IER News & blogs

The Green Industrial Revolution and demand for green jobs - blog by Pauline Anderson*, Jeisson Cardenas Rubio and Chris Warhurst

The UK Prime Minister has proclaimed a Green Industrial Revolution. This revolution will ‘build green jobs and industries of the future’ the Prime Minister stated. The big question is whether there is employer demand for the jobs that will support this revolution. Examining new data on vacancies for green jobs suggests that demand is not growing and that further stimuli and support will be needed to deliver this revolution.

The UK Prime Minister has proclaimed a Green Industrial Revolution. This revolution will ‘build green jobs and industries of the future’ the Prime Minister stated. The big question is whether there is employer demand for the jobs that will support this revolution. Examining new data on vacancies for green jobs suggests that demand is not growing and that further stimuli and support will be needed to deliver this revolution.

The green shoots of revolution

In November 2020 UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson set out his ten-point plan for a Green Industrial Revolution that will, he says, create and support up to 250,000 jobs in the UK. Moreover, these jobs will be high-skill jobs. As is usual with Johnson, the announcement was light on detail. The announcement doesn’t distinguish between support for existing jobs and the stimulation of new jobs. What is claimed is that ‘thousands of new jobs’ will be created across the Midlands, the North East of England and North Wales. The jobs will span across a number of industries, for example: Offshore wind; Hydrogen; Nuclear; Automotive; Maritime; Buildings’ energy efficiency. And with these industries covering much of the UK’s old industrial heartlands, the Green Industrial Revolution will also extend to Scotland, and Yorkshire and the Humber in Johnson’s ‘ambitious plans to level up across the country’.

With many of Johnson’s past announcements being strong on rhetoric and weak on delivery, not surprisingly, this this one received a mixed response. On the one hand there are the sceptics. Former UK Chancellor Nigel Lawson and climate change sceptic for example, argued it was a distraction ploy to divert attention from the current Covid crisis. At best it is the usual Johnsonian hubris, he suggests. On the other hand, more sensible commentators, such as the Resolution Foundation, largely agree with the Prime Minister. To beat off rising unemployment, it argues that new jobs need to be created, and jobs that help meet the UK’s net zero targets would be a good place to start.

However one of the recurring problems with translating policy into practice is the frequent disconnection between what government wants to happen and what is happening on the ground. The key issue is whether employers need more green jobs. It is therefore important to know the extent of green jobs in the UK and the level of demand for more of these jobs. Our analysis shows that demand does exist and that, moreover, a good proportion of these green jobs are likely to be high skilled. However, current levels of demand do not indicate a restructuring of the labour market towards green jobs.

Measuring employer demand for (more) green jobs

IER has developed a new and large vacancy database drawn from the main UK job portals using web scraping techniques. It includes around 2m observations since February 2019. The vacancy data was then coded to the most recent Office for National Statistics and international standard occupational and industrial classifications (ISCO and ISIC respectively) using IER’s unique CASCOT coding tool. With this new dataset, we can track changes to employer demand for green jobs.

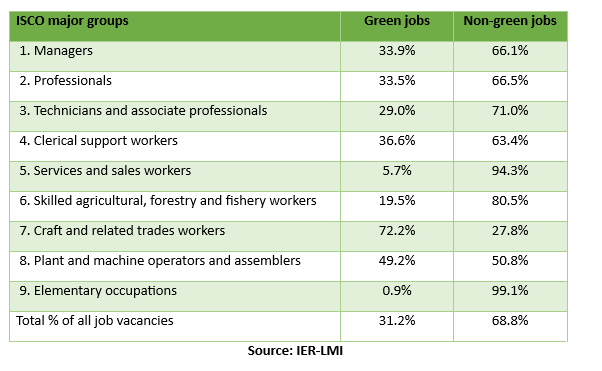

The data from February 2019 to October 2020, just before Johnson’s announcement, shows that there are already many green jobs. Around 31% of all jobs can be classed as green jobs. These jobs don’t just include home insulation fitters and wind turbine engineers but support roles such as lawyers and accountants and cut across industries such as information technology and motor vehicle maintenance and repair. Many of these green jobs are already high skill. Around a third of high-skilled managers and professionals have green jobs, see Table 1 below. However, the same is true of clerical workers. Conversely, more than two-thirds of intermediate-skill craft workers have green jobs and around half are factory operatives and assemblers.

