IER News & blogs

What is the future of youth skill-building in developing countries in the post Covid-19 era? Blog by Dr Sudipa Sarkar and Bhaskar Chakravorty

Unemployment and scarcity of jobs have long been important concerns for policymakers in developing countries (World Bank, 2012). These issues are crucial for India as the country is home to the world’s largest population of young people ready to participate in the labour force (UNFPA report, 2019). The current situation caused by the Covid-19 outbreak and the subsequent countrywide lockdown is certain to affect employment levels in the country, especially as India has a large informal economy, which is currently bearing the major brunt of the lockdown. In this context, targeted Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs), which have been historically used to cushion the economic shock of such global crises in developing countries, can play an important role (Cazes, Heuer, & Verick, 2011; Imbert and Papp, 2015; World Bank, 2012).

Unemployment and scarcity of jobs have long been important concerns for policymakers in developing countries (World Bank, 2012). These issues are crucial for India as the country is home to the world’s largest population of young people ready to participate in the labour force (UNFPA report, 2019). The current situation caused by the Covid-19 outbreak and the subsequent countrywide lockdown is certain to affect employment levels in the country, especially as India has a large informal economy, which is currently bearing the major brunt of the lockdown. In this context, targeted Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs), which have been historically used to cushion the economic shock of such global crises in developing countries, can play an important role (Cazes, Heuer, & Verick, 2011; Imbert and Papp, 2015; World Bank, 2012).

In India, governments have long engaged in a variety of ALMPs that directly intervene in the labour market (from both demand and supply sides) with the aim of reducing unemployment. Demand side interventions include the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) and supply side interventions comprise several skill-training programmes that aim to increase the skills of the workforce and match them to appropriate jobs. Several skill-building programmes run by the government of India particularly target unemployed rural youth from poor families and aim to provide them with salaried employment after training completion. One such programme, launched in 2014, is the "Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushal Yojana"(DDU-GKY hereafter) which set out to “transform rural poor youth into an economically independent and globally relevant workforce” (DDU-GKY Programme Guidelines, 2016). In this particular programme, skill development is implemented through a Public-Private Partnership mode (PPP model), where registered private sector partners (called programme implementing agencies or PIAs) plan and implement skills training and job placements (DDU-GKY Policy Guidelines, 2016).

Ongoing IER research on a skill-building programme

Before the virus outbreak and lockdown, we, a team of researchers at the IER started studying the effectiveness of this programme in building skills that can help provide employment opportunities to young people in rural Bihar and Jharkhand, two of the poorest states in India. Though our study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), focuses on only one scheme, our findings will have wider applicability as similar programmes are being implemented in other parts of the country.* Examples of such programmes are, the '"Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana" and area-specific programmes such as "Himayat" (in Jammu and Kashmir), and "Roshni" (in 27 left-wing districts across nine states).

