IER News & blogs

Teleworking in Europe before and during the pandemic

In a recent webinar, hosted by the Productivity and the Futures of Work GRP at the University of Warwick and facilitated by IER’s Professor Chris Warhurst, Dr Enrique Fernández-Macías of the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission examined how Covid-19 had changed the profile of the teleworker and what it meant for the future of work. The recording of the webinar is accessible via the replay link.

In a recent webinar, hosted by the Productivity and the Futures of Work GRP at the University of Warwick and facilitated by IER’s Professor Chris Warhurst, Dr Enrique Fernández-Macías of the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission examined how Covid-19 had changed the profile of the teleworker and what it meant for the future of work. The recording of the webinar is accessible via the replay link.

Measuring the share of workers in work-from-home and close personal proximity occupations in a developing country – Blog by Jeisson Cardenas Rubio and Jaime Montana Doncel*

The COVID-19 pandemic and its social distancing measures have brought unprecedented socio-economic challenges worldwide. One of the most urgent questions is how the labour force will be affected by the pandemic. The answer to this question will have considerable impact on the countries’ productivity, poverty and unemployment rates, etc. Consequently, the measurement of jobs, which can be performed without increasing the risk of contagion, has become a priority in the world. Given rich sources of information such as the Occupational information network (O*NET), more advanced countries such as the United States (U.S.) have started to estimate the number of jobs that can be performed at home (teleworkable jobs) or are at higher risk of contagion because their tasks involve close proximity with others (Dingel and Neiman, 2020; Mongey and Weinberg, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic and its social distancing measures have brought unprecedented socio-economic challenges worldwide. One of the most urgent questions is how the labour force will be affected by the pandemic. The answer to this question will have considerable impact on the countries’ productivity, poverty and unemployment rates, etc. Consequently, the measurement of jobs, which can be performed without increasing the risk of contagion, has become a priority in the world. Given rich sources of information such as the Occupational information network (O*NET), more advanced countries such as the United States (U.S.) have started to estimate the number of jobs that can be performed at home (teleworkable jobs) or are at higher risk of contagion because their tasks involve close proximity with others (Dingel and Neiman, 2020; Mongey and Weinberg, 2020).

Generating statistical data for Colombia

Less advanced countries such as Colombia (where unemployment and informality rates are high - around 10.5% and 46.2%, respectively in 2019) face huge challenges in making such estimations. In these countries, good labour market information is scarce (Cardenas, 2020). To answer the labour force question for Colombia, we have adapted different international work-from-home and proximity measures and estimated the proportion of workers in the corresponding groups according to the Colombian context. With these results, Colombian policymakers have labour market information to make prompt and data-driven decisions. Moreover, this exercise provides evidence that national surveys in developing countries (e.g. household surveys) and international references such as the O*NET can be combined to produce consistent indicators to reduce the impact of the COVID-19 in the labour market.

Thanks to the work conducted by Cardenas (2020) in coding Colombian job titles in the household survey to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO 08) at four-digit level for the first time and the taxonomies proposed by Dingel and Neiman (2020) and cross-walks between ISCO and SOC-O*NET, based on the 2018 Standard Occupational Classification, we could map the work-from-home occupations in Colombia. We recognise that technologies, skills and tasks required in developing countries might differ from the ones demanded in more advance countries. Thus, work-from-home occupations in the U.S. might not coincide with work-from-home occupations in Colombia. To address this issue, we also adapt the work by Saltiel (2020) who estimated the share of jobs that can be done from home in ten developing countries (including Colombia) with the Skills Toward Employability and Productivity (STEP) survey. This information provides an alternative indicator to measure teleworkable occupations.

How many jobs can be done from home?

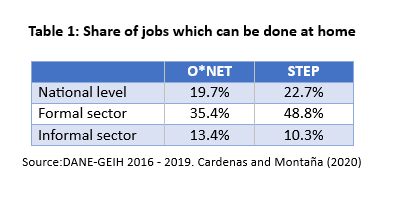

Table 1 shows the proportion of jobs that can be done at home. Based on Dingel and Neiman’s (2020) definition, 19.7% of the total workers in Colombia can perform their jobs at home. However, this proportion considerably differs when the population is divided into formal and informal workers. Around 35.4% of formal workers can telework, while only 13.4% of informal workers can do their jobs at home.

