IER News & blogs

What might happen to Apprenticeships in England during the Covid-19 economic downturn? Blog by Terence Hogarth and Lynn Gambin*

Trends to date

If one compares the number of apprenticeship starts in April 2019 to one year later, it is possible to gain an indication of the potential fall in the number of apprentices (see Figure 1). In April 2020, the total number of apprenticeship starts was one third of that in April 2019. Should this level of decline persist, this would indicate that 2020 will see around 200,000 fewer people starting apprenticeships than in 2019. In addition to fewer starts, there is a risk that existing apprentices might be unable to complete their training if they are made redundant.

Figure 1: Apprenticeship starts in April 2018, 2019 and 2020

Source: Department for Education Monthly Apprenticeships Statistics Data

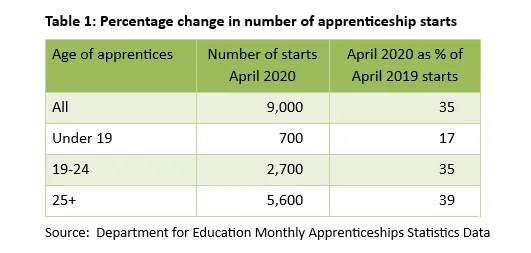

Table 1 illustrates the uneven impact of the economic downturn on apprenticeship starts by age group. The number of starts by apprentices under 19 years of age in April 2020 was equal to 17 per cent of the level observed in April 2019. The April 2020 number of starts as a percentage of those in 2019 was 39 per cent for those aged 25 years and over, and 35 per cent for 19-24 year olds (see Table 1). While all age groups are affected, younger people appear to fare worst.

It may be that interventions of one kind or another will ensure that the fall in the number of apprentices will not be as bad as the simple extrapolations presented here suggest. Countries across Europe are hurriedly trying to find the means to prop up their apprenticeship systems. This reflects not only the urgency attached to making sure that existing apprentices complete their training, but also the need to both find places for those exiting compulsory education this year and to protect future skills supply.

Government support for VET during the crisis

On 8th July 2020 the Government announced a range of measures, supported by sizable public funding, designed to secure young people’s access to vocational education and training. These measures included:

- bonus payments to businesses in England to take on new apprentices in the next six months (£2,000 for apprentices aged 16 to 24 and £1,500 for those aged 25 and over. This bonus is on top of the current £1,000 incentive already in place for employers to take on 16 to 18 year old apprentices, and those under 25 years of age with an education, health and care plan;

- a £2 billion Kickstart Scheme in Great Britain paying the wages of 16 to 24 year old universal credit claimants to take six-month work placements;

- tripling the scale of “proven” traineeships in 2020-21 supported by £111 million of investment.

The emphasis in these announcements is on young people as their economic prospects are most at risk from the current health crisis. Whether these measures will prove sufficient and whether more intervention is required, only time will tell. But they mark a substantial intervention into the provision of training of young people by Government.

Apprenticeships the world-over are recognised as being particularly effective in helping people make the transition from school to work and, at the same time, matching the supply of skills to the needs of the labour market. It is for this very reason that policy makers have persisted with this form of training in England even though it has proved to be an uphill struggle at times to persuade employers to provide apprenticeship places.

Avoiding the mistakes of the past

If the bounce back from the recession is relatively rapid, then all that may be required is short-term assistance to ensure that a sufficiently large number of apprenticeship places are available. A wage subsidy may be one means by which this can be achieved. But if the recession proves to be more protracted, then a more root and branch review of vocational education and training may be required. No apprenticeship system worth the name can withstand year-on-year calamitous falls in the number of apprentices. It may be that T-Levels can pick up the slack. The combination of classroom based training allied to a substantial amount of time spent practising skills in the workplace potentially provides a credible alternative to apprenticeships, especially when relatively few of the latter are available.

A more damaging outcome, should any recession prove protracted, could result from ad hoc policy-making. If a cohort, or successive cohorts, of young people are funnelled into makeshift training programmes in order to avoid levels of youth unemployment last seen in the 1980s and 1990s, or even higher, then nothing will have been learnt from the policy mistakes associated with the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) and Youth Training Scheme (YTS). The failings of these programmes to deliver training which conferred economic value on their participants led to the establishment of the publicly funded apprenticeship programme in England in 1994.

A more damaging outcome, should any recession prove protracted, could result from ad hoc policy-making. If a cohort, or successive cohorts, of young people are funnelled into makeshift training programmes in order to avoid levels of youth unemployment last seen in the 1980s and 1990s, or even higher, then nothing will have been learnt from the policy mistakes associated with the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) and Youth Training Scheme (YTS). The failings of these programmes to deliver training which conferred economic value on their participants led to the establishment of the publicly funded apprenticeship programme in England in 1994.

It would be a pity to make the mistakes of the past once again by resorting to ad hoc policy responses which have a whiff of YOPS/YTS about them. There is a need to maintain access to high quality structured training opportunities so that the current cohort of would-be apprentices are not disadvantaged compared with their counterparts in the past or their likely ones in the future. This is why public support for programmes which provide high quality training opportunities, be it through apprenticeships, T-levels, or something else, is so important at the current point in time. It will not only safeguard young people’s futures, but also the future skill needs of the economy.

* Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Memorial University Newfoundland, St Johns, Canada

Interested in Terence Hogarth’s expert comment on the Kickstart scheme for 16-24 year olds? Read more here.

Interested in other blogs? Read more here