IER News & blogs

Bad jobs, the bad jobs trap and the Brexit vote

Despite all of the talk about inter-generational betrayal by the old of the young, the largest ratio to vote leave was amongst low-skilled workers (70%). Their frustration and desire for something to change is understandable. They are in bad jobs, are too often stuck in these jobs and jostle more in these jobs with migrant workers. Their situation is a symptom of three developments that have occurred in the UK labour market since the economic crisis. First, job polarisation has consolidated. Second, non-standard employment has increased in the worst jobs. Third, UK-born workers have benefitted less from employment restructuring.

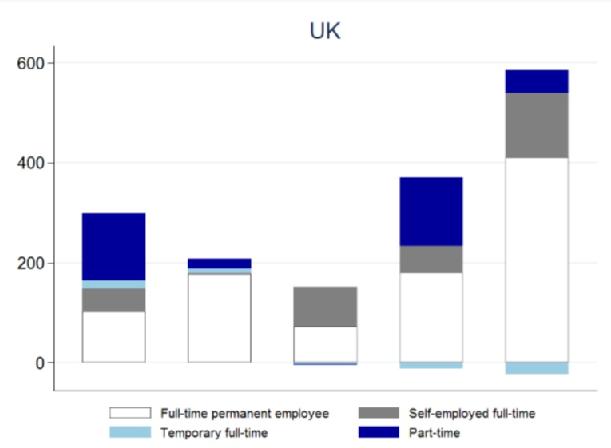

Levels of skill and pay are linked. Using pay as a proxy for job quality then dividing the pay range of jobs into quintiles and charting the expansion and contraction of the number and proportion of jobs in each quintile over time, Eurofound has been assessing employment restructuring across the EU. In Table 1 below, Quintile 1 on the left represents the bottom fifth of jobs by pay, Quintile 5 on the right the top fifth. It shows the polarisation of jobs in the UK over 2011-15 and how most jobs created in the bottom quintile are part-time, temporary or self-employment. Without a decent or solid wage floor, one consequence is that it is more difficult for these workers to plan their lives.

Table 1: Net employment change by job-wage quintile, decomposed by employment type, UK 2011-15 (1000s)

Source: Eurofound (2015)

Being in bad jobs is compounded by the lack of opportunity for many of these workers to escape into better jobs. By 2015 just over 10% of the UK workforce was not born in the UK. Further data from Eurofound shows these workers spread across the quintiles over 2011-15, but the largest proportion was employed in the bottom quintile – accounting for just over 20% of workers in this quintile. Across the EU generally, native workers have tended to shift from the lower quintile jobs; by contrast in the UK many native workers continue to work in these jobs. A bad jobs trap thus exists for many UK-born workers which also means that, disproportionality, they work alongside more migrant workers. From their perspective, things are unlikely to get any better any time soon for these UK-born workers.

Theresa May has promised to address the plight of these workers, saying that she is listening to their frustrations. A good place to start would be to introduce polices that offer employment enrichment that improves job quality and provides springboards out of bad jobs.

This blog draws on material from Chris Warhurst’s Accidental tourists: Brexit and its toxic employment underpinnings, Socio-Economic Review, 14(4): 819-825, 2016, and is one of a number of articles in the journal debating the factors associated with Brexit.