Table 1 shows three relevant points: (1) the share of Colombian workers who can work at home is relatively low compared with the U.S. (around 37%, Dingel and Neiman, 2020); (2) the informal sector might be more affected by social distancing measures because only between 13.4% and 10.3% of these workers can work at home; (3) importantly, definitions based on STEP (Saltiel, 2020) and on O*NET (Dingel and Neiman, 2020) produce similar results. Indeed, for 84.3% of total workers in Colombia, the O*NET and STEP taxonomies categorise them in the same group (non-teleworkable or teleworkable). Thus, the results from O*NET do not drastically differ from other sources of information, and instead, they add more elements to analyse the labour market in developing countries.

Who works in work-from-home occupations?

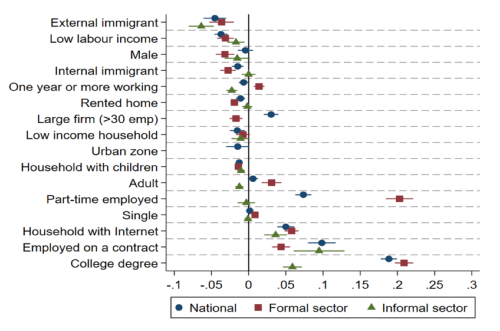

Additionally, we estimate the characteristics of workers in work-from-home occupations. As shown in Figure 1, workers with a college degree, (written) employment contract or living in households with an internet connection are more likely to have work-from-home occupations. In contrast, male immigrants and workers with a low income (below the minimum wage) are less likely to work at home. In summary, Figure 1 reveals who are the more (or less) vulnerable workers by “stay at home” public policy measures.

Figure 1: Characteristics of workers in teleworkable occupations

Source: DANE-GEIH 2016 - 2019. Cardenas and Montaña (2020)

How many work in close personal proximity occupations?

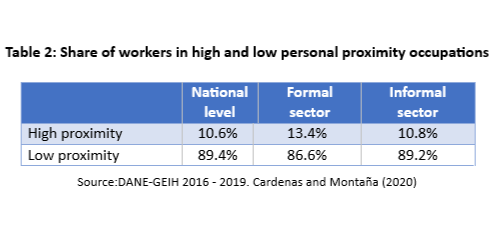

To answer the question about the share of workers which can continue working without increasing the risk of contagion, we follow Leibovici et al. (2020) who define a high-proximity occupation when, according to the O*NET, its tasks involve close (less than an arm length of distance) physical proximity to other people. Our results for Colombia in Table 2 show that 13.4% and 10.8% of formal and informal workers, respectively, perform activities that involve close personal proximity with others. This result reveals that at least 10.6% of workers at the national level need to have the proper protective equipment and precautions while they are performing their jobs.

Who works in close personal proximity occupations?

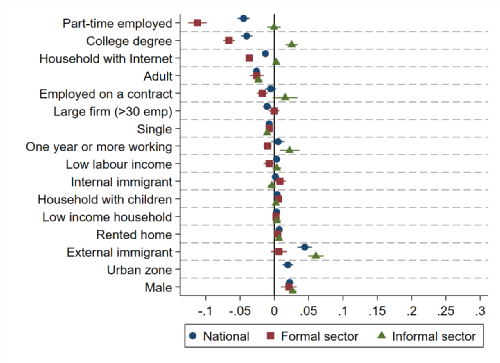

Finally, we estimate the characteristics of workers in close personal proximity occupations. Figure 2 shows that part-time employees, workers with a college degree and those living in a household with an internet connection are less likely to have jobs in close personal proximity occupations. In contrast, male immigrants and urban workers are more likely to work in close personal proximity occupations. Consequently, these workers are at a higher risk of contagion in Colombia.

Figure 2: Characteristics of workers in high personal-proximity occupations

Source: DANE-GEIH 2016 - 2019. Cardenas and Montaña (2020)

Conclusion

We reveal that informal, low educated and immigrant workers are those most affected by social distancing measures and that they also tend to be at higher risk of contagion of COVID-19. Additionally, we show that international resources such as the O*NET can be used in a developing country without adding considerable “noise” to the labour market analysis. We are convinced that these kinds of studies will considerably help policymakers to protect workers, especially those with higher economic and health risks.

References

Cárdenas, J. (2020, forthcoming). A web-based approach to measure skill mismatches and skills profiles for a developing country: the case of Colombia. Colombia Científica. Library Catalogue: https://alianzaefi.com/.

Cárdenas, J. & Montaña, J. (2020, forthcoming). Measuring the share of workers in work-from-home and close personal proximity occupations during the Coronavirus crisis in a developing country. Colombia Científica. Library Catalog: https://alianzaefi.com/.

