IER News & blogs

Caste differences in the acquisition of soft skills among disadvantaged young people in India

Blog by Clare Lyonette, Sudipa Sarkar, Gaby Atfield, Beate Baldauf, Bhaskar Chakravorty and Erika Kispeter

Introduction

‘Soft’ skills are important labour market skills and include social aptitudes, language and communication capability, friendliness and ability to work in a team. Using survey data collected at two time points from a large sample of disadvantaged young people enrolled on a skills training programme in India, we examine whether caste affects initial levels of soft skills, and whether or not these skills can be learned during a relatively short period, providing young people with longer-term opportunities within the labour market.

The DDU-GKY (Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana) is a government-led Indian skills-based training programme that aims to place disadvantaged young people from rural areas into formal paid jobs in manufacturing and services, often located in other states. The programme has a clear mission to engage the most excluded groups. Consequently, it is important to identify the social factors that influence the ability of the programme to achieve its intended outcomes in terms of social development and inclusion, and to assess whether such programmes lead to sustained employment and higher earnings. It is also crucial to examine whether they promote the development of the personal and social capabilities that are linked to the development of employability skills and engagement in society as an equal participant.

Our aim in this research was not to evaluate the overall DDU-GKY programme but to identify factors which will support its success, while simultaneously developing a broader definition of ‘success’, incorporating measures of soft skills gain and the personal efficacy to employ these skills in the workplace and in wider society. ESRC funding, under the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) initiative, allowed us to examine in more detail the aspirations of a large sample of these disadvantaged young people, as well as the challenges and barriers to participating in the training programme.

At the start of the project in 2019, we could not have anticipated the devastating impact of the coronavirus: many young people were sent home mid-training and others returned home after their jobs were discontinued. Our initial research plans had to be revised in light of the pandemic and we focus here on the soft skills learned during the training. The development of soft skills is an often-overlooked outcome of skills training programmes like the DDU-GKY which tend to focus only on getting a job. We also highlight the impact of Covid-19 on participants’ views of their ability and confidence to find a job.

Participants

The study draws from a sample of 1769 trainees enrolled in 65 training batches, randomly selected from 29 training centres in two of India’s poorest states, Bihar and Jharkhand. A batch is a group of students who enrol, have classes and graduate together and participants in all batches lived at the training centre during the training period 1. Although all participants in the training programme came from poor households (as measured by the household being registered as ‘Below Poverty Line’) 2, almost half (49%) of the sample were from Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) and 46% were from Other Backward Class (OBC), which are traditional categorisations of caste groupings in India. SC/ST constitute the most disadvantaged group (including ex-‘untouchables’), whereas OBC participants, along with another group ‘Other Caste’ (OC), are higher in the caste hierarchy.

The study involved two rounds of primary data collection: first, a baseline survey from December 2019 to February 2020 that was conducted within two weeks of the start of training, and an endline survey in August to September 2020 during lockdown in India. The baseline survey was conducted by local data collectors in face-to-face interview sessions, whereas the endline survey was done over the telephone. A total of 1663 of the original 1769 baseline participants were followed up at the endline, representing a response rate of 94%.

The study involved two rounds of primary data collection: first, a baseline survey from December 2019 to February 2020 that was conducted within two weeks of the start of training, and an endline survey in August to September 2020 during lockdown in India. The baseline survey was conducted by local data collectors in face-to-face interview sessions, whereas the endline survey was done over the telephone. A total of 1663 of the original 1769 baseline participants were followed up at the endline, representing a response rate of 94%.

Our measures include four broad categories of soft skills: (1) personal skills or qualities, (2) interpersonal skills, (3) initiation and delivery skills, and (4) work orientation and knowledge of labour market skills3. Here we report on interpersonal skills and their knowledge of the labour market and confidence in finding work.