This imbalance between high- and lower-skill green jobs should not be dismissed derisively. After all, it is craft and factory workers who make things such as wind turbines and electric engines for cars and who would be insulating our homes and public buildings.

Table 1: Percentage of green jobs vacancies by major ISCO occupational groups

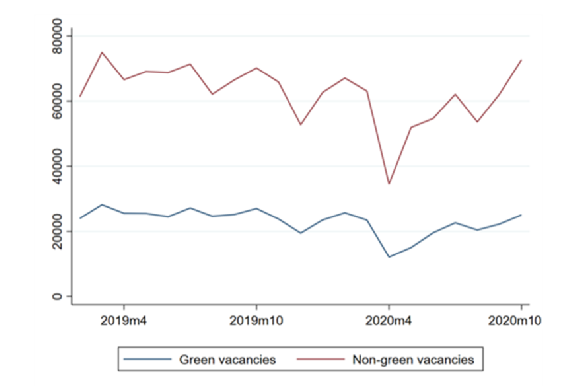

Looking at the number of green job vacancies over this period (see Figure 1 below), two points are worth noting. First, the pattern of demand follows the general labour market cycle. When Covid hit the economy, green job vacancies fell along with non-green job vacancies. As the first lockdown eased, vacancies for both types of jobs rose, though for green jobs more slowly. Second, although there was considerable relative fluctuation in green job vacancies, there has been no proportionate increase in the demand for green jobs compared to non-green jobs. In 2019 (Feb-Oct), the percentage of green jobs was around 32% of total jobs; in 2020 (Feb-Oct) it was approximately 30%. The best that can be said is that demand is relatively stable.

Figure 1: Green and non-green job vacancies evolution

Source: IER-LMI

In short, the data shows that the UK already has many green jobs, many of which are good jobs. However there is no new surging demand from employers to create more of these jobs. There is little evidence that the path to net zero is strewn with hundreds of thousands of new green jobs. What is more, green job vacancies, as a proportion of all job vacancies, are currently shrinking, not growing. Policy therefore needs to focus on stimulating and supporting demand if the Green Industrial Revolution is to happen.

Encouraging green jobs growth

The UK Prime Minister has lauded the creation of ‘good’ jobs (i.e. high-skill jobs) and our analysis suggests that many green jobs are indeed ‘good’ jobs if skill level is the proxy for job quality. Ensuring that good jobs are part of the Green Industrial Revolution will be important. The UK already has too many poor-quality jobs. However, additional markers of the quality of green jobs are needed e.g. pay, training and contract types. ‘Making our homes, schools and hospitals greener, warmer and more energy efficient’, as Johnson proposes, may well stimulate demand for green jobs but what happens once all the heat pumps and smart meters have been fitted, will these jobs disappear? Ensuring the sustainability of new good green jobs will be important.

We need to know more about these jobs – not just whether they have short or longer-term employment contracts. Jobs in the green industries have already been lost during the pandemic. We need to monitor net job creation. Jobs can shift from ‘sunrise’ to ‘sunset’ industries and within businesses. Many displaced oil and gas workers, for instance, have moved into renewables, and greening pressures on businesses reduces demand for workers in some operational areas and increases demand in other operational areas. We need to know which jobs are being created, lost or simply re-assigned.

We also need to know where green jobs will be created. Green job creation for the UK does not necessarily mean more jobs in the UK. The UK Government’s Scottish Secretary, Alister Jack, was grilled in the UK Parliament last year by Tony Lloyd MP on this issue. ‘The Secretary of State will recall that, when EDF was given a licence to develop the wind farm at Neart na Gaoithe, 10 miles off the Fife coast, there was a commitment that 1,000 jobs would be created in making the jackets for the wind turbines. Can he tell the House how many jobs have been created?’ When Jack conceded that he did not know the answer, Lloyd replied: ‘I will tell the Secretary of State how many jobs were created: 1,000 - in Indonesia’. Offshoring green jobs will not aid the Prime Minister’s regional levelling up ambitions within the UK.

We also need to know where green jobs will be created. Green job creation for the UK does not necessarily mean more jobs in the UK. The UK Government’s Scottish Secretary, Alister Jack, was grilled in the UK Parliament last year by Tony Lloyd MP on this issue. ‘The Secretary of State will recall that, when EDF was given a licence to develop the wind farm at Neart na Gaoithe, 10 miles off the Fife coast, there was a commitment that 1,000 jobs would be created in making the jackets for the wind turbines. Can he tell the House how many jobs have been created?’ When Jack conceded that he did not know the answer, Lloyd replied: ‘I will tell the Secretary of State how many jobs were created: 1,000 - in Indonesia’. Offshoring green jobs will not aid the Prime Minister’s regional levelling up ambitions within the UK.