DANE (2019). Empleo Informal y Seguridad Social. Retrieved April 28, 2020 http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/mercado-laboral.

Dingel, J. I. & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Leibovici, F., Santacreu, A.M. & Famiglietti, M (2020). Social Distancing and contact-intensive occupations j St. Louis Fed. Library Catalog: www.stlouisfed.org.

Mongey, S. & Weinberg, A. (2020). Characteristics of workers in low work-from-home and high personal proximity occupations, BFI White Paper.

Saltiel, F. (2020). Who Can Work From Home in Developing Countries?

* Jaime Montana Doncel is a PhD candidate at the Paris School of Economics and Università degli studi di Torino.

Managing flexible working: learning to cope with the new normal? Blog by Professor Clare Lyonette and Beate Baldauf

The ramifications of the current Covid-19 crisis are likely to be felt in all areas of our lives. Many of the future projections we hear and read about every day are understandably stark and doom-laden, but are there any potentially positive implications of the pandemic?

The sharp rise in the number of people being required to work solely from home during the current crisis has led to a surge in interest in the longer-term outcomes of wider flexible working, with many researchers in the UK and elsewhere discussing Covid-19 as a possible turning point in our attitudes towards greater flexibility (Moen, 2020; Slaughter and Bell, 2020; Bevan, 2020).

Before Covid-19 hit the headlines, we conducted a review of relevant literature since 2008 (Lyonette and Baldauf, 2019) for the Government Equalities Office to identify what evidence exists that family-friendly working policies and practices (FFWPs) benefit or disadvantage employers, and to identify any good practice from employer-led interventions in implementing FFWPs.

In response to the current crisis, many managers are having to deal with staff working from home, some of whom have small children or elderly relatives to care for during the day. Researchers have argued for years that managers, especially those with daily responsibility for staff, are key to the success of flexible working (Lewis, 2003). Here we offer some insights into the known benefits of flexible working and make some recommendations, based on tried and tested interventions in different organisational contexts, to support employers and managers in negotiating widespread flexible working through the crisis and beyond.

Flexible working – the benefits and disadvantages for employers

The majority of research highlights positive organisational outcomes from implementing a broad range of FFWPs, including cost savings, better productivity, improved recruitment and retention and reduced absenteeism. Cost savings can arise from both direct and indirect effects, such as improved employees’ work-life balance and reduced stress leading to reduced absenteeism and turnover, or perceptions of a positive workplace culture leading to greater commitment, loyalty and productivity. These indirect effects are harder to measure, e.g. isolating these effects from other individual and organisational-level factors is difficult, and a lack of clear evidence may deter some employers from implementing FFWPs. Of course, there are some negative aspects to certain types of flexible working for individual employees. For example, enforced homeworking can have an adverse effect: many employees do not have the space to work permanently from home or in a remote location, even with advanced IT options, and others prefer the social aspects of a workplace setting (Lyonette et al., 2017). Employers should be aware of the potentially negative effects this may incur over the longer–term (e.g. reduced wellbeing and loyalty to the organisation may lead to reduced productivity, which will serve to deplete any savings made from reduced office space and resources). Taken together, however, the evidence points to positive impacts for both employers and employees. The types of FFWPs offered may differ according to the organisation and the requirements of particular job types (e.g. customer-facing roles, emergency services, etc.) but introducing a more flexible workplace culture would appear to have wide-ranging benefits.

Lessons learned from successful interventions

So what lessons can be learned from successful interventions in implementing flexible working prior to the Covid-19 pandemic? Here we draw out recommendations to help organisations move towards more flexible working.

- Encourage transparency among managers, flexible workers and other colleagues: Senior management and line managers need to be trained in managing flexible workers, especially in the current crisis. The roll-out of widespread FFWPs requires ongoing monitoring and updating as flexible working arrangements can affect other team members, as well as managers. Open dialogue is important in creating a trusting environment, one in which flexible workers and their colleagues can voice concerns and discuss positive ways forward (not everyone will prefer to work from home in the longer-term).

- Introduce and promote a wide range of FFWPs: While some FFWPs may prove to have better organisational outcomes for different employers, the evidence did not allow for the identification of ‘better’ or ‘worse’ individual policies and practices. Employers are encouraged to introduce trial periods of a broad range of FFWPs to identify what works best.