Caste differences in interpersonal skills

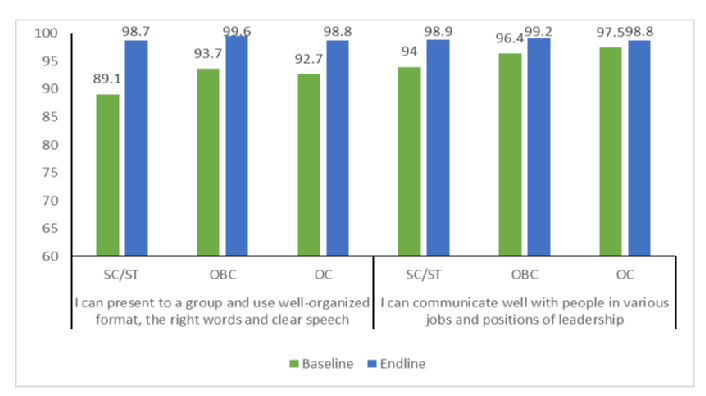

Figure 1 shows that, at the baseline, the vast majority of participants reported an ability to present well, even before the training programme. However, a lower proportion (89.1%) of the SC/ST group (the most disadvantaged caste) reported having this skill at the baseline, compared with 93.7% of OBC and 92.7% of OC castes. For SC/ST participants, this figure climbed to 99% at the endline, the same percentage as the other two caste groups, representing a significant gain.

Figure 1: Interpersonal skills (%)

Similar figures were shown for other interpersonal skills, including an ability to communicate well with people (Figure 1). Although there was not a large increase over time for any of the groups, the rise was greater among SC/ST participants, bringing them to the same level as the other caste groups.

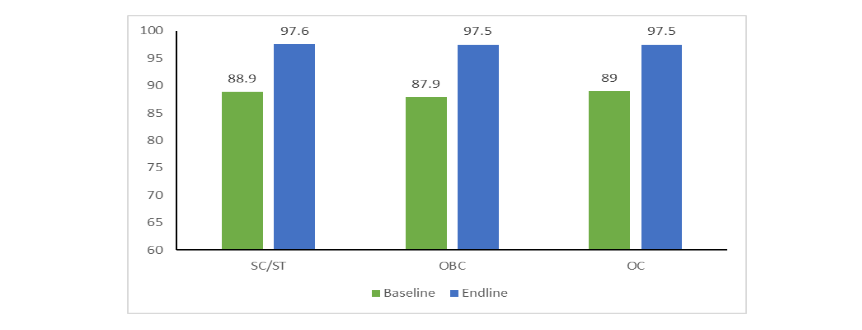

In addition to communication skills, the study also looked at self-efficacy and autonomy, which are important developmental skills for young people. In some cases, the SC/ST group was very similar to the other groups, e.g. Figure 2 shows that 88.9% of SC/ST, 87.9% of OBC and 89% of OC participants said at the baseline that they could make decisions on their own. This rose to over 97% for all three groups at the endline, a significant gain for all groups.

Figure 2: I can make decisions on my own (%)

On no occasion did the SC/ST group report a higher baseline score than the other two groups. Participants from the SC/ST group were also much more likely than the other caste groups, in almost all cases, to disagree that they had these skills at the baseline.

Knowledge of the labour market and confidence in finding work

We then examined participants’ responses over time to questions which included how their skills, qualifications and experience will help them find work and how easy they think it will be to find work. Although these questions did not ask specifically about the impact of Covid at the endline 4, participants and their families were clearly suffering from the financial impacts of not having paid work 5.

We then examined participants’ responses over time to questions which included how their skills, qualifications and experience will help them find work and how easy they think it will be to find work. Although these questions did not ask specifically about the impact of Covid at the endline 4, participants and their families were clearly suffering from the financial impacts of not having paid work 5.

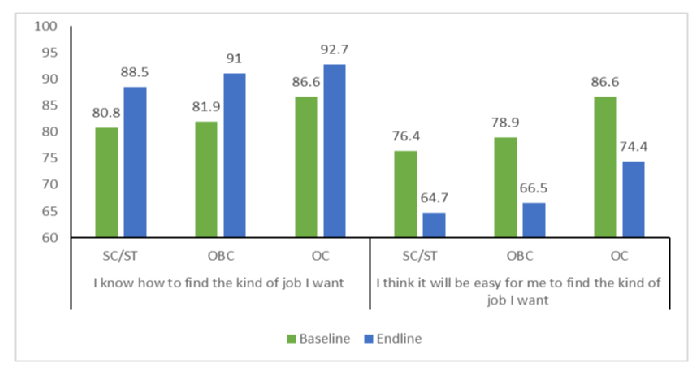

In line with the above findings, we find that lower proportions of SC/ST participants at the baseline reported that they knew how to find the kind of job they wanted (Figure 3). Although all groups increased their knowledge, which is likely to be related to their development of job-specific skills over the course of the training programme, still by the endline a lower proportion of the SC/ST group (88.5%) than the other two groups (91% and 92.7%) were confident of finding the kind of job they wanted. Despite this increased knowledge of how to find a job, Figure 3 also shows participants’ views of their ability to find the job they want: over three quarters of participants in all groups said that they thought it would be easy at the baseline, whereas only 64.7% of SC/ST groups (compared with 74.4% of OC participants) thought so at the endline. There is clearly a need for more research to assess the impact on job outcomes post-Covid.