In this respect, and more broadly, there needs to be scrutiny and accountability of licences and business contracts awarded by government to private firms in terms of where business will be done. These contracts might also include job creation targets, particularly in disadvantaged localities. Analysis at the English regional level, as well as for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will be essential to ensuring that the Prime Minister’s levelling up agenda results in concrete and beneficial outcomes that deliver deep-rooted change in areas of industrial decline and disadvantage.

The Prime Minister’s levelling up agenda needs to extend to people as well as places. Understanding who is getting the good green jobs is important for ensuring a ‘just’ and inclusive transition. Women, young people, the long-term unemployed and workers trapped in low-skilled, low-paid work are especially at risk of being left behind and supporting them to break out of the bad jobs trap and get into these better jobs should be a priority. Our analysis shows that there are a range of green jobs by skill level. Not all will be high skill, suggesting that there will be opportunities for all if the right all-age career guidance and training opportunities are available.

The Prime Minister’s levelling up agenda needs to extend to people as well as places. Understanding who is getting the good green jobs is important for ensuring a ‘just’ and inclusive transition. Women, young people, the long-term unemployed and workers trapped in low-skilled, low-paid work are especially at risk of being left behind and supporting them to break out of the bad jobs trap and get into these better jobs should be a priority. Our analysis shows that there are a range of green jobs by skill level. Not all will be high skill, suggesting that there will be opportunities for all if the right all-age career guidance and training opportunities are available.

Linked to this last point, creating and supporting 250,000 green jobs requires a net-zero ready skills system, within which good quality labour market information is key. This information should track changes over time. We would expect the proportion of green jobs to increase on the path to net zero – as green jobs become more in demand and non-green jobs, in some industries at least, to decline. This information should then be used to help anticipate and support training, retraining and upskilling needs. To this end, as part of its Climate Emergency Skills Action Plan, the Scottish Government is setting up a Green Jobs Skills Hub to gather and cascade the intelligence across the skills system on the numbers and types of green jobs that will be needed over the next 25 years.

Translating policy into practice

To ensure that the critics are wrong and that the Green Industrial Revolution is realised, the UK Government needs to translate policy into practice. Based on our analysis, we suggest the following as a minimum:

1. Producing a Workforce Plan for the Green Industrial Revolution

1. Producing a Workforce Plan for the Green Industrial Revolution

Developed by a Leadership Group, this Plan will provide the blueprint for job creation and support all workers to get into, stay in and progress within the good green jobs. It should be premised on creating good jobs and include standards of what good green jobs look like. It should also be based on an agile skills system that can adapt to emerging labour market needs. Development and implementation of this Plan requires input from all stakeholders for it have relevance and legitimacy.

2. Establishing green jobs/industries observatories

Similar to the Hub in Scotland, these Observatories should operate for all main English regions as well as Wales and Northern Ireland. They would monitor and evaluate green labour market and business developments and needs, including job quality, and be a portal of information and intelligence for stakeholders. The information will also inform the progress of the Workforce Plan. Observatories would be able to identify 'bottlenecks', and work with regional/national stakeholder groups to support innovative, flexible and timely interventions in the labour market such as new training needs.

3. Using public procurement contracts to ensure jobs are created and stay in the UK target regions

Government needs to get serious about stimulating green job creation. In addition to short term tax breaks to encourage all firms to join the Green Industrial Revolution, net zero related contracts awarded by government to firms, for example, should include a clause to promote jobs within the UK, whether retrofitting social housing and public buildings or building electric automotive batteries. In addition, the government needs to ensure that these firms offer job access opportunities for 'disadvantaged' regions and types of workers. Developing an evidence base of what works in this respect from local, national and international examples would be helpful.

4. Improving the information database for employment in the green industries

Whilst the vacancy data scraping method that IER has developed is extremely useful, the information that it generates needs to be supplemented with other approaches to understand what else is happening to green jobs growth. For example, having data available through the soon-to-be-revamped UK Labour Force Survey that enables identification of green jobs lost and structural changes to the UK labour market as existing brown jobs are lost or go green, green jobs are created and, just as importantly, existing green jobs are lost.

* Dr Pauline Anderson, Strathclyde Chancellor's Fellow, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow