in arguments about health, education, and their linkage. This project therefore chose a range of participatory methods that are more capable of capturing community perspectives and broader social and cultural aspects of their life.20 We started with a series of consultations with different stakeholders, including the health department, health workers, village authorities, health volunteers, and villagers. We then trained a group of research assistants for this project, whom we recruited from the participating villages. Through their perspectives, they were able to comment on the draft research agenda and to make substantial modifications that better suited the local context. The research assistants then took leading roles as co-facilitators in the subsequent community consultations.

|

|

Hear local voices about the Reed of the Yru culture. (Source: interview by Thipphaphone Xayavong, used with media consent and permission) |

The community consultations again used participatory techniques that ranged from role plays via peace circle discussion groups to community mapping. This participatory approach provided a safe space for the community members to share their experiences in education and health. We deliberately encouraged the use of Yru language. The participants often chose to speak Lao because of Thipphaphone’s presence (the lead researcher) but would also comfortably switch back to Yru language when they tried to communicate and understand complex concepts. This bilingual setup actually facilitated the workshop’s flow, mutual learning, and the co-production of knowledge. Other, art-based techniques like participatory mapping and role-playing helped create a relaxing and enjoyable space for people to freely tell their stories. Compared to conventional research methods (which we used as well, in this and previous projects),21 the participants took more control of what kind of information they wanted to present and how they built their narratives.

On reflection, the most important benefit of the participatory approach was that it helped redefine the relationship between the researcher and community members. Although it is difficult to eliminate unbalanced power relations throughout the research process,22 participatory approaches make easier to observe this dynamic closely, reflect on it, and to respond. For instance, after completing the first consultation with youth community members, Thipphaphone met the research assistants and village chief for a reflexive discussion whether adjustments of the agenda and reassignment of the roles in the next workshop were required. It emerged that, contrary to the workshop with youths, our research assistants were not confident to take the leading role in facilitating the subsequent workshop with senior participants. The project was able to adapt immediately to these power relations as the facilitators gave the lead facilitator role back to Thipphaphone. Although power dynamics therefore doubtlessly exist, the reflective and immediate actions from the research team helped to keep power relations in balance and in line with local customs – and accommodated thus our effort to build more equitable participation for everyone in the research process.

Towards heritage-sensitive education and development policy

Research on the role of culture in promoting health is not new.23,24,25 Our study, however, does not merely regard cultural heritage as an instrument to promote health but instead focuses on its genuine and core value in shaping health practices and producing community well-being. Working with the Yru community in Namtang village allows us to reflect on how everyday heritage reproduces the beliefs and behaviours that coexist and coevolve with so-called modern medicine. Maintaining good health and well-being is therefore not a mere matter of individual responsibility to stay physically healthy, but a collective community process of cultural production. Intangible cultural heritage such as Reed defines the relationship of individuals to their family, community, and spaces (e.g. Neum Reed), and it is necessary to observe it in order to maintain individual and community well-being and health on favourable terms.

The voices of ethnic groups help us reflect on and challenge mainstream policy positions: If development policy promotes secular formal education that crowds out traditional customs, are we not prone to undermining cultural practices that indirectly affect physical health but that also directly constitute non-physical dimensions of well-being? Indeed, modernisation paradigms and their quest for “good citizens, disciplined, healthy, knowledgeable, highly-skilled with professionalism” may accidentally threaten multidimensional health despite their good intentions.2 Heritage-sensitive participatory approaches – and, ultimately, heritage-sensitive development policy26 – can help safeguard the perspectives and lives that are often marginalised in mainstream discourses.

Want to learn more about Yru culture and Learning Spaces?

Follow up on this topic with a Webinar given by Thipphaphone on 16 Oct 2021 on "Wellness and Wisdom: Yru Health Practices and Beliefs." This webinar was organised by the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC), a leading cultural centre based in Luang Prabang, Lao PDR.

References

- Oraboune, S. (2013). Lao PDR's development toward LDC graduation by 2020. Paper presented at the Asia-Pacific Regional Workshop on Graduation Strategies from the Least Developed Country Category as part of the Implementation of the Istanbul Programme of Action for the LDCs, 4-6 December 2013, Siem Reap, Cambodia.

- Ministry of Education and Sports. (2015). Education and Sport Sector Development Plan (2016-2020). Vientiane: Ministry of Education.

- Government of Lao PDR. (2018). Voluntary national review on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Vientiane: Government of Lao PDR.

- Open Development Laos. (2019). Ethnic minorities and indigenous people. Available at https://laos.opendevelopmentmekong.net/topics/ethnic-minorities-and-indigenous-people/

- World Health Organization. (2018). Overview of Lao Health System Development 2009-2017. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for Western Pacific.

- Chounlamany, K. (2014). School education reform in Lao PDR: good intentions and tensions? Revue internationale d’éducation de Sèvres, Education in Asia in 2014: what global issues?, 3766.