Figure 3: I know how to find the kind of job I want; I think it will be easy for me to find the kind of job I want (%)

The acquisition of soft skills: a longer-term outcome?

Although previous researchers have measured the impact on labour market outcomes of cognitive or hard skills, and their relationship with non-cognitive skills (within which soft skills are included), the data tends to come from western countries, with little information from developing countries (but see Buhler et al, 2020). Although different measures are used, findings overall tend to show that non-cognitive skills are at least as important as cognitive skills in future earnings and employment success, with some research showing that this is especially important for those from more disadvantaged groups (Brunello and Schlotter, 2011; Heckman et al., 2006). Laajaj et al. (2019) hypothesise that non-cognitive skills are even more important than cognitive skills for labour market outcomes in developing countries.

Our data shows that caste is an important factor in assessing skills gain in India. We have already highlighted in other analysis of the same data that SC/ST participants have significantly lower income aspiration than other castes and that female participants have significantly lower aspiration than their male counterparts (Sarkar et al., 2021). Aspiration gaps exist even after controlling for various background characteristics. Here, we find that participants from the most disadvantaged caste groups began the programme with lower levels of self-reported soft skills overall but, over the course of the training, they succeeded in reaching similar levels of soft skills as participants from higher caste groups 6. The findings are much in line with Ibarraran et al. (2014) and Acevedo et al. (2017) in the Dominican Republic and Cho et al. (2013) in Malawi, where skills training programmes had positive effects on trainees’ perceptions of self-esteem, future expectation and well-being. However, how such skills gains may be translated into positive employment outcomes is less clear at the current time. Covid and the lockdown had clearly affected both the confidence of our training participants in their future job prospects and the availability of jobs. Even in this, though, there was some evidence of a differential impact by caste which suggests that, despite their skills gains, young people from lower caste groups anticipate greater difficulties in labour market integration.

Our data shows that caste is an important factor in assessing skills gain in India. We have already highlighted in other analysis of the same data that SC/ST participants have significantly lower income aspiration than other castes and that female participants have significantly lower aspiration than their male counterparts (Sarkar et al., 2021). Aspiration gaps exist even after controlling for various background characteristics. Here, we find that participants from the most disadvantaged caste groups began the programme with lower levels of self-reported soft skills overall but, over the course of the training, they succeeded in reaching similar levels of soft skills as participants from higher caste groups 6. The findings are much in line with Ibarraran et al. (2014) and Acevedo et al. (2017) in the Dominican Republic and Cho et al. (2013) in Malawi, where skills training programmes had positive effects on trainees’ perceptions of self-esteem, future expectation and well-being. However, how such skills gains may be translated into positive employment outcomes is less clear at the current time. Covid and the lockdown had clearly affected both the confidence of our training participants in their future job prospects and the availability of jobs. Even in this, though, there was some evidence of a differential impact by caste which suggests that, despite their skills gains, young people from lower caste groups anticipate greater difficulties in labour market integration.

It is difficult to know how successful these young people will be in negotiating the labour market as lockdown restrictions are loosened, and whether or not caste differences will persist over the longer term, but we can say with some confidence that a relatively short-term skills training programme has demonstrated significant gains in soft skills development among the most disadvantaged young people.

___________________

1 The average duration of classroom training was just over 3 months (103 days). The average age of our baseline sample was 19.8 and 58% of the sample were female.

2 Below Poverty Line’ (BPL) is an economic measure used by the government of India to identify individuals and households in need of government assistance. In India, scoring is done on 13 parameters ranging from 0-4. Families with a score of 17 or less out of 52 marks are classified as BPL.

3 Participants could answer ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ to all questions. Here we combine the strongly agree/agree categories into ‘agree’ (the % reported above) and disagree/strongly disagree’ into ‘disagree’.

4 Another series of questions in the endline survey did gauge the impact of Covid (not reported here).

5 A series of interviews with participants also showed that the majority of participants were worried about the financial impacts of not working. The endline survey also showed that household income fell from Rs. 1721 per week in pre-lockdown to Rs. 632 per week during the endline data collection.

6 There were also some differences by gender which are not reported here. For more information on gender differences, see: Sarkar et al. (2021)