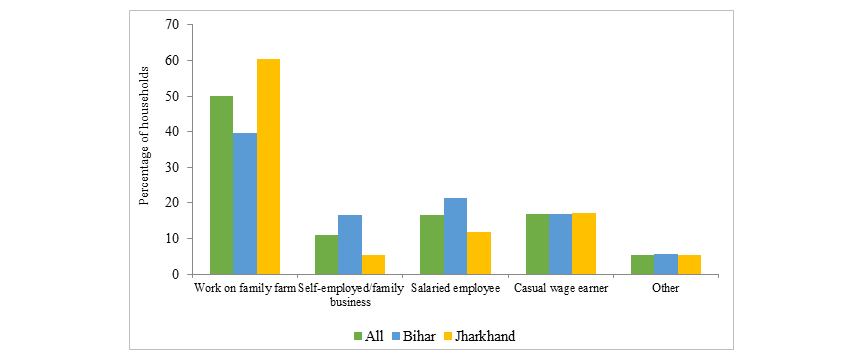

Our baseline sample consists of 1769 young people, mostly from poor households (83% with below poverty line card), unemployed (only 12% did some paid work before taking the training), and with secondary or higher secondary school education (around 85%). About half of the participants report that they ‘work on a family farm’ as the main occupation of the head of their household (Figure 1). The percentage working on a family farm is higher in Jharkhand (60%) compared to Bihar (39%) as many households in Bihar (around 40%) do not own any agricultural land, which explains the historic trend of mass migration to other states for employment, predominantly in the informal sector. Only 16.6% of the participants report ‘salaried employment’ as the main occupation of their household heads, with the figure even lower in Jharkhand (at 12%). According to national statistics, 70 to 80% of non-agricultural employment in Bihar and Jharkhand is in the informal sector (National Sample Survey, 2012). Therefore, casual wage work in the informal sector is probably the only option for the households without any agricultural land. In this context the DDU-GKY training programme (and others like it) may lead to salaried wage employment in the formal sector for this vast workforce, which would otherwise be casual-wage workers or the disguised unemployed in agriculture.

Figure 1: Main occupation of household head as reported by the training participants

Source: IER-XISS baseline survey, 2019-20.

The impact of Covid-19 and lockdown on skill-building programmes

The DDU-GKY scheme in our two study states, Bihar and Jharkhand, mostly consists of residential training, where the participants from rural areas stay on campus or in the accommodation provided by the training centres/PIAs. The training centres are also located in cities or towns where the risk of the virus spreading is much higher. Given the outbreak and subsequent lockdown on 24th March 2020, all training centres closed and participants were sent back to their native villages. Those who finished training and were placed by the PIAs had returned to their native villages or were stuck in different states where they had been working.

One of the major challenges that DDU-GKY will encounter in the post-Covid era is ensuring that participants who were sent home will return to the training centres to continue their training and encouraging others to enrol for training in the near future. In the absence of any data yet collected in post-lockdown, we can only raise questions and conjecture about the post-lockdown period operation of these programmes. These questions include:

One of the major challenges that DDU-GKY will encounter in the post-Covid era is ensuring that participants who were sent home will return to the training centres to continue their training and encouraging others to enrol for training in the near future. In the absence of any data yet collected in post-lockdown, we can only raise questions and conjecture about the post-lockdown period operation of these programmes. These questions include:

1. Is it possible to continue training the unemployed rural youth by providing them with residential training in urban cities? Once the lockdown is lifted and training centres start to operate in cities, young people from rural areas are likely to feel apprehensive about coming to cities and large towns to train. Cities have been most affected by the virus outbreak and returnees from cities have been stigmatised and, in some places, have not been allowed to enter their native villages.

2. Is it possible for the PIAs to provide salaried employment to the poor unemployed youth after training completion? It is also uncertain whether the PIAs will be able to provide job placements to the training participants in the post Covid-19 era. As economies across the world are likely to go through a severe crisis, demand for labour may fall, resulting in high levels of joblessness.

3. If no salaried employment is available, can the skills built through the programme provide opportunities for self-employment in the post Covid-19 period? Finally, those who completed their training just before the virus outbreak and subsequent lockdown may not have been placed into employment by the PIAs or were placed but lost their jobs due to the lockdown. The question is whether these young people can use the skills built through the programme to make an alternative livelihood to sustain them during the economic crisis. For example, those who enrolled in the course on sewing and tailoring (Industrial Sewing Machine Operation or ISMO) may use the skills learned in the training centre to engage in self-employment in their native village and avoid migrating to cities and towns.

3. If no salaried employment is available, can the skills built through the programme provide opportunities for self-employment in the post Covid-19 period? Finally, those who completed their training just before the virus outbreak and subsequent lockdown may not have been placed into employment by the PIAs or were placed but lost their jobs due to the lockdown. The question is whether these young people can use the skills built through the programme to make an alternative livelihood to sustain them during the economic crisis. For example, those who enrolled in the course on sewing and tailoring (Industrial Sewing Machine Operation or ISMO) may use the skills learned in the training centre to engage in self-employment in their native village and avoid migrating to cities and towns.

Conclusion

We have more questions than answers for now. However, we are currently preparing for midline and follow-up surveys of the same sample of participants who took part in the study before the Covid-19 outbreak and lockdown. Therefore, the survey data will provide us with important findings and will reveal issues on which we can only speculate for now.

* Led by Professor Clare Lyonette, the project is undertaken by a team of researchers at the University of Warwick in collaboration with the Xavier Institute of Social Service (XISS), Ranchi, India and is funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).