- Haenssgen, MJ, Charoenboon, N, Zanello, G, Mayxay, M, et al. (2019). Antibiotic knowledge, attitudes, and practices: new insights from cross-sectional rural health behaviour surveys in low- and middle-income Southeast Asia. BMJ Open, 9, e028224. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028224

- Haenssgen, MJ, Charoenboon, N, Althaus, T, Greer, RC, et al. (2018). The social role of C-reactive protein point-of-care testing to guide antibiotic prescription in Northern Thailand. Social Science & Medicine, 202, 1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.018

- Diao, M, Shen, X, Cheng, J, Chai, J, et al. (2018). How patients’ experiences of respiratory tract infections affect healthcare-seeking and antibiotic use: insights from a cross-sectional survey in rural Anhui, China. BMJ Open, 8(e019492). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019492

- Sun, C, Hu, YJ, Wang, X, Lu, J, et al. (2019). Influence of leftover antibiotics on self-medication with antibiotics for children: a cross-sectional study from three Chinese provinces. BMJ Open, 9(12), e033679. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033679

- UNESCO. (2016). UNESCO strategy on education for health and well-being: contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UNICEF. (2015). The investment case for education and equity. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- WHO. (2021). WHO guideline on school health services. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Keller, RC. (2006). Geographies of power, legacies of mistrust: colonial medicine in the global present. Historical Geography, 34, 26-48.

- Pratt, B, Sheehan, M, Barsdorf, N, & Hyder, AA. (2018). Exploring the ethics of global health research priority-setting. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(94). doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0333-y

- Raghupathi, V, & Raghupathi, W. (2020). The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Archives of Public Health, 78(1). doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5

- Auclair, E, & Garcia, E. (2021). Making visible attachments: artists as a lever for highlighting a sense of place and emotional attachments to heritage: articulating public art and urban renewal in Porto-Novo (Benin). In J Lesh & R Madgin (Eds.), People-centred methodologies for heritage conservation: exploring emotional attachments to historic urban places (pp. 212-227). London: Routledge.

- Coulombe, H, Epprecht, M, Pimhidzai, O, & Sisoulath, V. (2016). Where are the poor? Lao PDR 2015 census-based poverty map: province and district level results. Vientiane: Ministry of Planning and Investment.

- Government of Lao PDR. (2021). Lao DECIDE info: informing decisions for sustainable development. Available at http://www.decide.la/en/

- Ansloos, JP. (2018). “To speak in our own ways about the world, without shame”: reflections on indigenous resurgence in anti-oppressive research. In M Capous-Desyllas & K Morgaine (Eds.), Creating social change through creativity: anti-oppressive arts-based research methodologies (pp. 3-18). Cham: Springer.

- Haenssgen, MJ, Xayavong, T, Charoenboon, N, Warapikuptanun, P, et al. (2018). The consequences of AMR education and awareness raising: outputs, outcomes, and behavioural impacts of an antibiotic-related educational activity in Lao PDR. Antibiotics, 7(4), 95. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7040095

- Wallerstein, N, & Duran, B. (2008). The theoretical, historical and practice roots of CBPR. In M Minkler & N Wallerstein (Eds.), Community-based participatory research: from process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 25–46). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Sofaer, J, Davenport, B, Sørensen, MLS, Gallou, E, et al. (2021). Heritage sites, value and wellbeing: learning from the COVID-19 pandemic in England. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(11), 1117-1132. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2021.1955729

- Ander, E, Thomson, L, Noble, G, Lanceley, A, et al. (2013). Heritage, health and well-being: assessing the impact of a heritage focused intervention on health and well-being. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 19(3), 229-242. doi: 10.1080/13527258.2011.651740

- Wexler, L. (2009). The importance of identity, history, and culture in the wellbeing of indigenous youth. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 2(2), 267-276. doi: 10.1353/hcy.0.0055

- Auclair, E, & Fairclough, G (Eds.). (2015). Theory and practice in heritage and sustainability: between past and future. London: Routledge.

About the Authors

Thipphaphone (Kee) Xayavong is a Co-Principal Investigator of the Learning Space project and a EUTOPIA PhD Student in Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick and in the Department of Geography at the CY Cergy Paris Université. His master's degree in Peace Education influences the Learning Space project as it critically investigates the role of education and its effects on the health beliefs and behaviours of the rural populations and ethnic people. He is particularly interested in utilising participatory research approaches to engage community members in co-producing knowledge that challenges the dominant research discourses.

Marco J Haenssgen is Assistant Professor in Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick. Focusing on the Southeast Asian region, he applies social science techniques and mixed-method research to interdisciplinary problems including ecosystem conservation, planetary health, technological change, drug resistant infections, and the evaluation of policies and behavioural interventions.

Related Studies

Haenssgen, M. J., Charoenboon, N., Thavethanutthanawin, P., & Wibunjak, K. (2020). Tales of treatment and new perspectives for global health research on antimicrobial resistance. Medical Humanities, 47(4). doi: 10.1136/medhum-2020-011894

Haenssgen, MJ, Xayavong, T, Charoenboon, N, Warapikuptanun, P, et al. (2018). The consequences of AMR education and awareness raising: outputs, outcomes, and behavioural impacts of an antibiotic-related educational activity in Lao PDR. Antibiotics, 7(4), 95. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7040095

The Learning Space Project

Situated in the province of Champassak in rural southern Laos, the Learning Space project studies the impact of primary and secondary school education on the health of ethnic minority groups. By investigating social, political, and cognitive mechanisms underlying these impacts, the researchers challenge the conventional wisdom that education automatically and intrinsically benefits health beliefs and behaviour. Co-led by Thipphaphone Xayavong and Marco J Haenssgen, the project takes place with co-supervision from Elizabeth Auclair (CY Cergy Paris University) and in collaboration with Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD) Laos, the University of Health Sciences (UHS) and community-based and non-governmental organisations such as Namjai Community Association, Gender Development Association, and the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC) in Luang Prabang. The project is supported by funding from the GRP Connecting Cultures, the Institute of Advanced Study, the Warwick Institutional Research Support Fund, IRD Laos, and a EUTOPIA PhD Co-Tutelle studentship, and operationally also by TAEC and UHS.