- Disseminate good practice: Employers need to understand and accept the business case for flexible working and can learn from good practice examples of employers and employees operating in a similar environment. Flexibility ‘champions’ (preferably senior managers) can promote the case for flexibility within their own organisation but also in others. Being seen as a pioneer in flexible working, and also doing the right thing for employees, can convey a powerful message to potential employees, as well as to existing staff. This may have the knock-on effect of increasing morale and job satisfaction, as well as recruiting and retaining valued employees after the current crisis.

- Develop a positive workplace culture: The availability of FFWPs within an organisation is not a guarantee that employees will feel able to make use of them. A positive workplace culture, one in which management is supportive of flexible working and which encourages take-up of flexible working, is required, especially at a time when workers may feel vulnerable to job losses. Senior management can play an important role, signalling to line managers and to other employees that flexible working is normalised within an organisation.

- Trial and measure flexible working over a reasonable time period: Any widespread implementation of flexible working should be trialled and measured for both employee and employer outcomes over a reasonable period of time. It is unlikely that outcomes such as productivity and turnover can be properly assessed over a short period and other factors potentially affecting such outcomes should also be considered (e.g. the external labour market and the impact of Covid-19, the introduction of new IT systems, etc.).

- Think in the longer-term: It is recognised that flexibility can be employer- or employee-led and, in difficult economic times such as the one created by Covid-19, it is perhaps unsurprising that employer-led flexibility is prioritised over the needs and wellbeing of employees. However, employers need to remain focused upon the wellbeing of their employees. An upturn in the labour market may encourage valued employees to leave if unsatisfied, leading to high turnover costs and a loss of vital skills.

- Challenge gendered attitudes and approaches towards flexible working: While FFWPs would appear to be beneficial to many women, especially those with caring responsibilities, they also have the potential to work against gender equality. Any perceptions of flexible working as a ‘woman’s issue’ should be challenged and all employees need to be offered and encouraged to take up FFWPs. Male and female role models working flexibly can demonstrate to others that it can be done successfully. Any training and development opportunities need to be offered equally to men and women, working flexibly or not, in order to reduce any inequalities in promotion and progression.

History will show whether Covid-19 proves to be a turning point in our attitudes towards greater workplace flexibility.

Find further outputs from the Government Equalities Office programme of research, and its wider focus upon closing the gender pay gap, here.

IER report published by Government Equalities Office on why employers should introduce wide-ranging family-friendly working policies

A new report, 'Family friendly working policies and practices: Motivations, influences and impacts for employers', led by IER's Professor Clare Lyonette and Beate Baldauf , and commissioned by the Government Equalities Office (GEO), is the outcome of a series of GEO funded research projects aiming to support employers in closing the gender pay gap.

Key recommendations for employers include:

● Introduce and promote a wide range of flexible working policies and practices

● Disseminate good practice

● Develop a positive workplace culture

● Encourage transparency among managers, flexible workers and other colleagues

● Trial and measure flexible working over a reasonable time period

● Think in the longer-term

● Challenge gendered attitudes and approaches towards flexible working.

Commenting on the findings, Professor Lyonette said:

‘The link between family-friendly working policies and practices and the gender pay gap may not be immediately obvious. We highlight evidence which shows that offering and promoting flexible working to both women and men can create a positive workplace culture, benefiting both employees and employers. Ultimately this can lead to greater gender equality and a reduced pay gap but only if flexible working is not seen as a women's issue'.

The full report can be accessed here and the summary report here.

New book on work-life balance in austerity and beyond

Dr Clare Lyonette is the co-author of a new book which has just been published by Routledge, including chapters from academics and practitioners on the impact of the recession and austerity policies in work-life balance policies and practices, particularly how they affect our ability to achieve the triple agenda of individuals' work-life balance and wellbeing, workplace effectiveness and social justice.

Dr Clare Lyonette is the co-author of a new book which has just been published by Routledge, including chapters from academics and practitioners on the impact of the recession and austerity policies in work-life balance policies and practices, particularly how they affect our ability to achieve the triple agenda of individuals' work-life balance and wellbeing, workplace effectiveness and social justice.

A chapter co-authored by Clare highlights recent research on flexible working arrangements and how they are being used by public sector organisations in the UK to manage austerity. It also discusses some implications of these developments in 'new ways of working'

Lewis, S., Anderson, D., Lyonette, C., Payne, N. and Wood, S. (2016) Work-Life Balance in Times of Recession, Austerity and Beyond. London and New York: Routledge.